HOPE REVISITED OP-ED

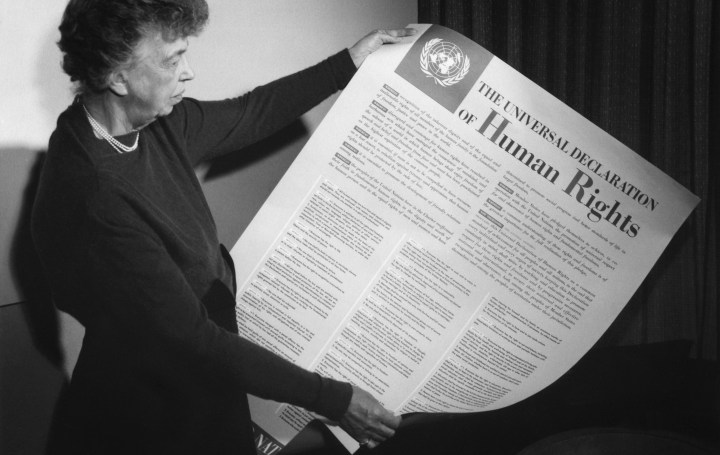

The voices and the visions behind the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Today is International Human Rights Day. At a time when human rights are being violated all over the world, often with impunity, it may help us to use this occasion and go back and capture what the states who negotiated the Universal Declaration of Human Rights thought about its political significance at the time of its creation. And to try to recover that spirit.

December 10, 1948 was a crystallising moment in world history. It was the day when the United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights just before midnight at the Palais de Chaillot near the Eiffel Tower in Paris. This was where the UN General Assembly was in session that year. It was a memorable occasion, as the UN delegates were well aware. It is an occasion that we celebrate or commemorate every year on International Human Rights Day.

For this year’s 75th anniversary there is plenty to reflect on regarding the current state of human rights. We may feel despair or strive to find evidence of hope. It is hard to avoid a feeling of crisis for human rights, or of foreboding. This is despite the fact that we can identify noticeable human rights achievements in recent times. However, they may not feel like enough. We are left wondering about the gap between what could and should be and what is.

An anniversary sharpens our attention to such sentiments.

Read in the Daily Maverick: Universal Declaration of Human Rights at 75 – time to move beyond the politics of a ‘bygone age’

It may therefore be relevant to use this occasion and go back and capture what the states who negotiated the universal declaration thought about its political significance at the time of its creation.

The early stages of the negotiations in 1947 and 1948 took place under the auspices of the UN Commission on Human Rights. It moved to the UN General Assembly from late September 1948. This meant engaging a much larger group than the core drafters as all the member states of the UN at the time were involved here. It was in this final stage – involving a total of 81 meetings – that the universal declaration found its final form.

Pakistan’s foreign minister, Mohammed Ikramullah explained succinctly his country’s position on the universal declaration during the General Assembly debate: “The aim of the declaration was to define the principles which should regulate a civilised society.” He thereby struck a theme that also African states would emphasise when they, during the following decade, began to enter the UN in greater numbers, namely that the UDHR reflected civilised society.

It is worth mentioning that at a later stage during the 1948 negotiations, Pakistan played a decisive role in ensuring that the “freedom to change religion or belief” would become part of Article 18 on the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion – an early UN decision that has had a long legacy.

The delegate from the Philippines declared on 7 December 1948, when the prospect of adoption was moving closer, that: “A bill of human rights had long been needed by mankind and was necessary for the foundation of a common world order.” From the Philippines’s perspective human rights were directly linked to what international order should consist of in the post-World War 2 era.

The Lebanese delegate, Karim Azkoul, echoed something similar, although in a way that struck much closer to home. He said that “Lebanon owes its existence to the concept of the rights of man. It is its faith in those principles that justifies its existence and should it lose that faith, it would be because it had no wish to exist.” Human rights were an existential matter for Lebanon’s ability to function as a state living in peace and stability.

Azkoul also spoke – already on 2 October 1948 – about the prospect of the UN voting for the universal declaration: “Through its adoption, the peoples of the world would be able to renew their badly shaken faith and belief in the value of man.”

It is worth noting that both the Philippines and Lebanon would go on to play instrumental roles in saving the human rights project at the UN when the US and the UK in 1951 proposed closing down the different UN human rights bodies, including the UN Commission on Human Rights. These nations were trying to smother the nascent human rights project inside the new international organisation.

In the political process that ensued, the Philippines and Lebanon were among a key group of Global South states that stood up against the two bigger powers, salvaged the project from its near-death experience and helped resuscitate it during the 1950s to document its value for the international community. Their 1948 positions on the universal declaration and what they represented proved to have a significant afterlife.

The delegate from Ecuador, Jorge Carrera Andrade – a diplomat, poet and historian – was equally clear when assessing the historical significance of the drafting work the UN was undertaking: “The international declaration of human rights was the most important document of the century,” he said later, adding that the declaration “must be a tool in the hands of the man in the street and not a mere ornament of international law”.

Charles Theodore Te Water (4 February 1887 to 6 June 1964) was a South African barrister, diplomat and politician who was appointed as President of the Assembly of the League of Nations. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Opposing viewpoints: South Africa

There were, of course, opposing viewpoints with a negative outlook. They came most prominently from South Africa and the new apartheid government who were determined to undermine the work on the declaration.

The South African ambassador, Charles Te Water, argued: “Men and women had and would always have different rights.” He continued that there could be “no universality in the concept of equality”, nor was there “any universal standard among the peoples of the world in their different concepts of human dignity”. This was despite that the international community was gathered exactly to define universal standards with a practical application such as a ban on torture.

The South African ambassador’s statement was only the early stages of what became a long conflictual relationship between the apartheid regime and the UN. A lot has been written about this. For now, it may suffice to quote the clear-sighted diagnosis by the French jurist René Cassin, who was one of the main drafters of the universal declaration and who had lost 26 family members in Auschwitz.

On 2 October 1948, Cassin stated: “The violation of human rights in a given country, as shown by the precedent of Hitler, could in fact be a preliminary to an attack upon the independence of other nations.” Without knowing it, he had – in one sentence – just summed up the 45-year history of apartheid South Africa that was about to unfold from the 1948 vantage point. Clearly, human rights can really help to sharpen your senses.

Including economic rights

One thing that is really striking from the historical sources is the common ground that existed regarding the relevance of including economic and social rights in the declaration. There was a broad consensus about this although specific understandings of these rights differed. The rights to health, education, work and the protection of motherhood and childhood were all among the rights debated here.

It was, however, two other issues that were particularly noteworthy in the debates.

The first was the debate about the historical lineage of economic and social rights. Mexico argued that they had a longer trajectory going back to the 18th century: “[Thomas] Jefferson stated in his declaration that man was always striving towards happiness and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen drawn up during the French Revolution contained the idea of equality in the economic and social fields.” Mexico continued this lineage up to their own constitution from 1917 and to ILOs Philadelphia Declaration from 1944.

The Cuban delegate Guy Pérez Cisneros – it is worth noting the prominence of the Latin American countries in this debate – offered a shorter version of the history of rights. He believed that the bringing together of civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights reflected that “the 20th century had witnessed the development of a new concept of liberty which it was important to clarify in the declaration”.

The two statements came to the substance with different perspectives but they both added up to a ringing endorsement of economic and social rights as human rights.

The Argentinian ambassador, Enrique V Corominas, bridged this debate over history with the second standout debate on social and economic rights, which focused on the specific right to social security. On 15 November 1948, he explained that “the Argentine delegation feels that the right to social security is a principle which should be clearly set forth, independently of the other economic and social rights. The idea of social security is now universal.”

Corominas continued:

“Social security is both a doctrine and the realisation of that doctrine in practice. Even before that idea had become as widespread as it was at present, it had been expressed in the form of human solidarity among the peoples of the world. The way in which social solidarity had been converted into social security constituted a triumph of the proletariat in the struggle against poverty. In the opinion of the Argentinian delegation it would be an unpardonable mistake if the right to social security were not guaranteed in the declaration of human rights. To guarantee it while making it dependent on other economic, social or cultural factors would be to diminish it.”

France argued essentially the same, thinking it “inconceivable that an international declaration of human rights drafted at the present moment in history should not contain a single mention” of the specific words “social security”. It was this determination that resonated throughout the debate. History, political storytelling and international human rights diplomacy were coming together in ways that would produce a powerful political outcome.

Belgium added a further perspective to this debate when they argued that it was necessary to add the words “social justice” to give a fuller meaning to what the right to social security meant.

From cradle to the grave

At the same time, a clear transnational inspiration was reflected in proposals for concrete wording by states.

Panama borrowed a British welfare state framing (“from the cradle to the grave”) – which had appeared with Lord Beveridge’s legendary wartime government report, “Social Insurance and Allied Services”, in late 1942 – when they submitted the following article for consideration:

“Everyone, as a member of society, has the right to social security from the cradle to the grave and is entitled to the realisation, through national effort and international cooperation, and in accordance with the organisation and resources of each state, of the economic, social and cultural rights set out below.”

The “from the cradle to the grave” language was not adopted as part of the right to social security, but it is further indication of the richness of the debate that unfolded.

The larger social vision at play – what I would call a social internationalism – that guided the work on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was eloquently summed up by the Brazilian delegate Austregésilo de Athayde. He considered “the rights of the individual to material well-being as one of the most important articles in the declaration”.

“Food, clothing, housing and medical care are vital necessities not only for the individual but for society and for the State. Neither society nor the State can continue to exist unless the individual enjoys the minimum standard of living which that article aims to guarantee. Protection of the family, security in case of unemployment, sickness, disability, old age, etc are rights that are important to society as a whole.”

We could easily express the same sentiment today. That might actually be one of the lessons we can distil from this journey back to the UN in 1948.

It is not just a walk down Memory Lane. It should also be a walk along Contemporary Lane and Future Lane because the rights visions expressed by these historical actors make the universal declaration feel so relevant today.

The point may be – in this domain at least – that they are our contemporaries and that the 75-year-old declaration – no matter our own age – is and will remain our contemporary. It is perhaps time we embrace the birthday kid once again. DM

Steven LB Jensen is a prize-winning human rights historian. He is the author of The Making of International Human Rights. The 1960s, Decolonization and the Reconstruction of Global Values (Cambridge UP 2016) and editor of Social Rights and the Politics of Obligation in History (Cambridge UP 2022). He holds a PhD in history and is a senior researcher at the Danish Institute for Human Rights. He is a regular contributor to Open Global Rights. He is currently working on a history of social and economic human rights in 20th-century international politics.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Since the decleration has the world become a better and safer place???