As December 2025 draws to a close, South Africa’s macroeconomic scoreboard shows a string of technical victories. After years of energy-induced paralysis, power generation has stabilised, investor confidence has firmed under the Government of National Unity (GNU), and the country has exited the Financial Action Task Force’s grey list. On paper, the economy has finally begun to move again.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), South Africa’s real GDP growth – the economy’s output adjusted for inflation – was 1.1% in 2025, up from 0.7% in 2023. Nominal GDP, the unadjusted value of the economy, reached roughly $426.38-billion. Yet for millions navigating supermarket aisles, job queues and rising household costs, these numbers feel abstract rather than lived.

To understand why “good numbers” haven’t translated into relief, we need to look at how macroeconomic growth interacts with population, jobs, wages and household balance sheets.

The per-capita trap: Growth that doesn’t reach the person

Aggregate GDP growth only tells part of the story. When the economy grows, but the population grows too, the GDP per capita—the average “slice of the pie” for each person—may barely improve.

IMF data places South Africa’s GDP per capita in 2025 at $6,667. This represents a 4.7% nominal increase from 2024, but much of that reflects currency and price changes rather than broad-based improvements in living standards. The OECD’s 2025 Economic Survey notes that South Africa has seen subdued growth for more than a decade, meaning households are starting from a low per-capita base. Until GDP growth accelerates toward the 1.8%-2% medium-term target, many families will continue to feel as though the economy is standing still, even as national output ticks upward.

The employment lag: A recovery without jobs

For GDP growth to matter in everyday life, it must translate into jobs. Here, 2025 has offered only a weak transmission.

Reuters reported that the official unemployment rate rose to 32.9% in Q1 2025. The expanded unemployment rate, which includes discouraged work-seekers, reached 43.1%. The South African Reserve Bank’s (Sarb’s) December 2025 Quarterly Bulletin later recorded a decline in the official rate to 31.9% by Q3 but noted year-on-year growth in employment slowed to just 0.6%.

This shows the economy expanding without meaningfully absorbing labour. Persistently high youth unemployment means many young South Africans remain structurally excluded from the benefits of growth. GDP growth, in this context, is something observed on charts rather than felt in pay packets.

Real wages versus cost of essentials

Even those with steady employment faced modest gains. Headline consumer inflation rose only gradually to 3.6% by October, but the composition of that inflation eroded purchasing power.

The Sarb notes nominal remuneration per worker rose 5.1% in Q2, yet private-sector wage growth slowed. Real wages – income adjusted for inflation – grew just 3.1%, often offset by rising non-discretionary costs. For instance, meat prices jumped 11.4% in October due to supply constraints. When essentials rise faster than inflation, macro-level improvements fail to reach the household level, leaving families no better off in practice.

Macro stability versus household balance sheets

National balance sheets improved in 2025, but gains were unevenly distributed. Sarb data shows household net worth rose in Q3, largely due to higher asset valuations as the FTSE/JSE All Share Index hit record levels.

Yet most households contend with debt, not stocks. The ratio of household debt to disposable income edged down to 61.6%, but servicing that debt still consumes 8.5% of income. The OECD warns that meaningful improvements in living standards require structural reforms – better public transport links, easier access to jobs, and a less burdensome regulatory environment for small businesses – which have yet to fully filter through the economy.

Read more: The quiet January shock — why household budgets tighten before salaries do

Looking past the scoreboard

As 2025 closes, South Africa’s macroeconomic situation is healthier than two years ago. Improved electricity supply and prudent monetary policy have stabilised inflation and removed key growth constraints.

Still, 1.1% GDP growth is stabilisation, not cure. For headlines to feel like relief in 2026, growth must be faster, labour-intensive and inclusive. Until structural reforms bridge the gap between aggregate output and household experience, many South Africans will live in an economy that looks stronger on paper than it does in daily life. DM

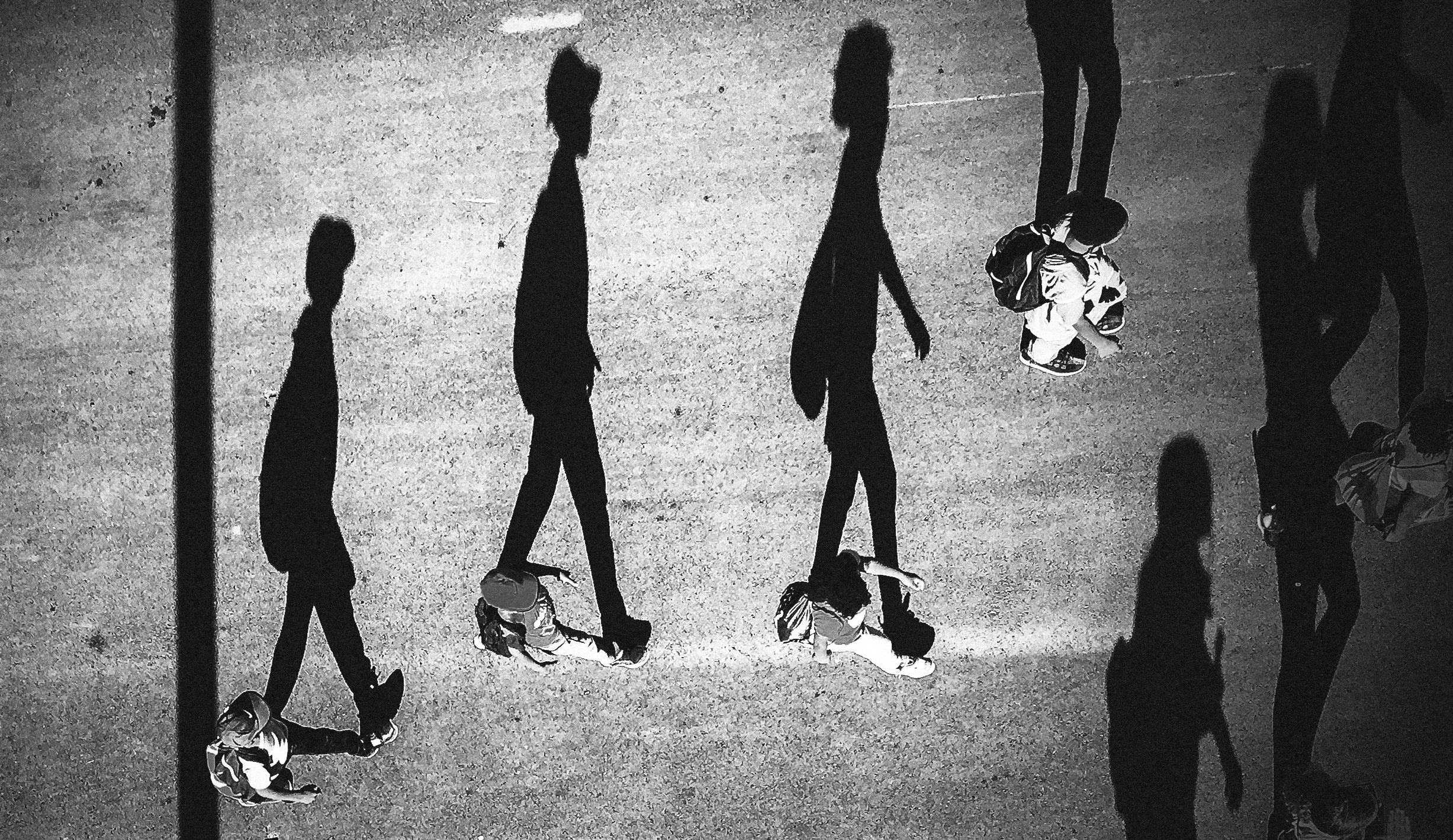

To understand why ‘good numbers’ haven’t translated into economic relief, we need to look at how macroeconomic growth interacts with population, jobs, wages and household balance sheets. (Photo: Tom Barrett / Unsplash)

To understand why ‘good numbers’ haven’t translated into economic relief, we need to look at how macroeconomic growth interacts with population, jobs, wages and household balance sheets. (Photo: Tom Barrett / Unsplash)