South Africa’s beloved comedian, Celeste Ntuli, has built a career on making people laugh. But when she speaks about her lifelong struggle with obesity, the humour carries an edge of truth. Experts warn that the condition is a chronic disease driving hypertension, type 2 diabetes and more than 230 health complications.

The 46-year-old comedian and actress, who grew up in rural Empangeni, KwaZulu-Natal, recalls being the only overweight child in her family.

Ntuli grew up in a family of four sisters, but was the only one who carried extra weight.

“All my sisters are slim — I was the odd one out,” she said. “At home, it was always, ‘What happened to you?’ as if I’d done something wrong.” She believes her body type comes from her aunts, rather than her parents. “I inherited their curves and size — it’s in my DNA. I didn’t choose this body; I was born into it.”

However, in her community, size was never stigmatised.

“Being big was not just acceptable — it was celebrated. I watched my aunts, and older women, proudly carry their size. From them, I learnt that shame can be attached to your body, yes — but I also learnt to carry it with dignity,” she said.

But things changed when she went to school in Durban. Her quick wit became both shield and weapon.

“Humour became my armour. I learnt to crack a joke before anyone else could, or expose their weakness, to disarm any body shaming at school.”

As Ntuli’s career grew, public scrutiny of her body sharpened.

“On stage, my size was part of the punchline — sometimes mine, sometimes theirs. Off stage, it became a conversation about health, beauty and worth. And those are not easy conversations in a world obsessed with body image.”

She highlighted the cultural nuance that still frames weight in South Africa.

“In African families, losing weight invites suspicion. ‘Are you okay? Are you sick?’ they’ll ask. Gain weight? ‘Oh, you’re happy and being taken care of.’ That’s the framework many of us grew up with.”

Now prediabetic, Ntuli has shifted her focus. “We must separate health from this narrow definition of beauty,” she said. Food, for her, has always carried deep meaning. “Food for me is love — it’s family, it’s comfort, it’s culture.”

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/ED_393248.jpg)

Her tastes remain rooted in tradition. She laughed as she described inyama yenhloko — the whole cow’s head — as one of the best meals, “with no translation in English”. This dish, a staple in many South African cultures, is often prepared for special occasions and celebrations. Friends and family, she added, know her for a good curry. At the same time, her most nostalgic food memory is a bowl of maas, the fermented milk she affectionately calls “rural couscous”, a staple from her childhood.

She insisted: “I love food — who doesn’t? But loving food shouldn’t mean I hate my body. The two can coexist — enjoyment and health — but it takes knowledge, access to resources and, at times, medical intervention.”

In a battle to lose weight, Ntuli admitted to trying everything from intermittent fasting to boot camps, gym and even attempting a gruelling 15km run.

“I died after an hour at that boot camp,” she joked.

Her search for quick fixes once took a bizarre turn.

“I once drank urine because someone said it would help me lose weight,” she recalled, pulling a face. “It was the most horrible thing I’ve ever done — I’ll never do that again.”

Despite the missteps, she remains pragmatic.

“I try to stay disciplined, but sometimes my working schedule, previous injuries, or just life get in the way. I’ve learnt to give myself grace.”

Ntuli spoke to Daily Maverick on the sidelines of the Novo Nordisk Wegovy media launch last week in Rosebank.

A public health emergency

Ntuli’s story is far from unique. South Africa has one of the highest obesity rates in sub-Saharan Africa: two in three women (68%) and nearly one in three men (31%) are overweight or obese, according to Statistics South Africa (StatsSA). The consequences go beyond aesthetics — obesity is a chronic disease recognised by the World Health Organization (WHO) linked to more than 230 health conditions, from type 2 diabetes to cardiovascular disease and certain types of cancer.

The International Diabetes Federation estimates that 2.4 million adults in South Africa live with type 2 diabetes, with most cases directly linked to excess body fat. The financial cost is staggering: overweight and obesity cost the public health system R33-billion annually, about 15% of the government health expenditure, a figure that should raise concerns about the economic impact of this public health crisis.

Dr Kershlin Naidu, a Midrand-based specialist endocrinologist with decades of experience treating type 2 diabetes and obesity, has sounded the alarm: “We are dealing with a public health crisis hiding in plain sight.” Naidu added: “Obesity is not simply a matter of willpower or lifestyle choice — it is a chronic, relapsing condition.”

Sara Norcross, general manager of Novo Nordisk South Africa, added: “Obesity is not a choice — no one wakes up and decides to be obese. It is a chronic disease, and we must stop reducing it to myths and moral failings.”

Moving beyond blame

Experts stress that focusing on “eat less, move more” oversimplifies the issue. Professor Arya M Sharma, Emeritus Professor of Medicine at the University of Alberta, told the Cardio-Kidney-Metabolic (CKM) Africa Summit 2025 in Cape Town: “Some people are naturally slender, but most sit on a spectrum where genetics and biology dictate weight gain, even with identical diets and activity levels.”

He explained that the brain’s powerful homeostatic system was designed to defend body weight against loss.

“The minute you stop dieting, your weight fights to return,” he said. Another brain system, the hedonic or reward system, drives eating for pleasure rather than hunger, making sustained weight loss a complex battle against deeply rooted biology.

Living with the weight of stigma

For Ntuli, stigma often bites deeper than the medical realities.

“Your body tells your story, but it’s not the whole book. We deserve to write chapters about joy, movement, breathing easily when we walk upstairs — not just how we look in photos.”

Her honesty struck a chord during the Rosebank obesity awareness event, at which she spoke of the guilt, excuses and exhaustion that often come with fluctuating weight. She admitted she sometimes avoids exercise, not out of laziness, but because of injury fears, long workdays, or sheer fatigue.

“I genuinely feel like my life is one long treadmill — up at five, home after midnight. So sometimes I just can’t.”

Yet she carries her size with humour and defiance. She quipped about body shaming: “I’ve got comebacks for days. If someone comments on my weight at a family gathering, I remind them of their faults (like not finishing matric) — and they keep quiet.”

Ntuli reflected on how weight filters into her personal life, particularly dating.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/ED_182518.jpeg)

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/ED_498476.jpg)

“I’ve dated guys who actually prefer big women,” she said, laughing. “But society doesn’t always allow you to believe that love and attraction can exist outside narrow beauty standards. I’ve had to learn to carry myself confidently — because if I don’t, people assume size means insecurity.”

Yet, as she put it, “I am single and I don’t have children.” She explained herself in unprovoked honesty: “I am a leaver,” she said, explaining that if something doesn’t feel right in relationships or life, she chooses to walk away rather than remain unhappy.

While the pharmaceutical company hosted the Rosebank event, Ntuli’s presence underscored a broader message: obesity is not only about new medications, but about lived experiences, culture, stigma and survival.

Ntuli’s voice — mixing mischief, vulnerability, and insight — places human stories at the centre of a national crisis too often reduced to statistics or industry product launches.

Minister of Health, Dr Aaron Motsoaledi, told Daily Maverick: “Endocrine disorders, including diabetes mellitus (type 2 diabetes), have been prioritised for review in the current phase of the Standard Treatment Guidelines and Essential Medicines List. All identified medicines — including glucagon-like peptide-1 agents such as semaglutide (Wegovy®) — will undergo rigorous health technology assessments as part of a comprehensive package for diabetes, obesity and cardiovascular disease management in South Africa.” DM

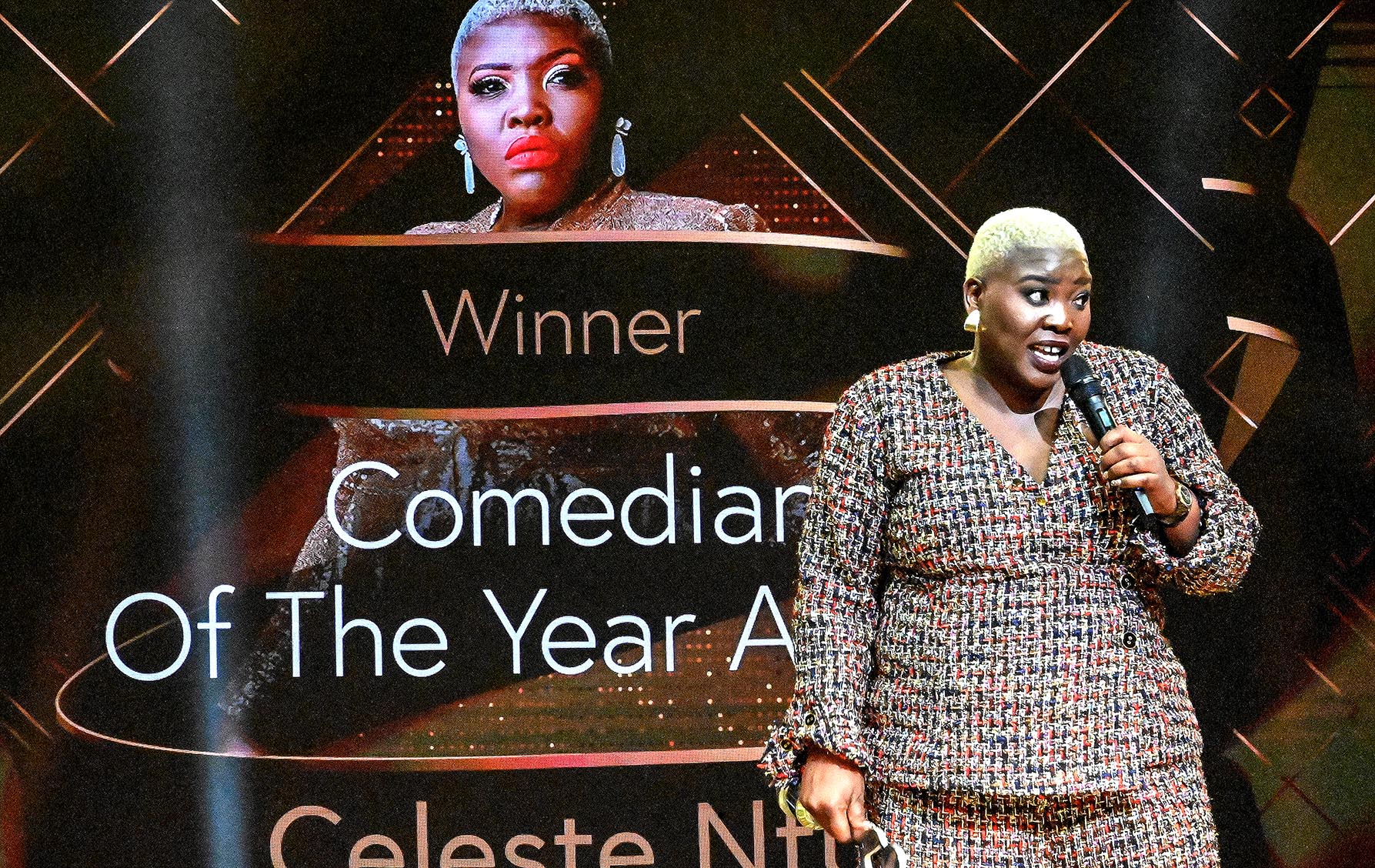

Celeste Ntuli during the Savanna Comics Choice Comedy Awards at Gold Reef City on 12 April 2025 in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Oupa Bopape)

Celeste Ntuli during the Savanna Comics Choice Comedy Awards at Gold Reef City on 12 April 2025 in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Oupa Bopape)