The South African Reserve Bank’s (Sarb’s) de facto target for consumer inflation is now 3%, and the Treasury has signalled it will set this — or something close to it — in policy stone sooner rather than later.

In theory, this should help anchor what economists call “inflation expectations” at lower levels and, in the long run, lead to slower inflation and lower interest rates.

To wit, the Treasury and the Sarb issued a joint statement earlier this week on the issue of the inflation target, which is still “officially” within the 3%-6% range.

This came in the wake of the July announcement at the conclusion of the last meeting of the Sarb’s rate-setting Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), which stated that it was now effectively aiming for the bottom end of that band, meaning 3%.

Read more: SARB signals focus is on bottom of inflation target range

“With the post-pandemic surge in inflation fading, National Treasury and the Sarb have analysed and discussed the value of reducing inflation to levels consistent with the country’s trading partners,” said the joint statement.

It went on to note that the MPC in July “expressed its preference for consumer price inflation to remain low, around the bottom end of the current target range of 3‒6%”.

A joint technical team from the Sarb and Treasury has been crunching the numbers on the subject of adjusting the inflation target, and the statement said the team’s work was now almost finished.

“The minister of finance and [Sarb] governor will agree on any changes to the target band. The minister of finance will make a formal announcement as soon as is practical to anchor expectations,” said the statement.

The bottom line is that — as is widely expected — Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana will probably soon make a pronouncement on the new inflation target, and 3% is the magic number.

“It’s an important message, and the very fact that we’ve had this clarification reinforces the Sarb’s choice of a lower inflation target. We will have to see what the formal recommendation is, 3% or a band with 3% at the mid-point. Either way, the market’s anticipation is that it will align around the 3% level,” said Razia Khan, chief Africa economist at Standard Chartered.

She said Godongwana’s pronouncement on the issue “couldn’t come soon enough, and this just consolidates the expectation of 3% being achieved on an ongoing basis, and it is certainly very welcome news”.

The Sarb, it must be said, has not plucked 3% out of the sky. Much research and modelling went into this, and Sarb Governor Lesetja Kganyago has been talking up the benefits of a lower target for some time.

The case of Chile

In a speech in October last year to the Department of Economics at Stellenbosch University, Kganyago made an instructive contrast with Chile to drive home the point that a lower inflation target means lower inflation.

Read more: Reserve Bank governor Kganyago brings clarity to the costs of getting SA inflation to 4.5%

“In 2000, both Chile and South Africa adopted inflation targets. Chile went for 3% and we went for a range of 3%−6%. Since then, our inflation has been higher than Chile’s by 1.8 percentage points, on average,” he said.

“This may not sound like much of a difference, but if you look at price levels, Chile’s prices are now 2.8 times what they were in 2000, while ours are 4.5 times higher. It was not that we faced a higher world oil price or a higher wheat price. The difference was that we had a higher inflation target.”

Among other things, inflation targets anchor expectations around the targeted level. And if inflation stays lower for longer, then interest rates come down and stay lower for longer.

At the conclusion of the May MPC meeting — two months before the Sarb announced that it was for all intents and purposes targeting 3% — the statement referred to research on the subject.

“For a 3% objective, our quarterly projection model shows a lower path for interest rates. Both our baseline and the 3% scenario have a cut in this quarter. However, rates move steadily lower in the scenario as inflation comes down,” said the May MPC statement.

“The policy rate falls to just under 6%, rather than staying above 7%. Inflation expectations stabilise at 3% during 2026, helped by the experience of lower inflation.”

For anyone paying attention, the Sarb was strongly hinting that it was moving to a 3% target.

“The Sarb has been very clear on this ... under a 3% target inflation targeting scenario, the repo rate declines to even lower levels than otherwise would have been the case. And the governor has said, ‘Come on, this is conceptually correct.’ If you have lower inflation, you have lower interest rates over time,” said Khan.

This, in turn, lowers the cost of borrowing, boosting economic activity and growth, while protecting savings and incomes from the evaporation that comes with high inflation.

Among other things, it will be of more than passing interest to see how this all plays out in wage negotiations across various sectors. In mining, for example, many of the wage deals inked in recent years have been linked to inflation. Will workers now settle for 3% or 4% when they have been getting 6% or more?

South Africa’s consumer price index (CPI) is at 3.5% and the Sarb’s key repo or lending rate is 7.0%, while the prime lending rate for consumers is 10.5%.

Few economists see another rate cut this year. But if the CPI can get locked in an orbit of around 3%, then the stars will line up for lower interest rates down the road. The Sarb is aiming high by bringing the inflation target low. DM

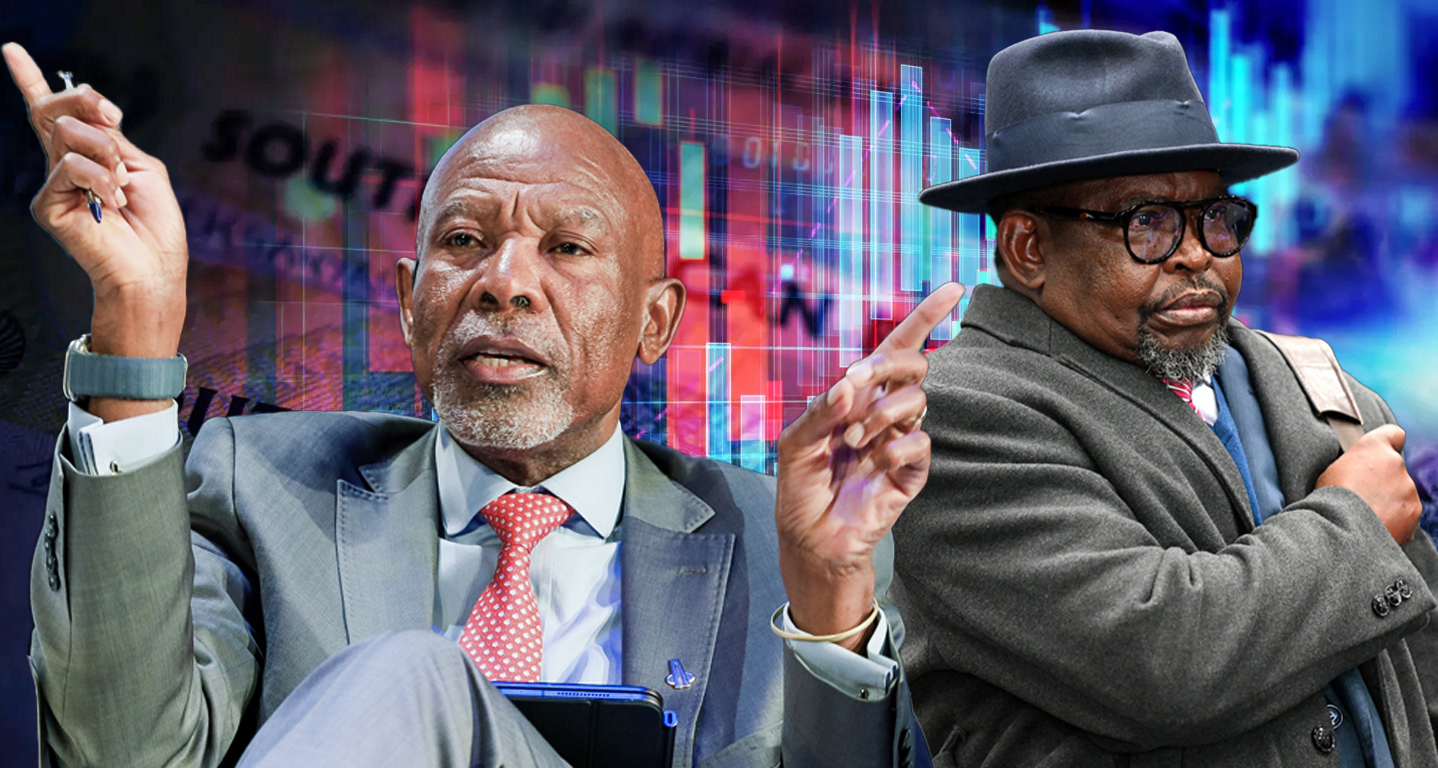

Illustrative image | Inflation rate graph. (Photo: Waldo Swiegers / Bloomberg via Getty Images) | South African banknotes. (Photo: iStock) | Sarb Governor Lesetja Kganyago. (Photo: Fani Mahuntsi / Gallo Images) | Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana. (Photo: Phando Jikelo / RSA Parliament)

Illustrative image | Inflation rate graph. (Photo: Waldo Swiegers / Bloomberg via Getty Images) | South African banknotes. (Photo: iStock) | Sarb Governor Lesetja Kganyago. (Photo: Fani Mahuntsi / Gallo Images) | Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana. (Photo: Phando Jikelo / RSA Parliament)