MATTERS OF OBSESSION

The painful feeling that connects us: artist Penny Siopis on the empathetic potential of shame and vulnerability

The collective and the individual, the personal and the political, and the terrifying ambiguity of vulnerability were all brought to the fore in Penny Siopis’ exhibition Three Essays on Shame, in the Freud Museum, London, and in her new film, Shadow Shame Again.

The word “shame” is defined in the Merriam-Webster dictionary as “a painful emotion caused by consciousness of guilt, shortcoming or impropriety” or, “a condition of humiliation, disgrace or disrepute”. The South African use of the word, however, holds this connotation as well as another, unique meaning. “Shame man, poor guy,” one might exclaim, when hearing some bad news about a friend or relative. It’s the equivalent of saying “I feel for you”, a heartfelt expression of empathy for someone else’s embarrassment or hard times. Further, the Afrikaans word for shame is “siestog”, which also has a dual meaning, “sies” being a colloquialism of disgust, and “tog” of affection.

“You have the putting together of opposite feelings in one word,” contemporary artist Penny Siopis explains. “It embodies a moment of empathy or affection, but it can also be disgust, or distress, and you’re not only disgusted with something wrong out there, it’s you, yourself that feels wrong.” Interestingly, this double-sided version of shame might be unique to South African vernacular, and, as Siopis points out, “Popular language holds a lot of very complex things.” The particularities of colloquial language can provide valuable insight into cultural realities.

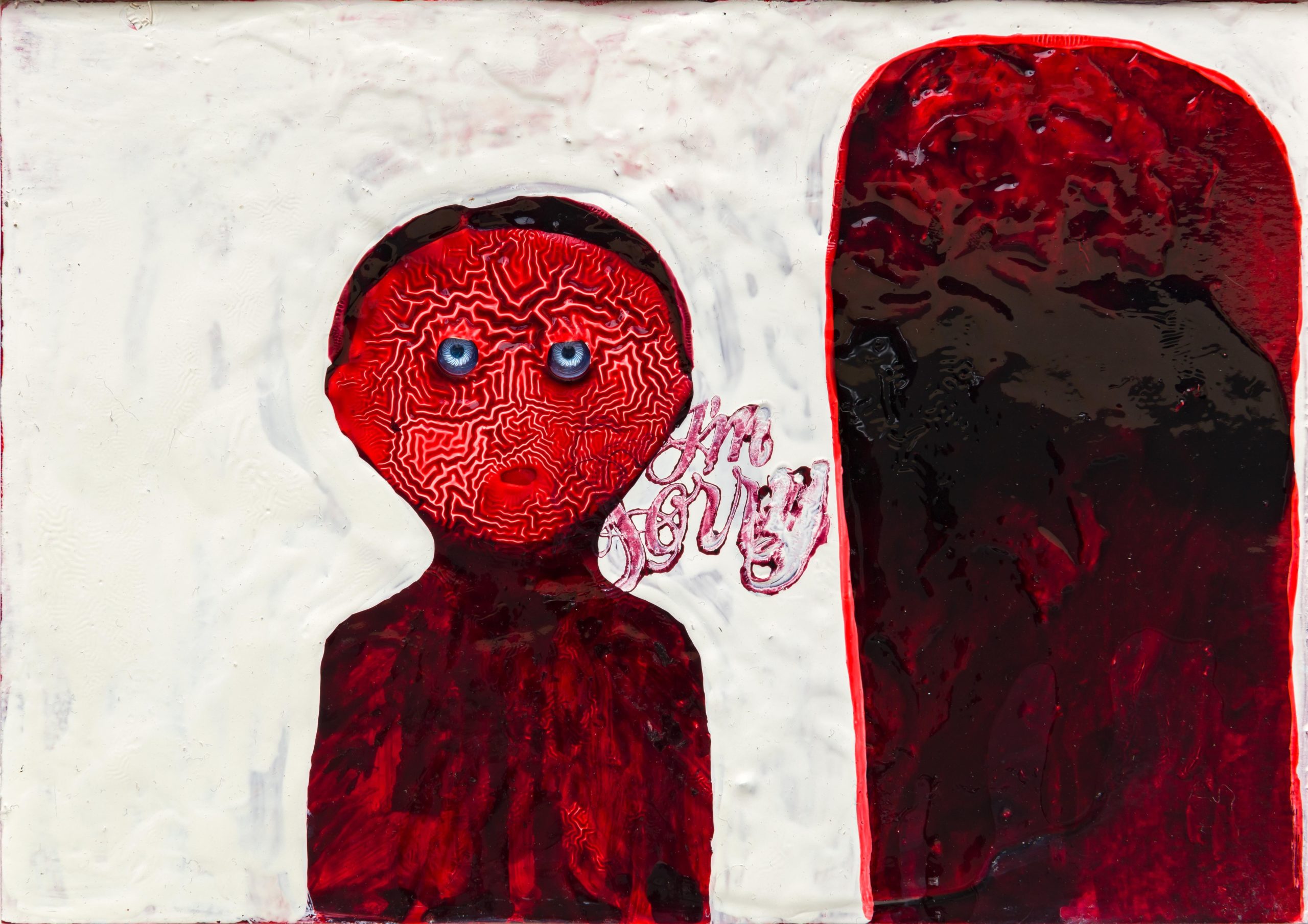

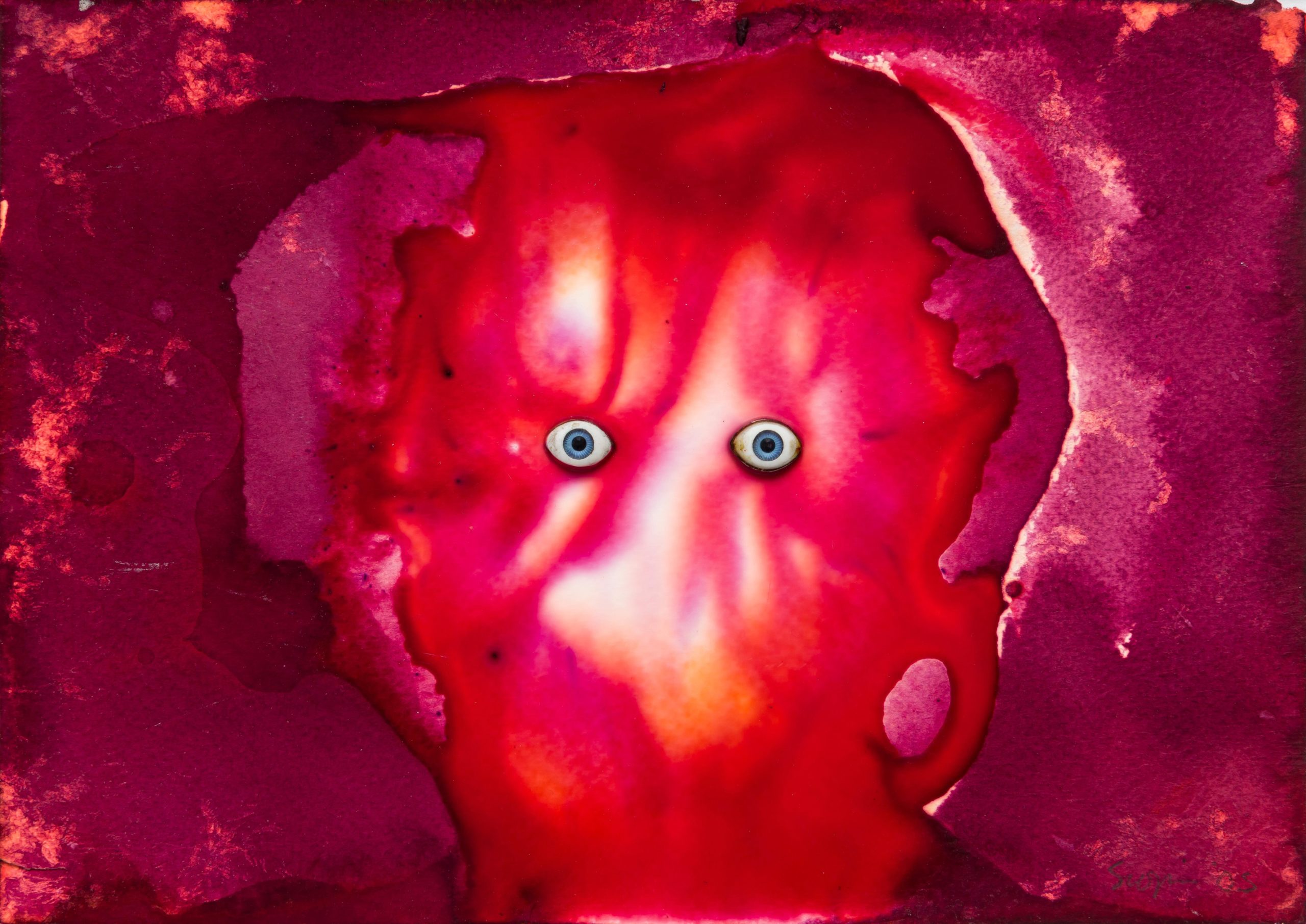

Shame installation at Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town. © Penny Siopis. Courtesy Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg. Photo: Mario Todeschini

Siopis, a South African artist working in Cape Town, but born in Vryburg, Northern Cape, in the 1950s, has materialised the emotion in her iconic series of paintings titled Shame, currently on view at the Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town, and, in 2005, hung in the Freud Museum, London, in an exhibition titled Three Essays on Shame.

Over a decade later, she broached the topic once more in her recent film Shadow Shame Again, finished just this year. For Siopis, these works are part of a more expansive realm of thinking that she calls the “poetics of vulnerability”.

Being vulnerable, Siopis explains, “has to do with the relationship between an individual and a community”. When one feels vulnerable, one feels over-exposed, or under scrutiny by those around them. On the opposite side of the spectrum, feeling vulnerable might cause a person to close themselves off from the world completely, in order to escape that exposure.

Shame installation at Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town. © Penny Siopis. Courtesy Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg. Photo: Mario Todeschini

Working in the “poetics of vulnerability” Siopis attempts to materialise the feeling; the word poetics “speaks to the realm of imagination”, which is important because “feelings and senses of vulnerability can’t really be depicted literally, but can be expressed in other ways”. It is near impossible to paint a lifelike image of a vulnerable person because feeling vulnerable is a turmoil that happens within us. The conceptual works that Siopis creates are abstract and haunting. Or, as she referred to her paintings in a 2016 Frieze London catalogue, “carnal documents” that pluck at our unconscious knowledge.

To Siopis, the emotional state of shame is “an image of vulnerability”, and just like the dual meaning of the word in a South African context, shame is double-sided in its effects. “It can be a very negative toxic thing, or, if you acknowledge the vulnerability, take it on, it can be fertile ground for empathy.”

We have all known shame in our lives. In small ways, like falling over in front of a crowd of people or being belittled by someone at a party, but perhaps also in bigger ways that are more violent and linger painfully, constantly grating. It’s almost a guarantee that every living human being has had a time in their life where they have experienced the visceral, cringing ugliness of shame.

Shame installation at Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town. © Penny Siopis. Courtesy Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg. Photo: Mario Todeschini

For this reason, it is something that all of us can understand, a connecting factor. The vulnerability that shame insinuates, says Siopis, is a “form of acknowledging relationality rather than sealing oneself off, and being for the self only”. The work that she does regarding shame is “open form” or “something that is not closed in its visual shape, not contained completely, being rather a bit frayed at the edges”. And because of this her work becomes a “visual opportunity to connect… almost a medium for a person to express themselves even to themselves… an opportunity to lend an occasion to a person’s own imagination.” Her work could connect to“many, many things; many, many different people’s experiences”.

Could shame be a ground for empathy? In a Zoom conversation on 25 March, that took place as part of Art Basel’s OVR: Pioneers talks programme, with art historian Griselda Pollock, and mediated by Stevenson Gallery’s associate director, Sinazo Chiya, Pollock referenced the “piercing” nature of shame. It passes through your skin and into your insides; it makes holes.

Shame installation at Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town. © Penny Siopis. Courtesy Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg. Photo: Mario Todeschini

This resonates with Siopis’ thinking on the topic. “Earlier on I looked at this idea that the individual is sort of bound by the skin on their body, the skin as a kind of boundary. But the skin is porous, and receptive to the social and political world. One can talk about being thin-skinned when you’re too sensitive, or thick-skinned when you’re too remote.”

There are a million little learned habits, memories, inherited opinions that make us who we are. “You get filled up with other stories about yourself,” Siopis relates, “this is where I find an interesting relationship between the individual and the group, because there is no way that we’re each signed, sealed and delivered individually. We are a porous world.”

In knowing that we are at once ourselves and part of a larger whole, that each person has their own individual experience of the world, but an experience that is moulded and shaped by others, perhaps we can be more understanding of one another. Shame, while universally felt, Siopis writes in an exhibition description “has neither a single face, nor a common language”. It can be felt individually as well as communally. Let us not forget the communal shame that continues to haunt us, as South Africans (and perhaps even the rest of the world) – the lasting effects of the violence that was apartheid.

Shame installation at Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town. © Penny Siopis. Courtesy Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg. Photo: Mario Todeschini

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) established in 1995 to investigate the gross human rights violations that took place under the apartheid regime, in its attempt to collect and record painful testimonies by South Africans from a wide variety of social backgrounds, was, in a way, publicising multiple different experiences of shame. Dullah Omar, the former minister of justice, called the TRC a “necessary exercise to enable South Africans to come to terms with their past on a morally accepted basis and to advance the cause of reconciliation”. Pain was spoken and witnessed by the public partly as a means of allowing the shattered South African population to understand one another better, perhaps to empathise.

Siopis points out that the TRC was also “a psychological inquiry”, it was asking questions like, “What makes people do this? How was it that the state could be so brutal? How could people be so brutal?”

Shame installation at Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town. © Penny Siopis. Courtesy Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg. Photo: Mario Todeschini

Shame installation at Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town. © Penny Siopis. Courtesy Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg. Photo: Mario Todeschini

For this reason, the TRC, its mission and its procedures, became a central part of Siopis’ thinking when putting together Three Essays on Shame, held in the Freud Museum, London, in 2005.

The museum, once the final home of Sigmund Freud before he died of cancer, holds significant connotative power. Freud, being the father of psychoanalysis, pioneered the idea that inner psychic turmoil and childhood trauma could be the underlying causes for abnormality, perversity, or psychological breaks (ie, madness) in an individual, and unlocking these unconscious blocks could be a potential cure.

While psychoanalytical practices are no longer the only practice used in mainstream mental health realms, Freud’s thinking changed the world’s understanding of the unconscious. It became apparent that we have thoughts/dreams/reactions in our brains that are hidden, that we do not experience consciously, but that still have significant sway on our day-to-day lives and decisions. Siopis asserts that, “Freud opened up a huge space for thinking about the way that the psychic space is also a social space. You know, you bare out your social anxieties in your psychic way.”

Shame installation at Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town. © Penny Siopis. Courtesy Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg. Photo: Mario Todeschini

Shame installation at Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town. © Penny Siopis. Courtesy Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg. Photo: Mario Todeschini

Marking the centenary of one of Freud’s most boundary breaking books, Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, Siopis’ 2005 exhibition Three Essays on Shame put a traumatic and collective South African experience into conversation with Freud’s groundbreaking theoretical framework.

The installation was split into three sections in three different rooms of the museum: the family room (gesture), the bedroom (unconscious), and, of course, the famous consulting room (voice).

In the latter space, containing Freud’s emblematic consulting couch on which his patients used to recline as he psychoanalysed them, Siopis played voice recordings of seven South African figures who were involved in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). Each spoke of their respective relationships to the commission, as well as their individual experiences with the shame that the process brought to the fore. These voices included Antjie Krog, an Afrikaans journalist who reported on the TRC, and who spoke of the shame that she held for her “group”, the Afrikaaners, marked as perpetrators; Edwin Cameron, a gay rights activist and judge in the TRC, who referred to the shame he felt over being queer and HIV-positive in an apartheid setting, and Pumla Gobodo-Madizikela, who related a tragic story about an older black woman raped by a group of young white men, one of many horrifying stories about racialised violence against women during apartheid.

These recordings, while not visual, are still a substantial occupation of the space. Siopis talks of the materiality of recordings: each voice has an accent, a place, and a time in which it was made. Not only is the content of the voice recorded, but the “ums and ers”, the emotional register, the contextual evidence that humanises these individuals is present. It’s almost as if the owners of the voices are being psychoanalysed by Freud himself, right then and there.

Further, as Siopis points out, the iconic room is “filled with these voices, which makes you realise as you’re looking [at the room] that you’re also imagining. You’re not seeing a pictorial rendition of [the testifier’s] shame, you’re imagining it through their voices.”

Shame installation at Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town. © Penny Siopis. Courtesy Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg. Photo: Mario Todeschini

Shame installation at Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town. © Penny Siopis. Courtesy Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg. Photo: Mario Todeschini

In doing the mental work it takes to picture and understand someone else’s shame, one is perhaps, and hopefully, empathising with the other in a moment of vulnerability. It’s a further nod to the work of the TRC, which recorded hundreds of hours of testimonies, archived, and published them for all to hear – South Africa, as a whole, became vulnerable and ready for a change.

To Siopis, the house of Freud as a whole was a space of vulnerability. It was where he began to recollect himself after escaping Nazi Vienna, where his body started to collapse under the pressure of terminal cancer, and, eventually, where he died.

In his bedroom, where Freud dreamt, loved, and died – arguably the centre of his vulnerability – Siopis placed the frieze of her shame paintings. Framing the literal death-bed of Freud, the shame paintings, each a unique and abstracted visual of shame, came together to create a sea of voices, a collective shame.

In forcing us to recognise the expansiveness of shame; the very humanness of it, Siopis reminds us that human vulnerability can transcend national borders and colonial hierarchies. The work of the TRC, as well as the voices of shamed South Africans, are valid in the house of the father of psychoanalysis, a keystone figure in the Western canon. Siopis is expanding the canon, she is making South African voices relevant within a global context, as they should be.

At the same time, in using fragments (individual tiny paintings each with their own narrative) to create a collective (the grid of paintings making up the frieze), Siopis brings us back to the idea that there are always holes in a collective; stories that are missing, or forgotten, or downright silences. Even in the TRC’s expansive archive, many voices were not heard.

“What art does,” she explains, “or at least what I am interested in doing is making these holes and gaps concrete or physical. Not through a depiction of whatever it might be that is silenced or not there, but more by showing that there are holes and gaps. That can literally be through recognising that these are many fragments, which means that there must be stuff between or breaks, in a way. Fragment, by definition, says that it’s only one little part, so you think, where are all the other parts?” Siopis allows us to feel that there are gaps, not necessarily fill them.

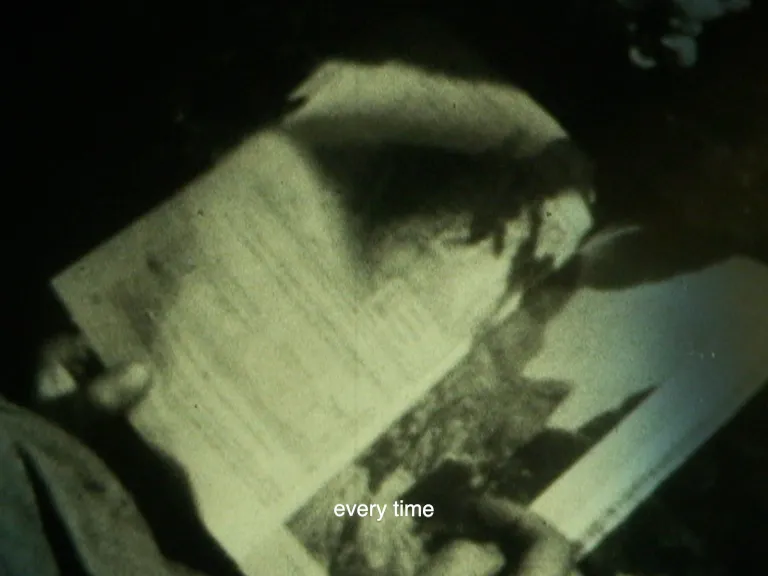

“Shadow Shame Again”. Still from Shadow Shame Again. © Penny Siopis. Courtesy Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg.

Fragments and the spaces between things are particularly present in Shadow Shame Again, Siopis’ 2021 film that tackles the endlessly shameful and achingly prevalent topic of gender-based violence. Majorly a compilation of home videos made on old super 8 film cameras that Siopis found in vintage and secondhand stores (and some filmed by her own mother), Shadow Shame Again displays the physicality of the celluloid film, as well as the content captured on it. The celluloid “is scratched and ruptured over time, and then it’s put through a method of transferring it onto digital, and that method actually records all the scratches and dust points. It’s like recording through other means the various gaps and holes that can’t actually be visualised. These gaps can also suggest things that are unspeakable or difficult to show. They make them present, rather than not.”

In the case of this film, the story is one of exceedingly difficult and unspeakable violence. Dedicated to Tshegofatso Pule – seven months pregnant, stabbed to death, and found hanging from a tree in Roodepoort’s Durban Deep on 5 June 2020 (the heart of lockdown) – Shadow Shame Again addresses what Siopis, referencing President Cyril Rhamaposa, calls the “other pandemic” that hangs, dark and heavy (a shadow) over South African society.

Still from Shadow Shame Again. © Penny Siopis. Courtesy Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg.

The story of Pule is horrific, and, as Siopis explains, it also became “a kind of rallying cry, a call to protest that was doubly difficult because it happened in a certain time, a pandemic time”. Shadow Shame Again is “not a literal story”, meaning we do not see any images of Pule herself: “in a way, it’s an image of the imagination”. Instead, we watch old clips of other people’s family lives as we imagine the incredible pain, the incredible shame that Pule’s violent and untimely death brought upon the victim, her loved ones, and the nation. “A locus of national shame,” says the subtitle, at the end of the film.

“The impact of the image explodes into everything,” Siopis says about Pule’s story. We think of lynching, of colonialism, we think of rape, murder, violence. We think of a woman with a child, a woman who is about to bring another life into the world, brutally killed – two birds with one stone.

Still from Shadow Shame Again. © Penny Siopis. Courtesy Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg.

Still from Shadow Shame Again. © Penny Siopis. Courtesy Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg.

Most jarring of all is the pairing of this story with home videos. We watch an empty tree (where is her body?), a child climbing a tree, a baby swinging, a woman walking alone on the beach, a baby’s empty shoes. Another pair of empty shoes. Images that, filmed initially with love and care, are heart-wrenching and terrifying when placed in this new context.

We begin to imagine ourselves, or our loved ones in Pule’s position. Pumla Dineo Gqola, quoted at the onset of the film, says it best: “Survivors of gender-based violence are the world’s majority; they walk the streets all day everywhere, sit next to you in class, they are the person you are busy falling in love with, they are your sister, your best friend, lover, mother, daughter, your teacher.”

Further, it reminds us that the institution of the nuclear family is not a safe space for everyone. Siopis talks of domestic violence, and how within the frame of the Covid-19 pandemic, “Women and children are locked into the domestic and intimate space, and that space that would usually be a space of comfort is now potentially a space of harm.”

This “other pandemic”, as Siopis (and Ramaphosa) refer to gender-based violence, has been plaguing South Africa for far longer than Covid-19. “Even in the idea of ‘other’, is the sense that we are all still focusing on the coronavirus. And it’s entangled with all sorts of global geopolitics, all sorts of things that the globe, in one way or another, finds is a priority… many of the communities involved in these ‘other’ problems are having to constantly push for public attention.”

Siopis linked the issues of gender-based violence to that of racism. A racialised woman’s body is often the site on which power relations are acted out. Both racism and gender-based violence are systemic and global, they are pandemics, and they need attention, as much (perhaps even more so) than Covid-19.

To hark back to Siopis’ Three Essays about Shame – which commented on issues of apartheid and the battle against the shame of racial injustices – these continue to be problems that we face. The TRC clearly did not heal racial tensions nor racial disparity in South Africa. Even those of us who are “born free” understand that the shame of apartheid is still with us. We are still “haunted by something that you were never part of in your actual experience, but your experience as a subject, goes back beyond what you actually, empirically experienced as a body, a physical body. You hear things from your parents, or from the world around you as a little child and it becomes you. Shame becomes you.” Just as Pumla Dineo Gqola’s voice resonates in both Three Essays on Shame and, more than a decade later Shadow Shame Again, we are struggling with different versions of the same problem.

Still from Shadow Shame Again. © Penny Siopis. Courtesy Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg.

Still from Shadow Shame Again. © Penny Siopis. Courtesy Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg.

Still from Shadow Shame Again. © Penny Siopis. Courtesy Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg.

So why aren’t racism and gender-based violence getting the attention that they deserve? Why are these issues not placed front and centre so that we can work to solve them once and for all? Perhaps because they are problems of the system, and, as Audre Lorde once aptly put it, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house”.

Siopis points out that in the case of the Black Lives Matter protests, “it wasn’t an official figure who brought up this issue, it was the people on the streets who were there, who witnessed, who are protesting this, who are bringing this problem to the fore.” Similarly, she was taken with the outcries on social media when Pule’s story came out. It’s the “other forms, not the official forms that are bringing it to public consciousness. There is something interesting about the collective in that in itself.”

In fact, the backing sound to Shadow Shame Again, made from solely human voices, is another nod to this collective action. The film starts with whistling and tweeting, then ramps up into a clapping that sounds almost like something burning up in a fire. “It’s from the University of Cape Town choir, they are using their hands to make that particular sound,” Siopis explains. The noise of the clapping accelerates and becomes almost unbearable especially paired with the flashing images of the film, “and we think, can we bear it anymore? And then the singing comes, like a balm.” Human voices heal where human violence has wreaked havoc.

The voice that takes over is that of Mbali Ngube, who posted her rendition of the song Askies I’m Sorry on Twitter in response to the news of Pule’s murder. “I just found it really compelling and was able to contact her. She’s a student at the Nelson Mandela University, an aspiring journalist.”

The song, which sounds like it is sung by a choir of multiple people, was actually made with an app – Ngube layered recordings of herself over one another to create the final product. “Even though she is alone, she’s singing as if she is many people. I thought that was very empowering.” And it speaks to the idea that we are all part of the larger whole, just as the larger whole is a part of us. You cannot be a person without being porous; you cannot be whole without holes.

The world that we are part of (that is a part of us) right now is a terrifying and uncertain place, a place of unanswered questions and ambiguity. Siopis puts it like this: “The very categories of our thoughts are now being made vulnerable, and that means that the uncertainty that has now produced conditions for this metaphorical vulnerability can also be a space for thinking in a new system. A space for learning should be a space of vulnerability.”

In the midst of all of these moments of vulnerability – the Covid-19 pandemic, the gender-based violence pandemic, the police brutality pandemic, the racism pandemic, and all the other pandemics that might be under appreciated right now – empathy is of utmost importance. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.