KAROO DREAMING

In the darkness, stars step to centre stage

The stars unlock doors to memories in their little cubby holes in the mind, stored there until a smell, a sight, a word, a thought, suddenly frees it.

The author supports Isabelo, chef Margot Janse’s charity which feeds school children every day. Please support them here,

The day is for the night. The long earned fire. The rest of the weary bones. The ache of the wrist released from the steering wheel after driving all day. The left turn into the grounds of the self-catering place you’ve booked somewhere in the Klein Karoo. This looks nice. The welcome by the couple once from Joburg and who spent years in Dubai then felt the yearning for the Big Sky and the Klein Karoo. Housemartin. Odd name; after the bird, I suppose. First time we’ve stayed in De Rust. Pity about Covid, we need to avoid those plumed restaurants and that crazy pub over there. Need to find the room and the braai they said they had.

Gestewel & Gespoor, De Rust. (Photo: Tony Jackman)

Some enamel soup bowls from their little shop, Gestewel & Gespoor. Booted and suited. It has a subtitle. Jan Venter en die ma van sy kinders se winkel. Somebody around here has character. There’s going to be load shedding, the lady tells us. We’ll bring you a light. Much later the man brings the light to the dark braai under the spreading palm between the gravel yard and the row of little cottages which are empty except ours in the middle. I’m happy under my stars with my whisky in the jar. We’ve eaten the springbok loin and the foiled potatoes and I’m the last braai man standing. I thank the man courteously but when he’s gone I turn the light off and slink back into the night.

The dry eye is soon moistened by the jar or two near the porch of the self-catering cottage where earlier the braai fire was tamed to coals and the potato turned soft and crunchy in its foil sarcophagus, the bloody meat of the springbok loin you bought in Graaff-Reinet rendered desirable by the fire. The drive-tensed muscles eased by a whiskey or three.

With the lights out in De Rust, the stars step to centre stage. Where have you been, my lovelies, while we trudged in our blighted electric drabness, hiding in your celestial lair, out of sight but not mind, because the soul always yearns for you and the wonder you bring. Just by being there, twinkly and unknowable. The power of the power outage is that it brings the majesty of the night. Usually I complain, but tonight I’m in no hurry for the lights to come back on.

The starscape unlocks the doors to recesses not thought of for a while, memories in their little cubby holes in the mind, stored there until a smell, a sight, a word, a thought, suddenly frees it, and off you go to the place long forgotten. To your feet in smaller shoes, the Cortina GT your dad drove, the off-white one with the red stripe gashing its side, turning off the highway into Citrusdal and parking outside the hotel.

The childhood smalltown hotel bedroom. The basin in the corner with the little toothbrush and -paste holder. Push-button radio on the wall next to the bedstead, Springbok Radio, English service, Afrikaans service, Tannie Esme Euvrard and Hospitaaltyd. Daar’s ’n lied en ’n glimlag vir jou… The creaking Oregon floor. The mahogany bedstead and massive mattress on which the boy lies and stares at the ornate high ceiling, thinking of ghosts. Candle by the bedside, Gideon’s Bible in the drawer. Birds’ claws scuffling on the roof, he hopes, and is that a crone’s cold bony finger dragging across his forearm or just his fear of the night? The tokoloshe. Dare he look under the bed? The knock on the door, the boy starts, arms a-shiver, wide-eyed. Opening the door, a blue tunic-clad steward with a tray holding a glass with ice in it and a small bottle of Coke. The dinner gong will be in fifteen minutes, he says.

My braai spot in De Rust, before the lights went out. (Photo: Tony Jackman)

In De Rust, the braai coals have turned cold. But you’re far away from here. The stars seem to float and rearrange themselves into the Milky Way above Sutherland, reached by snaking through the Verlatenkloof Pass, the Pass of Desolation. The boy-now-man would check the temperature gauge as he entered the pass from the Matjiesfontein side he’d left 90 km earlier. If it measured 10° at the bottom of Verlatenkloof, by the time the little turquoise Opel exited the grey, moon-like plain that leads into Sutherland it would register 0°. But nowhere gives you stars like Sutherland does on a clear night. I’ve seen the stars above Calvinia and Cradock, Hanover and Prince Albert, and thrilling though they are, the stars over Sutherland are matchless. You can see forever, see the universe, see your past, see your future, see the unknown and the unknowable. See what’s hidden in your dreams; see everything you’d forgotten. See yourself in the postage stamp garden in the Georgian house in Cavendish Street, Chichester, finally getting usable coals in the Meccano metal braai that had taken all afternoon to assemble, following the mangled instructions on the box. And the Tesco charcoal pack that smoked more than flamed, and the sad little try-for-braai that followed. You’d turn the house lights off and stand in the little yard with the silent cherub at the end and the ancient stone walls between you and the neighbours on either side, and look up. And nothing. Nothing. And you’d know: you had to get back, you had to go home.

In Sutherland, only months later, you’d follow Dave O’Hearns’ laser making its patterns between the stars, expertly turning the night sky into constellations and stories of how they all work together, and wonder how you ever imagined you could have lived in the land of your ancestors for more than a year or two, with grey where stars should be. You’d drift back into the kitchen and put the lights back on and the tungsten would seem unnatural, out of place, yellow where it had seemed white before, the brightness now an affront. But you’d serve their desserts to the customers who’d taken a respite from their food to consume the stars and wander off into universes unknown, just for half an hour; then back to the brandy pudding, the peppermint crisp tart.

In De Rust, the forgotten lights appear rudely, unannounced, an unwanted guest hurling you back into the present, like it or not. Power is restored, the universe vanquished. But you need to sleep anyway, for tomorrow’s drive is longer than today’s, to Arniston, the old family haunt brimful of salty, sandy memories, and you turn in, lights out.

Footprints in the sand follow a memory running into the sea. The eyes watching it connect to a memory of a little boy and girl playing on the beach. For the girl, now a woman in middle age, it is her most treasured photo of her brother long gone. For the watching eyes the footprints disconnect from the boy, who would now be in middle age, and reconnect to the grandson, the nephew he would never know, playing in the sand on the beach, right there, before the watchful eyes. Niccy running arms akimbo into the waves and disappearing, then an arm shooting out of the water and flailing, his mother racing in after him to pull him out. The day the boy might have drowned but who would die young anyway. And the GrandBoy now, sweet and innocent, playing with his bucket and spade on the beach; yet to become old enough to know what once happened, right there, and what was to come.

Roman Beach photographed from our rented house. (Photo: Tony Jackman)

We stayed in Roman View with its view of Roman Beach two decades ago, lured by its eyrie position that we’d enjoyed several times before. The place has been “done” in the meantime but we’re all feeling blessed and thoughtful because each one of us has memories, except for the GrandBoy who is here to start making them.

We were introduced to the seaside village also known as Waenhuiskrans in 1979, but as Arniston, and the name stuck for us. We stayed in Ben Viljoen’s wooden cabin on the beach and probably ate kreef and mussels. To get there in those days from Cape Town meant driving on a dirt track through a series of coastal farms, opening and closing three or four cattle gates, and finally emerging near Bredasdorp for the 20km trek to Arniston. There was the hotel, then a quarter of its present size, the untouched (as yet) fishing village called Kassiesbaai, and a score or two of simple single-storey houses. Nothing too fancy.

Then the people with too much money came in and corrupted the core of the town by spending too much on too-big houses made of too many oversized stones, too little thought for the feel of the place, and built high, too high. My son-in-law and I stood on a sandy promontory and peered at the arrogant horror of a three-storey monstrosity built at the edge of a minor cliff, shaking our heads sadly, at their blocking of the view of whoever owned the two-storey (itself too much) house behind it.

In their greed they destroy charm and character; their avarice begets ugliness.

All we want here is family and remembering, and making new memories to return to one day. We were here before our daughter was born; she has known it all her life. And now the GrandBoy is here for the first time, not quite two and a half, too young yet to know what the place means to his parents, his grandparents, too young yet to be told about Niccy and shown the photos of him and Jess on that beach, right there; he was your uncle. And have me tell him about the time we were here with Keith, and who he was. And John-John and who he was, and show him photos. Of Drin and I collecting mussels from those rocks, right there, and making an illegal fire on the beach, and me putting them in a big pot and cooking them too long in wine and onion and herbs, and them shrivelling to almost nothing, and Drin chuckling and shaking his head. And how Drin left long ago for England, soon after we did, but unlike us never returned, and is now ill, so ill, and cannot leave his bed, and my heart longs to fly there and visit him but that’s impossible right now. And how I wish he could come back here and see the Big Sky and the endless stars and have us hug him and look him in the eye so he can see how loved he is. Maybe we’ll send Drin pictures of the GrandBoy on the beach to distract him from the ceiling beyond which there are no stars, and Greater London where no fires are allowed.

Braai with a view. (Photo: Tony Jackman)

All who had once been with us in Arniston are there with us in the things we remember and the stories we tell at the table or around the braai. The cherished weekend, the first time any of us had been there in so many years that none of us could remember, flies by in breakfasts and walks and braais and suppers at the long table in the picture-window lounge. My two-lamb-neck supper cooked in the potjie they’d brought because mine’s too small. My make-do potato, sweetcorn and chakalaka bake to go with Neal’s inevitable steaks, but without his own world-famous rub this time, because he’d discovered Funky Ouma’s African Rub, which gives a similar flavour to meat but with less effort and having to keep coriander leaves fresh on a weekend away. When we leave my daughter gives me the rest of the Funky Ouma tin and Neal’s eyes widen as if he’s screaming inside. But ever polite. You’re giving it to your dad? Okay… sure!… no no don’t worry, we’ll get more. Dad doesn’t argue.

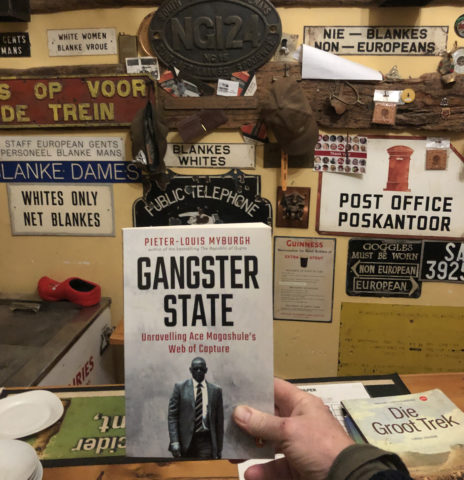

Goodbyes are sweet but hard. Family times together are more precious than ever in these times. But the road takes us until weary bones turn left into The Willow historical guest house in Willowmore, hidden deep in mountains in one of the Karoo’s more obscure valleys. The history here is as dark as a cloudy Karoo night. Net Blankes and Nie-blankes signs jostle with Whites Only and Blanke Dames admonitions behind the bar as if to even things out so that we’re clear that these are not instructions, they’re museum pieces. In the Bad Old Days these signs would never appear in the same place because that would have defeated the object of separating us.

Madiba and friends. (Photo: Tony Jackman)

Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd glares at you from a row of busts along a shelf. Mandela’s bust is next to him but somebody has turned it around to face the wall. I turn it back. I’m as offended as a snowflake at first but then I think about it. Was it an artistic comment? Is he turned away so that he cannot see the relics of what he fought against; the affront to all that is good and right?

An unorthodox bar wall miscellany. (Photo: Tony Jackman)

A green marble statue of the Voortrekker Monument stands on a table next to a pink protea with an even pinker ribbon around it. A boerevrou reprimands you from an oval picture frame. She must have been a fright to have been the child of; the original Tannie Kappie. A framed certificate heralds the founding of the Afrikaner nation. Boer generals stand to attention in another, Hertzog shoulder to shoulder with Kritzinger in the top row, Louis Botha and De la Rey, De la Rey below them. The song plays in my mind for the rest of the night but with Matjiesfontein’s singing tour guide Johnny Theunissen’s lyrics instead. De la Rey, De la Rey, gaan jy vir Zuma kom kry, De la Rey? Eendracht maakt macht, the poster tells us. Unity makes strength. My eyes connect with Mandela’s on the shelf. What say you, sir? Then I turn to the bar counter and on it is an ironic copy of Pieter-Louis Myburgh’s Gangster State, bringing perspective. I wonder what De la Rey would make of that bust over there, and this book.

Irony, photographed. (Photo: Tony Jackman)

At dinner in the chintzy dining room, my heavy silver knife and fork are emblazoned P&O. I picture them being used many times in the dining halls of the great white-hulled passenger liners with their yellow funnels. I choose the Karoo lamb curry, simply but pleasingly made in that way of the old hotel kitchens with their Rajah packets and Mrs H.S. Ball’s.

Dreams that night are peppered with the back of Mandela’s head, Verwoerd’s scary-glary eyes which dissolve into Tannie Kappie’s death stare, and queues of people waiting to be allowed into a segregated store while whites take advantage of their Net Blankes signs.

The night consumes the day. In the Karoo, the day is for the night, the night is for the stars. Out of darkness, light. DM/TGIFood

To enquire about Tony Jackman’s book, foodSTUFF (Human & Rousseau) please email him at [email protected]

Our Thank God It’s Food newsletter is sent to subscribers every Friday at 6pm, and published on the TGIFood platform on Daily Maverick. It’s all about great reads on the themes of food and life. Subscribe here.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Ai, te lekker. Such lovely journeys and memories of the Karoo. Dankie Tony.

Thank you John

So evocative. Thanks for the journey. Such a good read.

Sutherland just climbed onto my bucket list…..