In the morning, I woke to an excruciating burning between my thighs. I tried to stretch, but it was too painful. From outside came the sound of sheep bleating in the distance, the high-pitched whistles of shepherds. I tucked my legs close to my body and wrapped my arms around them. My head pulsed. I felt utterly alone.

I didn’t want to leave the safe darkness of our hut. Something told me I needed to hide from the tall man and his comrades. That he was coming back for me, that it wasn’t over yet.

Footsteps – someone was walking towards the hut.

I panicked. Where was YaZiana?

“Good morning, popi.”

Instant relief at my sister’s voice.

Behind her, through the door opening, I could see Lola and her mother. Mama Nzembo was wearing a green dress with a black shawl wrapped tightly around her face.

“Good morning, Ziana. Oza ndenge nini?” Mama Nzembo asked softly as she entered our hut. “I have come to check up on you girls. How are you doing, Popina?”

My mouth couldn’t form any words. I felt sick.

Nyota, one of the village girls, called from outside. “Popina! Lola! Come play!” Nyota was funny – her hair was short like a boy’s, and she wore only boys’ pants because she had eight brothers and her mother said there wasn’t money for girls’ clothes.

We didn’t feel like playing, not this morning, but YaZiana insisted that we join the game – she needed to start her daily chores. Mama Nzembo offered to watch us.

I got up from my bed on the floor and stood in the doorway. I could see the girls playing ukugenda outside. Over the road from our hut, the boys were playing soccer. I watched as someone kicked their ball into the forest and a boy called Beya ran to fetch it. He was coming out of the bushes when a bullet pierced his head.

I was just standing there in front of our hut.

And I saw Beya die.

And then gunshots shook our hut and suddenly there were soldiers everywhere. YaZiana, Mama Nzembo, Lola and I, standing there together as soldiers came out of nowhere, running in all directions, stopping and searching people – what for? – firing guns, torching huts.

Everything happened in slow motion. I felt as if I had left my body and was looking at the scene from somewhere else. All around us huts were going up in flames, mothers screaming for their children. I saw a man kneeling, his hands raised in the air. A single bullet in the back.

Soon the ground was littered with bodies, limp and lifeless like cloth dolls, but these were people I knew.

I looked around me, rooted to the spot. Was this really happening? My mind told me to run, but my limbs wouldn’t move. My child-brain didn’t comprehend this. Couldn’t comprehend that Burundian rebels were invading our village. Collecting people. Collecting little girls and boys. Killing the older men and women.

All around me, people were dying. I gazed out over the wasteland that had been our village, our home.

And then a shot rang out, much closer.

Mama Nzembo collapsed. Blood poured out of her mouth as she hit the ground. Lola screamed, then was off like lightning to reach her. She put her hands around her mother’s neck.

A sound raw with grief. “Wake up! Wake up, Mama! Please!”

A boy in a soldier’s uniform tried to grab Lola and pull her away, but she tightened her grip. He struck her, bright-red streams flowed down her face. She kept clinging to her mother but the boy, impatient, tore her away.

My sister was holding me. Now she grabbed Lola. The village was so open – we could run into the forest. But the soldiers were shouting commands to those who were still alive. Anyone who dared to run was shot. I didn’t understand their language, but YaZiana did: we had to line up in two rows, females and males separately.

A white truck idled past our line, spitting a suffocating cloud of dust in our faces. Stern-faced young men and boys sat on their haunches in the back, guns slung casually over their shoulders. Some already had beards, some had bushy hair and some wore red turbans. A young man with thick knitted eyebrows swatted the side of the truck with a whip. When my eyes met his, it felt like my flesh had shrunk against my bones. He looked away and I started breathing again.

“What’s the matter with you?” YaZiana hissed. “Don’t stare at them! Keep your eyes on your feet when the soldiers are near you. Do you understand me?”

They handcuffed us and put shackles around our ankles, linking us with chains and padlocks. With wide eyes I glanced over at YaZiana. Lola was crying.

They commanded us to start walking but the weight of metal made it hard to move.

“We’re going to be alright, don’t worry,” YaZiana tried to reassure from behind me. “Be very quiet. Don’t look anyone in the eyes, Popina. Always keep your head down. Same for you, Lola.”

I glanced back at the village. I could feel the heat of the flames on my face – our home being consumed by fire.

The dark-grey smoke shrouded the morning sun.

The world was in flames.

***

So many bodies falling down.

And I am so small.

What are they going to do to us? Will I end up dead too?

This is the end for me.

***

My feet hurt. I was exhausted and hungry. Terrified.

In the afternoon, after walking, chained, for hours along a narrow footpath, we reached the village of Kumase.

I had never been to Kumase, but the people of my village often travelled there by donkey or horse to trade livestock, seed and crops. The village was known to be very beautiful, a jewel in the crown of the DRC. Its lush rolling hills were shrouded in soft mist and people said it was impossible not to see the hand of the Creator in the green valley and sparkling lakes. They said that the hearts of the Kumase people reflected this beauty – they were known for their kindness and loving nature. Some said the people from Kumase, the Muswahilis, were taller than us, with light skins and narrow noses – our people, the Bangalas, were shorter, darker and broad-nosed. But the two tribes had been marrying each other for centuries. We shared the same history, we had the same culture and we farmed the same land.

To my childish eyes, we were one people.

As we entered the village, the rebels wasted no time – they did what they had done in our village. There was a cacophony of gunshots and shouting, and fires started lighting up everywhere. Soon children’s bodies were scattered all over the ground, people screaming while being chained. Were my eyes deceiving me? Was this how people treated other people?

The rebels made us prisoners kneel on the ground and pointed guns at us. No one dared move. I was leaning forward, my head facing down, when I heard a woman cry out close to me. Looking across at her, I could see that she was pregnant. Tears were streaming down her face, and her dress was covered in blood.

“My baby! My baby! My baby!” she was screaming. “Please help me!”

One of the soldiers walked over to her. He raised his gun to her swollen belly. Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang! She fell, and for a moment, her chest kept rising and falling. But then it stopped. Her eyes turned glassy, her arms limp. Four shots, two lives.

Behind the woman was a beautiful teak tree. A young man was tied to the tree trunk with a rope, his face puffy and turning a pale shade of blue, his clothes shredded and bloody.

Next to me, Lola was trembling uncontrollably.

“It’s your own people you are killing,” a voice said from the line of men next to me. It belonged to an old man, his right cheek bleeding. He barked a wet cough and spat on the ground. Then he looked straight at me. “Keep your eyes on your feet, little girl,” he said more quietly.

I started crying. I am going to die. I am going to die. I am going to die.

But then a voice whispered in my ear: Not today, Popina.

I am going to die – the only thought I had.

You are not, the voice whispered.

I looked around. “YaZiana,” I whispered, “can you hear that voice?”

“What voice?”

***

The rebels captured many more people in Kumase, chaining them up like animals. Finally, we moved on, about eighty captives of men, women and children, leaving behind only smoke, ashes and death. Taking only memories of the lives we used to know. DM

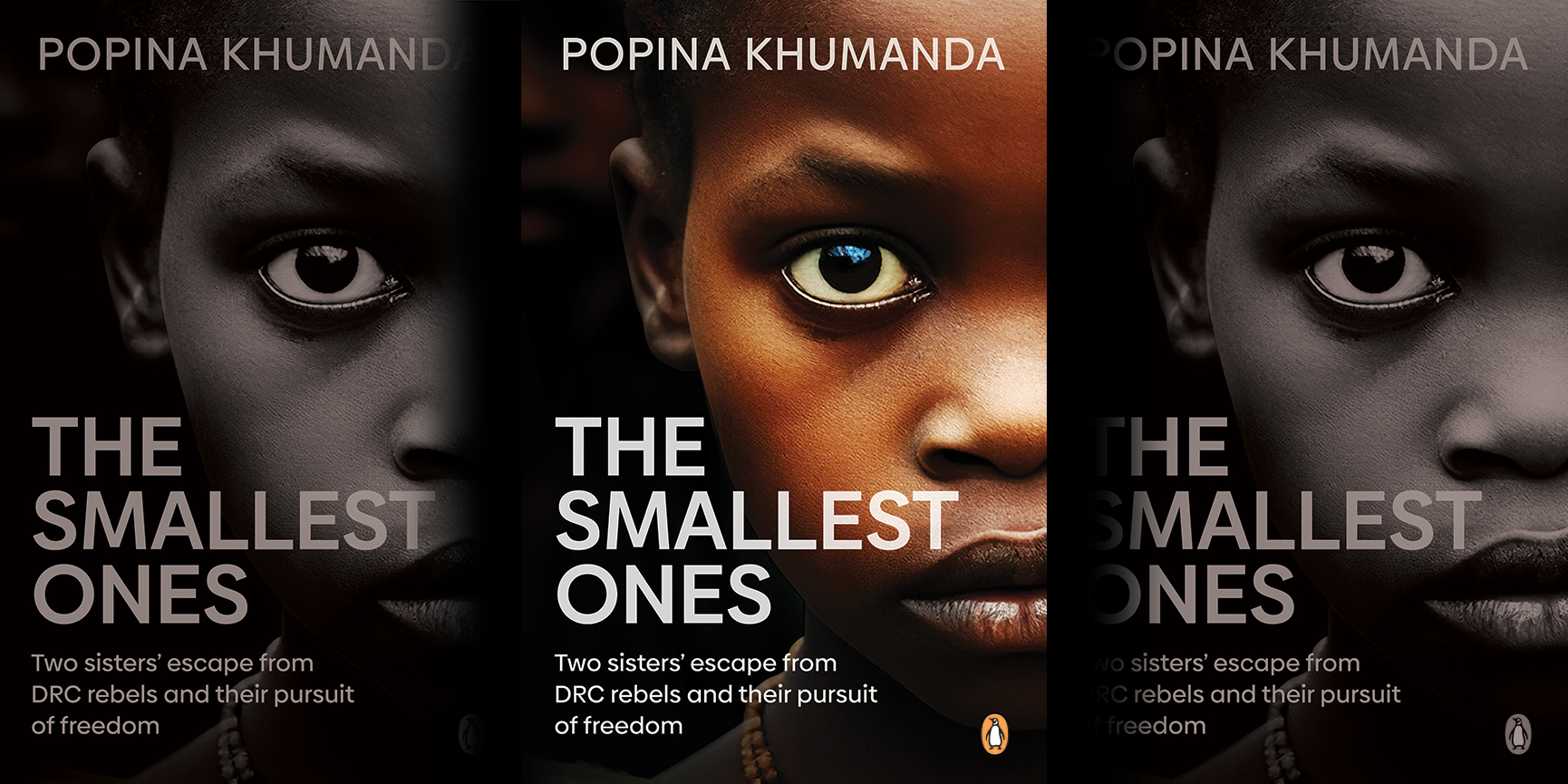

Image: Supplied

Image: Supplied