From skeletal remains found beneath a swimming pool to a child abducted outside her home, Engelbrecht reopens files, re-examines evidence and shares material not made public before. Here is an excerpt.

***

The phrase ‘cold case’ often instils a sense of hopelessness in people, especially in South Africa. I’ve discovered something interesting about these types of cases, though. Time passing can reduce the possibility of a case being solved in terms of physical evidence being missed and a perpetrator having the opportunity to cover their tracks. On the flip side, though, I’ve found that the passage of time can also be a positive factor.

The old adage goes that when a murder happens or someone goes missing under suspicious circumstances, ‘someone always knows something’. That is absolutely true. Apart from the perpetrator, there is often at least one other person who has the information investigators need. The type of person who is capable of murdering or causing someone to go missing is typically a pretty scary individual. Those who have information about the case are often either involved with that person in a criminal sense, or they are close to them and probably afraid of them. The power of time passing in a cold case is that circumstances change. Relationships end, people move on, and the intense fear that keeps them quiet in the early days of a crime may have evaporated.

In addition, a perpetrator will be careful not to tell anyone what they’ve done immediately after the crime. As time goes by, though, and it looks like everyone has forgotten, they might start sharing odds and ends of information with others.

The information required to solve most cold cases sits in the head of at least one individual, and often more. One or two decades later, it’s my job to find that person by telling the story, humanising the victim and encouraging the flow of that information. It’s my listeners’ and readers’ job to share each story as widely as possible to ensure it finds the person with the key to solving the case. If this sounds a little ‘out there’, I’ll quote directly from the first message I received with a lead in a cold case:

‘I’ve had this information for a long time. I think over the years I have convinced myself that it didn’t matter any more, or maybe it wouldn’t make a difference. But then I heard your podcast and I realised that as much as I had tried to pretend this wasn’t real, it was. She was a human being with a family, and even if this doesn’t help I can’t keep it to myself any more.’

This was in relation to a missing person case you’ll read about later in this book, but the same thing has happened with many other cases. So, yes, time can be damaging to investigations but it can also be exactly what’s needed to solve them.

With 27,621 murders in a year, SAPS detectives will not be looking for more to investigate. So, the cases that end up in the ‘closed as undetected’ category are unlikely to be pulled out of that filing cabinet unless someone is instructed to reinvestigate them. This is one of the main reasons cold cases aren’t often solved in South Africa. Recently, though, we’ve seen the SAPS attempt to task specific detectives with investigating only cold cases. In 2023, I covered a story which perfectly exemplifies how a cold case can be resolved even decades after the crime.

***

It’s 1985 in Fish Hoek. The coastal town is on False Bay at the eastern end of a valley that bisects the southern Cape Peninsula. Although the Western Cape is now known as a province that enjoys its liquor, especially some of the vintages from its array of wine estates, at the time Fish Hoek was a dry town. When the land on which it stands was first made available, the title holder had one condition: alcohol should never be sold there. Unbelievably, that instruction stuck for more than a century, long after the title holder’s death. Although restaurants and hotels eventually started serving alcohol for on-site consumption, the town had no off-site establishments until 2019, when Pick n Pay opened its first bottle store.

In 1985, though, when 80-year-old Norah Coram lived in 2nd Crescent, Fish Hoek was still very much dry. If anyone wanted alcohol, they’d have to go elsewhere.

Norah was a British citizen who had lived in South Africa for most of her life. Despite her advancing years, her nephew, Andrew Kavanagh, says she was full of energy and vitality. One of her favourite pastimes was watching cricket and she would often hop on the train and head to Newlands to enjoy a match. She also volunteered with the local cub scout organisation and attended church every Sunday without fail. Norah had lived on her own for a long time, but she quite enjoyed her independence. She was still strong enough to do most things herself, and when she needed an extra pair of hands she’d wait for her nephew to visit or hire help. She had occasionally employed a young man to help with maintenance around the house and garden. Tommy (not his real name) lived in Ocean View, an area established in 1968 under the Group Areas Act. At the time, it had been intended to house predominantly coloured people who had been forcibly removed from their homes in Simon’s Town, Noordhoek, Red Hill and Glencairn as part of the apartheid government’s efforts to create racially distinct living areas.

In early July 1985, Tommy arrived unexpectedly at Norah’s house. He called out to her from the street and she went out to see what he wanted. Ocean View is only about 12 minutes’ drive from Fish Hoek, but Tommy would probably have walked for about an hour and a half to get to Norah’s home. He told her that he didn’t have any food at home and asked if she needed any chores done in exchange for something to eat. Norah had no work for Tommy, but feeling sorry for the young man, she invited him in and said she would make him some food.

Once Tommy was inside, things went badly wrong. While Norah was pottering around the kitchen making sandwiches, the young man attacked her. He punched her several times before tying her up and locking her in the bathroom.

Tommy then ransacked Norah’s home, taking several items of value. He probably believed he had killed the woman; he knew she could identify him and would not have left her alive on purpose. But while Norah was badly injured from the assault and unable to move due to the tight bindings around her hands and feet, she was alive.

The elderly woman listened as Tommy ransacked her house, and eventually she heard the front door close and the distinctive sound of the garden gate squeaking. For the next few hours, Norah shouted with all her might in an attempt to get her neighbours’ attention. July is a particularly cold winter month in South Africa and she was lying on the bare bathroom floor. As the sun went down, the temperature dropped and Norah began to shiver. The next morning, she heard sounds outside her bathroom window as her neighbours prepared to leave their house, and with the last of her strength she shouted for help.

Eventually, 36 hours after her ordeal had begun, her neighbour found Norah on the bathroom floor and called the police and an ambulance. By the time Norah arrived at hospital she was extremely dehydrated and in a precarious condition. Her assault injuries had caused severe swelling, and her hands and feet were swollen from being bound for so long. Doctors admitted her to the intensive care unit and the hospital notified her family.

A case of assault with intent to do grievous bodily harm, as well as housebreaking, was opened with Fish Hoek police. Within a few days, Norah was able to provide a full statement about what had happened. She even identified the perpetrator as the young man who had worked for her. When Norah’s nephew Andrew heard what had happened to his aunt, he rushed to the hospital. He spent the next few weeks visiting her as she recovered, until he was called up for national service in August 1985.

As is often the case as we age, even if we are relatively healthy, a serious injury or major physical trauma can take a long time to heal. Sometimes, additional ailments can result from the initial injury, especially if it is accompanied by emotional trauma or the body is run down for any reason. In Norah’s case, she had spent 36 hours tied up in the dead of winter on a cold bathroom floor. She’d also been assaulted and experienced significant emotional trauma. As a result of all of this, she developed pneumonia in hospital and in September 1985, while her nephew Andrew was undergoing basic training in the army, he received news that his aunt had passed away.

The charge of assault with intent to do grievous bodily harm was pushed up to murder. But despite all the information Norah had provided about her assailant, Tommy could not be found. Police questioned people in Ocean View, but under apartheid rule the police were a ‘force’ used against the majority of South Africans, not a ‘service’ for all. On the whole, people of colour had a deep fear of and hatred for police officers, who were instrumental in enforcing government policies that kept them segregated and disenfranchised. Tommy seemed to have left the area, but if he was there, no one was talking.

Sometimes we forget how far we have come in terms of technology in such a short space of time. Almost all the investigative technology we take for granted today did not exist in 1985. There was no DNA testing and people could quite easily live without leaving any digital trace. And that is exactly what Tommy managed to do.

After Norah was laid to rest, her family continued to hold out the hope that Tommy would be apprehended, but with each year that hope began to fade. The docket for Norah’s murder remained at Fish Hoek police station but it was soon covered in dust in a filing cabinet – closed as undetected. South Africa went through immense changes in the decades that followed, and the police service changed too. Detectives came and went and occasionally someone would look at cold cases, but the murder of an 80-year-old woman never got much attention. Until 34 years later when a new officer started work at the police station.

Warrant Officer Detective Jeremy Marten was transferred to Fish Hoek in early 2019. His mandate was to track down wanted suspects and investigate cold cases dating back as far as he could go.

In 1985, when Tommy went on the run, besides putting out wanted posters and asking the media to write about the case, the police had few other options. There was no social media and even the mainstream media didn’t have nearly the reach it does now. In 2019, though, Marten had a wealth of information at his fingertips. He didn’t even need to leave his desk to restart the investigation into the murder of Norah Coram.

With the name of the offender from her statement, Marten simply searched the databases he had access to. There was no question about who had committed the crime. Norah had identified her killer and her 34-year-old statement meant she could still speak from the grave. Marten knew that a trial in a case so old could be difficult, but he was willing to give it a try.

Within a few hours, Marten found the man he was looking for. Tommy had come full circle. His most recent registered address was back in Ocean View. The detective decided he would start with a gentle approach. Tommy would not be expecting him, although it was entirely possible he had committed other crimes since Norah’s murder and may be wary of the police. If he had, it could play into Marten’s favour because he might just confess to other unsolved crimes. Even though Marten didn’t arrive at Tommy’s address with flashing blue lights or sirens, the visit did not go as he hoped. Instead of taking his suspect to the police station for questioning, he drove off with a heavy heart after being told that Tommy had passed away. He had died at about the same time that Marten had arrived in Fish Hoek – so recently that his profile hadn’t yet been flagged as deceased.

After chatting with Tommy’s family, Marten confirmed that he was the same man who had lived in Ocean View and worked for Norah Coram 34 years earlier. He’d been in his early fifties when he died, but his family said he had occasionally spoken about his previous employer – the one who had been murdered. His retellings of the story had seemingly been free of emotion. Those who had heard it from Tommy said there had been no indication that he had any more involvement than having once worked for the woman. Details of any other criminal activity the man may have been involved in have never been released.

Although Marten is certain that Tommy was Norah Coram’s killer, he cannot put a dead man on trial, so from a legal perspective he remains innocent. From a case perspective, Marten has identified the perpetrator and Norah’s murder is now marked as ‘closed as detected’ (but not prosecutable).

Norah’s nephew Andrew recalls being shocked when Fish Hoek police contacted him in 2019. He had regularly thought fondly of his aunt and felt sad that her murderer had never been brought to justice. At the same time, he believed there was no chance the case would be resolved after so much time. When Marten told him he had found the man but he was already deceased, he felt as if that chapter of his family’s history was finally closed.

Certainly, justice and a guilty verdict would have been preferable, but this resolution was more than Andrew had ever dreamed of – and he knew it was more than many families of murder victims would ever receive. DM

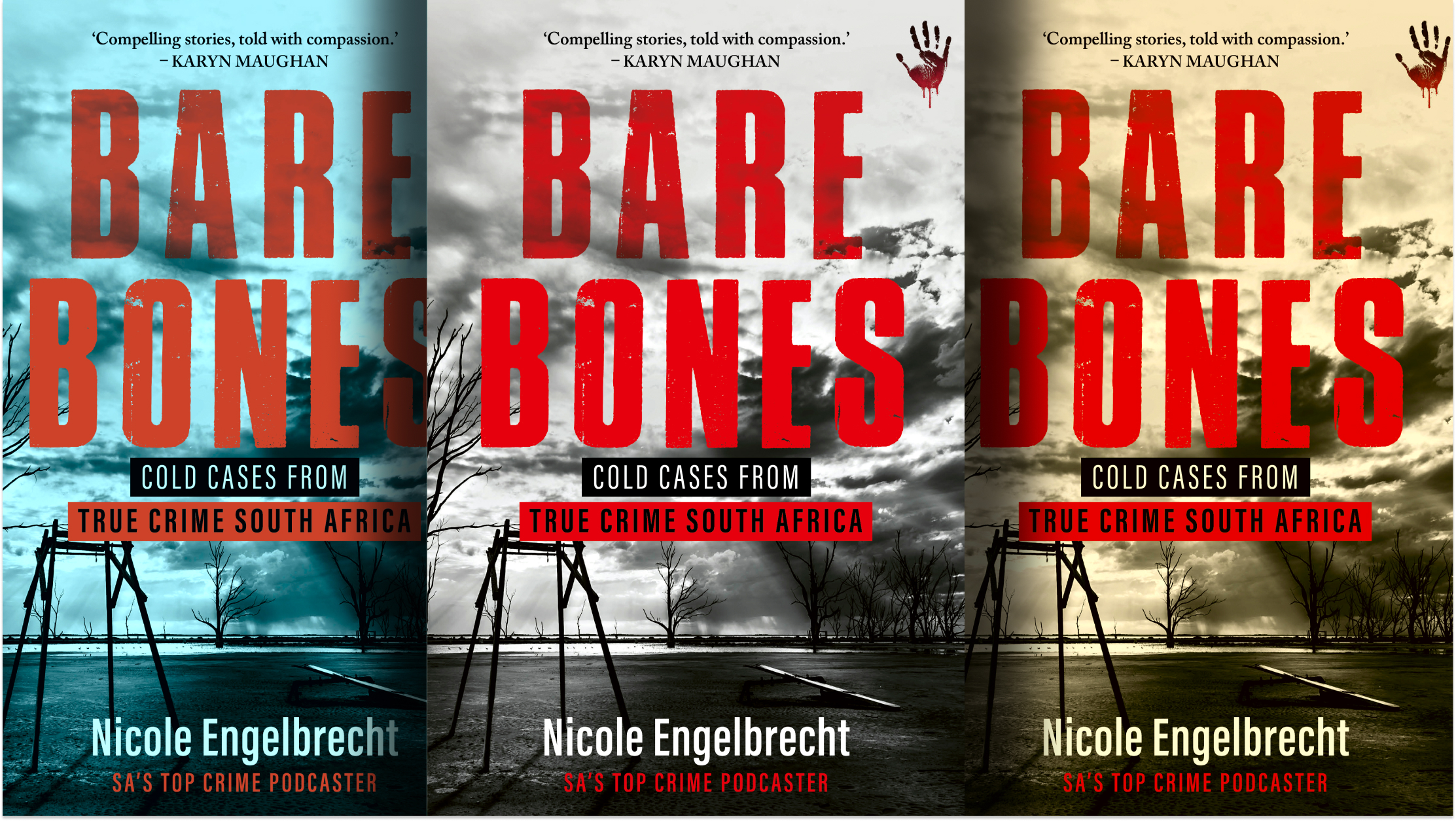

Bare Bones is published by Jonathan Ball Publishers. The book was released in September 2025 and is available in bookshops around the country.