Bassirou Diomaye Faye’s election as Senegal’s youngest president on 24 March was celebrated domestically and internationally as confirmation of the country’s strong democratic tradition.

Observers believe that Senegalese citizens, and the youth in particular, the Constitutional Council and religious and political actors were impressively resilient in navigating an often violent three-year political crisis. They successfully resisted attempts to extend former president Macky Sall’s term in office.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Breaking of Senegal election deadlock a critical move in preventing further unrest and bloodshed

But alongside the praise is uncertainty about how Faye and his political mentor Ousmane Sonko, who has been appointed prime minister, might conduct Senegal’s external relations. Sonko, a firebrand critic of Sall who was disqualified from elections following his imprisonment for “corrupting the youth”, endorsed Faye’s candidacy for president.

The brief campaign period prevented candidates from presenting detailed manifestos. Nevertheless, questions about a possible repositioning of Senegal are borne out by Faye and Sonko’s pre-election rhetoric. Their party — Patriotes africains du Sénégal pour le travail, l’éthique et la fraternité – and its political allies issued a campaign programme that called for reclaiming Senegal’s sovereignty. It suggested reforming the CFA franc, introducing a new national currency, ensuring mutually beneficial international partnerships, and renegotiating unbalanced natural resources contracts.

Senegalese foreign policy has traditionally featured relations with four main strategic partners: France, Saudi Arabia, the United States (US), and Morocco. It has been underpinned by principles that successive governments have adhered to since independence. These include commitments to African integration and unity, respect for the United Nations Charter and international law, and promoting regional stability.

Equally important have been pragmatism and non-exclusivity in bilateral and multilateral relations. This means Senegal is open to relations with all countries and partners to the extent that they further its national interests. While these principles may guide the Faye government, current issues and contexts could result in particular policy changes.

Economic considerations

An important area is the economic dimensions of Senegal’s external relations. The ruling coalition’s programme calls for left-wing Pan-Africanist policies ensuring greater national ownership and management of national resources. In keeping with this, Faye announced an audit of the oil, gas and mining sectors in his first speech. New Energy and Mines Minister Birame Souleye Diop reinforced this by indicating that existing contracts could be renegotiated on completion of the audit.

This comes against the backdrop of popular misgivings that some of these contracts weren’t negotiated in the interest of Senegal and wouldn’t benefit ordinary citizens. External partners and investors could therefore expect some form of economic nationalism.

However, a more cautious approach to the CFA franc’s future and Senegal’s membership of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (Waemu) could be expected. Both Faye and Sonko had criticised the lack of monetary sovereignty.

The country’s currency, used by seven other Waemu members, is pegged to the euro, and the Dakar-based central bank (BCEAO) conducts monetary policy. Faye and Sonko previously advocated for an exit from what they considered the tutelage of France over the BCEAO, and replacing the CFA franc with a currency that would better benefit local economies.

Sonko clarified his stance in a pre-election press conference, saying a new currency would be introduced only if CFA franc reforms at the sub-regional level failed. His appointment of Abdourahmane Sarr — an economist known for his reformist stance on the currency — as Economy, Planning and Cooperation Minister, signals his intent to pursue reform. However, there is awareness of a replacement currency’s complexities and potential consequences, including managing exchange rates and inflationary impacts.

Similarly, significant shifts in regional engagements appear unlikely. Senegal is an active Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas) member and considers the bloc an important partner in ensuring regional stability, especially in neighbouring Guinea-Bissau and Gambia. These two countries, which border Senegal’s southern Casamance region, are crucial to finding a definitive solution to the region’s long-standing conflict.

Security contribution

This partly explains Senegal’s support to the Ecowas Mission in The Gambia, despite growing weariness among some Gambians, and its troop contribution to the bloc’s Stabilisation Support Mission in Guinea-Bissau. Senegal’s new authorities will have to strengthen relations not only between states but also among populations.

Security and economic benefits, including access to a West African market of about 394 million people, means a weak Ecowas isn’t beneficial to Senegal. In fact, the ruling coalition has committed to reforming the bloc’s institutions to make them inclusive of its people.

Supporting a stronger Ecowas means Senegal can help bring Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger back into the regional institution. The three countries formed the Alliance of Sahelian States in September 2023 and in January withdrew from Ecowas over its handling of their coups.

Sonko has in the past expressed support for Mali’s interim leader Assimi Goïta, and Senegal’s new leaders share the Pan-Africanist and sovereignist ideals of their Sahelian counterparts. Despite this, the country’s triumphant election confirmed its status as a strong democracy, making a union with the military-led countries unlikely.

The three Sahelian states were invited to Faye’s inauguration — showing the president’s interest in keeping relations cordial while working on Ecowas reforms, and possibly helping create conditions for their return. These engagements don’t mean Senegal will replicate the Alliance of Sahelian States’ strong ties with actors such as Russia, or terminate security cooperation with existing partners. France, the US and European Union have supported Senegalese defence and security forces over the past decades.

Senegal will probably remain pragmatic by sustaining relations with its traditional partners, expanding existing ones and building new ties. This can be done while being sensitive to anti-imperialist and Pan-Africanist sentiments among a mostly youthful population. DM

Sampson Kwarkye, Project Manager and Aïssatou Kanté, Researcher, Littoral West African States, Institute for Security Studies (ISS) Regional Office for West Africa, the Sahel and Lake Chad Basin.

Research for this article was funded by the governments of Denmark, Norway and Sweden, and the Bosch Foundation.

First published by ISS Today.

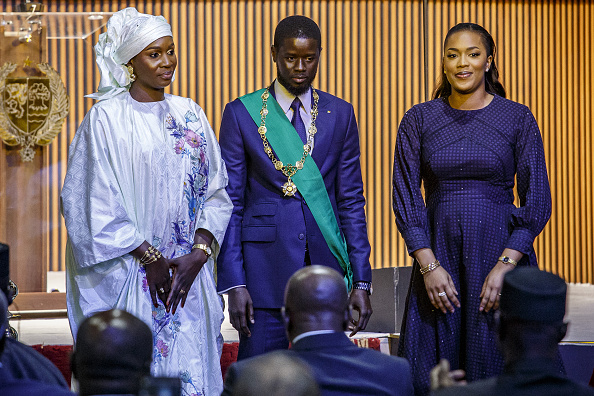

Bassirou Diomaye Faye, Senegal’s president, with his two wives during his inauguration ceremony in Diamniadio, Senegal. 2 April 2024. (Photo: Annika Hammerschlag/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Bassirou Diomaye Faye, Senegal’s president, with his two wives during his inauguration ceremony in Diamniadio, Senegal. 2 April 2024. (Photo: Annika Hammerschlag/Bloomberg via Getty Images)