21 MARCH 1960 REVISITED

What really happened in Sharpeville — new book reveals many more died in the massacre

A new book turns the official narrative about the 21 March 1960 massacre on its head. The crowd that gathered on that fateful day was actually peaceful and did not pose a threat to anyone’s life.

Extensive new research, including thorough reviews of medical records and police documents, drastically increases the number of dead and injured in the Sharpeville Massacre by at least a third.

This is published in a new book, Voices of Sharpeville: The Long History of Racial Injustice, which was released internationally this week. It will be launched locally in February 2024 at an event in Sharpeville.

Using various sources, it is shown that at least 91 people (and likely more) were killed on 21 March 1960 and at least 238 injured, many of them very severely. The official police report was of 69 dead and 186 wounded.

Two emeritus professors of history, Nancy Clark of Louisiana State University and William Worger of the University of California, Los Angeles, compiled a set of eyewitness testimonies from Sharpeville’s residents.

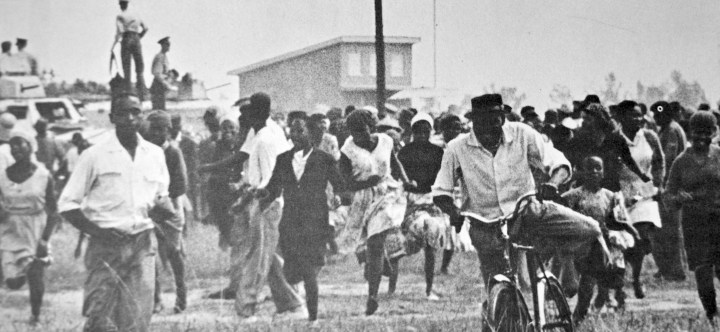

Previously understood through the iconic photos of fleeing protesters and dead bodies, the timeline is reconstructed using an extensive archive of new documentary and oral sources, including unused police records, personal interviews with survivors and their families, maps and family photos.

By identifying nearly all the victims, many omitted from earlier accounts, the authors upend the official narrative of the massacre.

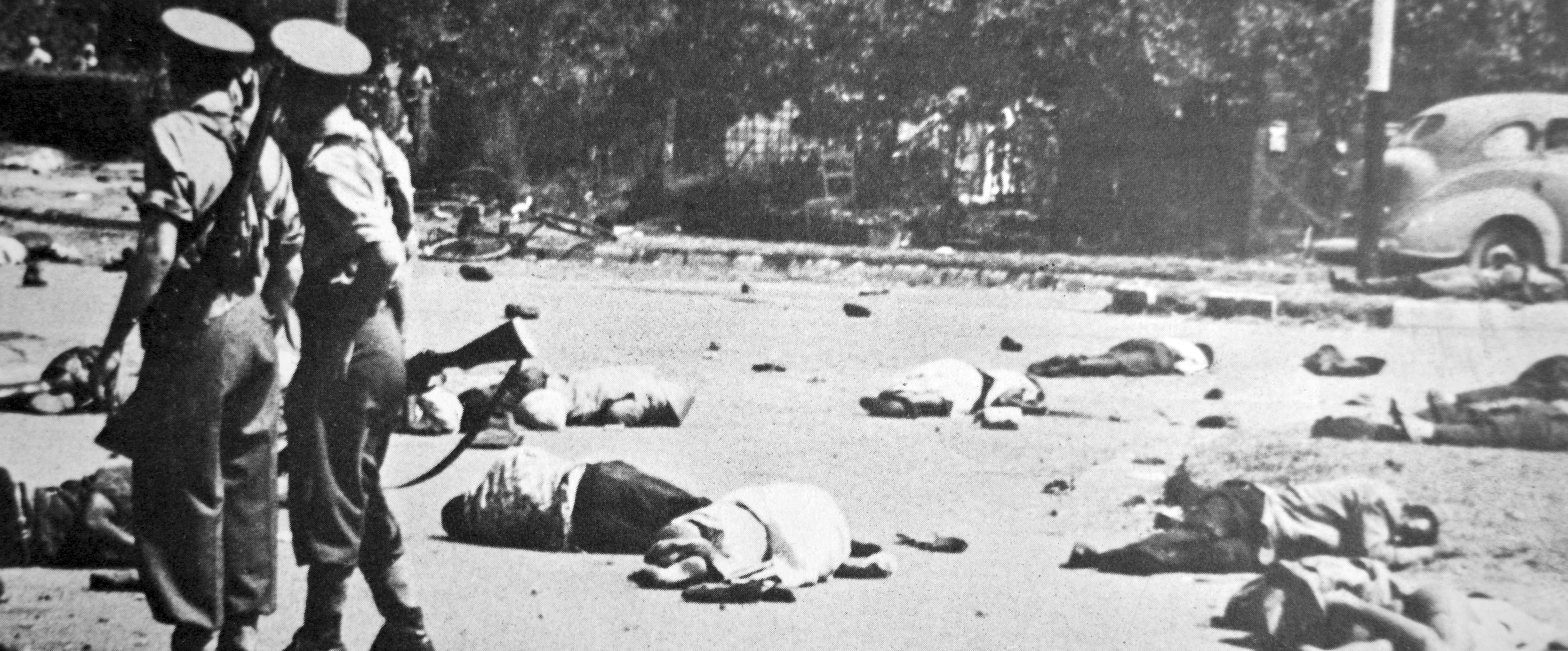

Members of the police are surrounded by the bodies of victims of the Sharpeville Massacre. At the time, the apartheid government instituted an official inquiry into the events of the day and the death toll was put at 69. That number is now in dispute after new research. (Photo: Universal History Archive / UIG via Getty images)

Change of focus

“I was initially interested in the location and design of Sharpeville, one of the few African townships planned and constructed during World War 2, as an example of pre-apartheid urban planning,” says Clark.

Research for the project continued intermittently. However, as more records became available after 1994, the focus of the project turned to the massacre.

Their research intensified when they were able to contact survivors five years ago.

“Our contact with the people of Sharpeville came through work that we were doing with Freedom Park, which was digitising interviews with many struggle activists,” says Clark. “We were invited to accompany the Freedom Park interviewers to Sharpeville in 2018 and that is when we made personal contact with Sharpeville survivors and activists.”

The book gives a minute-by-minute account of that fateful day and its aftermath, which Clark and Worger have managed to weave into a rich tapestry of facts and deeply personal experiences.

Nearly all the victims, killed and injured alike, were shot in the back. As the police aimed their guns at the crowd, most people turned and ran even before the shooting started.

In 2017, they obtained a microfilm copy of the 1960 report of the official inquiry into the massacre. They discovered that the microfilm – available since the early 1960s – also contained the transcripts of a trial of more than 20 Sharpeville residents for their actions on 21 March.

“In combing through the transcripts, it became obvious that the story of these residents as well as the police involved was quite different from the reported accounts by the government and that, by all accounts, the crowd was peaceful and the shooting was intentional.

The Sharpeville Exhibition Centre, also known as the Sharpeville Human Rights Precinct, on 14 January 2021. It is one of six memorial sites dedicated to the massacre and its role in the eventual downfall of apartheid. (Photo: Fani Mahuntsi / Gallo Images)

“In turn, these discoveries led to a search of the South African National Archives in 2018 that uncovered a trove of police files, including over 300 additional compensation claims made by South African citizens – wounded and families of the dead – in 1960 and 1961, as well as the official autopsy and medical reports of many of the victims.

“Nearly all the victims, killed and injured alike, were shot in the back. As soon as the police aimed their guns at the crowd, most people turned and ran even before the shooting started.

“Owing to severe restrictions on the police files as well as any in the ‘Native Affairs’ collections during the apartheid era, these materials had never been accessible prior to 1994,” explains Clark. “The staff at the National Archives in Pretoria helped us locate these materials as they had not been properly catalogued under the pre-1994 administration.”

Because there was such secrecy and silence around the massacre, there were many misconceptions about Sharpeville and the events on 21 March.

Important historical corrections

First, the community of Sharpeville at that time was made up of long-time residents who had moved from Vereeniging’s previous “location”, Topville.

They were employed at factories and businesses in Vereeniging and were not recent migrants or unemployed jobseekers. The community was stable and industrious.

Second, rather than an angry and threatening mob, the residents assembled at the police station in an orderly and peaceful manner. According to testimony from residents and journalists, and even the location superintendent, the crowd was relaxed and friendly, and they were waiting to be addressed by senior government officials when the shooting started.

The police action was highly coordinated, and overwhelming force was brought to the township.

In photographs, anyone can see that the residents were dressed in their best clothes and not in the work overalls and uniforms worn by women as domestic workers.

“They did not appear to be ready for a fight,” said Clark. “As their leader, Nyakane Tsolo, later said: ‘We never thought they would kill us…’”

Third, the police action was highly coordinated, and overwhelming force was brought to the township. This was not the action of flustered or inexperienced officers and, according to the testimony of some officers who had been present, the shooting was ordered by the officer in charge.

“The massacre has always been shrouded in some mystery and the records buried away. But we found that there are in fact many survivors who have been eager to tell their stories, certainly since 1994, but found there was little interest,” says Clark.

“Superseding events in the 1970s and 1980s that may have overshadowed Sharpeville, or a belief that the truth was ‘unknowable’ have prevailed as reasons for a lack of interest in the 21 March 1960 massacre, but there is always evidence of the truth.”

The Sharpeville Memorial and Exhibition Centre on 13 January 2021. It is on Seeiso Street, opposite the police station where the massacre took place. (Photo: Fani Mahuntsi / Gallo Images)

Last, this tragedy could have been avoided. There were similar gatherings in nearby Bophelong, Boipatong and Evaton, and also in Langa, Cape Town, later the same day, but they did not result in similar massacres.

“Sharpeville was hardly known as a hotbed of political activity at the time, certainly less active than some other areas. The people of Sharpeville were waiting to hear an address by senior government officials in response to their objections to the pass laws, or alternatively, to be arrested as Robert Sobukwe and other PAC leaders were in Orlando. The only violence that was threatened was on the side of the police, who were heavily armed with Sten guns and Saracens.”

The authors write in the book that there was only one officer-in-command (OIC) at the time of the massacre and that was Lieutenant-Colonel Gideon Daniel Pienaar.

“Though he, and the police, and the government will always deny it, the evidence given under oath by African and white witnesses alike is overwhelming that at 1:40pm on 21 March 1960 the OIC at Sharpeville, Lieutenant-Colonel Pienaar, orders 77 white policemen armed with machine guns, rifles and revolvers to fire directly into an unarmed and peaceful crowd.”

Read more in Daily Maverick: Old apartheid police station a place of hope amid grim daily life in Sharpeville

According to their telling, almost 1,400 bullets were fired in 45 seconds by every single policeman in the line – except one, a certain Constable Simon Andrew van den Bergh. More than half of these bullets came from the Sten submachine guns.

“It is ‘a firing squad’, it is, said Captain [Frederick Jakobus Pieter] Coetzee, looking out at the crowd behind the fence, like shooting ‘fish in a tin’.”

“It rained after the shooting, said Maria Makhoba. ‘The streets have been washed clean of blood by a thundershower. Pools of water have collected where only a few hours ago there was blood.’ She waited at home for her 14-year-old son to return home, but he never did.” DM

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper, which is available countrywide for R29.

Page 1. Front page DM168. 18 November 2023

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

My dear departed Mother was what we would call these days an”anti apartheid Activist”, and a founding member of the black sash.

In a book case facing the front door was a banned book “The shooting at Sharpeville” by Ambrose Reeves, the Anglican Bishop of Johannesburg – Who was exiled for daring to challenge the Official much manipulated story that was given out to try and cover up a tragic slaughter where almost all victims were shot in the back while fleeing away.

I have no idea where the book can be obtained these days

“The Shooting at Sharpeville: The Agony of South Africa” is a book written by Ambrose Reeves during his time as Bishop of the Diocese of Johannesburg1. The book provides a detailed account of the Sharpeville massacre that occurred on March 21, 19601.

Ambrose Reeves was an active and outspoken figure in the struggle against Apartheid. He was deported by the South African Government not long after the Sharpeville massacre, and he resigned as Bishop of Johannesburg in 19611.

The book was banned on February 24, 1961, and was included in the “Jacobsens” Index of Objectionable Literature under its titles “Bloedbad in Sharpeville” and “Shooting at Sharpeville”. It was unbanned on January 9, 1987.

If you’re interested in reading the full text, it appears to be available online:

archive dot org slash stream slash shootingatsharpe002466mbp slash shootingatsharpe002466mbp underscore djvu dot txt.