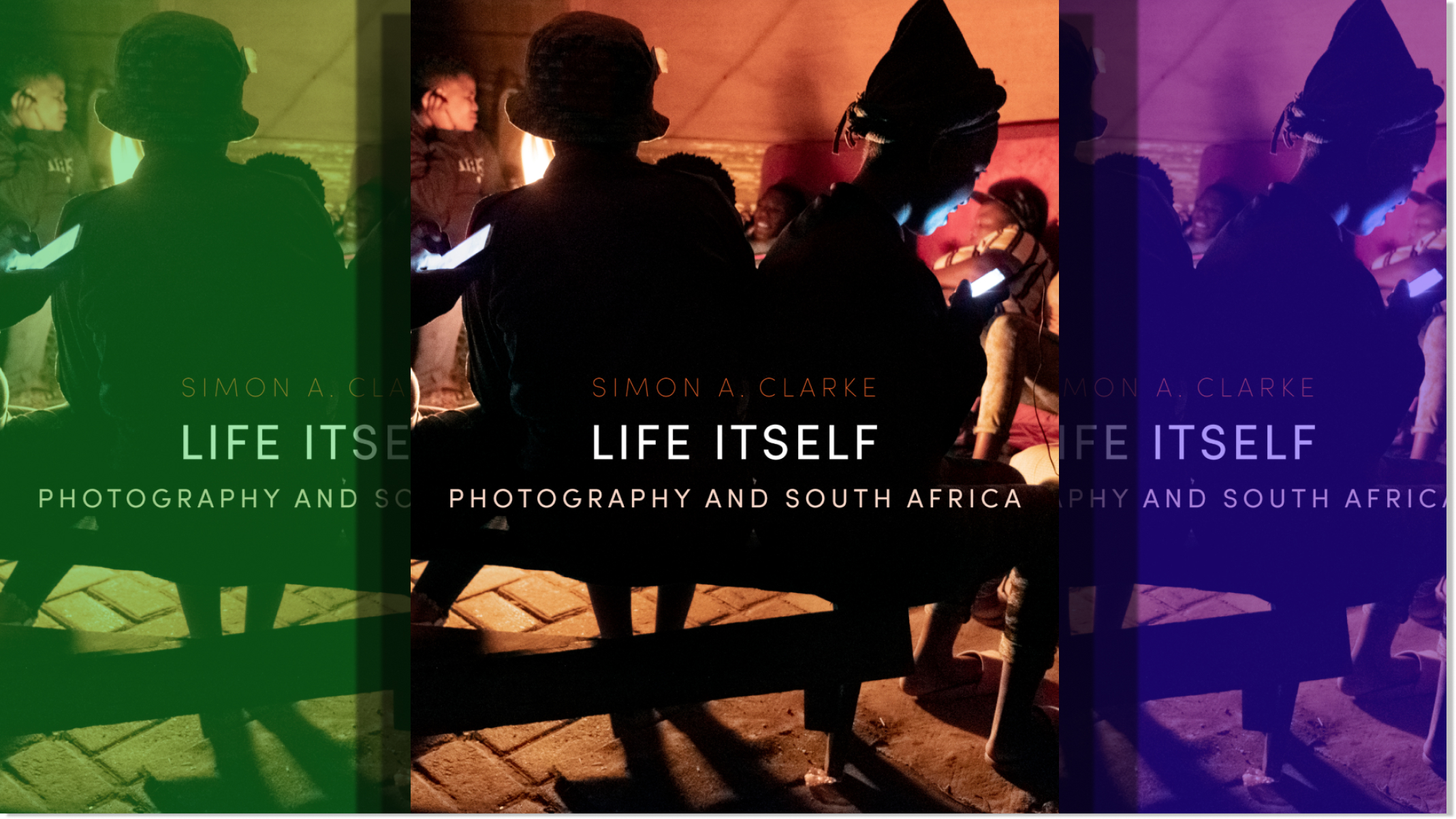

Falmouth lecturer Dr Simon A Clarke has turned years of research into a new book, Life Itself: Photography and South Africa, a visual history tracing the country’s journey from colonialism to democracy.

“My inspiration came from a variety of experiences and moments,” Clarke says. “Louis Mwaniki set me on a track of inquiry into African art… and a chance meeting with South African photographer Roger Ballen in Paris aroused my curiosity in South African photography.”

Read an excerpt below.

***

Photographic Situations: Concepts of Legacies and Contemporary Realities, 1994-2020

Nelson Mandela signed into law the Constitution of South Africa at Sharpeville in 1996. Despite these democratic principles, the nation faced societal challenges that ranged from a problematic education system to extreme numbers of marginalised people. Migration and urbanisation led to inadequate housing, while crime, violence and rising unemployment were growing causes for concern.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/117_-Weinberg-Mandela-votes-.jpg)

Remarkably, Mandela established a stable government and approved the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to reconcile apartheid divisions and uncover human rights abuses. In this post-apartheid setting, Erin Haney identified photography’s potential beyond the documentary imperative, specifically in relation to concept, subject and meaning.

She notes:

There has not been a turning away from documentary photography so much as an acceptance of other genres into the spotlight. While political engagement threads through much contemporary work, photographers grapple with the personal, autobiographical and conceptual themes, the politics of identity, gender and sexuality, present-day economic realities and the matter of personal and social memory.

In essence, photography continued to be a vital form of visual communication with social, cultural and political agency, with the genre of art photography expanding the field across a wide range of themes from legacy to contemporary reality.

Jodi Bieber, in her book Between Dogs and Wolves: Growing up with South Africa (2006), recorded the societal frailties in the toughest urban neighbourhoods and townships in Johannesburg.

From 1994, for more than a decade, Bieber documented life in these communities, from the white working-class Afrikaners in Vrededorp to gangsters in the economically deprived “coloured township” of Westbury. She outlines some of the problems within the communities: it is a place “where gangs rule, where children live with HIV/Aids, and where prostitutes vary the rates of their work depending on the colour of their clients.” She became acutely aware of the harsh realities that confronted her, the premature loss of innocence imposed by these brutal environments and a need to survive. In 1995, she met teenager David Jakobie in Vrededorp, a neighbourhood that had once received support from the National Party during apartheid, but now, in a post-apartheid environment, its residents were left to experience life on the edge. Bieber comments:

Many of the people I met through [Jakobie] had little to do. They smoked mandrax and crack cocaine, and involved themselves in crime… David’s philosophy was ‘why worry about tomorrow. I live for now. If I die I die. I enjoy life whilst I can. A coward dies a thousand deaths. A soldier dies only once.’

Jakobie’s obsession with the notorious Fast Guns gang in the economically depressed “coloured township” of Westbury was where Bieber turned her attention next.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Bieber.png)

She did not want to glamorise gangster culture in the township because in 1996 the media had run stories on gangster deaths in Johannesburg. Engaging with this anti-media community required Bieber to spend time nurturing a rapport of trust. So, putting personal prejudices aside, she adopted an inclusive approach, providing gang members with pictures to illustrate her working process and respecting their views in the final edit.

Reflecting on this experience, she comments: “At times it was confusing. An individual who has murdered and raped can still have wit and charm, and despite knowing what they had done I could find myself becoming fond of them.”

Chris Ledochowski’s picture “Shopfront, Bra Z’s Photographic Studio, Nyanga, 1996” records a shanty-town shop with hand-painted signage. The moment captured seems to illustrate the true democracy of photography, and the spirit of enterprise in adversity within one of the oldest and poorest townships on the Cape Flats.

The intensity of light and saturated colour in the cartoon-styled sign, toy cars and geranium plant are reminiscent of William Eggleston’s pictures from the American South in the 1970s – specifically those focused on details from everyday life. Furthermore, one might identify similarities with Walker Evans’s American Photographs (1938), for example, his photography studio, barber’s shop and roadside shoeshine-stand pictures.

The topography of certain kinds of landscape have acquired symbolic and spiritual potency, such as in ancient cave- and rock-painting sites. This phenomenon applies to the subterranean Motouleng Caves, a place of beating drums, formed by a rock fall in a limestone mountain near the Lesotho border. The caves’ spiritual attributes moved Santu Mofokeng to photograph this site.

His poignant images record a visit with his brother, Ishmael, who was ill with Aids and had declined expensive medical treatment to instead follow a preferred spiritual experience. The caves are a place where religious leaders, healers and their followers gather for worship, consultation and healing.

Afterwards, the pictures formed part of the expansive photography essay Chasing Shadows (1996-2014), which alludes to the elusiveness of spirituality and Mokofeng’s own difficulties during his brother’s illness.

As Mandela’s presidency drew to a close, democracy had a foothold, although racism persisted and corruption was a growing problem. Despite these challenges, Mandela was clear: “The judiciary made no one, not even the president, above the law.”

Thabo Mbeki succeeded Mandela in 1999. Lynn Berat notes: “By the time Mandela left office, he had become a secular saint. After all, against what seemed like impossible odds, he had given the world the miracle of the New South Africa, vibrant, democratic and determined to overcome its tragic past.”

In this social milieu some photography essays straddled the 1994 elections, located between apartheid and post-apartheid histories. This occurs in the project Blood Relatives (1997) by Cedric Nunn, which began as a personal response to the term “coloured”, used by the apartheid government to describe mixed-race nationals.

In his photograph “The Wedding of Deborah Eksteen and Noel Norris, Margate, KwaZulu Natal” Nunn records the poignant moment when his newly married niece, Deborah Eksteen, and her husband, Noel Norris, visited the graveside of her father, Peter, who had died a couple of months earlier.

After deliberating whether to go ahead with the wedding because the family needed to grieve, they proceeded, dedicating it to the memory of Peter. It was held in the church where he was buried, located in a community where Nunn’s family originates and have lived for four generations.

While a personal subject, Nunn could see its universal significance in relation to cyclical themes of death and the continuity of life. Within the picture, elements seem to coalesce to represent Nunn’s broader vision: landscape and environment, social documentary discourse, subtle aesthetic detail and camera craft. Moreover, at an emotive level, the photograph seems to transcend the moment and probe into the observer’s own psyche and perceptions of being. DM

Life Itself: Photography and South Africa is published by Reaktion, retailing at R695.