BOOK REVIEW

Sandra Newman’s ‘Julia’ is a Nineteen Eighty-Four with a feminist twist

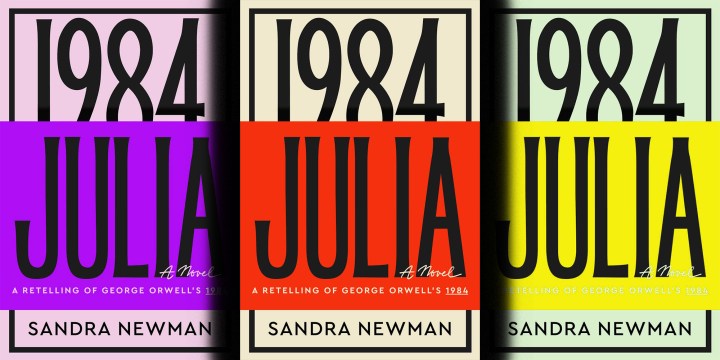

‘Julia’, Sandra Newman’s new novel, reframes George Orwell’s iconic dystopian story, placing the main female character of ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’ front and centre. But the infamous Room 101, the thought police, and Big Brother remain.

Almost from the moment it was published, George Orwell’s dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four became an international bestseller, as well as a literary talisman of resistance to the Soviet Union’s narrative of the future (even if that was too simple a reading of his novel and not totally what Orwell had in mind. The author was aiming at forces happening or likely to happen in many other nations as well, including his own.) Nevertheless, Nineteen Eighty-Four was a book that had come along at precisely the right moment for many, giving voice to their deepest fears about the future.

Probably almost everyone perusing this article has read that book (or at least pretended to in prep for their English classes in high school or university). Many millions of copies have been sold since its publication in 1949, just before Orwell’s death from tuberculosis. It remains in print still.

A fully engaged socialist during most of his adulthood, Orwell (born Eric Blair) was the child of a minor British imperial official — an opium inspection officer in British India and Burma. Orwell attended Eton on a scholarship, but instead of going to Oxford or Cambridge like most of his Eton classmates, he joined the British Indian Police — and not even the civil service.

But, after just one full tour of duty, Blair (he adopted the pseudonym of Orwell later) resigned due to his growing realisation of what he was on the road to becoming — a cog in the imperial machine, doing its dirty work out in the empire. After living rough, earning a spartan living doing menial jobs in Britain and France, he joined the POUM, the workers’ militia in the Spanish Civil War in Catalonia. (That experience gave him essential raw material for one of his most important non-fiction books, Homage to Catalonia).

He was now well on the way to building an increasingly influential career as a journalist, essayist and novelist — and a clear moral voice in Britain. Beyond reviling the imperial and capitalist order, his experiences in Spain also led to his disillusionment with communism’s inevitable totalitarian tilt. In Spain, the Communist Party there actively suppressed worker militias like the one he had enlisted in — and he and his wife, in fleeing to France, barely escaped arrest.

Returning to Britain, while his literary talents continued to gain supporters, during World War 2 he worked for the BBC Overseas Service to India, after he was rejected for military service on health grounds. Then, in the immediate aftermath of World War 2, he hit the literary jackpot with his short novel Animal Farm. It was a plain-speaking, but imaginative allegory in which a key phrase — “Some animals are more equal than others” — became an international watchword for opponents of authoritarianism everywhere.

It was translated into many languages (including by Western governments to distribute copies to wavering populations in central and eastern European nations seemingly headed toward communist governments). In subsequent years, it was rendered into stage plays and even turned into an animated cartoon. The force of its core has proved to be something almost impossible to avoid embracing.

Then, Animal Farm was followed by Orwell’s final novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four in 1949, only months before the author’s death. This novel, even more than Animal Farm, became a classic on par with the most prophetic dystopian novels. That company includes Jack London’s The Iron Heel, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, BF Skinner’s Walden Two, and Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower. (South African dystopian novels include JM Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians and The Life and Times of Michael K, Nadine Gordimer’s July’s People and Karel Schoeman’s Promised Land.)

Nineteen Eighty-Four delivered to its readers a Ministry of Truth (dedicated to rewriting history in accord with sudden changes in ruling party ideology and thus concocting lies), and perhaps most fearsomely, “Big Brother is watching.” That idea is taking on ever-greater relevance in our current age, with the intersection of advanced security techniques, electronic media, data capture tools and AI. The cumulative impact of such technological developments is generating an ever-present watchfulness by the state and business.

Orwell had despaired that such a confluence was imminent, even without the obvious jackboot-style authoritarian governance, and Nineteen Eighty-Four was his prophetic vision of this new totalitarianism once Nazi fascism had been vanquished and Soviet totalitarianism had then gained strength. It is just a guess, but he may have been proud to see how his prognostications had been realised, but, simultaneously, more despondent over how right he was, even after the collapse of the authoritarianism of the old Soviet Union.

Nineteen Eighty-Four ends with its everyman hero, Winston Smith — in the mould of many of his other fictional protagonists — broken by the power of the state and in thrall to his innermost fears. After mutual betrayals by Smith and his romantic partner, Julia Worthing, Smith finally embraces the seemingly implausible idea that he has come to love the oppressor, Big Brother, no matter what he says. It is a final triumph for the state — and the ultimate disaster for individualism.

But despite its vision and power, there is a flaw in Orwell’s greatest novel, echoing one running through much of his other fictional writing. Some critics have noted his male characters are vivid, multilayered and complex, yet his female ones are largely foils for the men in those stories, as with his portrayal of Smith and Julia’s relationship. Orwell’s male characters overcome, or are overcome, by circumstances — and, crucially, often due to their inner demons.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Best books of 2023 — a smorgasbord to tickle every literary tastebud

In recent years, some critics of Orwell’s work such as Anna Funder, the author of Wifedom (see The Guardian article on this controversy) have pointed out that with Orwell’s non-fiction reportage, the importance of his first wife, Eileen O’Shaughnessy, to his growing success has been sadly downplayed.

In response to considerations like that, Sandra Newman, a US novelist educated in the UK, at the encouragement of the George Orwell Trust that owns Orwell’s copyrights, undertook to flip this script on Nineteen Eighty-Four. Newman has put Julia Worthing and some of her female friends at the core of her new novel, while Winston Smith and other men have been moved into the roles of supporting characters. Yes, Smith is a useful sexual conquest, along with others, but he is not the flywheel driving Newman’s new novel, Julia. Newman has given Julia agency, free will and her own distinct destiny.

Unlike, say, a book like Scarlet, a dreadful successor to Gone With the Wind, Julia’s experiences, as depicted by Newman, largely stay within the timeline of what was in Orwell’s original dystopian universe — with its food rationing and ersatz beverages, and the shoddiness of housing and clothing. It is a sad place redolent of Cold War-era Romania, right along with the pervasiveness of the thought police. But for Julia, at the end of all her travails, there is also an O Henry-esque, deus ex machina that definitively rearranges the narrative.

In Newman’s hands, Julia’s life has more than a bit of an influence from Erica Jong’s 1973 novel Fear of Flying. But instead of Jong’s heroine’s middle-class, urban US life, Julia is set among the Orwellian (yet another gift to our contemporary language and thinking from Nineteen Eighty-Four) rubble of that incompetent, brutal, but flaccid socialism that is rife with corruption and brutality.

Different from Orwell’s vision, Julia’s world is one where sexual intimacy — with or without love — is one of the few alternatives left in life for people who yearn to push beyond boundaries even a little bit. This is in the face of a national campaign to stamp out sex, except in the service of giving birth by artificial insemination to future perfect citizens of Airstrip One (formerly Great Britain).

There are just enough homages to Orwell’s descriptions of life on Airstrip One in Julia that a reader is easily drawn into the world Orwell had earlier created. But in Newman’s hands, this is also a world largely without Orwell’s deep brooding sense that this is a world where history itself will end — and that life will be like this forever and ever. Amen. (See our earlier article on Orwell and George Kennan for insights into Orwell’s thinking.)

Newman has tweaked her narrative and the world within it just enough that Julia can move through a series of sexual liaisons in that world until things come crashing down around her. In the midst of this, she even warms to the idea, the temptations and the lucrative possibilities of further rewards once she agrees to become an informal, auxiliary member of the thought police. There, of course, is yet another one of Orwell’s inventions for this all-too-believable but alternate world.

For Orwell, as his novel concludes, beyond Winston Smith’s tortures and his and Julia’s mutual betrayals, the story ends with these words:

Forty years it had taken him to learn what kind of smile was hidden beneath the dark moustache. O cruel, needless misunderstanding! O stubborn, self-willed exile from the loving breast! Two gin-scented tears trickled down the sides of his nose. But it was all right, the struggle was finished. He had won the victory over himself. He loved Big Brother.

By contrast, following a picaresque escape from a London still controlled by Big Brother, Julia reaches the forces of the rebellion against the regime, as those rebels have taken over Big Brother’s headquarters in a new crystal palace in a greensward beyond London. Julia’s journey has become a version of Joseph Campbell’s idea that much fiction portrays a hero’s (or in this case, a heroine’s) journey towards personal redemption or success, following temptations, torments, challenges and choices.

For Newman’s heroine, in contrast to Nineteen Eighty-Four, a shocker of an ending comes (spoiler alert for future readers) as Julia discovers — at the moment of her liberation — that the new rulers whose camp she has joined have the same ideas about absolute party loyalty and subordination of self as the old regime. Regardless of whatever twists and turns the new party takes, no matter what violence it wishes its acolytes to inflict on its enemies, it is the same as the corrupt, violent mob it is replacing.

Newman closes the novel with Julia taking her oath of allegiance to the new leadership, an oath that mimics the old party:

“You are prepared to lose your identity and live out the rest of your life as another person?”

“Yes.”

“You are prepared to separate from everyone you know and never see them again?”

“Yes.”

“You are prepared to cheat, to forge, to blackmail, to corrupt the minds of children, to distribute habit-forming drugs, to encourage prostitution, to disseminate general diseases — to do anything which is likely to cause demoralization and weaken the power of the Party?”

“Yes,” said Julia. “Yes, I will.”

Here is the vital difference between the two versions of a possible future. For Orwell, his final novel is a warning about the true horror of a possible new order and the near impossibility for one human to evade its control once it is in place. Orwell’s book is a prophesy, a warning not to allow such a fate to become reality, lest it become impossible to bring it to an end.

By contrast, Newman seems to be saying that no matter who governs or what system of values they profess, in the end, it is all the same. If we buy into her conclusion in Julia, it is that we cannot escape oppression by a continuing series of tyrannies because governments are all, in the end, oppressors. That too is a warning, but it is one that demands a challenge that it is necessary for us to prove her thesis is wrong. It is possible to construct a government that is not as terrible as the one it has replaced. Progress is possible.

Just as Orwell’s novel became a vivid warning that totalitarianism must be faced down before it rules everything and everywhere, Newman’s book should evoke from readers the response: “You are wrong! Yes, there can be a better future, and not every system of government must become the same horrid nastinesses of the one that preceded it.” In this sense, Orwell’s book remains a retort to those who would say that all governments are the same, even as Newman’s novel seems to argue we can never escape the prison imposed upon us by any government — there is no hope; they are all the same.

This debate remains relevant for our contemporary world, what with ongoing challenges to Western liberal democratic values from many contesting authoritarian visions. This is true whether they are based upon religious fanaticism or from the coalescence of deeply intrusive social media, electronic tracking of every individual act or transaction, in tandem with government and private record-keeping carried to extremes. In this, Orwell’s warning remains vital, while Newman’s novel forces us to answer her charge. DM

Julia, by Sandra Newman, Granta Books, 2023, ISBN 978 1 78378 915 (hardback), ISBN 978 1 78378 918 4 (paperback), ISBN 978 1 78378 917 7 (ebook)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

We see the rules and regulations of Nineteen Eighty Four and Animal Farm being played out under ANC, SACP, and EFF domination. South African history is being re-written or, at least, transformed into doctrines of reverse racism against everything that the apartheid regime stood for. In essence the dogma of the ANC government in dictating that the standards of education be lowered to enable the less intelligent learners to achieve matric passes is resulting in the awful situation where over 80% of South African Grade 1 and 2 pupils are not being able to understand what they are reading. The levels of knowledge and intelligence in SA are thus being dragged down instead of being built up. The masses become more susceptible to manipulation and political control by the government. This will inevitably lead to Orwell’s “Some animals are more equal than others” and “Big Brother is watching you” becoming a looming fact of reality along with acceptance by a less educated population. Exactly what the socialist elements in the ANC are determined to achieve.