For too long, strategies for addressing violence against children and violence against women have been siloed, with separate programmes, policies and agencies for implementing protections. However, the South African Child Gauge 2025 has honed in on a simple reality — violence against women and children intersect.

These forms of violence co-occur in the same households, share the same risk factors and drive an intergenerational cycle of harm.

“We know from the evidence… that both forms of violence carry a huge burden, both social as well as economic, and expand to the individual, family [and] community, as well as at societal level,” said Professor Shanaaz Mathews, co-editor of the South African Child Gauge 2025.

“We certainly need a much broader approach [to violence against women and children] than the survivor-centric approach. We need to be integrating a continuum of care from prevention to response into our programmes; we need to think about prevention that… addresses multiple risk factors that drive violence against women and children.”

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Shaneez-Mathews.jpg)

Mathews was speaking at the launch of the South African Child Gauge 2025 at the University of Cape Town (UCT) on Tuesday, 4 November 2025. The gauge is produced annually by the UCT Children’s Institute with the goal of monitoring progress towards realising children’s rights.

The 2025 edition was published in partnership with Unicef South Africa, the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund, the DSI/NRF Centre for Excellence in Human Development at the University of Witwatersrand, the LEGO Foundation, the Standard Bank Tutuwa Community Foundation and the Ford Foundation.

Read more: Childhood in crisis

Intergenerational cycles

According to statistics included in the Child Gauge, 24% of women have experienced physical or sexual violence in their intimate relationships, while 42% of children have experienced some form of maltreatment, including physical, sexual and emotional abuse, or neglect.

“We know that [violence against women and children] occurs in the same household... where children who experience harsh physical punishment also witness domestic violence… They are driven by shared risk factors rooted in gender inequality and supported by social norms that justify men’s use of violence to assert discipline and control, not just over women but also over children,” said Mathews.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Child-Gauge-launch.jpg)

She noted that early exposure to violence was one of the most consistent risk factors for experiencing multiple forms of violence in adulthood and over the life course.

Exposure to violence had a “gendered impact”, she continued, with girls more likely to internalise these experiences, leading to depression, anxiety disorders and physical revictimisation. Boys were more likely to externalise, leading to aggression and risk-taking behaviour, while reducing the ability to form emotional attachments.

“Adopting a trauma-informed approach to reduce the intergenerational cycling of violence is really critical. Importantly, evidence is showing it’s not only about providing programming, but also thinking about how we shift gender norms… Integrating gender-transformative approaches into programming is certainly one of the most successful ways for us to think about shifting social norms that perpetuate both violence against women and children,” said Mathews.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Sindisiwe-Chikunga.jpg)

Sindisiwe Chikunga, Minister in the Presidency for Women, Youth and People with Disabilities, said that each year the Child Gauge showed people that evidence was not only an academic exercise, but the foundation of effective policy, accountability mechanisms and protections for the country’s most vulnerable.

She added that the gauge was a “timely reminder” of the urgency of the government’s mandate to build a South Africa where women and children could be free from fear and harm.

“[The Child Gauge] tells us that violence is rarely confined to one person or generation. The trauma of a mother often spills into a child’s life. The suffering of a child echoes through the household and community, and what happens in our homes and schools is deeply tied to what happens in our economy, our justice system and our social [structures],” said Chikunga.

“This theme therefore challenges all of us as government, civil society, academia [and] the private sector to confront these links, coordinate our responses and ensure that interventions reach families as a whole, rather than as separate cases.”

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Lucy-Jamieson.jpg)

Strategising for change

Lucy Jamieson, co-editor of the South African Child Gauge 2025 and senior researcher at the UCT Children’s Institute, emphasised that “systemic silos” fractured services and failed to interrupt the intergenerational cycle of violence.

Transforming services and mobilising communities needs to involve:

- Health services, which have the potential to intervene early in the life course and prevent violence against women and children at scale.

- Social services, which play a critical role in preventing and responding to intimate partner violence and violence against children by supporting families, addressing root causes and promoting recovery.

- Schools and early learning programmes, which can be powerful catalysts for change by creating safe, respectful and caring environments where children can learn and thrive.

- Communities, as engaging the whole of society, including political, religious and traditional institutions, is essential to challenge and transform social norms linked to violence against women and children.

“Recognising that violence is intersectional, we need to pay attention to the specific needs of vulnerable groups — adolescents, women and children with disabilities, the LGBTQI+ community, and also special attention in our rural communities,” said Jamieson.

Creating an enabling environment for ending violence against women and children required a robust policy space, strong leadership and coordination, adequate financial and human resources, and multisectoral data and information systems to guide service delivery, she continued.

“We see that women and children fall through the cracks because services are provided for one and not the other. There are funding silos that create competition between NGOs who provide services to women and [those] that provide… services to children,” explained Jamieson.

“There are silos in our training and education systems. The referral protocols often are driven by [separate] sectors… We find low levels of trust and limited referrals between sectors. We also see that our data is siloed, and that prevents integrated monitoring and evaluation.”

Jamieson noted that South Africa had an “expansive” range of laws and policies to uphold the rights of women and children. However, she added that the primary challenge was not gaps in the legal framework, but poor implementation.

“We’re not calling for extensive revisions. Rather, we want to see improved accountability for delivery,” she said.

When it came to financing, Jamieson said that studies in South Africa had shown that violence against children alone cost the country an estimated 5% of overall gross domestic product.

The policy brief for the Child Gauge 2025 emphasised that preventing violence against women and children would yield significant returns on investment, enhance human capital and social cohesion, and boost economic development.

“Despite these compelling economic arguments, South Africa is failing to uphold its constitutional and international obligation to fund services to protect women and children from violence and to prevent violence from occurring. Funding remains grossly inadequate and is being steadily eroded by austerity cuts,” said Jamieson.

She advocated for an approach to prevention that included both women and men, while actively challenging and transforming harmful social and gender norms.

“It’s only by breaking these silos and working in a coordinated way that we will be able to break the intergenerational cycle of violence,” said Jamieson. DM

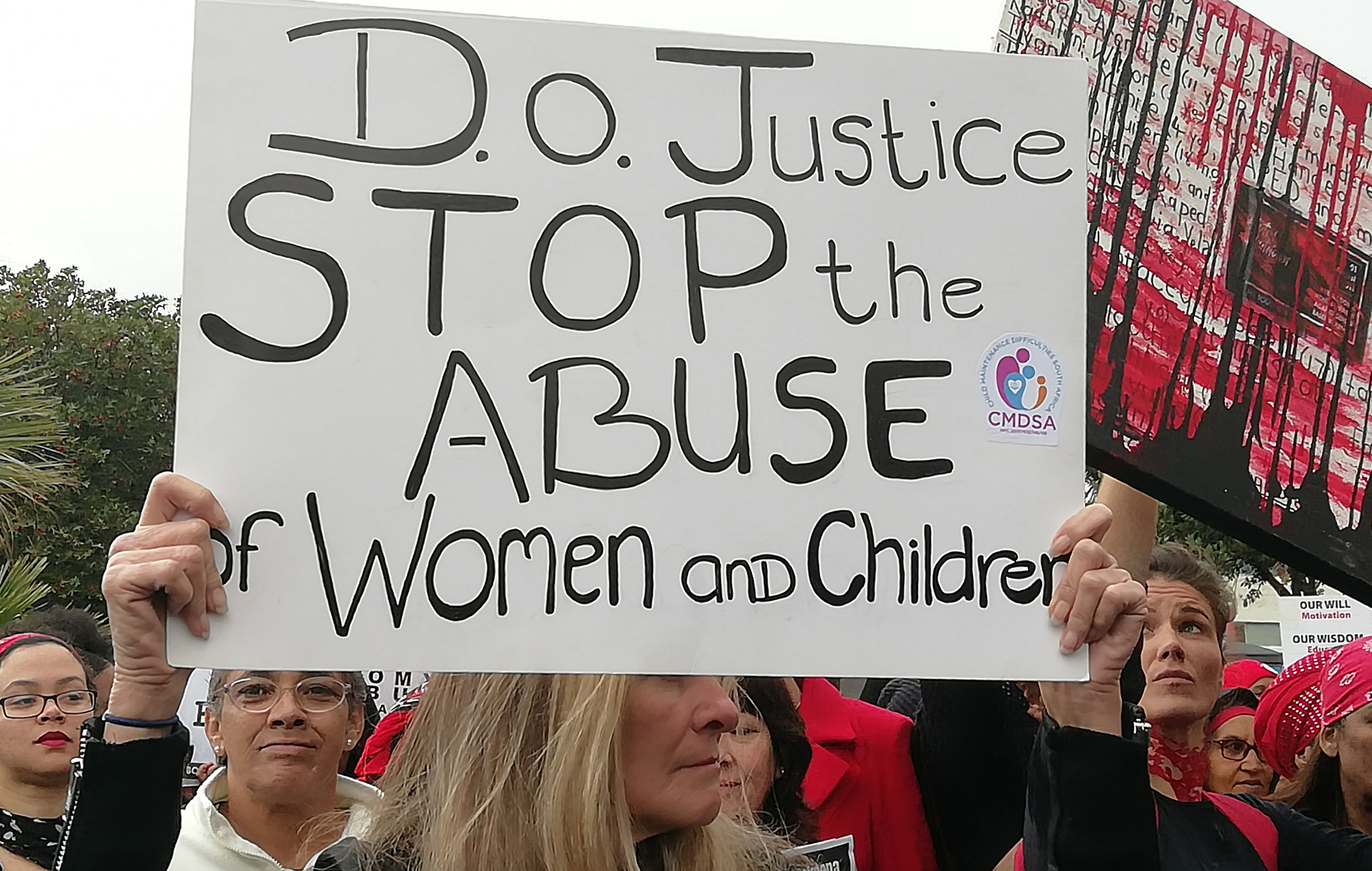

A protester holds a 'stop the abuse' placard during a march in Cape Town. (Photo: Suné Payne)

A protester holds a 'stop the abuse' placard during a march in Cape Town. (Photo: Suné Payne)