On Friday, President Cyril Ramaphosa said the DA’s refusal to join the National Dialogue was the “worst form of hypocrisy”. Others in the ANC have said that if DA leader John Steenhuisen refused to join the interministerial committee driving the process, it would be an act of defiance against the President.

This shows that while the DA’s announcement that it would not join the dialogue was initially viewed as a weak response to the sacking of the DA’s deputy minister Andrew Whitfield, it has hit home with Ramaphosa and the ANC.

It is more proof that, after the coalition has been in office for more than a year, personal relationships between the leaders of its two main parties have not improved.

Both the ANC and the DA can point to incidents for which they can blame the other.

The DA could say it started when Ramaphosa signed controversial Acts, including the Basic Education Laws Amendment Act and the Expropriation Act, into law. They can claim this was deliberately provocative, designed to weaken them.

The ANC can argue that the DA’s ministers have defied or contradicted policies adopted by previous governments, such as Minister of Communications and Digital Technologies Solly Malatsi’s decision to withdraw the SABC Bill.

While the ANC can argue that the DA should never have said it would vote against the Budget, the DA can respond that the ANC should have consulted with it on the two percentage point VAT increase beforehand.

Within this are incidents that appear to be deliberately disrespectful.

Basic Education Minister Siviwe Gwarube would have been expected to attend the signing ceremony of the Bela Bill. However, politically, this was impossible as she had promised her DA constituency that she would oppose the Bill.

ANC supporters might well feel she was wrong not to attend the ceremony; DA supporters will believe Ramaphosa deliberately put her in this awkward position.

To go any further down the rabbit hole of who is to blame for what will solve nothing.

Lack of trust

What is clear is that there is a complete lack of trust between the two parties — and, without trust, it may be impossible for them to agree on anything.

The importance of a personal relationship can be underestimated in difficult political times.

An authoritative account of South Africa’s negotiations towards democracy during the 1990s focused on an incident that helped engender trust between the ANC’s chief negotiator, Ramaphosa, and the apartheid government’s negotiator, Roelf Meyer: when a fishhook got caught in Meyer’s hand, he asked Ramaphosa to remove it.

At the time, all of those involved in the negotiations had a huge incentive to engender trust.

All sides claimed to want a democratic solution and to avoid violence.

Also, most of those involved knew very little about each other. When the process started, many of them had never met.

Even then, there were angry words between Nelson Mandela and FW de Klerk, and moments of great tension.

The situation now is very different.

It is not just that the politicians know one another; it’s that they all have long histories of shouting and screaming at each other.

The ANC was in power for so long by itself, and the DA in opposition for so many years, that it is easy for members of both parties to fall back on what they know.

It can almost seem as if their leaders are most comfortable when fighting each other.

Another factor is that there was virtually no preparation for the leaders before they had to work together.

Before the election, when the DA was trying to form the Moonshot Pact — a group of parties that could, together, beat the ANC — leaders understood how much work had to be done beforehand.

Workshops

The founder of the Democracy Works Foundation, Professor William Gumede, ended up running workshops between the leaders of the parties involved in that pact, trying to engender trust between them.

There was none of that in this national coalition government.

Another factor is the sheer social distance between the leaders of the parties in the coalition.

They have grown up in such different circumstances that it may be difficult for them to understand each other.

This might seem strange when there is plenty of evidence that millions of South Africans from very different communities interact productively every hour of every day.

But in our politics, the more a leader can attack other groups, the more they are rewarded.

While the ANC and the DA are in SA’s political centre, their leaders have very strong views on issues, which makes it harder for them to work together.

And it should not be forgotten just how tough our society is, how raw the disputes are.

When the PAC recently brokered a meeting between the ANC and Afrikaner groups (in another indication of how interesting and complex our society is), it described the discussions as having “blood on the floor, blood on the wall”.

This is because of how far apart these groups are, and how their leaders have to manage difficult dynamics.

Of course, one hopes that our leaders can rise above all of this.

For the moment, it is a forlorn hope. DM

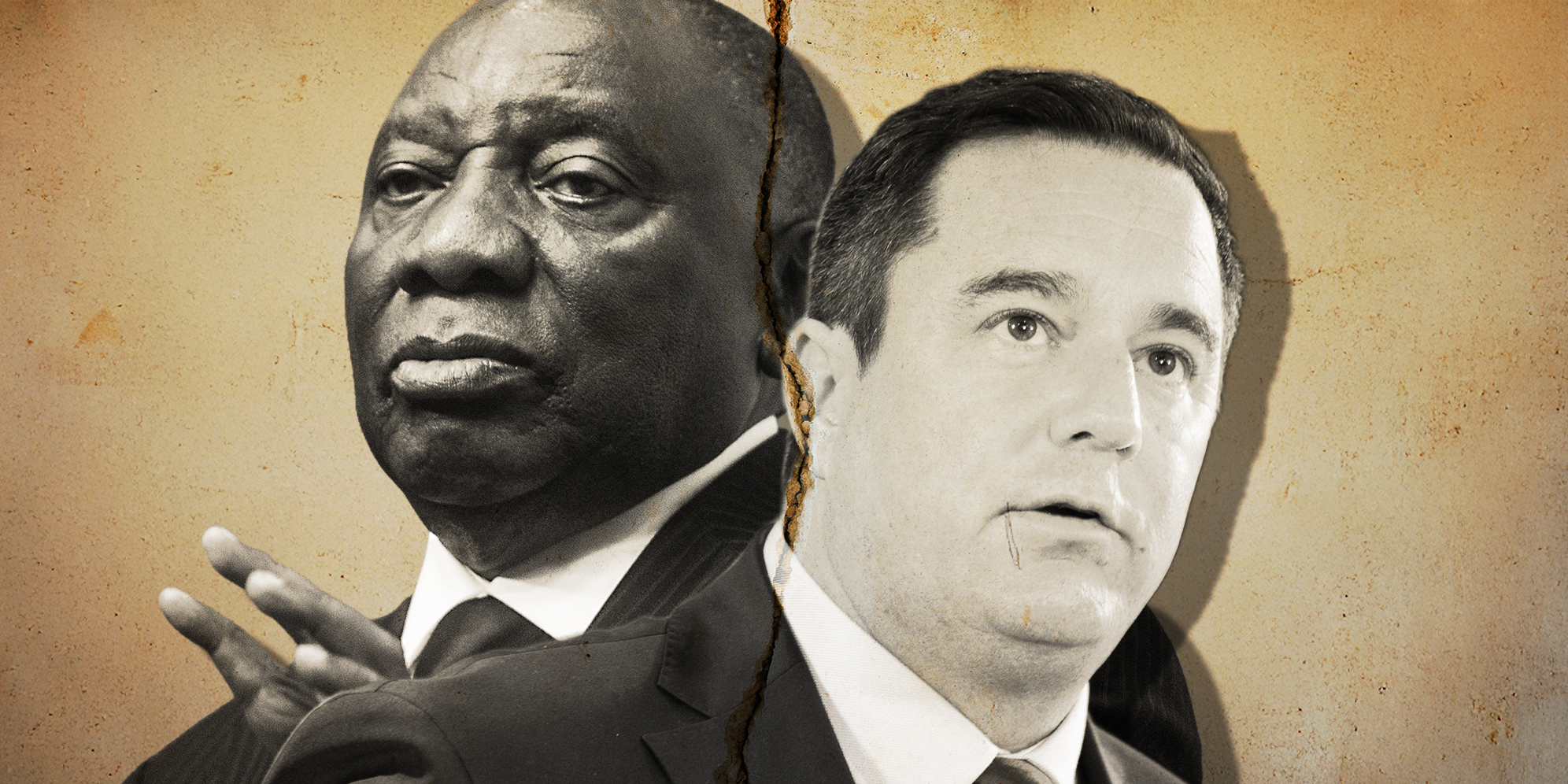

Illustrative Image: President Cyril Ramaphosa (Photo: Gallo Images / Brenton Geach) | DA leader John Steenhuisen. (Photo: Gallo Images / Misha Jordaan)

Illustrative Image: President Cyril Ramaphosa (Photo: Gallo Images / Brenton Geach) | DA leader John Steenhuisen. (Photo: Gallo Images / Misha Jordaan)