Through the lens of her father’s 40-year ministry at a Presbyterian church in Cape Town’s northern suburbs, Hannah Botsis explores faith, family and racial privilege with unflinching honesty in her memoir, A Clergyman’s Daughter. A meditation on grace and belonging, this story illuminates how communities navigate change while wrestling with their complicated histories. Here is an excerpt.

***

While the church stumbled along, learning how to care for its changing community, the city centre was rapidly transforming.

“Downtown Bellville was suddenly no longer nice and white, it was dubious, then it wasn’t white at all, and the nature of the businesses began to change, and began to change fast. Food began to change, clothing stores began to change, the Holiday Inn became nothing for a long time, then it became student accommodation, then it became a multiracial old-age home. These were big changes.”

In the course of a decade, the question of who and what Bellville Presbyterian Church (BPC) was and should be, and to whom, required an existential about-turn.

I guess it was also around this time, let’s call it the mid-nineties onwards, me cruising towards puberty, that I became more aware of race, or that I came to understand that people spoke in euphemisms about their fear and discomfort. And I knew that the target of this discomfort was The Other. Without contradiction, people in our congregation could speak of loving their neighbour, they could donate food, worship the Lord Jesus, and speak about “the Blacks” and “the Coloureds” as if they were a completely different category of being.

I recall what is probably a composite memory: a grandmother going to some Gogo-like hangout in a church hall for a charity knit-a-thon or similar, and reporting back to the congregation that she’d realised we’re all human and isn’t that nice and we all have grandkids and we’re not so different after all, praise the Lord.

Was that real? What was going on here? What was the role of faith in maintaining and/or overcoming those boundaries? And how successfully was that done, really? These were the same people that reacted with badly disguised anxiety when they learnt I would be going to the government high school closest to our home, which was by this time minority white and majority Coloured. How did the psychology of racism work? I was deeply puzzled by this. I didn’t have the tools to understand my social situation.

“I wrote my own private submission to the Truth and Reconciliation, that was something you could do then, confessing my failure,” my father told me. “How do you sound genuine when you say, I’m sorry, I could have done more? When you didn’t. How do you—” he breaks off. “What do you actually mean, you could have done more? When you look at the guys who did more: what did they actually do?”

I have deep empathy for this irresolvable internal contradiction. I think many white South Africans feel their lives were or are lived at an impasse. As a teenager and student, I longed for parents with a more radical history, a more progressive story; but now as an adult and parent, I see how easily the myopia of life sucks you in. Almost without realising it, the countless small decisions you make create a world which becomes your moral universe, and you wonder, how did that happen? Does this life I’m living reflect the values I supposedly hold dear? And how does Christianity fit into this? Do forgiveness and the unconditional love of Christ let me off the hook? Or should they pierce my heart and provoke action?

“I, I, I,” my father stammered, “I could have pushed Bellville much more, much harder, in getting rid of some of those racist attitudes. I could have preached more about them, I could have – we did have some meetings with people in the townships, and peace committees and whatever, going to have meals and then people coming to have meals with us – but there were very few participants. I think as a white Christian minister, I could have done a hell of a lot of more.

“When the riots blew up in ’86, you were two or three years old, our church in Nyanga was occupied by about six hundred people, and they were just desperate for all sorts of help. I put you in Fred Simons’ bakkie, loaded it up and off we went. Right to the heart of Nyanga.”

The Nyanga Presbyterian Church is located opposite the community centre (“where they had necklaced someone”), sandwiched between the bus and taxi rank.

“When I mentioned to some people that I’d taken you with me, they thought I was insane. But we would have been the safest people around.”

My father made a habit of reading the minutes of old session meetings. He found some from the 1950s, and came across an approach from a Coloured man who was being forcibly removed from his home in Bellville to Bellville South, the newly demarcated Coloured area. He was asking for help.

“The letter said I’m not a member of your congregation, but I am a Christian man, a member of a Coloured church, and we are being moved out and we are asking you for help. Essentially the request was: stand with us and oppose this.”

“One of the first maids Mom and I had used to live up in Oakdale [a poorer suburb of Bellville]. One afternoon I was driving her somewhere, and we passed through Oakdale and she said to me, ‘I used to live there.’

“‘Oh, really? What do you mean? You worked there?’,” I said, ignorant as anything and thinking she must be confused somehow.

“‘No,’ she said, quite clear, ‘I lived there’.

‘There was a pause, because I could not figure out what she meant, or how that was possible.

“‘It was my father’s house,’ she said, filling the silence.

“And I said, ‘When was it your father’s house?’

“‘We were moved out,’ she stated simply.

“Before then, I had had no idea that Bellville had been a mixed area.”

Unknown to many (whites, I should say), until at least the mid-1950s, most black Africans did not live in official apartheid “locations” such as Langa, but in privately owned and rented flats and houses throughout the Cape. This predates our living memory, but it shows up apartheid’s anachronisms. In the 1950s, however, Cape Town “became a test case for influx control and racial segregation”. “Government policy, implemented by local authorities, forcibly removed the African population to official ‘locations’ or endorsed them out of the area altogether.”

Between 1953 and 1958, the municipalities of Goodwood, Parow and Bellville and the Cape Divisional Council took the decision to forcibly remove all Africans living in shantytowns in the area to shacks in Nyanga. Those who refused to move were arrested and charged. Some 2,499 people were removed from Oakdale Estate in Bellville and from Goodwood in 1957. According to census figures, between 1951 and 1960 the number of Africans living in the Bellville area was reduced from 2,172 to 472.

So, here is my father reading in the minutes about the letter from a Coloured man asking for help.

“He is saying we have been happy living here and now we are going to be removed and our houses bulldozed. Please help us. There was a long discussion. And the minute read, ‘and the session resolved that they could do nothing’. And I don’t know, it broke me, Hannah, I read it and I started to cry. I just thought, how is it possible that a group of Christian men, twenty-seven of them, decided they could do nothing?”

All the information I could find about forced removals in Bellville pertains to Black Africans, not Coloured residential areas. But history speaks for itself. The present-day geography of Bellville and Bellville South, and who lives on which side of the railway tracks, is not hard to work out. I am not so much concerned with the factual accuracy of the letter in the minutes or archived policies on Group Areas, as I am in how the BPC session dealt with this request.

The mid-1990s were a time of deep reflection and reckoning for our nation, the horror of our history and present on full display at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. It was also a time of naïve hope. That perhaps here was a new beginning.

“So I decided to bring these old minutes to the session. I said I’ve been reading the minutes and came across this. I would like us to minute our repentance of that decision so many years ago. That we think about this tonight, and we say, that was a wrong decision, and we minute, we write down before Christ, that we repent that. Let us acknowledge that we corporately failed in our Christian duty.”

Only one other person voted for the proposed motion. There was no repentance. An elder and close friend of my father said to him, “You are asking them to do what they don’t understand.”

“What do you mean, ‘them’? You did nothing,” my father spat back.

‘“Well, I prefer to abstain from these political things.”

‘“That’s bullshit man, they did nothing, you did nothing, because you did not want to do anything.”

“You can’t repent for other people’s sins.”

“Yes, you can. Corporately, as a body, you can, and you should.”

“It was a lonely moment for me, Hannah. Where you think, what the hell have they learnt? What have I taught? That they can’t understand. You are the same body in Christ. You are the elders of the church. It is your history. The continued racism in the country, the blame for it, must lie at our feet.’ DM

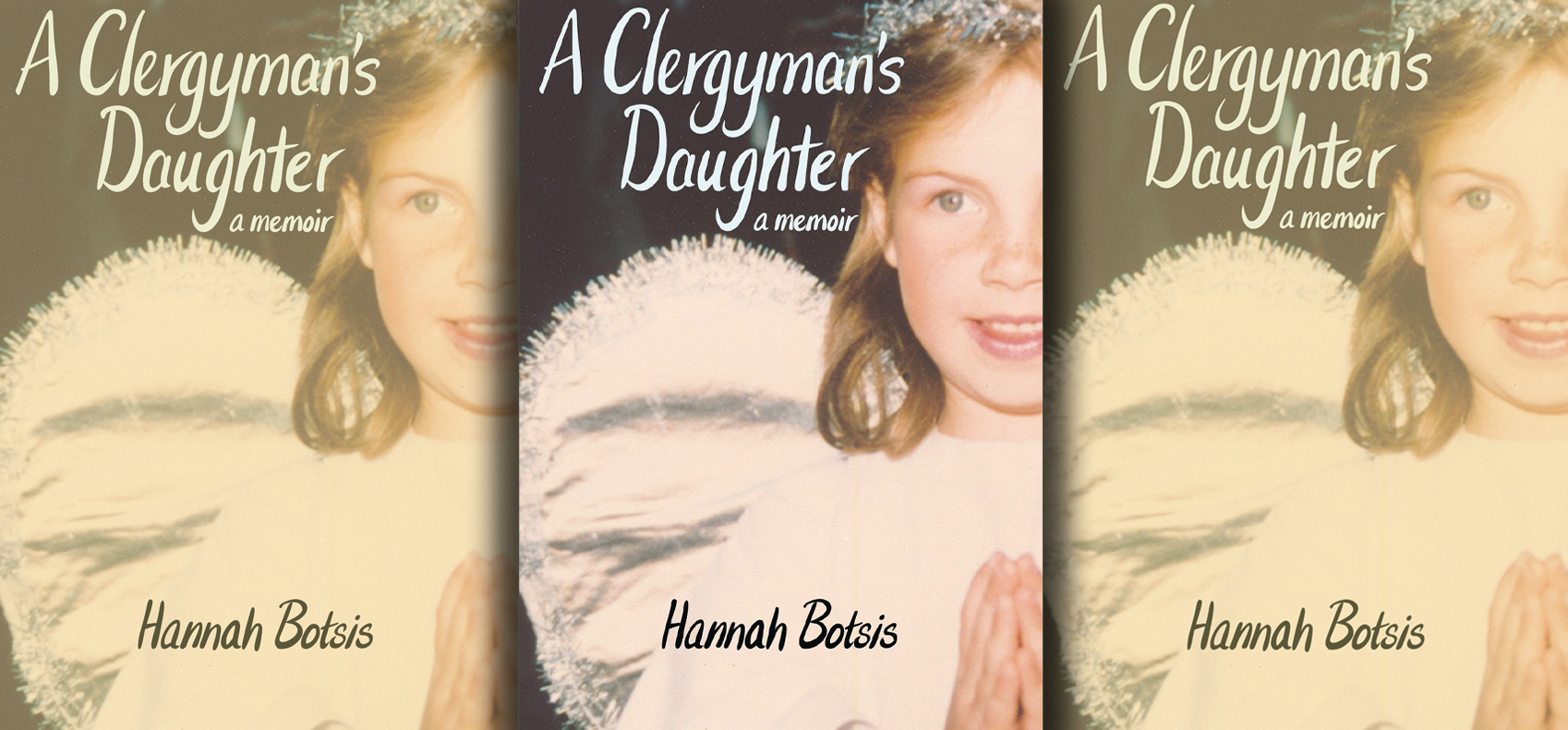

A Clergyman’s Daughter is published by Modjaji Books. It will be available for purchase in November 2025 for a retail price of R330.

A Clergyman's Daughter by Hannah Botsis. (Image: Modjaji Books)

A Clergyman's Daughter by Hannah Botsis. (Image: Modjaji Books)