BOOKS

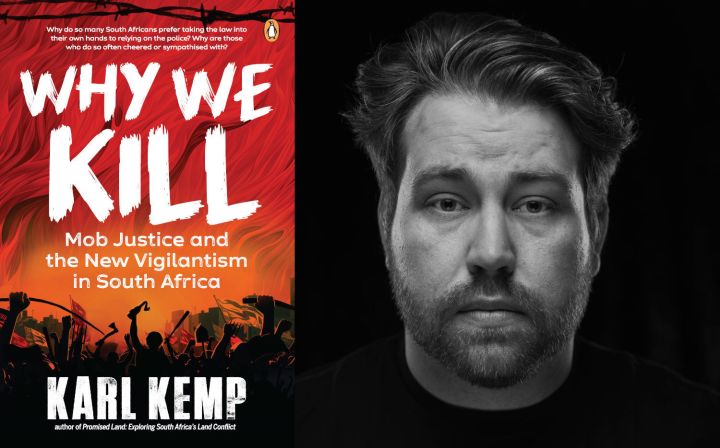

‘Why We Kill: Mob Justice and the New Vigilantism in South Africa’: lawless judgments

In ‘Why We Kill’, Karl Kemp explores why so many South Africans would sooner take the law into their own hands than rely on the police. And why those who do so are often applauded or sympathised with.

Of the unprecedented 27,000 recorded murders in South Africa in 2022, at least 1,894 — or 7% — were attributed to mob justice and vigilantism. That’s more than double the number from five years earlier.

In the first nine months of 2023, a further 1,472 mob justice deaths had been registered.

Mob justice is nothing new, but in recent years it has taken on an undeniably desperate and furious edge.

From the breathtakingly violent Zandspruit massacre in May 2021 to the killings during the July unrest two months later, to Operation Dudula’s march across the nation in 2022, vigilantism — and the condoning of it — has never before captured South Africa’s zeitgeist so sharply.

What has changed in the past few years, and what does it augur for the future?

Following three recent cases of mob justice, from the hellish metropolitan townships of Gauteng to the remote bushveld of northern Limpopo — and drawing on extensive research and interviews — Why We Kill explores the roots, realities and consequences of South Africa’s crisis of vigilantism.

Read an excerpt from the book.

***

It was a Sunday, Thabiso recalled. He knew this for a fact, as he and Calvin were watching the Sunday eight o’clock movie on M-Net when three young men came calling at the house. He knew at least two, had played soccer against one of them. The third, the stranger, had gold teeth and was the tallest of the three.

The trio accosted Calvin, who had answered the knock at the door. They asked to speak with Zita. They were insistent, and so Calvin woke the gogo. They sat in the living room and greeted the old lady, but refused to shake her proffered hand. They explained to Zita that they had come there ‘with problems’: Calvin had been implicated in a robbery. They asked her to join them outside, where they popped the boot of the car in which they had arrived to show Zita a beaten, blubbering man. She had never seen this man before, but that was not enough to stave off her grandson’s fate.

Calvin, the three young men told Zita, was being taken for interrogation. He would be returned to her.

They would make good on their promise.

Vinny, Gilly, Jappie and Samson – Vincent Lebese, Gilbert Lebese, Samuel Lebese and Samson Maruma, to name them truly – were locals in broader Soshanguve. Young township men, raised in the violence and uncertainty of post-apartheid South Africa. Gilly was all of twenty years old, Jappie somewhat older at twenty-seven, Samson twenty-six. It was Vinny, Jappie and Samson who took Calvin away.

Vinny and Gilly’s biological mother, Salphina, worked as a lunch lady at a local school. Jappie was their cousin, though just as often referred to as another Lebese son, much like Calvin and Thabiso were considered brothers. Their father, Victor Lebese, was an elderly man, working as a messenger. Samson was Vinny’s homie.

It so happened that one weekend, Mr Lebese was mugged on his way home from work – assaulted and robbed of his wallet and a bag of vegetables. Mr Lebese never reported the robbery to the police. He hadn’t bothered, for reasons known only to him and every other South African who prefers private justice to the type in which the state trades.

Instead, two days after the fact, his boys went out. On their version, they’d gone to the shops after a game of soccer. Whatever the reason, they’d departed the Lebese home that day in Jappie’s Mazda and returned some time later with Thabo Mahlangu, a strapping middle-aged man. In court, the two victims were distinguished by their complexion, Calvin being possessed of a lighter skin tone. The Lebese boys testified that they’d simply come across Thabo at the spaza shop. Apparently, the darker man was wearing the exact same clothes he’d been wearing when he robbed their father – so they nabbed him.

He was bundled into the car, driven back to the house and deposited before Mr Lebese, who was drinking in the yard with several friends. Immediately, Thabo started apologising: ‘I am sorry madala, I am sorry.’ And: ‘I’m sorry. I did not know that he was Vincent’s father.’ Mr Lebese merely confirmed that yes, this fellow had robbed him. He proceeded to slap him once, before apparently returning indoors and leaving Mahlangu to his fate.

Vinny Lebese told the court that it had been Mr Lebese’s elderly friends who had initiated the assault that would end in double murder. Their names were Mr Nkomani, Mr Ramongale, Mr Sithole and Mr Ntule. They were the closest thing Thabo would get to a trial. At some point, they started beating him with hand and fist and foot. And while they beat him, they interrogated him: Where is the stolen contraband?

More people joined in, neighbours and passers-by, for no other apparent reason than bloodlust or boredom or both. And it was at the newcomers’ suggestion, and at the darker man’s confession, that the sport was ceased for the second offender to be joined in proceedings. Thabo was locked in the Mazda’s boot to prevent his escape during the hunt for his alleged co-accused, young Calvin Ndlovu.

The crowd had swelled by the time Calvin was retrieved. Mrs Lebese stated that it ‘was now fuller because they were making noise’. The commotion had drawn in even more participants. Calvin and Thabo were dragged from the car. When they were brought before the mob, Thabo started blubbering ‘I am sorry’ over and over again.

The clock had struck 22:00. The yard was dark, for there were no lights in the streets or in the Lebese house. Mrs Lebese recounted that proceedings had been illuminated by the light of the moon. And it was under the light of that bright moon that Calvin and Thabo were set upon, whipped with a hosepipe that had been cut into sections – the same one Mrs Lebese had used earlier that day to water the yard – kicked and punched and stomped and stoned. As Mrs Lebese later told the court, ‘Everybody could use whatever they wanted to use.’

By her count, around eight people took part. The witnesses were inconsistent on this point, however – Mrs Lebese stated that she could not be sure because ‘there were many people since my house is at the corner and there is a street that is passing along and there are some few houses surrounding that corner and when people hear something they rush to that place. So there were so many people.’

Jappie, who testified that he had waited in the car during the beatings, as he was having an argument with his girlfriend over the phone, was asked by the prosecution whether he had seen the two victims being dragged into the yard. He answered in the negative, but added: ‘I can say I saw them, because they were screaming. The deceased were screaming.’

The next morning, Mrs Lebese woke as usual. She must have assumed that Calvin and Thabo had been taken care of. Vinny told the court that the pair had ‘left on their own’; that they could ‘speak and talk, they were fine, they were not injured’.

In fact, Thabo’s body – like Calvin’s, naked save for ‘a Jockey’ – lay fifty metres from the yard in a patch of scrub. Presumably, that is how far the man was able to crawl before dying. The Lebeses had slept through the night with the corpse virtually on their doorstep. Calvin, as we know, had been declared dead some hours earlier at hospital.

A neighbour, a man named Simon Songo, called the cops to report Thabo’s dead body, which he’d discovered that morning. Little did he know how that one call would change the course of his life. We will come to his story later.

The Lebese boys swore to the court that they had tried to stop the beatings. Said Vinny under oath: ‘We started fighting them to let them go so that they can go on their own. Our intention was that after my father identified them we were going to take them to the police station, but since the people had assaulted them we decided to let them go. That is all.’

When the prosecution put to Vinny that they could have taken the two men to the station after they had been beaten, he responded, ‘Because we realised that they were assaulted, we let them go.’

Jappie swore that he was on the phone to his girlfriend in the car throughout the incident. Gilly said that he had gone inside to watch a movie. Samson stated that he’d never in his life had gold teeth, and that he’d walked the block or so back to his own house before Calvin was retrieved. Stupidly, he swore that Gilly had gone with him.

It could be that the Lebeses’ mother’s testimony sealed their fate, more than their own inconsistencies, for she told the court, in a quavering, mystified tremor, that she knew her children. She’d seen them in the thick of it. Why would a mother lie about such a thing, after all?

But perhaps it was another admission – possibly blurted in the heat of the moment – that swung the court in the direction of conviction. Under cross-examination, Samson was asked by the prosecution what interest he’d had in the matter – ‘it is not your father that was robbed’. And Samson had replied:

Normally, when people do something to us, if they commit a crime there in the village, and we go to report them, they just disappear. For example, there was somebody who we caught red-handed in my brother’s house. We went to the police station and opened a case and after two days he was out again.

In other words, the South African Police Service (SAPS) could not be trusted to do what had to be done. True justice would not be forthcoming from the state. With that statement, Samson may as well have written the judgment himself.

***

It was never determined whether Calvin had in fact taken part in the mugging of Victor Lebese. Such detail is unimportant. Calvin Ndlovu and Thabo Mahlangu were the recipients of what, in South Africa, is colloquially called ‘mob justice’.

There are common elements to such incidents, markers along a gradual progression to the killing blow. The fact that the kill may or may not have been intentional. The court of the elders – less frequent nowadays, as we will see. The humiliation and degradation of the victim. The gleeful participation of neighbours. The way the killing sweeps up all who enter its orbit, whether as participants or spectators, and the way the justice system is constructed to swallow up as many of them as possible.

The little whispering voice that asks whether it is so bad to murder criminals in a country with a crime rate like that of South Africa.

The prosecutor – whether to draw out inconsistencies and lies, or out of bewilderment or affront at the disregard with which his house was held by the masses – drew a bead on the four accused in respect of their failure to involve the SAPS.

Time and again he asked, Why didn’t you go to the cops? And apart from Samson’s ill-advised disclosure, no one gave answers. They didn’t have to. Wander into a square populated by a broad cross-section of South Africans and ask this question, and most will tell you: Because they are useless. And by that mantra, hundreds are murdered every year, rather than being tossed into the sluggish and overburdened criminal justice system.

For vigilantism is as much a part of South Africa’s endemic culture of violence as the crime and incompetence to which it is a response. DM

Why We Kill: Mob Justice and the New Vigilantism in South Africa by Karl Kemp is published by Penguin Random House SA (R350). Visit The Reading List for South African book news, daily – including excerpts!

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.