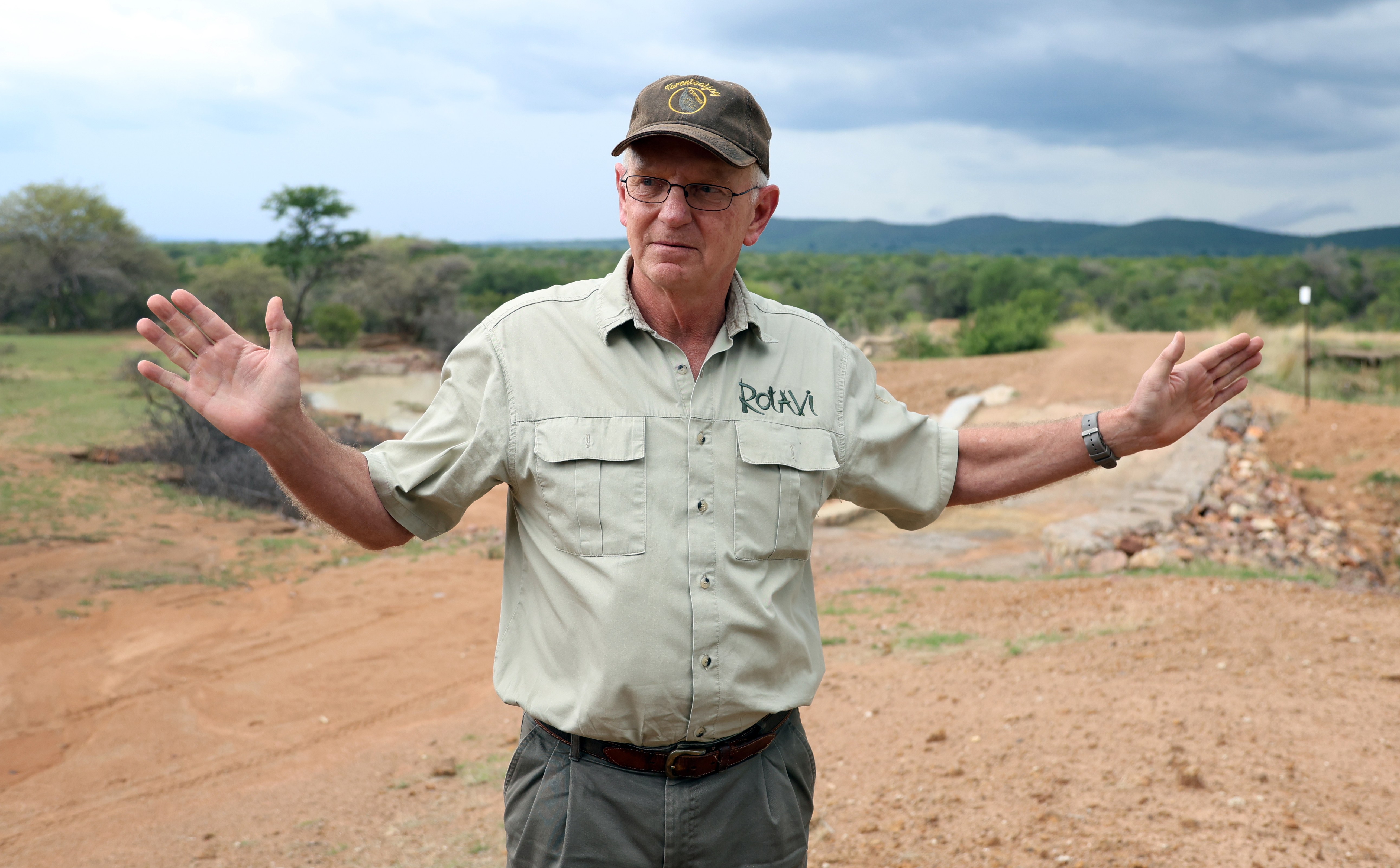

Standing in the damp Limpopo veld, Chris Ransome points to the green hills of Marakele National Park looming north in the distance.

“That is where the corridor will be,” he says.

Ransome, an affable accountant, has a vision: the dropping of fences and the establishment of corridors to link wildlife properties and farms in the southern Waterberg into a conservation haven for African wildlife known as the RoiSan Reserve.

The initial 12,000-hectare phase of this project was undertaken in January this year when the common boundary fence between Ransome’s Rotavi Private Game Reserve and the neighbouring Elandsberg Nature Reserve was removed.

The current goal is to drop the fences with other private game reserves that Rotavi shares long boundaries with to create a 40,000-hectare biosphere. Discussions are ongoing to reach this goal.

The long-term plan envisions links via corridors with other reserves including Marakele to create a wildlife sanctuary of more than 200,000ha.

A few of the neighbouring reserves have small elephant herds, and Ransome and his partners want to bring in more elephants – a move as rare as hen’s teeth these days.

“We plan to bring in 15 elephants from another Limpopo Reserve, otherwise they will be culled,” Ransome said.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/6I1A2724.jpg)

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/6I1A2668.jpg)

Asked about the costs, he said: “They are free and the current owner will dart and transport the elephants at his own cost.”

In short, the elephants are being given away at cost to the donor. It’s a buyer’s market right now for the pachyderms in South Africa.

The problem is that while there are willing, even desperate, sellers, there are virtually no willing buyers – even when the animals are free.

The RoiSan Reserve initiative is the exception, and is a telling example on a range of fronts which throw the vexed issues of elephant management into sharp and revealing relief.

Of fences and fragments

It all begins with a sturdy, electrified fence.

In South Africa, four of the Big Five that adorn our currency notes are all contained in fenced reserves. The leopard is the outlier because a fence is no barrier to this big cat.

This speaks to the fact that South Africa is the only industrialised economy in the world that is also home to the Big Five. It’s how an advanced economy, with a middle class and a commercial farming sector, responds to the presence of large, potentially dangerous animals.

That this apartheid-era measure has never been removed in the era of ANC rule and democracy speaks to another point: it’s the most effective way to prevent human-wildlife conflict, and its human victims are generally the poorest of the rural poor.

Fencing also has ecological consequences, and scientists and conservationists are still grappling with this issue.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/6I1A2646.jpg)

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/6I1A2625.jpg)

Across southern Africa, elephant populations are booming and there is no silver bullet for what many – though far from all – conservationists regard as problematic, as my colleague Tony Carnie has eloquently detailed in this publication.

Read more: No silver bullet to manage booming elephant problem in southern Africa

But certainly among South African game ranchers and private reserves that own elephants, the consensus is that the pachyderms in confined fragments of space eventually become an ecological and economic liability rather than an asset.

Many of the private reserves in South Africa that now have elephants were initially seeded by excess animals from large parks such as Kruger.

There is much debate about concepts such as “carrying capacity” and whether Kruger now has too many elephants – its population has soared in the past three decades to 30,000 from about 7,000.

But the associated ecological problems such as tree destruction rise at an accelerating pace as a reserve gets smaller.

The bottom line now is that most private reserves in South Africa with elephants cannot find new homes for the animals that they no longer want. It’s not like a dog that someone can adopt at the local SPCA.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/6I1A2600.jpg)

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/6I1A2588.jpg)

“Almost all, if not all, private reserves (and state reserves) that have elephants are overstocked in southern Africa. We cannot even give them away. We have all tried in many different ways with no success,” Malcolm Thomson, the general manager of the Pongola Game Reserve in KwaZulu-Natal and True Green Alliance director, told Daily Maverick.

“In most cases elephants no longer have value and are rather a net cost to the landowner, which negates any incentive to maintain them on their properties.”

Werner Schulz, who owns part of the 23,500ha Atherstone Nature Reserve co-managed with the Limpopo government, says the conservancy has a mammoth pachyderm problem.

“We have over 160 elephants and want to give away at least 120. And we need to reduce them immediately or else we will have to cull them. We have no option, they are causing ecological damage,” he told Daily Maverick.

But in the past three years they have found only one landowner who says he can take just five.

Culling is a last resort, and private owners must go through a long list of alternatives before provincial authorities provide the green light for the wrenching decision to pull the trigger.

These include contraception – in use in 47 parks in southern Africa – which limits growth but does not immediately reduce the population, range expansion if you can buy a neighbouring property, or selling or donating the animals if there are any willing buyers or donees.

Meanwhile, the perception among many private elephant owners is that the wider ecology suffers.

“We have lost 90% of our vulture nests because the elephants killed the trees. So now the vultures are nesting on properties outside the reserve where they become targets for muti or are shot by uneducated farmers,” Schulz said.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/6I1A2583.jpg)

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/6I1A2572.jpg)

Such views were echoed by other private elephant owners – who are on the frontlines of this issue – whom Daily Maverick approached for comment.

Elephants are “charismatic species” in the eyes of many humans, and because of their size, intelligence and elaborate social structures their welfare is often placed above that of other species – some animals are more equal than others.

But the problem in South Africa is ultimately the fence, which creates fragments of habitat like islands separated by the sea.

When Daily Maverick recently visited his reserve, Rasnome arranged table mats to explain his vision, placing them side by side on the table to represent his property and those adjoining it.

Another way to view this is to place a barrier between the mats, making them fragments. Like an island, there is eventually no more room on the mat for elephants – unless they are connected by removing the barrier or erecting a corridor to connect them.

Why elephants are needed

And there is another prism through which to regard this contested terrain.

Elephants in confined areas may inflict ecological damage that harms overall biodiversity. But removing the species entirely has other consequences.

The former has been the focus of intense debate, while the latter scenario is often overlooked. As a result, we don’t often see the forest for the trees.

“We have bush encroachment and this negatively impacts biodiversity. So we need elephants,” said RoiSan co-founder Rudolf Pretorius, whose reserve adjoins Ransome’s, as he drove his Land Cruiser along the dirt roads that snake through his property.

Standing in a veld surrounded by lush foliage, Pretorius said that 15 years ago there were 900 trees 2m or taller per hectare. That number now stands at 1,500.

Too many trees is as unnatural as too few, crowding out other plant species and encroaching on the grasslands needed for grazers as well as many bird and insect species.

This patch of the Waterberg bush had elephants more than a century ago, and they now haunt the landscape with their absence.

Elephants are what biologists term a “keystone species” – like the keystone of an arch, things fall apart when they are removed. Also known as physical habitat engineers, the species dramatically alters the environment through tree removal and the dispersal of vast amounts of dung and seeds.

And the ecological aftershocks of the removal of elephants has been witnessed on a global scale. The Pleistocene extinctions of mammoths, mastodons and other elephant species outside of Africa thousands of years ago – which the emerging scientific consensus holds was caused by “overkill” by Paleo hunters – triggered unnatural forest growth in regions such as Europe and the Americas.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/WFD_4780.jpg)

It’s a conundrum for elephant management in relatively small spaces where the animals must be fenced off to prevent human-wildlife conflict and to protect the species from ivory poaching.

On one hand, no elephants means an ecosystem devoid of a keystone architect. Alternatively, if there are too many, the animals may eat themselves out of house and home, with negative consequences for other species.

Taking the gamble

The people behind the RoiSan Reserve initiative are willing to take the gamble to rewild and restore the ecosystem’s integrity by bringing in more elephants in the hope that the issues that have risen elsewhere can be mitigated in the long run through the felling of fences and the carving of corridors.

The elephant density will also not be high – at least initially.

“The elephants will resolve some ecological problems for us and our plan is to expand,” said Pretorius.

Ransome’s property currently has white rhino – the numbers cannot be disclosed for security reasons, a common practice – and the animals are regularly dehorned as an anti-poaching measure. We saw a dehorned mother and calf sauntering through the bush as Pretorius was driving.

The reserve also has Cape buffalo which lack natural predators – a state of affairs that will dramatically change with a planned introduction of lions.

“We need to rewild this place. We are going flat-out for the ecosystem,” said Pretorius. “And the focus needs to be on game viewing and ecotourism. That has more economic value than hunting or game breeding.”

Not all conservationists and wildlife economists would agree with that sentiment, but “non-consumptive” ecotourism can certainly work here. Located not far from Bela Bela, the reserve is barely a two-hour drive from Johannesburg and has infrastructure such as the roads required for game drives and accommodation for guests.

The places in Africa where hunting – or “consumptive” ecotourism – is generally regarded as the more viable commercial option tend to be remote and lacking in amenities.

There are also wider economic spin-offs for the landowners involved in the project and the local communities.

Ransome pointed to how property prices soared when private reserve owners on Kruger’s western border removed their boundary fences with the park.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/6I1A2534.jpg)

“The value proposition is that once you join up the value of the land goes up because land prices here have been stagnant for 20 years. Beyond the ecological benefits there are economic benefits for the landowners,” Ransome said.

For the local communities, the initiative is seen creating badly needed jobs and opportunities for skills acquisition and small businesses.

The project also provides a fresh perspective on the often polarising issues around elephant conservation.

The image of elephants as agents of ecological damage is largely a product of the fences that confine the animals to limited ranges. And both are human creations.

Restoring the species to habitat it once roamed – and engineered – and expanding the range through corridors is surely an experiment worth trying. If nothing else, it inspires a sense of hope amid debates that have become as sterile as a landscape without wildlife. DM

Chris Ransome explains the dropping of the fences to allow elephants to roam between farms creating a safe haven for wildlife. (Photo: Felix Dlangamandla)

Chris Ransome explains the dropping of the fences to allow elephants to roam between farms creating a safe haven for wildlife. (Photo: Felix Dlangamandla)