Almost every week, South Africans wake up to reports of yet another outbreak of taxi violence, especially in Cape Town. Routes are closed, commuters are stranded, and families are left to mourn lives senselessly lost.

What should be a routine system of public transport has too often become a source of danger. The minibus taxi industry, long regarded as the backbone of our public transport network, finds itself trapped in a painful impasse where violence has become both the symptom and the cause of its ongoing crisis.

It must be said without hesitation: this cannot continue. The industry that transports the majority of South Africans daily, especially the working poor, is tearing itself apart.

The violence is not only killing people; it is destroying the very spirit that once made the taxi industry a symbol of resilience and self-determination.

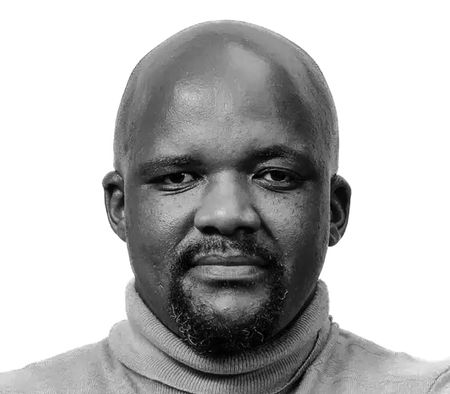

As someone who has spent years researching and engaging with taxi operators, commuters and associations, I write this as an academic and a concerned citizen: the violence must stop. For the sake of commuters, operators and the nation’s economic stability, we must end this destructive cycle before it consumes us all.

The taxi industry’s roots are grounded in survival and resistance. During apartheid, when the state failed to provide adequate transport for black South Africans, communities built their own. It was an act of defiance and self-reliance — informal, flexible and efficient.

Operators pooled limited resources to buy vehicles, form associations and connect townships to the economic centres that excluded them. These early pioneers built not only an industry, but a movement. Taxi ranks became more than just transport nodes: they were spaces of exchange, opportunity and solidarity.

However, as the industry expanded, competition intensified. Routes became valuable assets, and in the absence of effective regulation and dispute resolution, violence emerged as a mechanism of control.

What began as a symbol of empowerment gradually transformed into a battleground. By the mid-1990s, the term “taxi wars” had become synonymous with bloodshed. Today, three decades into democracy, this pattern persists.

In Cape Town, violence erupts with alarming regularity, where disputes over routes and ranks turn deadly. Despite repeated mediation attempts and police interventions, the conflict endures, exposing the failure of governance and leadership.

Unending paradox

The result is an industry caught in contradiction — one that sustains livelihoods while simultaneously destroying them. This is the continued aporia of taxi violence: an unending paradox between survival and self-destruction.

Taxi violence is not an abstract policy debate; it is a lived reality for millions of South Africans. Every gunshot at a rank reverberates across homes, workplaces and schools. Every time a route is suspended, commuters are stranded, losing wages or missing school.

In Cape Town, these disruptions have become almost predictable. When tensions rise, commuters seek alternative, often more expensive, means of transport. Parents fear for their children’s safety. Informal traders lose their daily income. The economic and psychological costs are immeasurable, especially for those already living on the margins.

The violence corrodes public trust. For decades, operators have fought to be recognised as legitimate businesspeople, providing a vital service where the state has failed.

Yet, every new episode of bloodshed undoes years of progress. The public perception hardens; taxi drivers are seen not as transport providers, but as aggressors. The many law-abiding operators who work with integrity are unfairly stigmatised, and the entire sector is tarred by association.

This erosion of public legitimacy may well be the industry’s greatest long-term threat. The continued aporia of taxi violence stems from a combination of social, economic and institutional contradictions. The industry is both a product of exclusion and a vehicle for empowerment.

Taxi operators are not villains; they are entrepreneurs navigating an unforgiving economic landscape. Fuel prices, maintenance costs and debt repayments consume much of their income. Many operate under extreme financial pressure, caught between the demands of associations, financiers and commuters.

In such a volatile environment, violence can become a misguided form of regulation — a desperate attempt to protect one’s livelihood.

Yet it is crucial to recognise that violence is not inevitable. It is a learned response, not an unavoidable outcome. The absence of effective regulation and the weakness of state oversight create the conditions for conflict, but they do not justify it.

The violence continues because leadership — both within the industry and in government — has failed to intervene decisively and strategically.

Economic costs

Beyond its human toll, taxi violence carries enormous economic costs. Each conflict disrupts transport routes, damages vehicles and slows productivity. Workers are late or absent, students miss classes, and the informal economy stalls.

For operators, the costs are direct: lost income, higher insurance premiums and legal fees. Banks and financiers become reluctant to lend, stalling fleet renewal and safety improvements. Government partnerships suffer as trust erodes.

Violence, in truth, is not a show of strength but an act of economic self-sabotage. A peaceful and professional taxi industry would benefit everyone — operators, commuters and the state alike. Peace is not just a moral imperative; it is a business necessity.

The persistence of violence also reflects a glaring failure of governance. For too long, the government has treated taxi violence as a recurring emergency rather than a structural problem. The police are deployed after shootings; permits are suspended; task teams are formed.

But these measures are temporary and reactive. What South Africa urgently needs is a comprehensive national strategy to end taxi violence, grounded in prevention, not punishment.

Such a strategy should begin with permanent conflict-resolution structures — independent mediation and arbitration bodies mandated to address disputes swiftly, before they escalate.

Transparent route regulation is also critical: a modern digital system for route registration, licensing and monitoring would reduce ambiguity and prevent territorial disputes.

Law enforcement, too, must act decisively and consistently against perpetrators of violence, regardless of association or political connections. Impunity is the fuel of this crisis.

Formalisation and economic support should be central to the government’s response. Operators must be given real pathways into cooperative or company structures that enable access to finance, training and subsidies — similar to what is available in other public transport sectors.

Violence thrives where livelihoods are precarious and regulation is weak; economic security and fairness can help replace fear with stability.

Reform from within

Yet, the government cannot act alone. Taxi associations must take responsibility for reform from within. They must move beyond rhetoric and adopt genuine codes of conduct, enforce internal discipline and commit publicly to non-violence. Leadership must mean more than authority; it must mean accountability. Each act of violence diminishes the collective strength of the taxi fraternity.

The older generation of operators, who built this industry through resilience and unity, must pass down those values rather than the legacy of conflict.

The younger generation must define success not through domination, but through professionalism, service and peace. Commuters and civil society, too, have a vital role to play. They are not passive bystanders but the heartbeat of the industry. Without them, there is no business.

Public pressure must demand accountability — not only from the government but from associations themselves. Taxi violence thrives in normalisation and silence; it ends when communities refuse to accept it as inevitable.

A culture of peace is not built overnight. It must be cultivated through shared commitment, public education and daily practice.

Imagine a Cape Town where commuters enter taxis with confidence rather than fear; where ranks are orderly and safe; where disputes are resolved through dialogue, not gunfire. This vision is not naïve — it is necessary. It is the future we must choose.

The minibus taxi industry now stands at a crossroads. One path leads to endless cycles of conflict, death and decline. The other leads to renewal, dignity and prosperity.

The choice lies with those who make the industry move — the drivers, the association leaders and the policymakers. We must remember why this industry was born: to serve, to uplift, to connect. Violence is not heritage; it is a betrayal of that founding spirit.

To the operators and leaders who have built this industry: you have nothing to gain from the blood of your colleagues, and everything to gain from peace. Your power does not lie in the trigger, but in the steering wheel — in your ability to drive this nation forward.

The future of public transport, and the wellbeing of millions, depend on your courage to end the cycle. The continued aporia of taxi violence must end, and the time for peace is now. DM