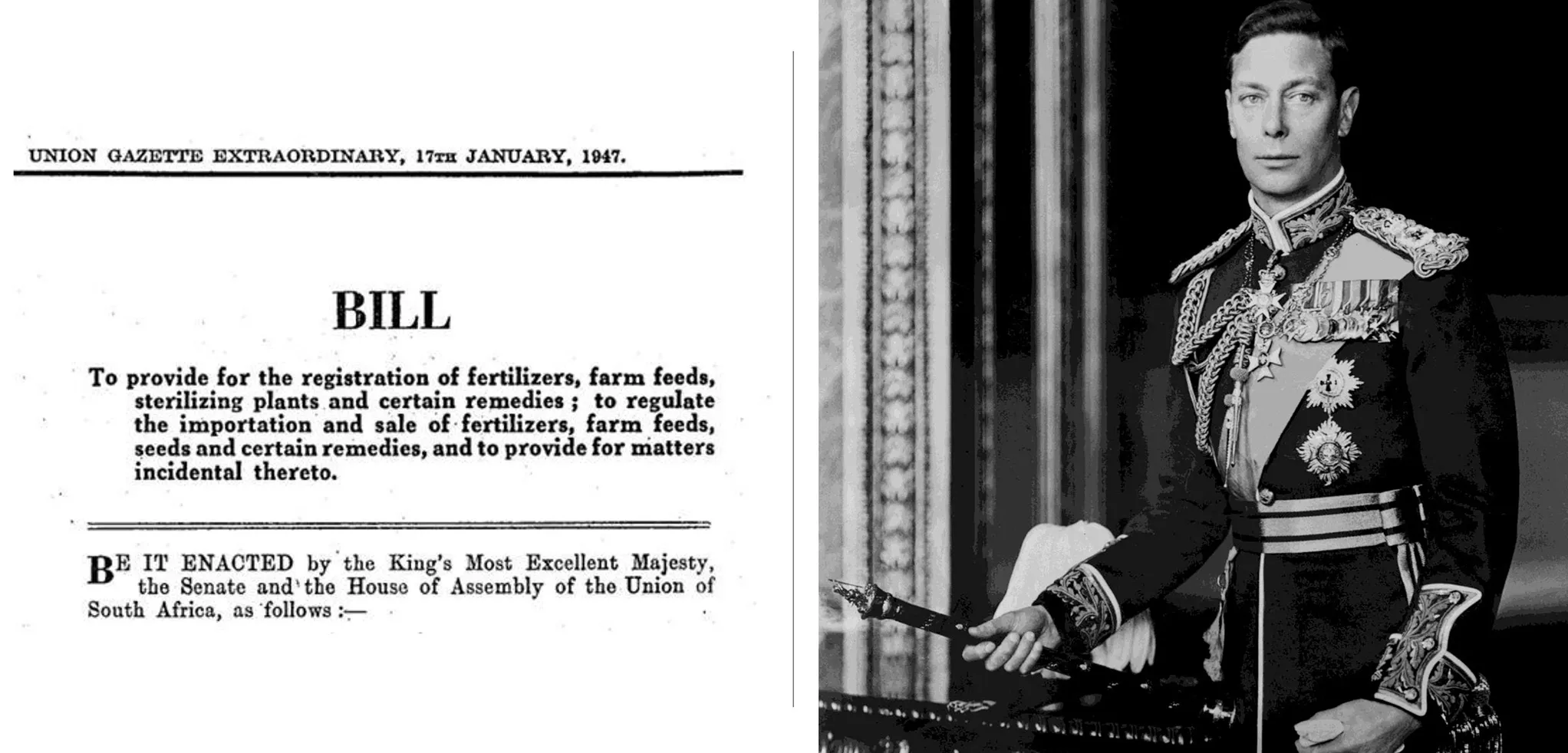

It has been 77 years since the first law to regulate chemical pesticide safety was passed in this country. This was back in the days of King George VI, Jan Smuts and the Union of South Africa.

Since then, South Africa has become the largest consumer of pesticides in Africa, accounting for roughly a third of all farm chemicals used on the continent.

Remarkably, however, the enduring influence of antiquated legislation to control toxic pesticide formulations can still be found in the latest version of the Fertilizers, Farm Feeds, Seeds and Agricultural Remedies Act of 1947.

Here is one example: The current Act still specifies a fine of “£500” for government officials who unlawfully disclose any confidential business affairs of the agricultural industry.

Juxtaposed against this £500 fine (roughly R12,000 at today’s exchange rate), the current version of the Act only permits a maximum penalty of R1,000 for violations of the country’s main pesticide control law.

The Adjustment of Fines Act of 1991 does provide for a retrospective stiffening of fines using a ratio determined by periodic government notices, so the R1,000 fine may now be closer to R80,000.

Nevertheless, the £500 fine crafted to protect industry secrecy and the derisory scale of maximum fines for pesticide law violations, remain on South Africa’s statute book – stark evidence of an outdated legal legacy and powerful influence of vested industry interests in an era where modern agricultural systems seemingly remain addicted to chemical poisons to sustain the growth of food or cash crops.

As evidence continues to pile up about the serious harm to humanity and the environment from the increasing volumes of pesticides sprayed across the world, the government has failed to implement a series of reforms recommended by its own policy document – the “new” Pesticide Management Policy published 14 years ago.

There has also been a two-decade delay in passing domestic laws to enforce the Rotterdam Convention, an international treaty ratified by South Africa in 2002 to limit the global movement of banned or severely restricted pesticides.

It was only in May 2021 that Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment Minister Barbara Creecy gazetted new Rotterdam domestic regulations, which introduced new penalties of up to R5-million for pesticide manufacturers and distributors who either import or export hazardous chemical and pesticide formulations in contravention of the international treaty obligations.

But in November 2021, Creecy changed her mind and suspended the implementation of the new regulations for 12 months. Following a further series of delays, she has since repealed the original regulations and published a new version that is only due to take effect in mid-June 2024 (barring further delays).

Creecy’s department has rejected claims of any improper influence from the agrochemicals industry in delaying the new Rotterdam domestic regulations and attributed some of the delays to “substantive” objections that included the apparent omission of CAS chemical registry numbers from the published regulations.

Croplife SA, an industry body whose members include agrochemical companies such as BASF, Bayer, Corteva, UPL and Syngenta, says it is also “not of the opinion that Minister Creecy is intentionally delaying the implementation, but rather ensuring that the regulations are free of errors, which is of paramount importance”.

Nevertheless, documents on its website suggest that it is pushing back against international pressure to phase out at least 29 chemical substances linked to greater risks of cancer, genetic damage and other harms to people, animals and the environment.

At a series of workshops last May for farmers, government officials and journalists, senior Croplife leaders said there was a need to “bring the African narrative more firmly into relevant policy discussions” around the European Green Deal – a recent initiative to protect human health and restore damaged ecosystems. This includes plans to reduce use of the most hazardous pesticide types by 50% by 2030.

According to European Health and Food Safety commissioner Stella Kyriakides: “It is time to change course on how we use pesticides in the EU … We need to reduce the use of chemical pesticides to protect our soil, air and food, and ultimately the health of our citizens. For the first time, we will ban the use of pesticides in public gardens and playgrounds, ensuring that we are all far less exposed in our daily lives.”

According to a European Commission “Farm to Fork” policy document, EU scientific advisers have concluded that the current food system in Europe is no longer sustainable.

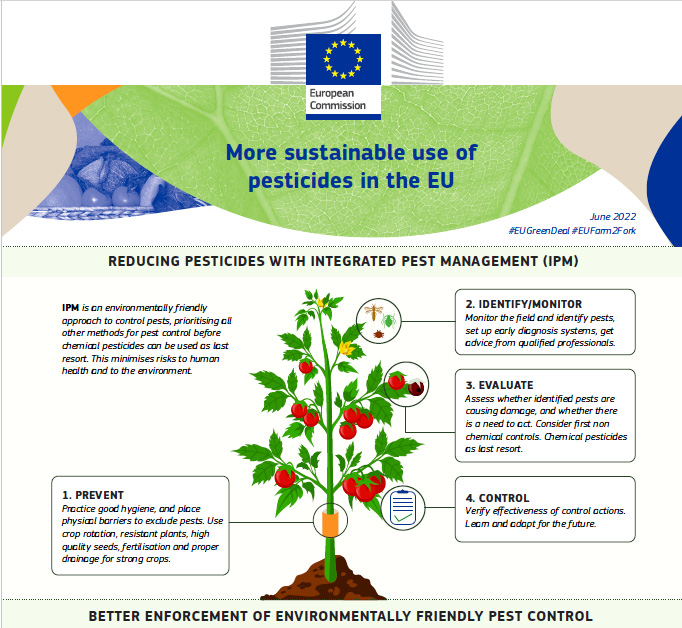

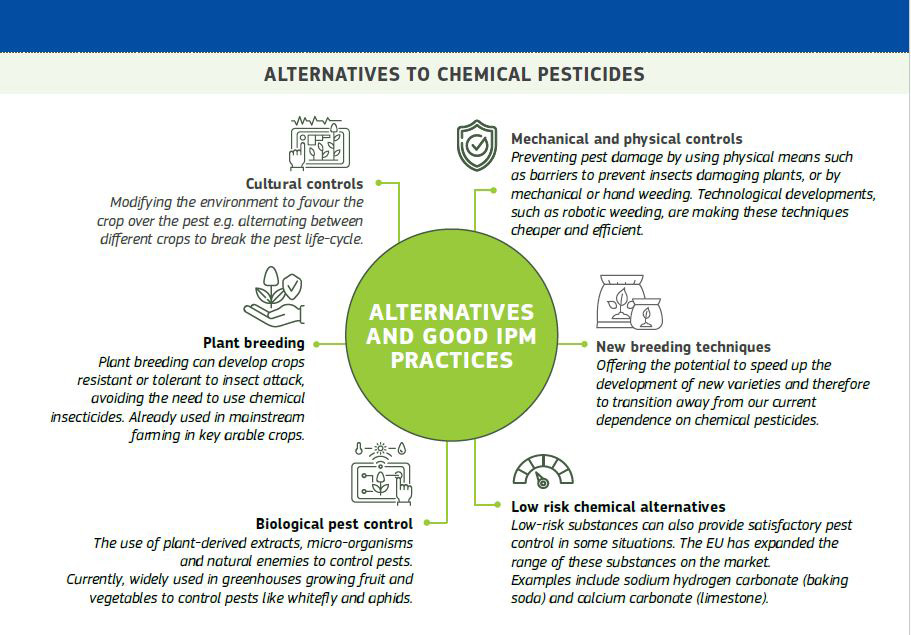

“This does not mean that pesticides are not needed. There are cases where satisfactory pest control can only be achieved in commercial food production through the use of chemical pesticides. However, chemical pesticides should be used only as a last resort.”

The commission also cites a World Health Organisation report which estimates that there are about 1 million cases of unintentional pesticide poisonings every year, leading to approximately 20,000 deaths. A more recent review estimated about 385 million cases of unintentional acute pesticide poisonings occur annually worldwide, including around 11,000 fatalities.

Chemically active pesticides were found in up to 30% of European rivers and lakes, and regulators are worried about the increasing impact on the pollination of food crops at a time when up to 10% of bee and butterfly species in Europe are on the verge of extinction, and 33% are in decline.

Croplife SA has made it clear that it will push back against so-called EU “mirror clauses” that would prohibit South African farmers from using certain pesticides if they export products to Europe – even if these pesticides are legally registered in South Africa.

Global pesticide distributors have frequently been accused of double standards, by peddling in African and other developing countries agrochemical products that have been either banned or severely restricted in Europe because of human safety and environmental concerns.

Croplife SA, however, responds that enforcing European policies on local farmers is a “threat to the government’s right to make decisions for its people based on the local conditions and requirements”.

“Products cannot just be ‘dumped’ in South Africa as some activists claim; they must go through a rigorous registration process that considers the local production conditions and environmental impact.”

Croplife insists that the current regulatory framework in South Africa remains “robust” and “very strong” even though the original Act dates back to 1947.

But that is not how several other interest groups view the 1947 pesticides control law.

Prof Leslie London, a senior University of Cape Town (UCT) public health research expert on pesticide hazards, chemical neurotoxicity and farm worker safety, says: “I think what Croplife really mean is that South Africa has a regulatory environment very favourable to industry. It would be laughable to consider it ‘strong’ unless you mean strongly biased to industry.”

He argues that at a time when many developed countries are adopting policies that promote pesticide reduction, South African policy remains largely out of step with international concerns

The primary 1947 law to control pesticides is regulated by the national Agriculture department, via the Registrar for Pesticides. But because this department is also mandated to promote agricultural expansion, Prof London believes this creates a clear conflict of interest concerning independent pesticide regulation.

He also suggests that the national department has done little to promote the Integrated Pest Management philosophy, which encourages farmers to reduce their reliance on chemical pesticides.

In a journal critique published in 2000, Prof London and fellow UCT public health researcher Prof Hanna-Andrea Rother argued that pesticide regulation fines were “grossly inconsistent with the gravity of offences” while inspectorates were hugely understaffed.

Nearly a quarter of a century later, those derisory fines remain unchanged, and Prof London says that though there has been some “tinkering”, the current pesticide regulation model remains more or less unchanged.

He suggests that South Africa is still locked in a “pesticide culture” that sees intensive chemical control of farm pests as the norm, rather than as a last resort.

“This consent is manufactured by many forces, economic and ideological, and can be seen in the nature of pesticide advertising, and discourses surrounding the heroic role pesticides can play in economic development in the new South Africa,” according to the two researchers..

They noted that 100 to 200 cases of pesticide poisoning were reported every year to the Department of Health (mostly farmworkers or rural residents), while other surveys suggested that the true rates were anything between five and 20 times higher.

To resolve conflicts of interest and the fragmentation of regulation, the two researchers call for a new independent regulatory body to act as guardian of the public interest, separated from the economic motive to promote agricultural production.

Similar proposals for reform have also been made by Advocate Susannah Cowen SC on behalf of the Real Thing natural health products company.

In a legal opinion submitted to the SA Law Reform Commission in 2021, Cowen draws attention to the apparent double standards of South Africa importing hazardous chemicals from countries where these same chemicals are banned.

Cowen (now a judge of the labour court) said: “No amount of tinkering or amendment can render the 1947 Act fit for purpose in a democratic South Africa. It is wholly outdated.”

At the time of the submission, she said there was also no requirement for periodic safety reviews of currently registered pesticides or re-evaluations of old chemicals.

“The State made important reform commitments in the Pesticide Management Policy for South Africa in 2010. However, these commitments have not been realised and very little has been done since 2010 when these commitments were made.” DM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fMctVju6FuA

The Department of Agriculture Land Reform and Rural Development responds:

“The (1947) Act may only be amended once its relevance, applicability, suitability and responsiveness is under question, and so far the Act is still potently applicable

“Over the years, the department has phased out or banned many pesticides of concern under the same Act. We will continue to review the pesticides on concern, and where applicable we will phase out or ban them.

“There have been several regulations under the Act which the Minister has made in order to respond to some substantive recommendations which were part of the 2010 Pesticide Management Policy. The regulations relating to agricultural remedy, as published in Government Notice No. R. 3812 of August 2023, are aimed at addressing the recommendations of the 2010 Pesticide Management Policy.

“The latest regulations were published on 25 August 2023, which, among others, are aimed as phasing active ingredients and their pesticides formulations that potentially may cause cancer, genetic mutation and damages to fertility of a human being (including negatively affecting the unborn child); implementation of the Globally Harmonised System of classification and labelling of chemicals; restrictions of sale and use of certain hazardous pesticides, disclosure by agrochemical companies of amounts the of pesticides sold and other measures.

The Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE) responds:

A spokesperson said the department “categorically rejects [suggestions] that it has taken 20 years to implement the Rotterdam Convention. DFFE has been facilitating the exchange of information for more than 17 years (as far back as 2006).”

Commenting on the reasons for a recent series of notices to suspend, repeal or amend the convention’s domestic regulations, the department said it was compelled by law to undertake public participation when developing regulations.

“There were submissions on substantive matters that were submitted after the finalisation of the (Rotterdam) PIC Regulations that influenced the department to reconsider and opt for the suspension of the PIC Regulations. The department rejects claims or any perceptions of improper influence and maintains that the Batho Pele principles of consultation, courtesy and responsiveness remained at the centre of the department’s decision to suspend the regulations while the specific amendments were being attended to.”

Croplife South Africa responds:

Croplife confirmed that it made submissions to Creecy’s department to correct certain errors in the registration status of chemicals listed in the Rotterdam regulations.

Responding to criticism about the “double standards” of selling pesticides in Africa when they were banned in Europe or other developed nations, Croplife said: “It is quite normal for some countries to have plant protection solutions authorised for local use when they are not registered in other countries. Local climatic conditions, pest occurrence, crops and regulatory procedures differ from country to country. Therefore, products can be registered in one country and not in another.”

The industry group acknowledged that current laws only provide for a R1,000 fine for contraventions of the 1947 Act, but noted the government could impose much more severe sanctions – such as a banning or cancelling sales of certain chemical products.

There had also been “several” amendments since 1947, while specific product registrations were reviewed every three years.

New regulations published in August 2023 also contained a clause that a pesticide registration holder was obliged to inform the registrar of any new data pertaining to environmental or human toxicology

“Act No 36 and its supporting regulations provide a robust regulatory framework for plant protection solutions in South Africa. As with any government department, the Act No 36 of 1947 regulatory team could be more efficient if central Treasury provided greater funding. In this way, the approval and registration process could bring newer technologies to South African farmers more quickly.

“Government still has the overall right to approve or not approve a product. But our opinion remains that the system for product registrations can be more efficient, bringing newer technologies to farmers quicker, by better utilising the fees already paid to government for product registrations”.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=REeWvTRUpMk

The South African Compendium on Pesticides is a comprehensive database listing more than 100 papers produced over 20 years. (Photo: schmidtlaw.com / Wikipedia)

The South African Compendium on Pesticides is a comprehensive database listing more than 100 papers produced over 20 years. (Photo: schmidtlaw.com / Wikipedia)