THE NEW MESSIAHS

Why are so many brilliant Big Tech pioneers such arseholes?

With the data now in, it is clear that the advent of social media has created a social, cultural and political disaster around the world in the past decade and a half. How did the visionaries of Big Tech allow this to happen, and what does this mean for the coming age of artificial intelligence?

Recent weeks have seen extraordinary scenes in Silicon Valley. A failed palace coup at OpenAI, the world-leading artificial intelligence research company now valued at close to $90-billion, resulted in its CEO, Sam Altman, being fired and then rehired within days. The board members who had become concerned by his leadership were, in turn, shown the door.

As the drama unfolded, parallels with the ousting of Steve Jobs from Apple in 1985 were all too obvious and, as it resolved in Altman’s favour, it saw the 38-year-old become firmly entrenched as the new Jobs of our time.

To some this is an aspirational achievement. Jobs was a visionary, a tech industry revolutionary whose messianic reputation still stands today, 12 years after his death. To others this is deeply concerning. Jobs was notoriously difficult to work with, and after his return to Apple in 1997, he effectively controlled his board, as many prominent tech CEOs seem to do these days. Should the development of AI be controlled by inordinately powerful individuals?

Since the release of ChatGPT in November 2022, Altman has become the face of the new age of AI. He has addressed US Congress, met with world leaders, including Joe Biden and Rishi Sunak, and assumed Jobs’s mantle as the one guy that Silicon Valley acolytes are most desperate to see on stage presenting new products. Microsoft, now a 49% shareholder in his company, has sent $13-billion in his direction.

By all accounts, Altman’s turn at OpenAI DevDay on 6 November, the company’s first development conference, was a triumph – so much so, insiders have suggested, that it was the tipping point when the board realised he needed to be reined in.

One of the critical points of contention in the field of AI right now is getting the balance right between developing the technology as quickly as possible and as safely as possible. Altman is considered an “accelerationist”, whereas the board appeared to be guided by “decelerationist” concerns.

OpenAl chief executive Sam Altman speaks during the OpenAl DevDay event on 6 November in San Francisco, California, shortly before his axing from and quick reinstatement to the board. (Photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

In retrospect, the board didn’t stand a chance: upon Altman’s dismissal as CEO, Microsoft gave him its immediate and unequivocal public backing, and more than 95% of OpenAI’s 750 staff signed a petition calling for his reinstatement. The upshot is that Altman remains in charge of the company at the forefront of AI development, a technology that seems likely to revolutionise the world in the coming years, perhaps even more so than PCs, the internet and smartphones have done before – and with some particularly ominous potential downsides.

As industry writer Johana Bhuiyan notes: “The development of cutting-edge AI rests in the hands of a small, secretive cadre that operates behind closed doors.”

As important as this flourishing technology promises to be, it is near impossible to predict how things might play out.

But what might this power tussle reveal about the future of AI and its coming implementation across society? There are various perspectives from which to try to answer this question. One is historical, and begins with a related question: Why are so many prominent Big Tech founders and industry leaders such profound arseholes?

The archetypal bad boss

Tales of the seemingly inhuman behaviour of Jobs, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg and company are legion. Arrogant, antisocial, selfish, one-eyed, impossible. What is it about the dynamics of the tech industry that celebrates this way of being and translates it into world-changing business success?

In his 2022 book The Chaos Machine, Max Fisher offers an explanation with his description of the Silicon Valley pioneer William Shockley. In the 1940s and 1950s, Shockley played a role in the invention of the modern transistor, for which he, along with two collaborators at Bell Labs in New Jersey, would win the Nobel Prize in Physics. He then quit Bell to start the Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory, relocating from the East Coast to Palo Alto, San Francisco.

Shockley’s business was the first to work on silicon devices in the area, and so Shockley became “the man who brought silicon to Silicon Valley”. He soon attracted an array of brilliant young minds, many of them seemingly awkward outsiders who, like their new boss, didn’t fit into the establishment on the East Coast. He attracted them and then he repelled them.

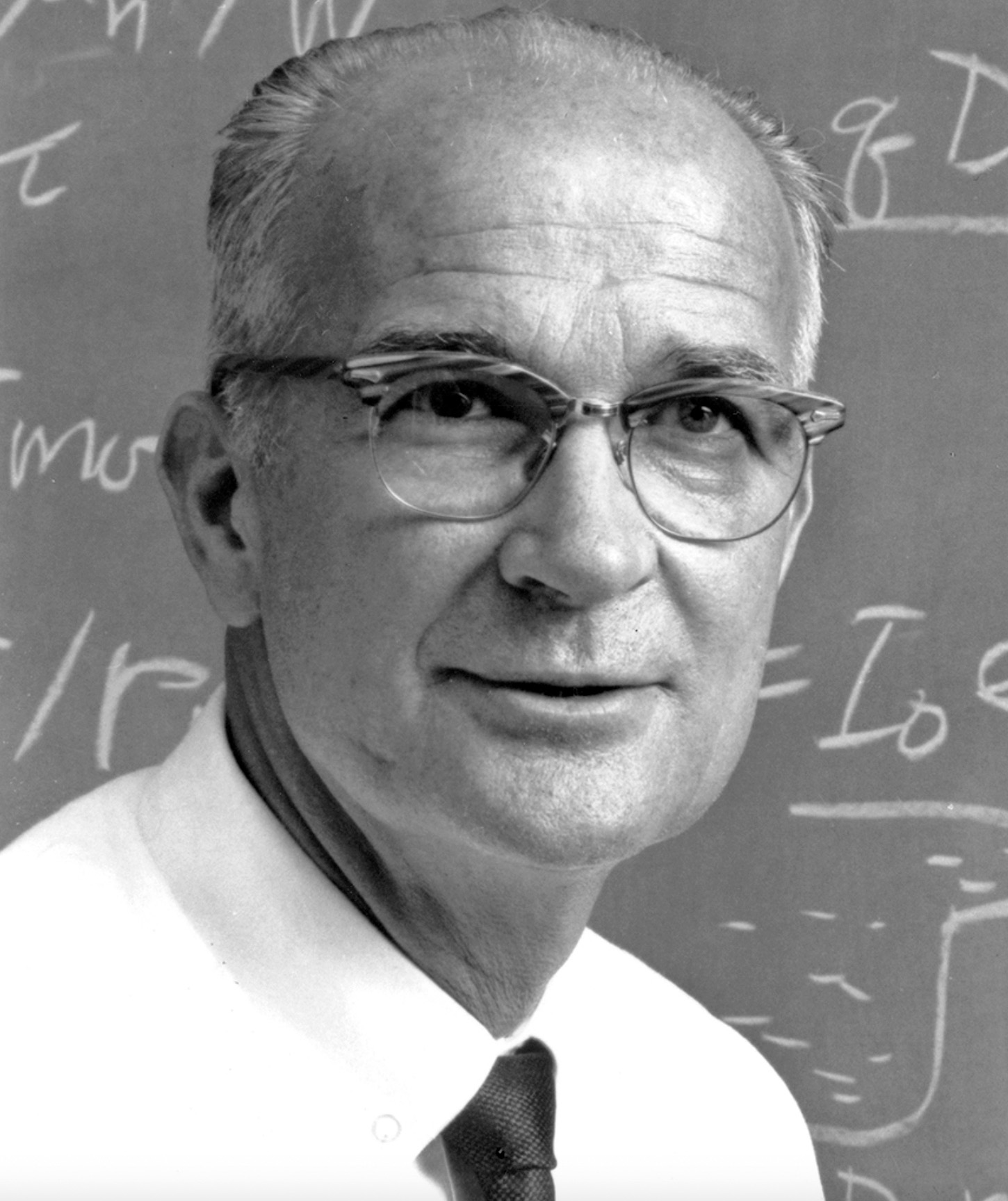

Shockley was the tech industry’s archetypal bad boss. Mean, manipulative and ethically challenged, he “may have been the worst manager in the history of electronics”, according to his biographer, Joel Shurkin. Remarkably quickly, he ruined his relationships with all his protégés, including a clutch of geniuses who quit and went off to start Fairchild Semiconductor. Fairchild would go on to become one of the most influential companies in Silicon Valley.

By all accounts, Shockley was brilliant but reprehensible, alienating not only his colleagues but also his children, who would eventually read of his death in the newspaper obituaries. He died in disgrace, having become a prominent advocate of eugenics in later life, with visions of a future world filled with people just like him.

Such was Shockley’s esteem as an inventor and physicist, however, and so prominent was his role in positioning San Francisco at the centre of the tech revolution that he became an icon for many of the aspirational CEOs that it came to produce. Not for nothing is he often referred to as “the founding father of Silicon Valley”. As Fisher puts it, Shockley’s formative company “established Valley start-ups, forever after, as the domain of self-starter misfits rising on raw merit – a legacy that would lead its future generations to elevate misanthropic dropouts and to excuse toxic, Shockley-style corporate cultures as somehow essential to the model”.

Willian Shockley in 1975. He died in disgrace, having become a prominent advocate of eugenics in later life. (Photo: Chek Painter/Stanford News Service)

Role of venture capitalists

Reinforcing this operating model was the new financial model that would come to dominate the growing tech industry. With Wall Street money tending to steer clear, discouraged by long distance and the technicalities of tech, the first tranche of successful Silicon Valley entrepreneurs developed what came to be known as venture capitalism.

“And,” writes Fisher, “venture capitalists tended to fund people whom they trusted – which meant people they knew personally or who looked and talked like them. This meant that each class of successful engineers reified their strengths, as well as their biases and blind spots, in the next, like an isolated species whose traits become more pronounced with each subsequent generation.”

Thus, Shockley takes the blame for effectively normalising the CEO-as-deplorable-wizard-nerd trope, and we have a better understanding of how Jobs could be hailed as a contemporary messiah despite seeing fit to let his daughter and her mother live off welfare, among a long list of examples of egregious behaviour.

And how Gates could build his fortune around a company-killing monopoly (while refusing to take a holiday for over a decade), and then have the chutzpah to reposition himself as the saviour of humanity.

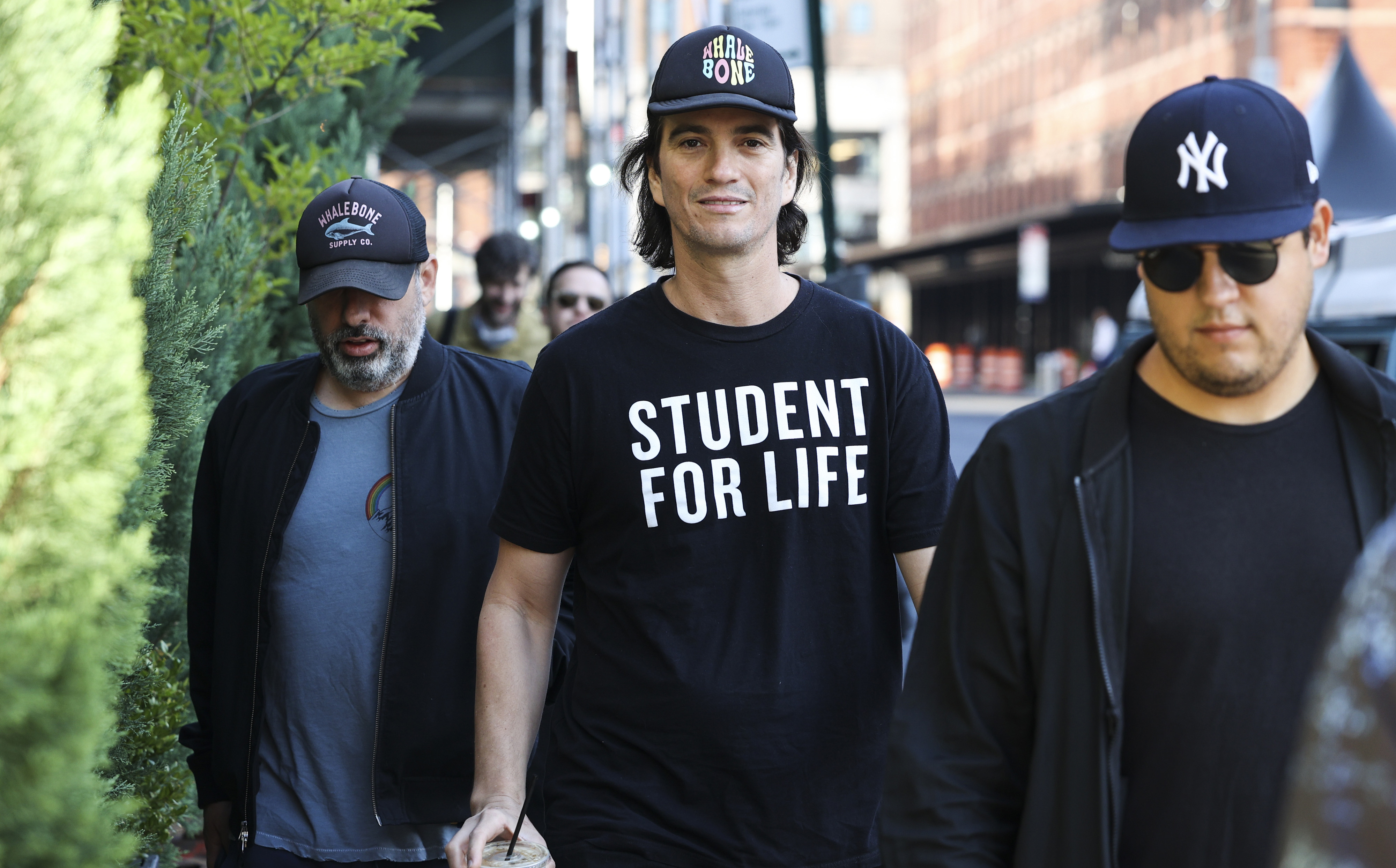

And how outrageously any number of Big Tech CEOs have abused and alienated their staff (Uber’s Travis Kalanick), defrauded investors (Theranos’s Elizabeth Holmes) or declared their ambitions to be “president of the world” (WeWork’s Adam Neumann).

As long as the Nasdaq is soaring, they can do pretty much what they want.

Adam Neumann, the founder of the now bankrupt WeWork, is among the Big Tech CEOs who have behaved outrageously. (Photo: Angus Mordant/ Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Social media and dubious ethics

With that, we come to those who have been at the forefront of the social media and surveillance capitalism revolution of the past two decades: the powers that be at Facebook (now Meta); Twitter; Google and YouTube (both now under Alphabet); and the like.

Many are leaders with notoriously bad interpersonal skills, who have been guiding an unprecedented global experiment in human interaction. The antisocial kings of social media.

Zuckerberg is the definitive individual here, a man whom the prominent industry commentator Scott Galloway has described as a “sociopath” on numerous occasions. In 2007, when Facebook was taking off, Zuckerberg shared this insight: “I want to stress the importance of being young and technical. Young people are just smarter.” Even if taken somewhat out of context, this quote hasn’t aged well.

Yes, young people have more agile minds and are likely to be better mathematicians, for example, but they are less wise, more idealistic, less emotionally developed and take more risks. As most older people would be able to recognise, being “smarter” is a multidimensional affair.

Having formulated TheFacebook.com under dubious ethical conditions, Zuckerberg evolved his transformative social media platform under the mantra “move fast and break things”. In time, he and his social media cohorts broke the very fabric of society.

For a long time, this conclusion – that social media was a net disaster for the modern world – was not even countenanced. How could connecting people not be an unalloyed good? This was the steamroller attitude that paved the way for radical political polarisation and a pandemic of mental health problems. For years the mounting evidence was simply ignored.

For those readers still not convinced by just how destructive social media has been and continues to be, I recommend two recent books: The Chaos Machine and Stolen Focus by Johann Hari.

Hari investigates the damage to individuals: how we’ve had our concentration hijacked and become addicted to the online dopamine-hit cycle at the expense of our collective mental health. Much of what he writes about isn’t in fact new, but his case is comprehensive and (now) inarguable.

Social media is, in effect, a continuing experiment on human populations, the digital equivalent of releasing a highly addictive new drug around the world without trialling or regulating it.

At one point Hari interviews Aza Raskin, the inventor of “infinite scrolling”. “Every day, as a direct result of his invention,” he writes, “the combined total of 200,000 more human lifetimes – every moment from birth to death – is now spent scrolling through a screen.” Raskin deeply regrets his invention.

In revealing some of the extreme techniques he uses to overcome digital distractions – for instance, regular use of time-lock boxes and apps for his devices – Hari compares it to trying to diet in a modern world of unhealthy options. The system, designed by the smartest (or perhaps “smartest”) engineers in the world, with unfathomable amounts of money behind them, is decidedly against you. It is only the rare individual who can avoid all the pitfalls and remain healthy, which is to say probably not you, and certainly not your teenage kid.

Meanwhile, Fisher unpacks the disaster of social media at group level, which reveals it to be an existential threat to liberal democracy and even peace. Among other examples, he dissects YouTube’s laser-focused goal of reaching a billion hours of watch time per day in 2016, with continuing revisions of an algorithm that no one at the company – or in the world – really understood. Users often didn’t actually like what they were compulsively watching; they were “machine-manipulated” into doing so.

The effects, however, were there for all to see. Someone looking for ordinary medical advice, for instance, might find themselves viewing anti-vaxxer videos a few clicks later and then 4chan conspiracy videos a few clicks after that. The cult of QAnon followed in 2017. Thus YouTube begets 4chan, which begets QAnon, which begets the Capitol Building riots in January 2021, one of the gravest threats to US democracy in living memory.

Elizabeth Holmes, the founder of the now-defunct blood-testing start-up Theranos who is serving 11 years in prison after being convicted on four counts of fraud. (Photo: Lisa Lake/Getty Images)

Surprise! It’s harmful

A common theme that resurfaces regularly in Fisher’s book is Big Tech’s inability to look within. In one case, an influential industry personality confesses to having been an instigator of online harassment and shaming campaigns, only to realise how damaging they are – and how toxic social media is – when she becomes the target of one herself. This is a revelation to her.

Fisher is most damning of Facebook. In light of the company’s plan to monopolise social media in foreign markets in languages it didn’t monitor with actual humans – just letting the algorithms run the show – he describes how there was “no need to monitor or even consider the consequences, because they could only be positive”. The result: lynchings in Mexico, ethnic mob violence in Sri Lanka, genocide in Myanmar.

His in-depth interviewing of senior executives at Facebook and elsewhere leads to a bleak conclusion: “Some combination of ideology, greed and the technological opacity of complex machine-learning blinds executives from seeing their creations in their entirety. The machines are, in the ways that matter, essentially ungoverned.”

The world has been desperate for meaningful regulation of social media for years – at least since the mid-2010s when US elections were undeniably influenced by it. In 2015, prominent social psychologists such as Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff first sounded the warning of extreme declines in teenage mental wellbeing.

But legislative progress has been negligible, especially in the US where it matters most, and where putting the brakes on the tech companies helping to drive the economy is a political non-starter.

Instead, the companies have “self-regulated” according to shareholder priorities. Superficial tweaks have papered over whatever public pushback there may have been, and damning data has simply been ignored as a generation of children was thrown under the bus.

Twitter, a platform that has driven so much political polarisation around the world, didn’t even bother appointing a full-time CEO from 2015 to 2021. (A good starting point if you ever wonder how Elon Musk came to be in charge of what is now X.)

Facebook actively suppressed its own findings that it was amplifying public harm, chose not to make the changes that would stop this harm and lied about it repeatedly and publicly. And, all the while, any regulatory fines these companies have received are priced in.

Among a raft of other sensible recommendations, there is a single obvious fix that would go a long way to halting and ultimately reversing the continuing social media meltdown. The legislation of a change from an advertising-driven to paid-for business model would largely negate the industry’s priority of gaining and holding user attention, and all the negative social consequences that result from this approach.

Instead, the focus would have to be on quality content that people are willing to pay for. And, whether it’s through decades-late regulation or simply market forces, as the dangers of social media become more widely publicised – just as those of Big Tobacco were in the past – this seems to be a likely resolution in the longer term.

The biggest threat yet

Composite image of, from left, Geoffrey Hinton, who is regarded as the ‘godfather’ of artificial intelligence, and Elon Musk, chief executive of Tesla, owner of X and cofounder of OpenAl. (Photos: Cole Burston and Nathan Laine – both Bloomberg via Getty Images)

The social media problem is, however, being superseded by an even greater threat to society. The past year has seen the widespread introduction of remarkable AI chatbots developed from large language models, most prominently OpenAI’s ChatGPT.

Although there is much optimism for what AI might achieve – massive advances in human healthcare, for instance – the downsides are potentially catastrophic and widely being reported across global media.

In March 2023 a prominent group of tech industry personalities, including Musk and Steve Wozniak, called for a six-month halt on AI development to get regulatory guidelines in place. The “godfather of AI”, Geoffrey Hinton, left his position at Google specifically to publicise his concerns, calling AI “a bigger threat than climate change”. In May, Sam Altman testified before the US Congress that “regulation of AI is essential”.

The concern that a self-conscious entity emerges and puts us in the Matrix (of The Matrix) is still some way down the line. More pressing now is the potential for the mass disintegration of human employment; disinformation campaigns exponentially worse and more effective than anything dreamt up on social media; and the weaponisation of AI in a way that makes it comparable to the threat of nuclear weapons.

The question is, then, with Big Tech’s dire track record in people-oriented leadership and self-regulation to date, and the interminable inability of governments to offer practical oversight, how is AI going to be managed in the years ahead?

Some positive aspects

One positive aspect this time around is that the dangers of AI – both known and unknown – are being sung from the rooftops. Social media may have been birthed with a blank utopian slate, but The Terminator was released in 1984.

The CEOs and decision-makers of the companies at the forefront of AI technology right now – the leaders at OpenAI, Microsoft, Alphabet and beyond – won’t be able to claim they weren’t warned at the start. This is why the tension between the accelerationists and decelerationists exists.

A second positive is that those leaders today are not 20-something college undergrads, building their start-ups in between class, overwhelmed by idealism, thinking they’re smarter than everyone else. But many of them were. Have they matured and stepped out of the shadow of Shockley?

In public, Altman appears to be fresh-faced and humble, always praising the team he “loves”. But how does a young man retain his sense of perspective as the funding billions keep raining down?

Following his failed ousting, he will only be more aware of the power he wields as an individual. In an industry niche that is self-regulated, just as social media was for so many years, this does not necessarily bode well.

As Paul Barrett, the deputy director at the NYU Stern Centre for Business and Human Rights, puts it: “Huge amounts of money – and huge egos – are in play. Judgements about when unpredictable AI systems are safe to be released to the public should not be governed by these factors.”

Since the 1980s, the leaders of Big Tech have been put on pedestals and praised as modern gods, but have they worked out yet what it’s like to be a normal everyday human? And, even if they have, will they be able to keep the machines in check? DM

Tim Richman is a publisher at Burnet Media.

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper, which is available countrywide for R29.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

this is an anti-facebook rant with almost no tie to its title. there is no discussion about CEOs in other industries. Only two individuals are described to be arseholes. Many of the other examples given are decidedly non-arsehole (imagine nearly the entire staff of a company threatening to leave once the CEO is fired; that speaks of a man who is loved and supported).

Well written and to the point. The same arrogance and with the ” young know it alls” have feasted off the Crypto ponzi schemes.. now that’s a sack full of arseholes

Can be described in a single word – “hubris”

It doesn’t seem to have occurred to anyone writing about them that these tech giants are to a high degree of certainty ASD Level 1 individuals (formerly “Asperger’s syndrome,” colloquially known as “Aspies”). This would explain both their singular, even obsessive, focus, perseverance, and intellect that ensured their success, and also their difficulties when dealing with neurotypical people, in particular being perceived as abrasive, difficult, antisocial, self-centred, and all of the other negative attributes mentioned in the above article.

There is widespread societal bigotry against Aspies mainly due to a pervasive ignorance about what bedevils them, added to very common disdain for people with mental / personality disorders. It is extremely naïve and egregiously ill-informed to contend that Aspies can (and should or even must) consistently suppress their true natures. You may as well blame a muscular dystrophy patient for not being able to dance.