When Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden was established in 1913, “it was envisioned as a site that served white citizens”. Though still providing limited access to the majority of South Africans, in recent years its potential has widened.

It has gradually been evolving into a place that has offered the opportunity to serve as a repository for onsite learning and appreciation of our natural heritage.

This has occurred through various means: its educational programmes and guided walks for school children and adults; its relatively inexpensive membership system and its discounts for the elderly. These are moves in the right direction.

Given our country’s socio-political history, Kirstenbosch is an important site of people development and job creation, and its natural and botanical wonders should be accessible to all.

It is our strong opinion that this praiseworthy and socially responsible role should be the basis for its future development as an asset to its city, its country and continent, and the whole world.

However, in the past year, in a move reminiscent of our dreadful past, the garden has once more become a resource for elite local visitors and tourists.

It should not be forgotten that it is part of a Unesco World Heritage Site, widely regarded as one of the world’s most precious biodiverse, indigenous natural environments; but it will in future no longer offer low-cost garden entry to South African citizens through its long-established, Botanical Society (BotSoc) membership system.

The effect of a ruling by the South African National Botanical Institute (Sanbi) to eradicate this system has meant that instead of a member paying around R562 per year for unlimited entry to the garden, South African and SADC citizens will now pay R100 per adult and R40 per child under 18 per visit. A family of four who would have paid approximately R1,124 per year for unlimited free garden entry, will now pay around R280 per visit.

This is plainly unaffordable for most South Africans and, over the last 11 months the garden, a once popular and safe environment for South Africans, has visibly emptied out, and is now visited — as far as we have seen — mainly by overseas tourists (with the exception of Tuesdays, when South African pensioners have free access).

It seems that the objections from the Botanical Society and its members to this decision by Sanbi have fallen on deaf ears and, while the assertion has been made that the garden will remain economically viable, the financial effect of this loss of a highly lucrative income stream (over R6.1-million) is clearly visible in the consequent neglect of its upkeep and the recent call for “volunteer gardeners”.

A critical resource and safe space for all

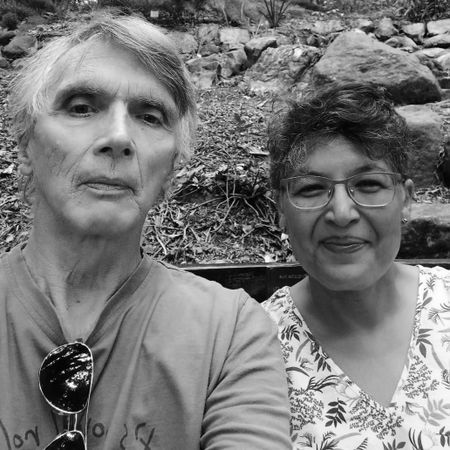

Rochelle was prompted to start writing this reflection while sitting high up on the slopes of Kirstenbosch. She was there alone, seeking solace in the soft, buttery light of the late afternoon as she awaited news about Kelwyn’s major surgery at a nearby hospital.

As she sat there, she reflected that, as an elderly woman, Kirstenbosch has been a place where she and many other women and children could feel safe — an unusual phenomenon in South Africa. This led her to contemplate the multiple roles that Kirstenbosch has played in her life and, in somewhat different ways, in both of our lives.

For Rochelle, who grew up on the Cape Flats during apartheid with restricted access to green spaces, it was a revelation to discover the extraordinarily diverse flora and fauna and the dramatic landscape of Kirstenbosch post-1990.

Kelwyn, previously accustomed to the grasslands and bushveld further north, found it a location where he could familiarise himself with the intricacies of the fast-disappearing Cape Floristic Region and its fynbos biome, threatened all around by urban development.

At the same time (given the span and variety of Kirstenbosch’s collection) it was a place of connection with plants and trees he recognised from other parts of South Africa.

Peace and environmental education

No matter where we have travelled, Kirstenbosch remains our special place. It’s the site at which we learned about indigenous plants and gardening and where we first became birders.

Together, we learnt the joy, deep peace and connectedness of being in nature and observing the sights, sounds and fragrances of the passing seasons, each of which brings its variety of birds, butterflies, insects and flowers: the pelargonium and buchu scents in their dizzying variations; the nesting spotted eagle owls, the stunningly pretty swee waxbills and other gleaning seedeaters; and – for us in particular – welcoming every spring the migrants as they arrive, including the unforgettable paradise flycatcher and darting black saw-wings.

We’ve seen the almost imperceptible changes in forests, streams and flowerbeds over the years, including the transfiguration of the aptly named Enchanted Forest from its early scrawny beginnings to its present abundant growth; and, as non-botanists, we have come over time to recognise many plants and trees by the appearance of their bark, flowers and leaves.

We are simply two of the many people for whom the garden is an ongoing learning experience.

It is also a place for the unexpected. For us, this would include the first time we came across the escapee flock of bronze mannikins that have settled in the garden; the unexpected flight of a honey buzzard over our startlement as we drank coffee; the boomslang which escaped our human inquisitiveness; the precious few minutes when we were abruptly face to face with a caracal kitten; and — alerted by the alarm calls of a flock of indignant white-eyes — the moment we were made aware of a wood owl hidden in thick foliage.

Of course, everyone who knows Kirstenbosch, or has spent any time at all there, will have their own reminiscences. Its beauty is that it has served many roles: as a place of peace and refuge; a play space for children, an outdoor teaching venue; a place for family outings and celebrations; a location for unexpected meetings with friends; a rendezvous supplying both conversations and the sharing of information; a base for hiking and photography; and so much more.

For all concerned, it is a place to test and hone one’s skills — whether these be botanical, photographic or birding — and to discover new natural wonders. We have seen this sense of surprise, and eagerness, on the faces of many people we pass by on our walks — especially children — expressed in differing ways through different languages.

Value of nature

For Rochelle’s activist parents, Kirstenbosch was an ambivalent space in which they experienced much joy in nature, but which also evoked painful, angry memories and stories of a past lived in Newlands and Claremont, the indignities of expropriation and forced removals under apartheid and the still ever-present weight of a vastly unequal society.

As a teacher in a working-class school, Rochelle’s mother and her colleagues deeply valued opportunities to introduce the children in the school environmental club to the joys of hiking up the mountain and observing nature.

When her speech and memory were erased by Alzheimer’s disease, she was no longer able to recover those memories and recount her stories, but she still seemed to appreciate Kirstenbosch anew each time. While she was usually anxious and restless in large crowds, on our weekend trips she gazed with obvious wonder at the sights and sounds of the garden and its restaurant, where the staff recognised her and made sure she had a welcoming cup of Rooibos tea almost as soon as we sat down.

We are aware that Kirstenbosch has had its financial problems, and that the dispensation that has now ended was a good deal. We see no problem with Sanbi adjusting Kirstenbosch’s membership fees from time to time by a reasonable and affordable percentage.

Read more in Daily Maverick: A closer look at the richness of South Africa’s biodiversity

But this decision which has now been made is — to put it mildly — extreme, and bears all the hallmarks of a bureaucratic edict out of touch with the social and, indeed, custodial objectives of the garden as these have evolved.

End of an era?

Movies and music concerts and fun runs may help redress some of the financial concerns, but it is our worry that, as the coffers seem to show no signs of swelling, the pressure to tweak Kirstenbosch into a theme park will increase.

It is more than likely that, in order to generate the necessary finances to maintain the site there will of necessity be a steady increase in loud, disruptive events. At worst, as financial constraints burgeon, we fear that branding and commodification may make this place we love unrecognisable.

There is a balance to be kept between preserving an environment, fulfilling a community role and remaining financially sound. Yet it should not be forgotten that Kirstenbosch is a World Heritage Site, and SANBI has an obligation to hold this precious garden in care for the people of this planet.

More than this: to share it. At the end of apartheid, Sanbi acknowledged that in the past they had served exclusively white interests, and made a commitment to serve all South Africans.

This latest U-turn seems likely to revert the garden to a place reserved for the wealthy and landscaped for transient tourists. While the entrance fee now inhibits locals using the garden on any regular basis, the higher fee for international tourists is still cheap for most of them, given the exchange rates (a friend from the Netherlands recently likened it to the price of two cups of coffee!).

At the same time, as the numbers of local visitors dwindle, we can only share the sentiment of that staff member who wondered to her friend within earshot: “What will become of us when there are no people to serve?”

Clearly, the garden needs viable income, but Sanbi needs to find solutions that go beyond superficial and stop-gap imperatives. It is a resource which belongs to all South Africans.

The need should be to focus on preserving its unique and rich biodiversity while adopting policies and pricing which will enable the majority of South Africans to appreciate and enjoy its beauty and be inspired to feel ownership and inclusion in the project of conservation. DM