In It Always Seems Impossible, James Urdang recounts his remarkable transformation from a rebellious youth with ADHD and dyslexia into the founder of Education Africa, an organisation that has changed thousands of lives.

This memoir is both an insider’s account of the struggles behind social impact work and a testament to South Africa’s ongoing pursuit of justice. With endorsements from global figures and a foreword by the Nelson Mandela Foundation, it stands as an inspiring call to action for future changemakers. Read an excerpt below.

***

A letter from the Lord

South Africa’s covert security forces would not be as gentle in their attempts to handle the burden of Peter Hain, public enemy number one. In 1972, he received a letter bomb in the post but the wiring was faulty and it failed to explode. Three years later, when he was the leader of the youth wing of England’s Liberal Party, Hain was charged with robbing a bank, largely on the testimony of three schoolboys who had chased the alleged thief. It turned out to be a case of mistaken identity, with the suspected involvement of South Africa’s notorious Bureau of State Security (BOSS), a high-budget, secretive government intelligence agency. Peter was swiftly acquitted.

His subsequent career in parliamentary politics and government in the UK has been long and storied, including stints as Europe Minister, Foreign Minister and Energy Minister, Leader of the House of Commons, and Secretary of State for Wales and Northern Ireland. He was made a life peer in 2015.

In all those years, Hain lost none of his zeal to see justice and good governance prevail in his former homeland. Having stood on the frontline of the battle against the apartheid state, he was equally fearless in his fight against State Capture.

The principal actors in this drama were the Gupta brothers, Atul, Rajesh and Ajay, who amassed a vast fortune through contracts with state-owned enterprises after moving from India to South Africa in 1993. But it was the supporting actors who caught the eye of Lord Hain.

In October 2017, investigating the possible involvement of British-owned entities in facilitating State Capture, he told the House of Lords that two UK banks may have been implicated in the movement of up to £400-million of illicit funds from South Africa. The money had passed through Hong Kong and Dubai, where both banks had a significant presence.

In an open letter to the chancellor of the exchequer in the UK, Lord Hain made his suspicions even clearer. “I have deep concerns and questions around the complicity, whether witting or unwitting, of UK global financial institutions in the Gupta/Zuma transnational criminal network,” he wrote. Referring to the two banks, he went on to say, “Experts I have talked to cannot see how they will not have been exposed to this network.”

I was listening to the radio while driving home from work one day, when I heard Lord Hain being interviewed on the matter. I remember thinking, Peter Hain? That Peter Hain? Lord Peter Hain? Then four little letters rose above the noise of the traffic, each landing like a punch to the gut: “HSBC”.

More than four years had passed since the so-called “full and final” settlement, yet the wounds felt fresh. We hadn’t been taken over by a triumvirate of conniving siblings, nor had we been turned into a laundry for dirty money. But on a small scale, a human scale, our world had been turned upside down. We, too, had been captured.

I heard that Lord Hain had based his concerns about HSBC and Standard Chartered on intelligence received from whistleblowers. Well, I had a whistle, and I was ready to blow it.

At home, I began searching online for “Lord Peter Hain”. I found him on the website of the UK parliament, where his official portrait, set against a grey background, reveals a man dressed for public service: charcoal suit, diagonally striped tie, dazzling white shirt and the half-smile of someone who wants to get this business over with and get back to work. I found his office phone number and email, too.

Forensic investigation

I couldn’t get hold of him by phone, so I emailed to say I had some information about HSBC that might interest him. I attached the document titled “Education Africa: Forensic investigation, high-level synopsis of findings” compiled by Werksmans Attorneys after HSBC’s attempted hostile takeover.

Lord Hain called me at home the next day, his interest piqued by this hitherto unheralded subplot in the saga of HSBC. He had been through the synopsis and was keen to know more.

We agreed to meet when he was next in Johannesburg, at a venue with a special meaning for us both: the Centre for Memory at the Nelson Mandela Foundation in Houghton. The name suggests a space of solitude and quiet contemplation, but to visit here is to hear again that husky baritone, so quick to laughter, and to feel again the sway and shuffle, immortalised in the life-size bronze of a man who held the power to move even when he was standing still. Here, memory is a living thing.

When Peter Hain was a student activist, he campaigned in public for Mandela’s release. In the democratic South Africa, he became Mandela’s friend: “Ah Peter, return of the prodigal son!” Mandela had said, when Hain returned to the country of his birth as Britain’s minister of state for Africa in 2000.

The prodigal son went on to write a biography of his friend in 2010: Mandela: His Essential Life. He tells a story that illustrates two of Mandela’s essential qualities: his playful sense of humour and his abiding concern for the welfare of other people. When he heard that Hain’s mother, Adelaine, had been feeling unwell, he called and insisted, “I must speak to her.” She answered from her bed. “Hello, Nelson Mandela here,” said the caller. “Do you remember me?”

I sat on a cushioned bench with Lord Hain, sharing reminiscences of Mandela before moving to our matter of mutual interest. He had become an expert on HSBC’s alleged complicity in State Capture, and his parliamentary privilege allowed him to call it criminal without fear of legal consequences. But there was substance to the allegations too, as proved by the conditional R15-million fine imposed on HSBC by the South African Reserve Bank in 2018 for weaknesses in processes that inhibited the bank from “proactively detecting potential money laundering and the financing of terrorism”.

As I shepherded Lord Hain through my sheaf of printouts, I was struck by the depth of his knowledge and his quiet fury at the toll corruption was taking on the land of Mandela’s dreams. Now and again, a flat vowel or a sharp-edged consonant would accentuate the English peer’s down-to-earth origins, connecting him in heart and soul to his home from home.

I wasn’t expecting much to transpire from my informal meeting with Lord Hain at the Centre of Memory. I just wanted to cast some human light and shade into his body of understanding.

Then, a few weeks later, when he had settled back into his office at the Palace of Westminster, came what I would call “the Lord Hain letter”: the strongest public revelation yet of the David-vs-Goliath battle between a multinational financial institution and a small South African charity.

On the official House of Lords letterhead, with the English lion and the Scottish unicorn guarding the crowned shield of the British Isles, the Right Honourable Lord Hain of Neath addressed Ms Lynne Owens, CBE QPM MA, Director-General, National Crimes Agency. The topic? “Complicity in serious wrong-doing by HSBC Holdings and HSBC in South Africa against a vulnerable charity, Education Africa.”

The open letter was just over five pages long. “HSBC was a trustee of Education Africa,” writes Lord Hain, “its first representative on the board of this charity being Mr Krishna Patel, the then Group General Manager and CEO of HSBC Africa. Mr Patel and his colleagues were involved in a string of wrongdoings against Education Africa, including likely criminal wrongdoings, but this has not been addressed by HSBC Holdings Plc, no doubt to protect their colleagues.”

What follows is a methodical, blow-by-blow account of HSBC’s wrongdoings, as revealed in the forensic investigation. Among them, just to recap: fraudulent access to Education Africa’s bank account; unauthorised withdrawals from donor projects for unrelated purposes, amounting to theft; the deletion of profiles, correspondence and financial information from Education Africa’s computer system, in contravention of the Electronic Communications and Transactions Act; and the defamation campaign that accused me of financial mismanagement and the ill-treatment of children, which the forensic investigation found had no substance.

No public apology

“What makes matters worse,” observed Lord Hain, “is that HSBC Holdings has been given every opportunity to put things right, but has rather chosen not to compensate Education Africa fairly and did not make a public apology to enable the charity to get back on its feet. It took no steps to approach the donors as would have been appropriate to reassure them of the good management of the charity and its need for support to further a just cause.”

One might contend, as indeed HSBC did, that the “full and final settlement” of £2-million, payable in instalments over three years, had put paid to the matter once and for all, “without an admission of liability or wrongdoing on the part of either party”.

But not in Lord Hain’s view. “The charity was compelled to enter into a poor settlement by HSBC Holdings,” he notes. “The bank refused to compensate our unsung heroes who have dedicated themselves to the service of Education Africa and who have committed their lives to helping disadvantaged South Africans gain access to educational opportunities.”

Lord Hain goes on to draw a distinction between the “lives torn apart” at Education Africa — the loss of jobs, job security and financial wellbeing; the negative impact on health; the subsequent loss of one staff member’s home — and the absence of consequences for those involved in “the shenanigans of HSBC”, who had remained secure in their jobs, drawing big salaries, bonuses and pensions.

It’s unsurprising that the bank chose to maintain a stoic silence when Lord Hain’s letter was made public. It was as if a vault had slammed shut, allowing neither light nor air — nor money — to escape. DM

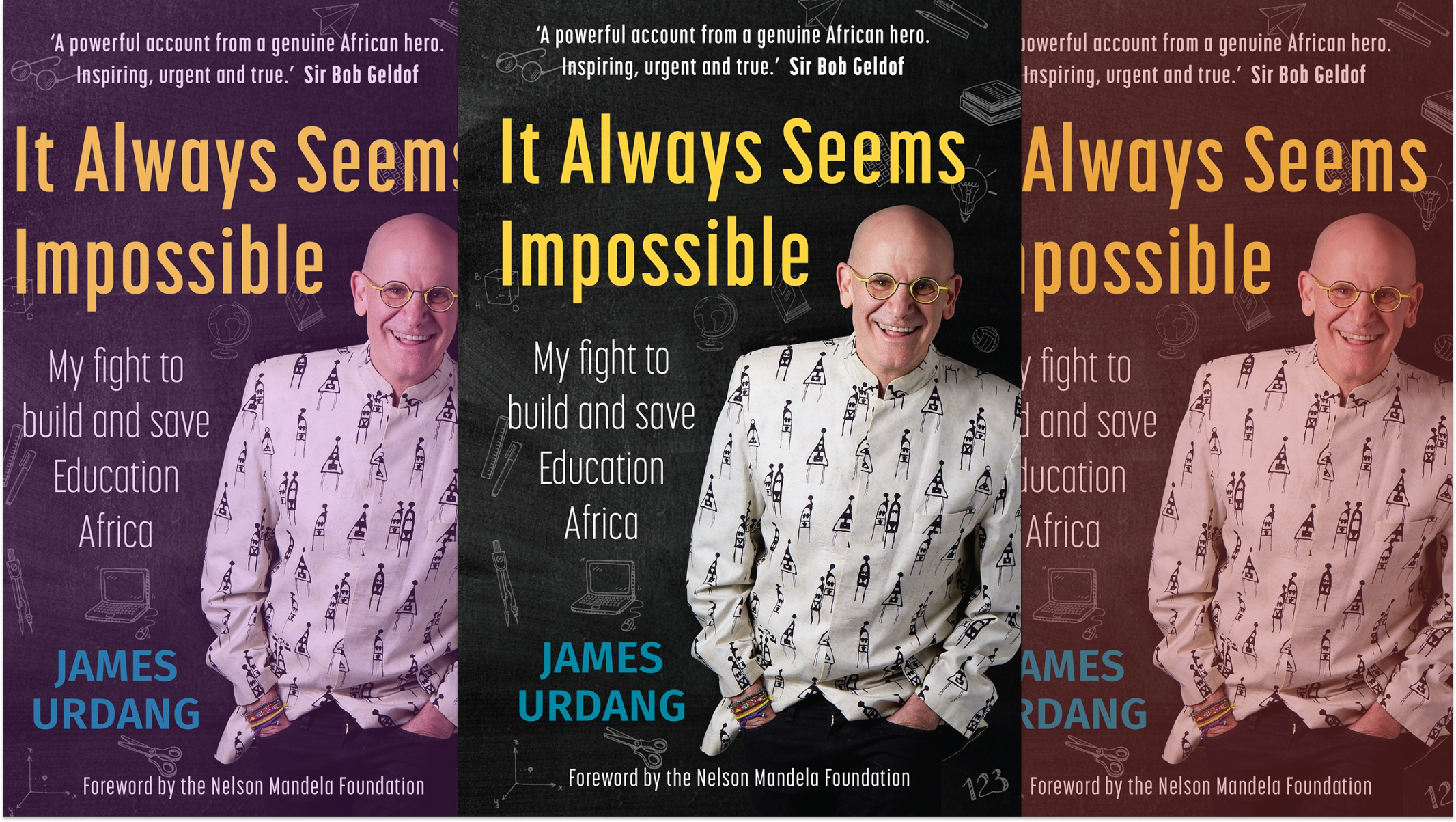

It Always Seems Impossible: My fight to build and save Education Africa by James Urdang is published by Bookstorm. Available in all good bookstores. Recommended Retail Price: R360