Truth, lies and doughnuts

FORENSICS. I’d always associated that word with TV crime shows. I pictured the weather-beaten detective, tie askew, paper cup of steaming coffee in hand, looking on as the surgically gloved expert gathered and sealed the scraps of evidence in the blue glow of a taped-off scene. A snapped twig, a stray thread, a flake of paint: even the tiniest clues can help track down a suspect and solve a crime.

But as I discovered in the aftermath of HSBC Africa’s attempted hostile takeover of Education Africa, there is another branch of forensic science that is equally painstaking in its pursuit of the truth. Here, the experts glean their intelligence from spreadsheet cells, email threads, minutes of meetings, telephone conversations and interviews, and trace elements of digital data that testify to fraud, corruption, misconduct and other forms of economic wrongdoing. Rarely is this line of forensic work – slow, bloodless, mostly desk-bound – portrayed in heroic fashion on TV. Yet it turns just as much on the battle against the darker instincts and actions of human behaviour.

In an office park east of Pretoria, where rows of saplings grace a fortress of glass and stone, there’s a company called Phandahanu Forensics. ‘Our clients understand that this is war,’ proclaims the firm’s brochure. ‘We win the war.’ In 2011, after the retreat of the HSBC Africa occupiers from our office, Phandahanu went to war on our behalf. I saw it as a chance to clear our names, once and for all.

Phandahanu had initially been subcontracted and briefed by Edward Nathan Sonnenbergs (ENS), a large legal firm with a forensics division, but they subsequently took their brief fromWerksmans Attorneys. This convoluted legal arrangement was a result of HSBC having put a stop to ENS’s investigation, citing a conflict of interest.

Following the resignation of the trustees, an outside party once again occupied our office. This time, we welcomed them in. We had nothing to hide. The forensic investigators set up base in the boardroom, with coffee on tap. We let them get down to business.

Linda Gould and I, ‘collectively the directors of Education Africa’, as the report put it, were fully aware of the risks of subjecting ourselves to an independent forensic audit. But after a year of unrelenting intimidation, seven weeks of suspension and a flawed disciplinary inquiry that collapsed after a few days of hearings, we were prepared to do anything that might help to restore trust and rebuild our shattered organisation. We hoped HSBC Africa and the former trustees, who had been so determined to oust Linda and me as directors, would be just as open to putting their allegations and charges to the test.

As it turned out, they declined the opportunity to clarify and defend what they had helpfully put on the record.

There’s a famous principle of communication associated with Eliot Spitzer, former attorney general and governor of New York. He was known as ‘the sheriff of Wall Street’, until his extramarital indiscretions landed him in trouble with the law. ‘Never write when you can talk,’ advised Spitzer. ‘Never talk when you can nod. And never put anything in an email.’ Had Krishna Patel obeyed this principle, I would never have been privy to what he really thought about me, although, based on our occasional interactions, I did have my suspicions.

/file/attachments/2985/Daily-Maverick-high-res-Final-31102502_879595_5cba123ea0e46b102a77c3ad9129ff71.png)

In an email to his fellow Education Africa trustees on 26 February 2011, Patel wrote, ‘I have never in my long business career ever come across anyone who is as manipulative, disingenuous, cunning and morally bankrupt as James. EA doesn’t need James!’ He gave no clue as to what I had done or not done to make him blow his top.

As much as it can be a jolt to see ourselves as others see us, I wasn’t overly troubled by this glimpse into the behind-the-scenes correspondence that flitted from inbox to inbox just days after our suspension. I could shrug it off as a hiss of steam escaping from a pressure cooker. Far more hurtful was the allegation, unattributed but presented as plain fact, that I had mistreated schoolchildren on a week-long marimba band tour to Vienna in January 2011.

My memories of the tour – joyous performances in public spaces, bringing a lilt of South African rhythm to the city of Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms and the Strausses – were clouded by the attempt to portray me and my fellow organisers as callous, uncaring, penny-pinching thieves. Allegedly, in the freezing cold of an Austrian winter, we had fed the children on doughnuts and pocketed their tips for ourselves. This was the ‘height of cruelty’, wrote Angie Makwetla (who in my absence had taken on the role of interim CEO of Education Africa) in an email to her fellow trustees.

Indeed, it would have been, and on a Dickensian scale, with sugary pastry in place of gruel, had there been any truth to the allegation. Picture the public scandal if just one parent of just one child had made such a claim against a charity devoted to bettering the lives of the poorest of the poor! Instead, the scandal was that the claim – ‘clearly defamatory’, according to a high-level synopsis of the forensic report – had been made at all.

A quick caveat before we proceed. While the term ‘forensic’ comes from the Latin forensis, meaning ‘in open court’, a forensic investigation does not have the legal authority to compel people to testify or provide evidence. Hence, Angie Makwetla wasn’t required to reveal the source of the allegations she’d broadcast in her group email.

Getting to the truth of the matter was the equivalent of searching for a doughnut and finding only the hole. The forensic investigators had to look further afield to fill in the gaps. Dr Stefan Pistauer, Austrian trade commissioner at the time, who helped smooth the way for the tour, was outraged by the allegations. The children were never ill-treated, he said. They ate the same food as the adults did at the venues where they performed.

The investigators also interviewed Irene Gröpel, a coordinator and fundraiser for Friends of Education Africa in Vienna. Yes, she confirmed, it does get ‘very very extreme cold’ in Austria in winter. Regarding the children on the tour, she wrote, ‘One day I came to the accommodation to pick them up and they showed me that they had built a snowman. They were even playing football on the court. I asked them if it is not too cold for doing that – because I feel the cold very easily – but they said no, it’s fun.’

Irene had accompanied our group to events and outings, where part of her duty was to tally the marimba band’s earnings from tips and the sale of CDs. This she’d done with great care, detailing the earnings in a spreadsheet that showed a grand total of €4 597.19 for the week. All this, she banked on behalf of Education Africa.

And what of the doughnuts? I’ll admit, I have an extremely sweet tooth. Oh, how I long for the days before I was confined to a gluten- and lactose-free diet, a side-effect of the extreme stress brought on by the HSBC saga. But yes, as I recall from the tour, there were, occasionally, doughnuts – just not to the exclusion, as Angie Makwetla’s email had suggested, of all other forms of sustenance.

Tshifhiwa Tshililo, a music teacher at Masibambane College, was also with us on the tour. He told the forensic investigators he was unaware of any complaints from the children. Their three daily meals included such childhood favourites as pizzas, chips and chicken. And while it had been cold on the tour, he noted that the children had enjoyed their indoor and outdoor performances and excursions. DM

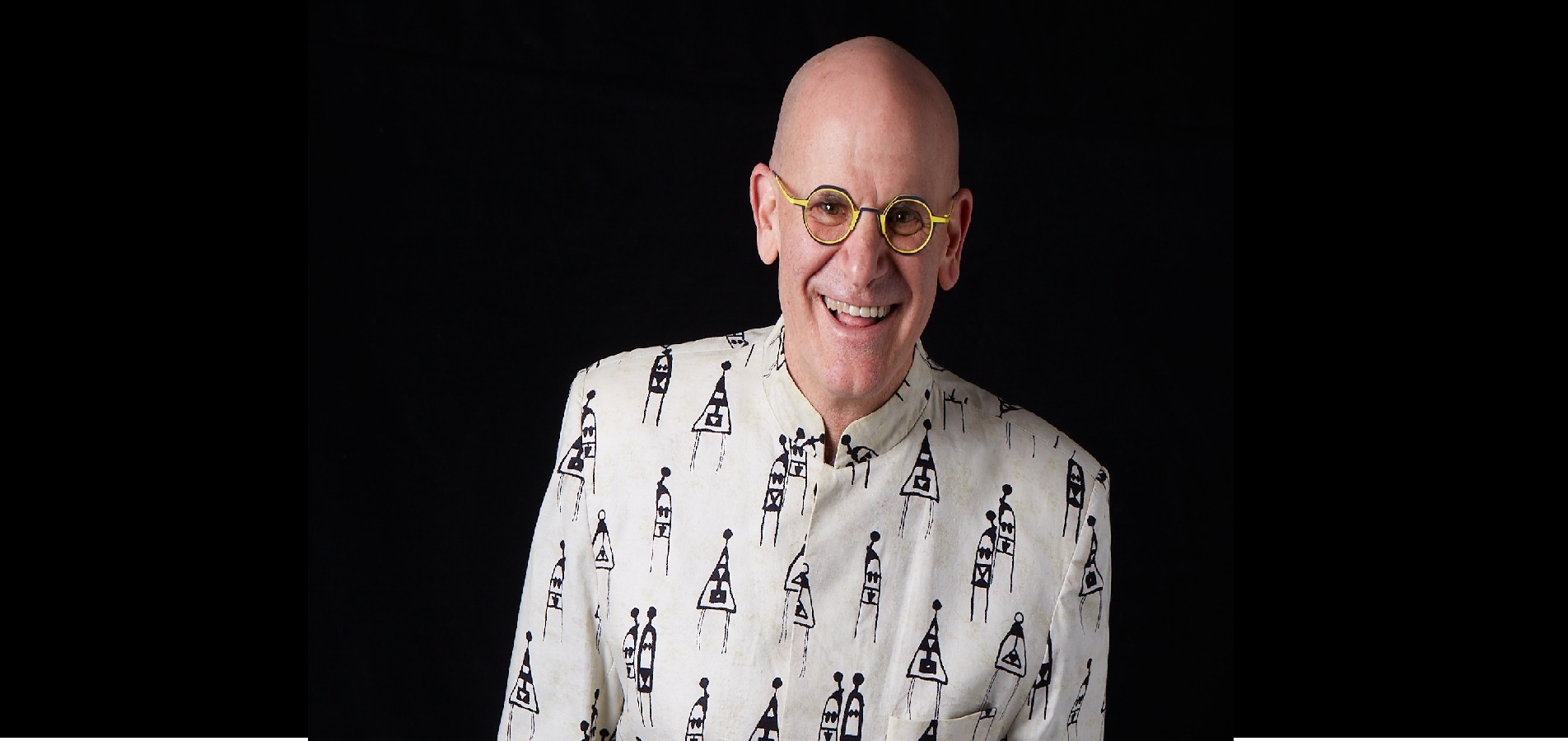

Author: James Urdang, Founder & CEO of Education Africa; humanitarian, social entrepreneur and motivational speaker

James Urdang, author of It Always Seems Impossible.

James Urdang, author of It Always Seems Impossible.