The first article in this series, “Sea Point’s broken promises — no place for old locals”, can be accessed here.

“When you say things like ‘spatial apartheid’,” noted Geordin Hill-Lewis, “I think that’s just kind of propaganda language that is no longer rooted in reality.”

Daily Maverick was barely into the third question of our interview session with Cape Town’s mayor, and the exchange — although polite and cordial on the surface — had already become combative. Hill-Lewis said he wasn’t sure whether the phrase was ours or whether it was the language of the co-director of Mother City, the award-winning documentary about the fight for affordable housing in Cape Town, but either way he wanted it known that he didn’t approve.

The film, he told us, was no more and no less than a “tacit endorsement for illegal land occupation”.

As the interview had been scheduled for only 30 minutes, Daily Maverick did not have the time to dig into the concerns and perspectives of Ndifuna Ukwazi and Reclaim the City, the two social activist groups that had featured strongly in Mother City — the very same groups, it turned out, that had been waging an epic battle in South Africa’s courts on behalf of Cape Town’s marginalised.

Had we had more time, we would have pointed out that the allegations of spatial segregation seemed relatively standard across the Cape Flats, a perception that the governing Democratic Alliance had probably entrenched when — a few weeks after the Western Cape Division of the High Court had ruled in favour of the two groups in their bid for affordable housing in Sea Point — they took the matter to the Supreme Court of Appeal.

Still, the long-anticipated final ruling of the Constitutional Court aside, Hill-Lewis did offer us a detailed counter-argument to the allegations of spatial apartheid. Likewise, in stressing the priority of job creation and tourism in his future vision for the city, he countered most of Daily Maverick’s reporting in the first part of this series.

Did he convince us that we were wrong about the role of unfettered development and foreign ownership in the decimation of Cape Town’s local communities? Do we now believe that middle-income earners should stop complaining about how expensive the city is becoming? Is the mayor of Cape Town correct in his assessment that neither the current mayor of Barcelona (Jaume Collboni) nor the likely future mayor of New York (Zohran Mamdani) have much to teach him about how to run a city?

These questions, by our reckoning, have no final “yes” or “no” answers. As Hill-Lewis himself makes clear, running a metropolis of five million or more people is no easy task. But of course, without any real political opposition to speak of in Cape Town, it is the role of civil society and the media to hold the ruling Democratic Alliance to account.

As with all of our Q&As, the interview with Hill-Lewis has been edited for length and clarity.

Kevin Bloom: Thank you for agreeing to the interview, Geordin. Let’s start with your overall reaction to our piece. In the introduction, we stated that the famous restaurants, bars and cafés of old Sea Point are all closing, making way for a development-scape of absentee landlords, micro apartments and short-term rentals. We asked whether this portended the Cape Town of the future, a place where “community” would be a thing of the past. In a private message to me on the day of publication, you noted that you had only one “quibble” with the piece, which we will get to later. But on the whole, you seemed to approve — could you elaborate?

Geordin Hill-Lewis: Look, I definitely think that there’s a lot of development happening in Sea Point. I actually had dinner with my wife there on Friday night, and just looking across the landscape and seeing the number of cranes — I counted six or seven — it’s clear what’s happening. And with that comes, yes, the changing nature of the residential and retail terrain.

I must say, Kevin, that I think that’s entirely normal for very successful cities all around the world. If you look at the changing landscape of Manhattan over the past 50 years, if you look at the changing landscape of central London, of central Paris, even of Eastern cities — you know, Hong Kong or Singapore — the neighbourhoods that are very desirable for people to live in tend to experience pressures for development. And along with that comes changing restaurants, changing grocery stores, and so on.

I still think there are a number of old restaurants that remain. You know, I’m not a resident of Sea Point, I live out in the suburbs, but I’ve been going to Sea Point for years, obviously. I still go to places like Ari’s Souvlaki [ed note — the restaurant closed permanently in December 2023], which has been there forever. Places like Giovannis, or that very authentic Chinese restaurant right at the beginning of Main Road, Hesheng.

Those places have all been there since I was a kid, and I think will continue. Obviously, those restaurants that keep offering the best product, that keep attracting their customers, they will survive and thrive. The others will not, that’s the competitive restaurant trade in Cape Town and elsewhere.

So, you know, I think your piece describes the changing nature of the Sea Point property market. I don’t think there’s necessarily anything untoward, or anything unexpected, or anything unusual in it, if you think about very desirable neighbourhoods in successful cities around the world.

Kevin Bloom: Sure, except that Cape Town, as one of the world’s leading tourist destinations, is often compared to cities like Barcelona, one of the big-ticket destinations in the Global North. But unlike Cape Town, in order to protect the integrity of local communities — and more to the point, in order to ensure that long-term residents can continue to afford a life there — rent control has been a reality in Barcelona for more than 18 months now. Also, to address the housing crisis, Barcelona plans to phase out all short-term rentals by 2028. Does the City of Cape Town see Barcelona, in any way, as an example worth following?

Geordin Hill-Lewis: No.

Kevin Bloom: No, with no elaboration?

Geordin Hill-Lewis: Well, there’s just a fundamental difference in context. Barcelona has 20-million overseas visitors every year. They have got more visitors in their busy month, which is June, than we have in an entire year. Cape Town has 1.5-million visitors in an entire year.

The other huge contextual difference between Barcelona and Cape Town, or Spain and South Africa, is that Spain has single-digit unemployment. South Africa has 36% unemployment. Even in Cape Town, where we have 21%, which is much lower than the rest of the country, it is still far too high — that number would be considered in Europe, or anywhere else, as crisis-level unemployment.

So our primary priority, our first and highest priority, must be getting people in to work and out of unemployment. And tourism is one of the best places in our economy that we can grow jobs. In Cape Town, overseas arrivals have been growing by 7% year-on-year for the past decade. Now imagine if our national economy was growing at 7% — unemployment would be halved, or more than halved. This one tiny section of our economy, overseas arrivals in Cape Town, we dare not mess with that. In fact, we should be encouraging further growth.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Z63_8236-copy.jpg)

And yes, of course, all growth comes with pressures. There’s no such thing as a pressure-free growth scenario. But, the question is, those pressures that come with success, are they better or worse than the pressures that come in our society from widespread poverty and unemployment? And I argue, emphatically, that they are much, much better. So, I really want tourism to grow further. I want to grow that 1.5 million to three million. Because I know that it will put probably another 150,000 people in our city to work.

Kevin Bloom: Fair enough, but speaking of pressures, on the day our piece was published we were contacted by one of the directors of the acclaimed documentary Mother City, who told us that — despite all of nine official invitations — you have so far declined to attend a screening of the film. As you no doubt know, Mother City follows the fight for affordable housing in Cape Town’s “well-located” areas, with social activists demanding that the people who service the tourist economy — from restaurant workers to hotel staff to cleaners — finally be granted housing close to their places of work. In essence, it is a film about spatial apartheid; about the fact that the City of Cape Town seems uninterested in addressing the phenomenon. What are your comments?

Geordin Hill-Lewis: Who contacted you?

Kevin Bloom: It was Pearlie Joubert.

Geordin Hill-Lewis: Okay, well, I’m not sure why Pearlie is saying that, because I have seen the film. I watched the film myself; they sent me a link to it, and I watched it. So I don’t need to attend an official screening in order to watch the film. And the film is a propaganda film. You know, it makes a particular argument from a very particular vantage point, and tries to provide a tacit endorsement for illegal land occupation, which we simply will never endorse.

We have done more in the last three years to release land for social housing in well-located parts of the city than in the 10 years prior to that combined. So we are committed to releasing land for social housing. We’ve got a number of projects. I think the number is now at about 12,000 units at various stages of development. Not all in Sea Point, obviously, but in well-located parts of the city.

So we have greatly accelerated our work in social housing. I’m not sure whether those adjectives are hers or yours — when you say things like “spatial apartheid” and “deliberate exclusion” [ed note — this last phrase was not used in the interview] — but I think that’s just kind of propaganda language that is no longer rooted in reality.

The fact is, it’s very difficult, practically, to make projects work when land is so expensive and you want to get rentals as affordable as possible. It’s really tough. So it’s not just a matter of flipping a switch and saying, now there shall be, by decree, all this cheap accommodation. It takes hard work. And we have undertaken that hard work. And as I say, we have accelerated more of those projects in the last three years than in the 10 years prior to that combined.

Kevin Bloom: Okay, thank you for that. So one of our interviewees for the piece was Bas Zuidberg, the interim chairperson of the Cape Town Collective Ratepayers’ Association. As a foreigner himself, Zuidberg notes that — in his estimation — more than half of the new property owners on the Atlantic Seaboard are probably international investors, who visit Cape Town for a month or two every year and, for the remainder of the time, either leave their properties empty or rent them out short-term. For Zuidberg, aside from removing stock from the long-term rental market, this is one of the factors that hollow out local communities, not only on the Atlantic Seaboard but also across the Deep South. Would you agree with that assessment? From your perspective, what are the upsides to unregulated foreign ownership?

Geordin Hill-Lewis: Well, I just can’t comment on that data. It sounds extremely alarmist. I just don’t have any credible data with which to argue with [Zuidberg], and I’m not sure that he has any credible data in making that statement, it just sounds like an opinion. So do you know on what that is based?

Kevin Bloom: That’s based on his assessment, but there is a graph out there by a reputable property company that’s not far off his number [see below]. I would have assumed that you had more credible data, but I’ve seen the graph and I’ve heard Bas Zuidberg and then, you know, it’s also the experience of people on the street.

Geordin Hill-Lewis: Mm, well, you know, that’s all anecdotal. But look, international buyers who are coming here are mainly competing in the very high end of the market. So they are not hollowing out communities for middle-income Capetonians, they are not competing in the same property market at all. They are competing in the absolute top, top niche of the market, properties in general close to R10-million and well above that.

Again, I think that there is this simplistic analysis, and I hope that you are not falling into this as well, Kevin, that says because someone is coming here to buy a R25-million apartment, they are hollowing out a community. That is the absolute tiny pinprick niche of the Cape Town property market. This is a city of five million people, and my focus is on how we actually generate more and more resources so we can do more to assist those far outside of that pinprick niche, who need much better services and more help.

And so, for me, it’s actually a positive when we see people coming to buy very expensive properties here, because it allows us — and we have a very strong system of cross-subsidisation in Cape Town — so it allows us to deploy our resources, very deliberately and unapologetically, into poorer communities, as we are doing. And that was my one big quibble with your piece, which we must please come to.

Kevin Bloom: Sure, we will come to that in a few minutes. But first I want to return to the issue of the short-term rental market. When you look at new developments, like the one that knocked down my favourite local pub, there are tax breaks [see bottom of hyperlinked page] for investors who want to buy five apartments or more. The dozens of micro-apartments in just that one building, at 25 square metres of floor space, are not suitable for long-term living. I would be very surprised if a substantial percentage of the bulk buyers in that development weren’t foreign, as in, people who can access our cheap currency to enter the Airbnb market. So this is also how a local community is hollowed out, is it not?

Geordin Hill-Lewis: Those tax breaks have nothing to do with the City, you will have to check with SARS. But on the short-term rental question, there is one thing that I do agree with. The fact is, if you are buying five apartments and letting them out full time, whether through Airbnb or whoever, you are running a hotel. And there I fully agree with those who have said that there must be an equal playing field between those businesses and hotel businesses.

And so we are doing an exercise right now, it’s under way, and several hundred [properties] have already been transferred onto the commercial tariff — so it’s a much higher level of city charges for commercial businesses than for residential homes. Meaning, yes, we are going to make sure that there is an equal playing field from a City perspective. Obviously, from a SARS perspective, they are still paying different rates of tax, if they haven’t declared that they are actually running a business. And of course we are happy to share our data with SARS, once we have completed our exercise.

Again, I just want to stress that I don’t think banning short-term rentals will work. I actually had this debate with the mayor of Barcelona. If you ban short-term rentals, where are your tourists going to stay? We have 1,5 million tourists who must be accommodated, and we really want that number to grow.

So speaking about the destruction of your favourite pub, all you will have is a further construction boom. New hotels would have to be built to accommodate all those tourists. In one way or another, you are still going to need to have a bed somewhere. And whether that’s in a hotel or in an apartment, they take up similar amounts of space in your city. The point I’m making is that they need to be paying similar rates of tax.

Kevin Bloom: Okay, thank you for that clarification from the City’s perspective. So your one major issue with our piece, you said, was that by placing “a small portion” of fixed services charges on property values, the City of Cape Town is by definition “trying to protect” low- and middle-income earners. You disagreed vehemently with our observation that rate increases have been placing an “unbearable burden” on this class of homeowner in the wealthier, sought-after suburbs. But still, our research shows that many lower- and middle-income ratepayers in these suburbs — particularly retirees in Sea Point and Green Point — have been getting desperate. After publication, in fact, a number of long-term residents of these suburbs let us know that they had been forced to relocate. What are we missing?

Geordin Hill-Lewis: Yes, so, let’s just go through this step by step. We run a very redistributive system where, again, quite unapologetically and deliberately, we redirect a huge proportion of our resources into basic infrastructure in rapidly growing, poorer communities. And so when we design a budget, the question is how we share the load among all the residents in the city. In our budget, we assign 18% of a homeowner’s rates to fixed charges, with 82% assigned to variable, consumption-based charges. So to base the fixed charges on property values means that, by definition, people in lower-income areas with lower property values are protected.

Now, there’s no perfect model when you are trying to design a tariff. Obviously, when you design a tariff based on property values, there are going to be some people who are negatively affected, like those with a high property value but low income. Again, property value is not a perfect proxy for income.

And so we asked what we could do to protect those people in particular, and mostly they are pensioners. We decided to raise our pensioner income level from R18,000 two years ago to R27,000 this year — a massive raise, by far the most inclusive income threshold in South Africa, the next best is Johannesburg at R21,000. So that means any pensioner earning less than R27,000 can have all of the increases rebated back, it won’t affect them.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Z63_7664-copy.jpg)

Of course, for those pensioners earning more than R27,000 a month, you have to ask two questions. First, do they require a state subsidy? Second, with 82% of their bill consumption-based, don’t they still have a good measure of control?

Overall, although difficult choices have to be made when designing a budget for five million people, I think it cannot be disputed that the huge majority of low-income earners in Cape Town have been protected.

Kevin Bloom: Perhaps that’s true, or perhaps it requires more reporting. Either way, as a final question, there is an international phenomenon that’s surely applicable to the City of Cape Town.

About a month ago, as a way in to our question, the New York Times ran a piece about “wealthy developers” who had been meeting to “plot the defeat” of Zohran Mamdani, the Democratic Party nominee for New York mayor. Mamdani, as I’m sure you’re aware, is running on the ticket of making New York affordable again, through policies such as rent freezes, free buses and City-run grocery stores. His agenda to tackle the housing crisis is perceived, perhaps correctly, as a big threat to New York’s investor class.

Would you agree that a similar dynamic exists in Cape Town, where a select group of developers and investors are making out like bandits while exorbitant living costs are foisted onto everyone else? Also, you happen to be in the fortunate position of having no real political competition in Cape Town. But going forward, would you align yourself more with Mamdani’s position than with the position of Andrew Cuomo, his pro-investor class adversary?

Geordin Hill-Lewis: I think rent controls are one of the fastest ways to destroy a city, other than by war. Rent controls will guarantee that city buildings turn into slums, because landlords will simply stop looking after them. And there is a huge international literature on the utterly disastrous impact of things like rent control. So I think it’s a really, really bad policy, and I would never support it, because it completely removes the incentive to look after your property asset.

Just look at downtown Port Elizabeth [ed note — renamed Gqeberha], where the huge majority of properties are owned by a handful of owners — because the City has been in such steep decline, they cannot achieve any desirable rentals from there, and therefore have just stopped looking after those buildings. And then you get into this self-reinforcing terrible cycle, like you also see in downtown Johannesburg, where the whole city very quickly falls apart.

So, again, these issues that you are bringing up are the pressure of success, and they are better than the pressures of failure. But they are pressures nevertheless. I don’t like to demonise entrepreneurs. You know, I think that by definition, prices would be much higher if there was no new supply coming onto the market. That’s a mathematical fact, an economic fact.

Of course there are, as with everything, developers who get up to no good, there are bad corporate citizens. And the City has very rigorous and strict processes that deal with them, including going to get demolition orders in the court. But in general, these are an entrepreneurial class of people who are providing for a demand in the market, who are helping somewhat to ameliorate the pressures on prices by meeting the supply.

They are also providing a huge number of jobs. You know, the Presidency put out a report showing that 17% of all construction in South Africa is currently taking place in Cape Town. If you consider that Cape Town only accounts for 9% of South Africa’s GDP, that means that we are punching at nearly double our weight in job creation in the construction industry. That, I think, is something to celebrate — because again, Kevin, I really want to stress that our most important priority in South Africa is getting people out of unemployment and in to work. DM

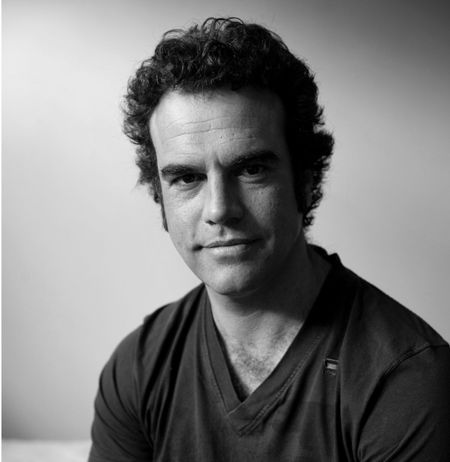

Illustrative image | Sea Point Main Road in front of an apartment complex construction site, 9 September 2025. (Photo: David Harrison) | Executive Mayor of Cape Town, Geordin-Hill Lewis. (Photo: Gallo Images / Die Burger / Theo Jeptha)

Illustrative image | Sea Point Main Road in front of an apartment complex construction site, 9 September 2025. (Photo: David Harrison) | Executive Mayor of Cape Town, Geordin-Hill Lewis. (Photo: Gallo Images / Die Burger / Theo Jeptha)