BOOK REVIEWS

The lion’s scientist and the lion’s historian track historical and natural spoor

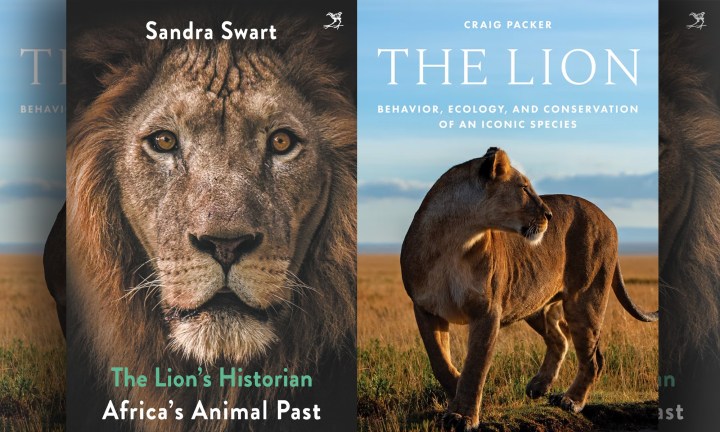

Two recent books, one by a top US scientist, the other by a leading local historian, open new windows into our understanding of lions and more widely Africa’s arresting animal past, present and future. Together, they widen the lens that science and history cast on the veld, connecting the dots between the two.

“Until the lion has a historian of his own, the tale of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”

This is a proverb that the late, great Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe recalled, and the lion now has its historian in Sandra Swart, chair of the Department of History at Stellenbosch University.

In The Lion’s Historian: Africa’s Animal Past Swart tracks the historical spoor of animals – wild, domestic and feral – and their interactions with people in southern Africa, opening new paths into our understanding of the history of both. (To read an excerpt, click here).

Swart’s insightful work is a fitting companion to another recent book by the lion’s scientist. Craig Packer of the University of Minnesota is widely regarded as the world’s foremost expert on the big cats. The Lion: Behavior, Ecology and Conservation of an Iconic Species takes readers on an engaging journey through the science that has unlocked many of the mysteries of the pride.

The relations between humans and animals, how these have evolved, and how they have swayed the course of history have long been a subject of historical enquiry, including by perceptive non-historians such as Jared Diamond, an ornithologist by training.

His 1997 work, Guns, Germs and Steel, explored, among other things, how the handful of species that were suitable for domestication ultimately gave Eurasia a comparative advantage in the development of things such as agriculture and warfare. Africa, by contrast, was burdened by beasts which could not be domesticated, and became the last great refuge of the planet’s megafauna after human hunters and climate change exterminated most of large mammals on a global scale during the Pleistocene.

The pioneering work in the 1980s of environmental historians such as Alfred Crosby — the author of Ecological Imperialism and the Biological Expansion of Europe, 900-1900 – also raised the profile of animals in history. Other examples include Man and the Natural World: Changing Attitudes in England, 1500-1800, an early 1980s book by master historian Keith Thomas.

What such works have in common perhaps is a focus on the role that animals played in human history and also – especially in the case of Thomas – how the image of animals evolved in the human mind.

Swart, like these scholars, uses the insightful prism of the longue durée – or the “long term” – a historical approach linked to the Annales school of thought and historians such as Fernand Braudel. It is also an approach that connects the historical dots in often unexpected and revealing ways.

But Swart also follows the trails blazed by previous scholars into new terrain which sheds a torch light on deep history and brings to life concepts such as animal agency, culture and history.

“Both lions and humans are products of history. Individual lions are known; they have stories. To some trackers, their unique histories are evident in the very spoor they leave. Tracking is an ancient art and it is much more than merely counting or finding an animal. Tracking is fundamentally the historical reconstruction of creaturely identity and their past activity, a process that takes animal agency seriously… tracking was arguably the earliest kind of historical study that humans ever attempted. Perhaps animal history is thus not a new kind of history but our very oldest kind,” she writes.

From these ancient roots, Swart suggests new ways to spread the canopy across the veld of 21st-century historiography.

“Adding ‘species’ to ‘race, class and gender’ may change our historical understanding. It may even deepen our understanding of what it means to be human,” she argues.

“We need to write histories taking a broader view beyond that of the hunter. We need accounts that connect deep history to the present moment. We need stories in which gender and generational context are not forgotten. These new histories will allow us to understand our own past as more complete in a multispecies and more-than-human context.”

To this end, Swart deftly employs species as a tool for historical understanding. Lions of course but also ants, baboons and elephants are among the animals covered. For this review, I’ll focus on Swart’s examination of domesticated animals, which it turns out is rich grazing for a historian.

Take the example of cattle. In much of Africa, cattle are venerated and regarded as a key measure of wealth. This reviewer has raised the notion before in Daily Maverick that this makes sense in Africa’s fearsome faunal environment. Here is something that stands out in shimmering contrast to an often menacing menagerie: A mammal that is large, mostly docile and useful.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Africa’s beastly burden: The case for shrinking the faunal poverty line

Swart places cattle – and livestock more widely – on a number of historical stages in South Africa, starting with Johan Anthoniszoon “Jan” van Riebeeck and the initial mid-17th century European settlement of the Cape.

“The relationship between settler and local population pivoted on access to animals,” she writes. “Animals were the most significant article of trade and were the key signifier in the shifting relationship between settlers and indigenous groups.”

The Dutch regarded livestock as property that could be translated into capital, used for barter, or regularly converted into calories through slaughter for meat. This rubbed against the grain of Khoekhoe conceptions of livestock as a source of milk and only occasionally as one for meat.

This difference was initially lost on the Dutch, who “were baffled and alarmed by the refusal of the indigenes to sell their animals” and got played as a result.

“While no strangers to long-distance trade, the Khoekhoe were unaccustomed to large-scale trade in cattle, especially as their social cohesion was vested in and dependent on their livestock… However, the Khoe fairly rapidly understood what the Dutch craved and their own power in this trade relationship: The price of livestock shot up exponentially.”

And there are telling examples that livestock also had agency, with cattle choosing to follow Khoekhoe – familiar humans – rather than European herders in some of the instances in which exchange took place.

“It was difficult for the settlers to ‘take stock’, either literally or metaphorically,” Swart notes, “compelling the settlers to see animals in new ways.”

Indeed, “… an animal-sensitive history yields several surprises, exploding popular historical myths. It helps invert the triumphalist narrative of conquest… the settlers have been wrongly credited with knowledge and power they neither felt nor possessed. Knowing how the story ends has obscured how the story started. The shifting relationships in the first 10 years of contact pivoted on animals.

“The indigenous population arguably derived more benefit than the settlers from the uneven power dynamic in the first few years before their dispossession.”

Swart also places livestock at the centre of the 1913 Natives Land Act, which triggered dispossession on a grand scale with unresolved consequences and conflicts that still haunt South Africa’s political, social and indeed faunal landscape – think, for example, of the challenge presented by overgrazing in the former homelands.

This brings us to “the politics of species and race” and Sol Plaatje’s observation that “… it is as bad to be a black man’s animal as it is to be a black man”.

Swart writes: “Up until now, historians focused on the iniquitous land aspect of the law… The Act’s outcome (in some places) was to harness the skills of the black tenant farmers and tie their resources (especially oxen) to their white landlords. So both Africans and their animals were yoked into servitude… analysis has ignored one of the key historical role-players: the animals.”

For Plaatje – the first general secretary of the South African Native National Congress, which morphed into the African National Congress – cattle were vital to his Tswana culture. And they figure prominently in his famous polemic, Native Life in South Africa.

One of the act’s upshots was to deprive Africans and their cattle herds access to prime grazing grounds, leading to a fast sell-off of the starving animals which white speculators cashed in on. It was, Swart notes, “a multispecies tragedy” which touched a raw nerve in Plaatje.

Swart draws attention to “the visceral horror experienced by both halves of Plaatje – a Tswana man and a middle-class British subject – at the sight of skeletal herds and flocks needlessly starving to death”.

The “middle-class British subject” in Plaatje reflected the animal welfare movement and the growing British aversion to animal cruelty, a subject covered in the Keith Thomas text mentioned above. Indeed, a fact that is fairly widely known in social history circles but not the general public is that British animal anti-cruelty campaigns preceded those focused on children.

The horse also gallops into this history and “Van Riebeeck was darkly gratified when the local clans seemed suitably awed by his horses. This was to lay the foundation of the use of horses in southern Africa as integral to symbolic displays of power, which persists all the way up to the modern day.”

But the empire would ride back and horses would become a tool of indigenous resistance. In the mountains of Lesotho, the species would become a symbol of highly gendered Basotho nationhood.

No work on animals and history in this neck of the woods would be complete without dogs, and Swart explores this issue in the chapter, “Apartheid’s Hounds: How South Africa Invented the World’s Most Terrifying Police Dog”.

Perceptions of canines are among the wider cultural divides between black and white South Africans on the faunal front, and were thrown into sharp relief during the initial hard lockdown in March/April 2020 when dog walking was banned. And such divisions are a product of history.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Crying Wolf: Lockdown’s dog-walking issue has deep roots, revealing South Africa divisions

The dog’s wild ancestor is the wolf. Not native to Africa, the wolf is the snarling exception to one of Diamond’s general rules about an animal’s suitability for domestication – a benign disposition – a trait not commonly associated with Canis lupus.

In the early 20th century, Swart highlights the uncanny ability of South African police dogs – comprised after much experimenting with “a large pinch of Doberman pinscher with a dash of Rottweiler” – to extract confessions.

“It is striking how, time after time, suspects would spontaneously confess after a police dog had tracked them,” Swart writes.

Swart sees three possible explanations for these canine-conceived confessions. One is that forensic science was still in its infancy, and for “alleged perpetrators, it simply seemed pointless to defy this new science”.

Another possibility is that confessions may have been the product of violence as the police themselves may have had faith in the “power of smell” and such tactics are hardly unknown among South Africa’s cops.

“A third reason was suggested at the time and believed by the top brass down: witchcraft,” Swart writes.

She concedes this may not have been the case, but goes on to say that “it is worth exploring for the light it casts, if not on what the public believed then, at least on what the police were thinking”.

Swart cites the historian Keith Shear, who suggested that police dogs may have assumed the art of “smelling out” linked to sangomas and nyangas.

“We must remember how prevalent witchcraft was in the first half of the 20th century. This was a time of social dislocation, political conquest, land dispossession, and strange diseases like rinderpest and influenza,” Swart writes.

But the emerging South African state misunderstood indigenous healing and spiritual views, outlawing such practices under the Witchcraft Suppression Act of 1910.

“These laws drove a wedge between white and black communities, as the latter argued that the state had actually aligned itself with witches,” Swart notes. And dogs would play a major role in this saga through their own tracking of spoor.

This reviewer would add that witchcraft belief endures in the 21st century in South Africa and elsewhere in Africa, and is still often associated with wild animal attacks on the continent. This is perhaps explained by the fact that such events can be seen as an intentional act of malice. And a dog is effectively a wolf in dog’s clothing.

***

Witchcraft does not figure in Packer’s book, but it is a subject that has captured his interest. He presented some of his findings on the matter in October 2023 at the annual Oppenheimer Research Conference.

I spoke with him afterwards, and he noted how if a series of attacks was believed to be the work of a “spirit lion” instead of the real thing, it robbed rural dwellers of agency because they regarded attempts to kill the beast as futile.

“Our data shows that when there are man-eating outbreaks that are believed to be spirit lions then there are twice as many victims because people wouldn’t do anything about it so the lions are free to keep catching people. If they thought that they were normal lions then they would organise some kind of response, they’d call the game officer or whatever,” Packer told me. Perhaps witchcraft will find its way into his next book.

In his most recent book, Packer notes that the lion requires little in the way of an introduction “… as our relationship with the species extends back for millennia. Our ancestors drew paintings of archaic lions on the walls of their caves, ancient civilisations portrayed lions as sphinxes (human-headed lions); griffins (half-lions, half-eagles); servants of the goddesses Ishtar and Parvati; and the vanquished foes of exalted Assyrian kings”.

“Many of us grew up with the lion as a character in children’s literature (the Cowardly Lion from the Wizard of Oz, Aslan from The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, Simba from The Lion King), and we often describe someone we admire as being brave as a lion, as having a leonine grace, as being lionhearted. But none of these portrayals tells us much about what it’s really like to be a lion.”

Indeed, the reality informed by science is far more arresting than the image of the lion spawned in the minds of humans, many of whom have never experienced one firsthand. Packer in this book seeks to set the record straight while acknowledging that the pride still holds secrets. This is the bait that keeps luring scientists – and historians as well.

The Lion is focused on the questions that Packer – who initially studied another social animal, the baboon, under Jane Goodall – and his colleagues sought to answer about the big cats through intensive studies over several decades in the Serengeti and Ngorongoro Crater in Tanzania and elsewhere.

Take the question of the cycles of the moon and its relationship to lion feeding patterns, including the consumption of humans by “man-eaters”.

“Lion attacks on humans are most common between sunset and moonrise during the first week after the full moon,” Packer writes.

This is a conclusion that Packer reached from scientific methods, measuring lion belly sizes and comparing this data with luminosity, while also examining the available data on the timing of attacks.

It is a finding that Packer the scientist also suggests can shed light on historical images of the moon.

“… the full moon accurately indicates that the risks of lion predation will increase dramatically in the following evenings, perhaps helping to explain the many myths and superstitions about the full moon.”

Packer also uses the historian’s lens to help explain man-eating outbreaks.

“The outbreak of man-eating in Tsavo closely followed the Great Rinderpest epizootic that struck East Africa in the 1890s and removed most of the lions’ natural prey, and the outbreak in southern Tanzania in the 1990s coincided with the loss of prey following widespread habitat conversion to subsistence farming,” Packer notes.

In Swart’s rendering, man-eaters are loosely akin to “social bandits” and “are useful (in exactly the same way as human outlaws) in letting us see normal human-animal relations in an unfamiliar and penetrating light, and in generating paperwork, leaving a trail in the archives where ordinary lions do not”.

That archive includes the lunar cycles.

Packer’s book also takes readers through the fieldwork and observations that sought to answer questions such as why lions have manes and why they are the only species of cat to have evolved into a truly social species.

On the question of the mane, “darker manes are… associated with better nutrition and higher testosterone levels. Dark-maned males are (also) more likely to survive wounding, they maintain pride residence for longer, and their offspring show higher survival in most circumstances.”

This makes dark-maned lions more attractive to females, a conclusion reached using life-sized toys (!) to draw their attention.

As to sociality, it seems the relative heterogeneity of savanna habitats and the population densities these give rise to have played a role. Swart would also see the uniqueness of “lion culture” at play here, which for some critics will be a debatable point, no doubt.

Taken together, this is a pair of books that deepens our historical and scientific understanding of African wildlife and Africans, providing plenty of food for thought as the moon rises in the sky. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.