/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/label-Op-Ed.jpg)

Amid the concerning updates emerging from the COP30 processes in Belém, from missed emissions targets to wavering commitments from wealthy nations, one surprisingly empowering truth has come into sharp focus: the most important solutions for South Africa’s climate future lie within our own control.

We cannot dictate the pace at which industrialised nations cut carbon emissions. We cannot force donor countries to finally deliver the climate finance they promised. But we can decide how we prepare, how we adapt, and how we protect the development gains that matter to us.

/file/attachments/2984/ClimatecartoonforDMarticle_page-0001_194740_257ac7b92c23d14fefdb89c442365323.jpg)

This moment calls for strategic ownership. And within South Africa, one sector extremely well placed to take up that role is organised philanthropy, the constellation of private foundations, corporate social investors, family offices, community foundations and high-net-worth funders who already invest deeply in education, health, food security, early childhood development, youth livelihoods and community wellbeing.

From global disappointment to local leadership

The messages from Belém are sobering. The world is not on track to meet mitigation targets. Global North countries are backtracking on earlier commitments. And discussions on adaptation targets remain slow, complex and politically tense.

/file/attachments/2984/7_796640.jpg)

These facts require us to rethink many assumptions about development and social justice and to make ourselves more aware of the need to control our own destiny: countries in the Global South must seek to lead where the global system has faltered.

That leadership includes national governments, yes, but it also explicitly includes civil society, businesses and philanthropy. Recognising this, the COP30 presidency has called for NGOs, funders, community groups, researchers and local leaders to play a far greater role in advancing climate resilience.

They have termed this “mutirão” (collective effort), an opportunity to shape our own future.

Climate change is already reshaping every area philanthropy invests in

South Africa is already experiencing climate-driven disruptions.

Heatwaves are reducing teaching hours and damaging school infrastructure. Floods in the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal are destroying clinics, roads, community centres and homes. Water shortages are undermining livelihoods and food systems. New health risks are emerging, and vector-borne diseases are also shifting with the climate. Small businesses and informal workers are experiencing lost income and rising volatility.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/MC-KZN-Flood-Victim.jpg)

Climate change is the context shaping every development challenge and every philanthropic investment.

It is also a social justice and equality issue.

South Africa’s Constitution has social justice and human rights in the bedrock of its preamble; but reversals in rights to basic education, health and wellbeing as well as access to needs as fundamental as sufficient food and water are a threat to social justice, deepen inequality and accelerate social fragmentation.

Just as with Covid-19, global heating takes its toll on the most socially vulnerable in society, children, women and people with disabilities. As it exacts a price on communities, increasing pressure on resources, it will exacerbate ills like gender-based violence and mental illness. United Nations experts have also pointed out how it adds fuel to the rise of authoritarianism and narrowing democratic space.

This is why advancing equality and social justice is the best insulator against climate disaster: it is a prophylaxis that reduces vulnerability and increases capacity to find local solutions.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/MC-Climate-Fire_6.jpg)

Some civil society organisations, such as SECTION27, are already stepping up to the challenge of adaptation. Philanthropy can give a boost to this shift.

For these reasons, organised philanthropy must now see support for climate justice, adaptation and resilience as central to mission fulfilment. If foundations and high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) do not integrate climate into their giving, the programmes and sectors they care most about will become increasingly unsustainable.

Boards of foundations have a fiduciary and moral responsibility

Boards of philanthropic foundations hold both the governance responsibility and moral authority to ensure that their organisations remain relevant and impactful in a climate-charged world.

The questions boards should now ask themselves include: Are we ensuring that our strategy is climate-resilient? Do our grantees have the tools and resources to plan, understand the implications for their areas of work and adapt? Have we formally acknowledged climate risk in governance and grantmaking? Are we preparing our foundation for the realities of the next 10 to 20 years?

This is precisely why the South African Philanthropy Commitment on Climate Change, developed by the Independent Philanthropy Association of South Africa (Ipasa) as part of the global climate philanthropy movement, is so important. It provides a structured entry point for funders, from beginners to advanced actors, to assess their funding portfolios, build resilience and integrate climate considerations into their strategies.

For boards seeking clarity, alignment and a framework for action, the commitment is an essential tool. And if there was any doubt about the tangible difference funders can make when they commit their minds and resources to climate action, Ipasa’s newest climate change case studies offer powerful proof.

These case studies showcase South African funders who have integrated climate resilience into early childhood development work in KwaZulu-Natal, demonstrating how even modest funding can catalyse systemic change, strengthen community resilience and protect vulnerable children from climate impacts. From food gardens that serve as outdoor classrooms, to water-harvesting projects that ensure continuity of care during droughts, these stories reveal what becomes possible when philanthropy embraces climate as central to its mission.

Why HNWIs matter in this moment

High-net-worth individuals play a major role in South Africa’s social investment landscape. Their giving is typically personal, flexible, values-driven and deeply connected to family heritage or social commitments. Issues HNWIs care about are typically education, health, poverty, arts, gender, youth and food security.

A shift to integrating climate considerations into issues they care about is not visible currently, yet climate impacts threaten the sustainability of every area HNWIs invest in.

If philanthropists fund health but ignore climate, they will face rising climate-related disease burdens. If they fund basic education or early childhood development but ignore climate, schools will face closures and damage. If they support food systems without climate resilience, their impact will be short-lived. If they fund social justice without encompassing climate justice, inequality will deepen.

HNWIs simply need to ask: how does climate stress intersect with my giving? What can I do to strengthen the communities and issues I care about? And what can I learn from other funders who are already responding to climate change.

Many are already funding solutions that could be amplified through a climate lens, such as water security, youth entrepreneurship, early childhood development, community health workers, local food systems, skills training and informal settlement upgrading.

The opportunity is enormous.

Adaptation is where philanthropy and HNWIs can make the biggest difference

Mitigation, taking actions that reduce the drivers of climate change, remains essential globally. But for South Africa, adaptation, climate-proofing social systems and communities, is where the greatest developmental risks and opportunities lie. The work of Ipasa members, the Social Change Assistance Trust, the Hlanganisa Community Fund for Social and Gender Justice, and the Southern Africa Trust, who focus on community-based and community-led climate justice, exemplifies what is possible when funders team up with communities in the fight for climate resilience.

Adaptation is not about “surviving disaster”. It is about proactively strengthening local systems, protecting vulnerable communities, building resilience into development programmes and ensuring long-term sustainability.

Philanthropy is especially well positioned to fund adaptation because, through existing relationships and networks, it can support community-led innovation, fund experimental models, scale what works, build collaborative networks and take risks the government cannot.

Adaptation is also profoundly aligned with South Africa’s social justice tradition. It centres the communities most affected. It values indigenous knowledge. It strengthens collective resilience.

Organised philanthropy has a catalytic role to play

The role of philanthropy in climate adaptation is not symbolic, it is structural. It involves signing the South African Philanthropy Climate Change Commitment, integrating climate risk into due diligence and grantmaking and impact investing, supporting grantees to build climate resilience, pooling resources with other funders to scale solutions, prioritising locally led adaptation, and advocating for climate justice in national forums, such as the Presidential Climate Commission.

Ipasa also connects South African philanthropy to the global Philanthropy for Climate network through the climate pledge and by being the South African Climate Philanthropy Ambassador for the Worldwide Initiatives for Grantmaker Support (WINGS) – the only global network of philanthropy support and development organisations.

Importantly, this work complementary to, not duplicative of, government initiatives. South Africa’s Just Energy Transition represents a historic commitment to shifting away from coal while protecting workers and communities. But the government cannot do this alone. Philanthropy and HNWIs can fill critical gaps that large-scale policy initiatives often miss, supporting the community-level adaptation, skills development and social safety nets that make transitions just and equitable. Where the government focuses on infrastructure and industrial transformation, philanthropy can focus on people, ensuring that vulnerable communities are not left behind and that local resilience is built from the ground up.

This is also where philanthropy’s unique strengths truly shine. Philanthropy can seed new initiatives, test innovative approaches and get promising solutions ready for scaling and broader investment. It can take the kinds of calculated risks that the government and commercial sectors often cannot.

But this requires a shift in mindset.

Philanthropy must be proactive rather than reactive, must grab opportunities as they emerge, and must apply its collective intelligence to a fundamental question: how can we use the climate crisis as a catalyst for systemic change that creates a more just and equal society? In a country marked by profound inequality, climate action offers a rare chance to reimagine our social contract, to centre those most vulnerable and to build systems that work for everyone, not just the privileged few.

This is a way of ensuring the sustainability of philanthropic missions while strengthening the national climate response and at the same time entrenching a more socially just society.

A moment rich with agency

The messages from Belém reveal a sobering global truth: the world will not deliver the scale of climate action we hoped for.

But they also surface a hopeful South African truth, something we have realised at other moments of peril in the history of our country: we have the capacity, knowledge, networks and leadership to shape our own path forward.

Organised philanthropy can contribute meaningfully to that path.

If boards embrace climate risk, if philanthropists see the climate connections to their giving, and if funders collaborate rather than operate in silos, South Africa can build a future that is not only resilient, but more just and more equal than the present.

The future is not predetermined. It is shaped by the choices we make now.

Philanthropy has the tools. The country has the knowledge. Communities have the solutions. DM

Louise Driver is executive director of the Independent Philanthropy Association of South Africa, a membership-based philanthropy forum which promotes, advances and supports philanthropy in South Africa. Before joining Ipasa, Louise was CEO of the Children’s Hospital Trust at the Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital.

Dr Zuziwe Khuzwayo is the social justice project manager at Ipasa, where she coordinates a network of local and international donors who advocate for more social justice funding in South Africa. Previously, she worked at the Ford Foundation as a global programme associate, focusing on gender-based violence affecting women, girls, LGBTQI+ individuals, indigenous women and disabled women.

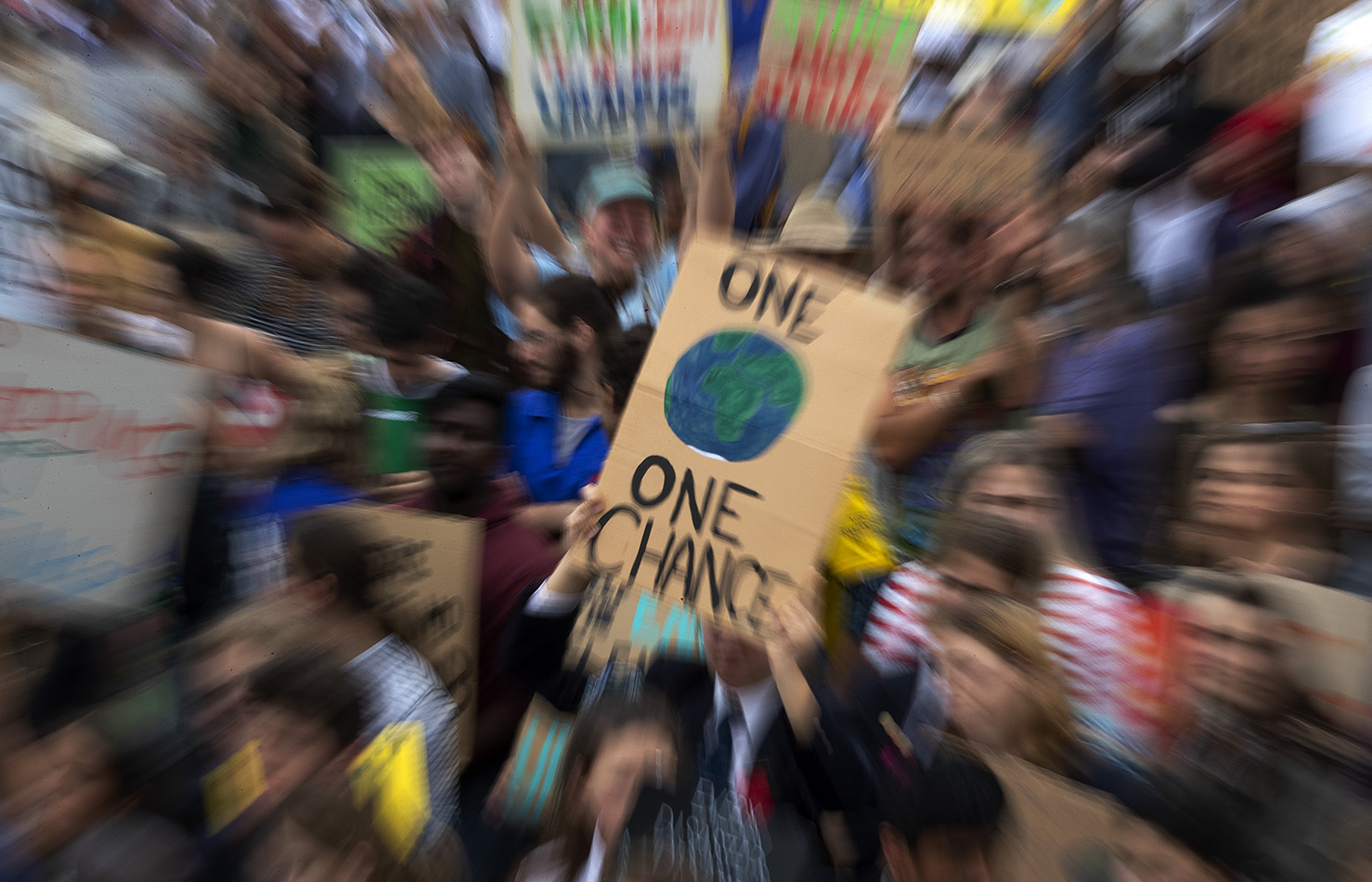

Protesters take part in the Global Climate Strike as they march to Parliament in Cape Town on 20 September 2019. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Nic Bothma)

Protesters take part in the Global Climate Strike as they march to Parliament in Cape Town on 20 September 2019. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Nic Bothma)