It’s a meditation on the beauty, fragility and mystery of the marine world, written and photographed with the clear conviction of two people who have devoted their lives to bearing witness to wildness before it disappears.

The Pickfords are veteran South African wildlife photographers and this book distills four years of global fieldwork across the five great oceans – from the Transkei’s surf-pounded cliffs to the atolls of the Seychelles, from the coral gardens of Ningaloo in Western Australia to Cuba’s pristine Jardines de la Reina. Their project is monumental in scope but deeply human in tone: it’s a travelogue of awe, anger and moral reckoning.

At 35cm high it’s a really big book, but that gives generous space to display the photographs. There are also no page numbers so you get uncluttered spreads of nearly half a metre wide. The type is in separate sections, though the type size could be bigger for an easier read.

/file/attachments/2984/Elephant-seal-pup-South-Georgia-off-Antarctica_1_298389.jpg)

/file/attachments/2984/Walrus-Svalbard-Norway_1_355373.jpg)

The book opens with an intimate childhood memory: Peter learning to swim in the cold seaside pool of his South African hometown, coached by a man who encouraged rather than scolded. From this scene – vividly recalled – the narrative expands to planetary scale. “Through him,” Peter writes, “I became fluid in the sea and it opened my life to two parallel universes: land and water.” This sentence encapsulates the book’s philosophy: that humanity lives in two overlapping worlds and must learn again to move with grace between them.

The ocean is presented not as a backdrop to human life but as its original and sustaining source – “the largest universe existing on our planet.” Yet, as the authors argue, most of us stand at its edge and see only the surface.

They are unsparing about the consequences of this blindness: factory ships scraping krill from Antarctic waters, seabirds starving as industrial fisheries drain their food supply and governments using sanitised terms like “sustainable use” to disguise exploitation.

What rescues the book from despair is its conviction that wonder itself can be a form of resistance. “It is not legislation, law, or policing that truly protects wilderness,” they write, “but reverence.” The aim of Wild Ocean is to rekindle that reverence.

/file/attachments/2984/Plolar-bear-in-Svalbard-Norway_1_152058.jpg)

/file/attachments/2984/Bottlebose-dolphins-Wild-Coast-South-Africa_1_555973.jpg)

The Wild Coast

The first journey takes the reader to the Transkei Wild Coast of South Africa, a landscape of cliffs and estuaries “like a gigantic ribcage against the sea”. The writing here is of remembered belonging. Peter evokes dawn mist coiling through gorges, hilltop rondavels in faded turquoise and pink and fishermen trudging barefoot with surf rods and woven bags.

These passages, though attached to specific photographs, read like prose poems – immersive and attentive to small gestures. A young girl in a burgundy dress curtsies shyly as she accepts a fish carcass; her presence becomes a moral axis for the chapter.

/file/attachments/2984/Breaching-humpback-on-the-Transkei-coast_1_961907.jpg)

/file/attachments/2984/Common-dolphins-Wild-Coast-South-Africa_1_798229.jpg)

One of the book’s threads is the idea of “ocean warriors”. The authors draw a line between the Wild Coast’s environmental defenders – figures like Sinegugu Zukulu and Nonhle Mbuthuma, who halted offshore oil exploration – and the quiet courage of the local people who live “off the land, not on it”.

In a moment of quiet revelation, Pickford recognises the thin, barefoot girl from the beach as a warrior too: someone whose intimacy with place is its own form of resistance. It’s a powerful argument for rootedness and humility as conservation ethics.

/file/attachments/2984/Galapagos-penguin-Isabela-Island-Galapagos-islands_1_805499.jpg)

/file/attachments/2984/Manta-ray-St-Francis-Atoll-Seychelles_1_143940.jpg)

The Seychelles

From South Africa the narrative flows north and east to the Indian Ocean’s atolls. On Astove and Cosmoledo the tone shifts from grounded realism to lyricism. The Pickfords’ description of green turtles nesting under starlight is both forensic and reverent – “the eggs come in a rush, ten, plop, plop, plop… pause”. They juxtapose this abundance with the long history of human plunder: hawksbill turtles slaughtered for jewellery, seabird eggs harvested by the million. Yet they also celebrate the resilience of the natural world when left alone.

On Cosmoledo, flocks of sooty terns fill the sky “like a blurred confetti of wings”, a scene so excessive in vitality that it leaves the authors “giddy with joy and pierced with sadness for all we have lost”.

The moral question that arises – “why would anyone want to spoil that?” – lingers over the pages. The authors’ answer is stark: some take profit from nature’s generosity, others take joy. Between these two human impulses, the fate of the ocean will be decided.

/file/attachments/2984/Whale-shark-over-Ningaloo-Reef-Western-Australia_1_417370.jpg)

/file/attachments/2984/Goliath-grouper-Exmouth-Gulf-Western-Australia_1_761142.jpg)

/file/attachments/2984/Whale-shark_1_701094.jpg)

/file/attachments/2984/Blacktip-reef-sharks-Palau-Micronesia_1_925502.jpg)

Ningaloo

In the chapters on Australia’s Ningaloo Reef and Exmouth Gulf, the narrative merges natural history with personal adventure. The Pickfords trace the reef’s geological evolution back 250 million years, and plunge into its present-day vibrancy: octopuses courting among corals, whale sharks gliding past, manta rays rolling through clouds of plankton “like giant black-and-white sails lifting in a calm breeze”. Their prose matches the rhythm of the sea itself – alternately still, tumbling and rapturous.

Yet even here, under the banner of Unesco protection, menace creeps in from the horizon. The Exmouth Gulf, they note, remains outside the heritage zone and is targeted for industrial exploitation. The contrast between the song of whales beneath the water and the “aura-like glow of industry” beyond the reef captures the tension at the heart of Wild Ocean: beauty and threat coexisting in the same frame.

/file/attachments/2984/Caribbean-reef-sharks-Cuba_1_159975.jpg)

/file/attachments/2984/Pink-anemonaefish-Palau-Micronesia_1_427060.jpg)

/file/attachments/2984/Shoal-of-Boga-Jardines-de-la-Reina-Cuba_1_525830.jpg)

Jardines de la Reina

Later chapters take readers to Cuba’s Jardines de la Reina, where coral gardens flourish under strict protection. The Pickfords recount the legend of Jacques Cousteau persuading Fidel Castro to preserve the archipelago – perhaps apocryphal, but symbolically true. Diving there, they find reefs unchoked by pollution, giant barrel sponges older than empires and an abundance of sharks that testifies to the ecosystem’s intactness. It’s an image of what the oceans once were and might again become if given sanctuary.

/file/attachments/2984/Marine-iguana-Santa-Cruz-Island-Galapagos_1_924363.jpg)

/file/attachments/2984/Galapagos-seals-Galapagos-Islands_1_116990.jpg)

The success of Wild Ocean lies in its fusion of image and word. The palette of photographs is thrilling: whales breaching against storm surf, turtles haloed in turquoise light, aerials of coasts that seem both ancient and untouched.

At times the moral urgency verges on sermon, but it never collapses into despair. The Pickfords’ tone is one of invitation rather than accusation. “Just put on a mask and lower your face into the water,” they urge. “It will write on the pages of your life stories you will want to retell.” Their faith is that intimacy breeds protection – that by knowing the sea, we will defend it. DM

The retail price is R1,100 (incl VAT) in most bookshops or online. It’s published in South Africa by Flyleaf publishing & Distribution. A new edition of their book Wild Land has also been released simultaneously and is available in a smaller edition at R850 retail.

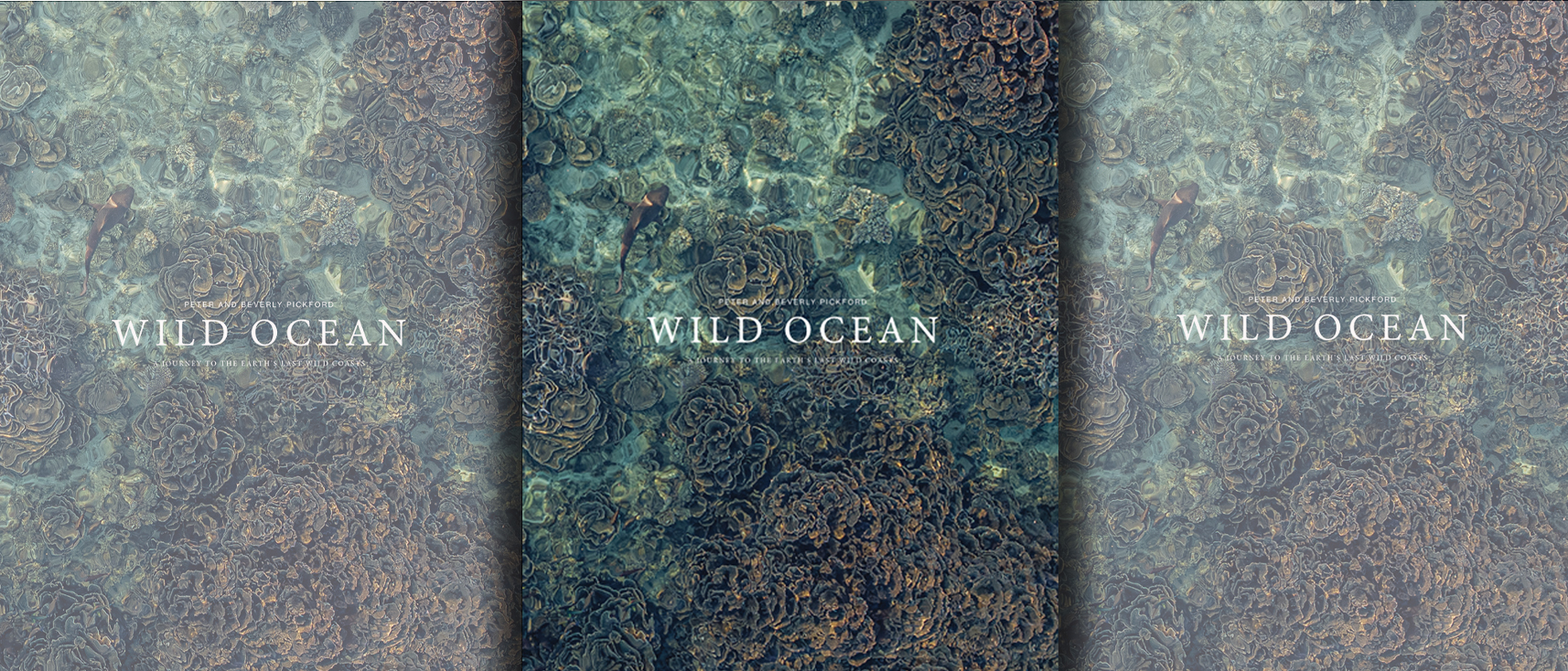

Wild Ocean Book Cover. (Cover: Peter and Beverly Pickford)

Wild Ocean Book Cover. (Cover: Peter and Beverly Pickford)