BUSINESS REFLECTION

After the Bell: Anglo’s possible demise was caused by half a century of poor choices

Wow, how the mighty have fallen. During the apartheid era, Anglo American controlled around 40% of stocks on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange by value. Fast forward 30 years and there is now a very good chance it will disappear entirely.

If BHP’s bid for Anglo announced this morning succeeds, and honestly I don’t see any reason why it or another like it won’t, it will constitute a very big mining deal in today’s landscape.

But in historic terms, it means something different. For one, it will represent the end of the Oppenheimer empire, although it should be noted that the remaining members of the Oppenheimer family themselves have already left the building. The family owns perhaps 2% of the company today. So it is arguable that to talk about Anglo as the “Oppenheimer empire” is a bit dated anyway.

But if you believe in corporate empires, where did Anglo go wrong?

Let’s start with the deal itself. BHP now towers over Anglo in scale, so although it might be an important potential acquisition for BHP, it’s by no means a game-changer. Anglo’s market cap is about $24-billion compared to BHP’s $255-billion, so depressingly Anglo is something of a snack for BHP — no more.

Is the bid fair? It’s probably a bit light, as you would expect going into a bidding process. As I write, if you take into account the jettisoning of Amplats and Kumba, the deal values Anglo at about 2,400 pence a share, Anglo’s shares are trading about 4% above the implied potential bid price. That can only mean two things: shareholders think that BHP will up its bid and/or that either Rio Tinto or Glencore will make a competing bid. You can bet a bunch of corporate finance teams are frantically hauling out their rulers right around now.

But let’s look back a bit because I think this is instructive. In discussion with colleagues and friends, we came up with five crossroads events in Anglo’s recent history where the company took the wrong turn which has led to its possible demise. You could call them places where the company “went wrong”, but in some ways that might be too harsh; there were reasons the company made the decisions it did at the time and it might have turned out very differently.

Ernest Oppenheimer, a Jewish German émigré, founded Anglo American 1917 in Johannesburg with the backing of American bank JP Morgan and a collection of UK banks; the name of the company reflected that debt. In a way, in that decision to capitalise itself, the company betrayed its core strategy; aggressive growth. The company’s history from then on for the next 50 years reflected its facility at both corporate acquisition and building mines from the ground up. Three pivotal moments were consolidating the diamond industry, discovering and exploiting the Free State gold fields, and essentially creating the Zambian copper fields. Underpinned by massively exploited local labour and boosted by huge ambition, Anglo’s first half-century was a powerhouse.

Politics

And then the company ran smack dab into politics. First in Zambia, where Anglo’s copper mines were nationalised, and then in SA, where the apartheid regime complicated the company’s ability to expand outside the country. By the time Harry Oppenheimer took over in late 1950, these effects were beginning to show. Unable to expand at pace outside SA, Anglo began its diversification inside SA, becoming a domestic mining/industrial complex.

Outside of SA, Anglo used the little it was paid for its Zambian copper interests to start Minorco, but here was perhaps one of the company’s missteps. Minorco was not unsuccessful but it certainly didn’t become a great stand-alone mining company. It was eventually unceremoniously absorbed into Anglo when the parent company listed in London. Perhaps it’s an unfair comparison, but just contrast what the Rembrandt group did with its, at first, tiny international interest; Richemont. The difference is stark. Minorco was treated as an afterthought and performed likewise.

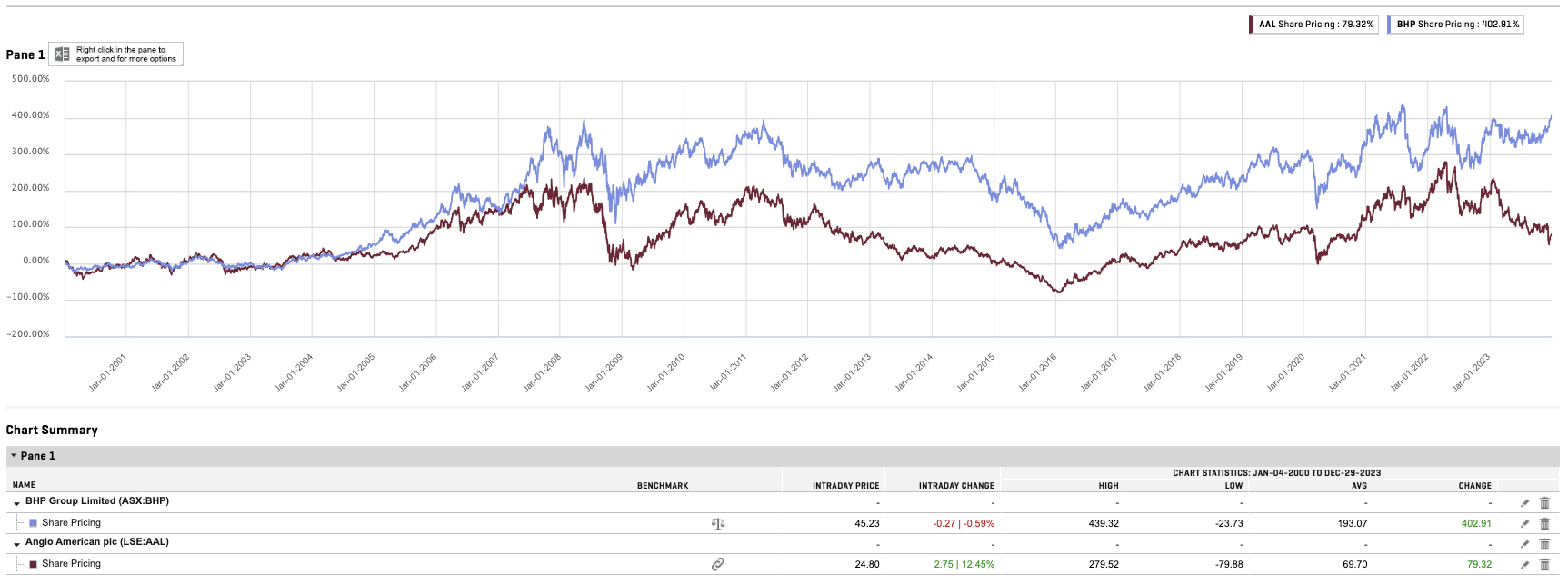

The second wrong turn was the decision to list in London, as I have written often before. But you know, if I had been at that pivotal meeting in the Brenthurst library just as the century was turning, I bet I would have voted in favour too. Funny old thing, life. The theory was that Anglo would join the biggest mining companies in the world there, BHP and Rio Tinto, cementing the London Stock Exchange as the global centre of mining. The cost of capital would be lower, Anglo would at last be free of all the constrictions of its birthplace, and it would be able to spread its wings to achieve its full potential. At the time, incredibly, Anglo was only a little smaller than BHP, despite its recent merger with Billiton, so expectations were high.

But instead, the London market did the opposite. For the first decade, London investors looked at Anglo with distrust and suspicion, found its complex structure with cross-holdings into De Beers and Anglo-Gold unwieldy, and its industrial interests weak and uninteresting. Anglo spent an enormous amount of time and effort creating an entity that was investable from the point of view of retirees from Shrewsbury. The idea of Anglo being a growth company was off the agenda while all that got sorted out.

It wasn’t as though Anglo didn’t try. The company made bids in exactly the right area: big Australian iron ore companies. But as a newcomer to the London market, Anglo was anxious to not overpay and thereby irritate London’s old-fashioned pin-stripe brigade even more than it was already. But the irony is that if Anglo’s bids for the Australian iron ore companies had succeeded, history would be very different because even at the highest bid price, they would have paid off in just a few years. Instead, the upside went to Anglo’s Australian competitors, BHP and Rio, who have made an absolute fortune from assets they were more or less forced to buy because of Anglo’s bids. So this too goes down as a fork in the rutty road that ended badly.

The next fork in that road, another fork missed rather than taken, was the emergence of China, which industrialised at a speed never seen before in history. Anglo, fooling around with its portfolio of odd interests, just kinda missed the boat. And that boat was boarded with vigour by BHP and Rio. In order to achieve its aims, China needed iron ore, and Australia had plenty. The geographical proximity, I’m sure, played into it, and the fact that the Chinese were always big customers.

So, having missed the commodity boom boat in the early 2000s, Anglo redoubled its efforts to catch up and ended up taking yet another wrong turn in the late 2000s. The company took a huge bet on Brazilian iron ore, buying the Minas Rio prospect in 2007 but building the mine, paying off title deeds holders for 500km between the mine and the sea, and just the enormity of the project, were frankly disastrous. As it happens, Anglo’s competitors made much bigger mistakes, but they were earning so much at this stage from iron ore, it just didn’t matter as much.

At last, Anglo chose a fork in the road that did pay off: it bought several South American copper mines that have turned out to be spectacular winners. More on this in a bit.

And finally, I have a potentially contentious suggestion about a road not taken: the fact that the Oppenheimer family lost interest in the company. I’m sure they had excellent reasons, and god knows, when you are that rich, ultimately what is the point in the exhausting, grinding job of running a global mining company? Nicky Oppenheimer bought De Beers from Anglo and then sold it back to Anglo, in two spectacular deals, absolutely securing the family’s financial legacy. But in the process, I think the company lost its soul.

Is that really important in this day and age? In some ways, we live in the era of professional managers, not corporate empires. Yet, particularly in the huge corporations of our day, having some relatable character and expertise with deep vested interests in the company can be a huge advantage. Just think of the value of Tesla compared to other car companies around the world, and what it might be worth if Elon Musk weren’t there.

Anyway, back to the copper interests. In its stumbling around, Anglo’s copper mines have hit a niche: copper will be crucial to a whole bunch of modern endeavours, including a host of new industrial efforts like electric cars and products to alleviate climate change. BHP have pretty much made it clear that this is essentially why they are making a bid for the company. BHP, which earns the vast majority of its profits from iron ore, is not even interested in Anglo’s iron ore businesses, or for that matter, its South African businesses as a whole; Kumba and Amplats will be unbundled and De Beers sold. What’s left? Copper.

So is Ernest Oppenheimer rolling in his grave at the thought of his empire possibly reaching its expiry date? I don’t know. But if he is, he is rolling very comfortably. And Anglo might still survive this intact.

But I think Anglo has been trying so hard in the recent past not to be South African, it’s come to be defined by what it isn’t rather than what it is, and there is a sad lesson in that. DM

Great read Tim. No doubt a few other choices along the way that never saw the light of day.