South African author Maren Bodenstein paints the picture of her upbringing living in the tiny village of Hermannsburg in Natal in her new novel, The Sinner's Bench. From extracts of letters and homespun publications to family myths and childhood memories, dark secrets are bound to make an appearance.

In this extract, the writer finds an article from 1982 that sparks old memories about her family's dark past.

***

In the kist, I found a photocopy of a photocopy of an article published in Scope (26 February 1982). The heading, The Ghost of Adolf Hitler, is written in a heavy Gothic font, popular with the Nazis. The article tells the dramatic story of the oil painting of Adolf Hitler, apparently signed and donated to Hermannsburg by the Führer himself, that hung on the wall of the dining hall – the same dining hall on whose wall was written the injunction – Nurture the German language, protect the German Word. Because through it the spirit of our forefathers lives on.

And how one night, one Hymie Surendorf removed the portrait in the middle of the night to prevent skirmishes between the pro- and anti-German factions in the area. Hymie explained to the journalist that he only retrieved it from the family attic in 1982. And that, even though he could have got good money for the thing, he decided to return it to where it belongs – the Hermannsburg school.

And where was it now? I had never heard anyone mention it.

My parents did tell the story of how Onkel Kistner got the boys to dig a big hole one night before the war and that the pupils had solemnly buried all Nazi paraphernalia.

I don’t know if my parents had buried anything that night.

Years later, my brother Joppie and his friend unsuccessfully dug around for the stash. I never asked my parents much about their allegiances. Maybe I felt overwhelmed by the thought that those who raised me and whom I loved for so long were somehow part of the people who provoked a war which killed more than fifty million people and who used their administrative, logistic and technical efficiency to murder more than six million people in the concentration camps.

I had wanted to believe that my family was different. I wanted to believe that they had had the sense to see through the terrible deceit. Surely, if my ancestors were clean, I too am a little cleaner?

Of course, it was common knowledge that Hertha was a Nazi. She, after all, in old age unashamedly drew a tiny swastika next to her name on the family tree she created. But she was not really related to me by blood. So that was fine.

Grandfather Heini believed in the superiority of the German race. But he was also a pragmatic businessman who quickly adapted his ideology after the war. Although he never did stop believing in the superiority of the white race.

Grandfather Wilhelm seemed quite clean. Maybe it was because he took on British citizenship before the war. He was also never interned. And as a man loyal to his God, Hitler’s grand rhetoric sat uncomfortably with him. On the other hand, at the opening of the church hall in Moorleigh, the Nazi flag was hoisted under his watch. And during the school holidays, the Bodensteins read and argued about Mein Kampf, and The Myth of the 20th Century, a tome espousing racial purity and anti-Semitism. But maybe some of them had argued against all this ideology?

Christel was always a bit secretive and evasive about things she didn’t want to talk about. If you asked her directly, she would turn her head away coolly, avert her gaze. None of your business, said her body. She never implicated herself in the history of the Nazis. When she spoke about friends and relatives in Germany who supported the Nazis, she pointed out that they were people of their times. Just like the deeply racist missionaries were also people of their time. But there was one photo album with photographs of her as a young teenager playing the recorder. She was wearing a uniform. There were also pictures of uniformed children marching through the streets with Nazi flags. Christel among them. “What is this?” I asked her.

“It was just a camp. A Nazi youth camp,” she told me. “We sang Nazi songs and marched through the streets of Lourenço Marques every morning. I was probably chosen for my blonde hair and blue eyes.”

“How was it?”

“It was nice to spend time in Mozambique.”

“And the camp?”

“You know me, I’ve never been one for camps or uniforms or group activities.” DM

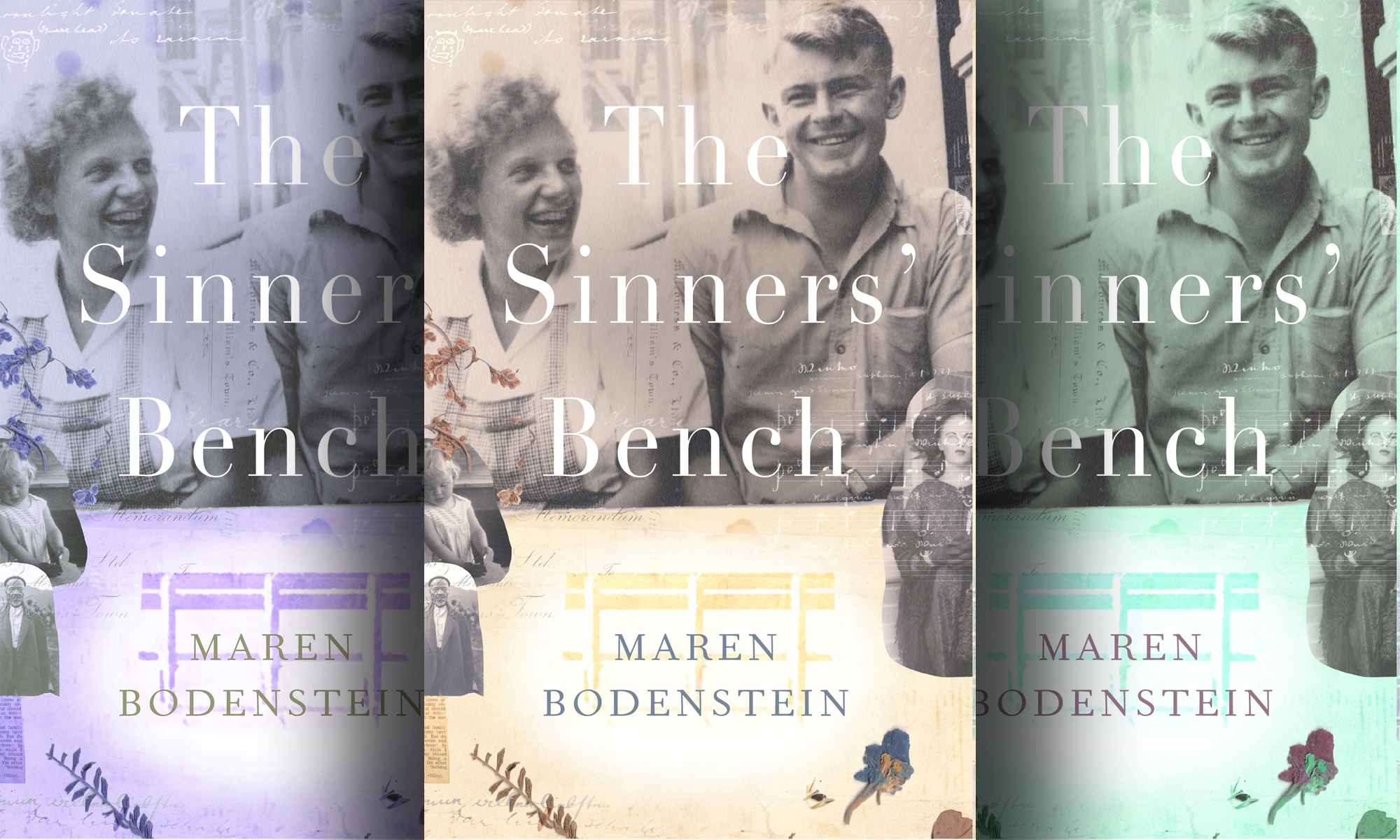

The Sinner’s Bench by Maren Bodenstein is published by Staging Post and is available at Exclusive Books. R300.

Book cover: Supplied. Image composite: Maverick Life.

Book cover: Supplied. Image composite: Maverick Life.