HUMANS OF SOUTH AFRICA

An ordinary life in turbulent times: memories of Rosemary Hough

Robert Morrell reflects on the life of Rosemary Hough, who died on 8 October 2023, and the history of South Africa she lived through. He touches on her friendships, and her ability to reach out across social divisions.

These are the days of miracle and wonder

This is the long distance call

The way the camera follows us in slo-mo

The way we look to us all

It was a dry wind and it swept across the desert

And it curled into the circle of birth

And the dead sand falling on the children

The mothers and the fathers and the automatic earth

These are words from Paul Simon’s The Boy in the Bubble, which he composed in 1986 along with Forere Motloheloa, and performed on his Graceland album with Ladysmith Black Mambazo.

They came to mind as I was reflecting on the life and death of my mother-in-law, Rosemary Irma Hough (nee Giffen). Rosemary was born on 5 April 1937 and died on 8 October 2023. The day before she died, while she was in ICU at Vincent Pallotti hospital in Cape Town, Hamas launched a surprise attack from the Gaza Strip, killing 1,400 Israelis. Since then, the world has been on tenterhooks while Israel’s military has bombarded Gaza, killing thousands and thousands of civilians.

Political divisions have widened and enmity has grown.

Rosemary’s life and our present times have made me think about many things including our country, South Africa. And this brings up these words “miracle and wonder”. In the wake of the amazing South African victory over the All Blacks to win the Rugby World Cup for the fourth time, it is hard not to think that these words are right. South Africa is a land of miracles and wonder. It is a land of heroes, and for now let me just name Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela.

Read more in Daily Maverick: The non-racial spirit of Nelson Mandela lives on in our victorious Springbok team

Miracles may seem magical but there is a social reality to them. How did South Africa enter the 1990s with hope rather than despair? There are many answers, but I want to single out one.

There are an infinite number of acts of generosity and kindness every day that bind people, that create possibility, overcome differences, that defy the odds of conflict, violence and hatred. The social historians of the UK developed an approach in the sixties and seventies to try and capture what orthodox “great man history” missed, the lives of ordinary people. EP Thompson explained the purpose of this approach – to retrieve people from the past and rescue them from the “enormous condescension of posterity”.

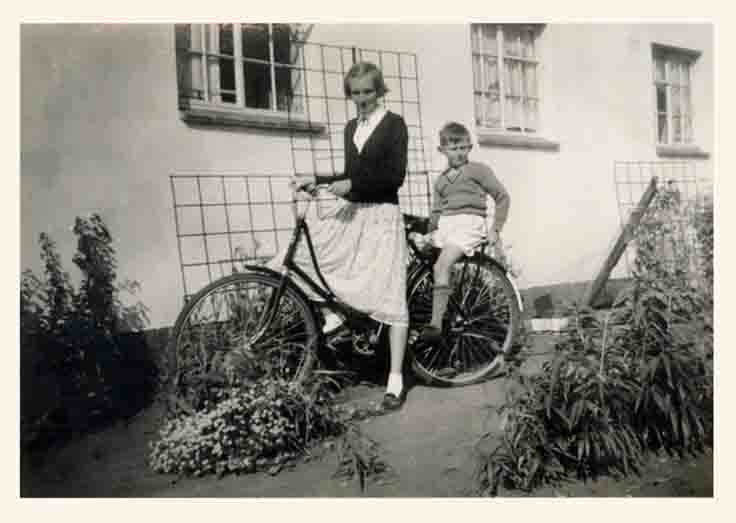

Rosemary and her brother, Robert. (Photo: supplied)

Extraordinary makings of an ordinary person

It is from this angle that I want to approach the life of Rosemary Hough – an ordinary life in a time of turbulence.

Born in 1937 in Johannesburg, she remembered World War 2 and the advent of apartheid with the election victory of the National Party in 1948. She was not surprised when apartheid was declared a violation of Human Rights by the United Nations in 1976, the year of the Soweto student uprising.

Rosemary, like many South Africans, was made up of many parts, and many of the currents that have shaped our lives flowed through hers.

Her parents were Roland Giffen and Irma O’Keefe. Roland was the third of seven children, born in Estcourt, Natal. His father was a railway engine driver. The family was short of money so he left school at the end of Standard 7 and found work on the railways.

Rosemary’s mother, Irma O’Keefe, was born outside Dublin and emigrated with her family at a young age and grew up in Pietermaritzburg. She was clever and, slightly unusual for the time, finished school and attended university at age 16, training to become a school teacher.

When she married Roland, she was forced to resign her teacher position – women teachers weren’t allowed to get married in those days …

Rosemary’s father, Roland, steadily rose in the ranks of the railways. He served in World War 2 (North Africa, Palestine and Italy) and reached the rank of major. The advent of the apartheid government meant that any future prospects were blocked. English-speakers gave way to Afrikaans-speakers. Roland’s way out was to accept a transfer to Lourenço Marques (now Maputo) in 1951, where he was responsible for railways and harbour operations.

Rosemary was a lifelong Catholic and attended Convent in Pietermaritzburg as a boarder, largely because her mother’s sisters lived in the city and became surrogate mothers. On completing school she did a BA (Law) at Rhodes University and then a postgraduate diploma in librarianship at UCT.

A life in libraries

In her time, she worked in the Library of the Appeal Court in Bloemfontein. “My boss was the registrar and the brother-in-law of Verwoerd. His first words to me were “Jy’s in die Vrystaat. Praat Afrikaans”. But more influential for her was Justice Oliver Schreiner who she greatly admired, and who did not insist that she speak Afrikaans – which was fortunate because Rosemary’s command of die taal was not good.

In her time she worked at libraries in Johannesburg (Johannesburg Public Library) and then for a time at UCT library.

In 1962, Rosemary married Koos Hough. Koos was born in Stellenbosch in 1937. His grandfather has been a policeman (and served in the 1922 Rand Rebellion) and his father had worked in the Post Office, leaving school in Standard seven because of the family’s poor circumstances.

Koos’s mother (Rita Botha) was born in the Transkei. She became a nurse aide. Her own mother had died in childbirth and when she in turn gave birth to Koos, she fell into a serious postpartum depression that left her with lifelong mental illness, including a spell in Valkenberg hospital. Koos was thus an only child and had periods with foster parents.

He was sent to Grey College, Bloemfontein, as a boarder to deal with his home conditions. There he became heeltemaal tweetalig and excelled at mathematics. He went on to have a career as a physicist, working at Stellenbosch University and the CSIR. He did not, however, escape the legacy of his mother’s mental illness and battled with depression his entire life.

Tides of change

By the time Rosemary died, South Africa and the world had changed a great deal.

South Africa had gone from being headed by Jan Smuts’s United Party, through the period of apartheid to a non-racial democracy. The advent of the “new South Africa” was greeted as a miracle by Rosemary. Her Catholic faith and her professional choice bound together ideas of service and a commitment to equality. When she chose to marry Koos, she found a partner with similar convictions.

As a lecturer in physics at Stellenbosch University, Koos spent after-hours teaching mathematics in the local township, Kayamandi. He did not support the National Party and was shunned by many of his colleagues as a result.

I interviewed Rosemary in 2019. She provided some details of her social and political life.

“At Rhodes through the Catholic Club, we had a meeting with the Catholic Club from Fort Hare. We went to Fort Hare and had a picnic, and that was a groundbreaking experience for me.

“It was the first time I’d mixed with black people on the same level, not as a servant… It was groundbreaking for me because it was the first time I was meeting black people who were like me, students studying similar things, and we discussed subjects and what we liked and so on. I thought it was lovely and I think that was an experience very few, in the fifties, very few white girls anyhow, had.”

She also explained that she and Koos had been very involved with Beyers Naude in the Christian Institute, which was then banned.

“And that was a wonderful thing for Koos and me because, you know, I was a Catholic, he was Dutch Reformed, he didn’t go to church anymore because he was ashamed of the church’s role in the whole apartheid thing, sort of justifying it. And so people like Beyers Naude were heroes to him and he got very involved, both of us, so it was something we could do together and also in the Progressive Party.”

Once Rosemary ceased to work as a librarian, she found ways to use her skills for the good of others, serving for many years as a helper for the bookshop in Claremont run by CAFDA (Cape Flats Development Association). In 2011 Koos died of cancer and Rosemary faced the last 12 years of her life on her own, but with friends and family close by.

In her personal relations, two things stand out.

She made lifelong friends, some dating back to her days at Convent in Pietermaritzburg. One of these was Jeanette Brooker (nee van Boxel) who she knew for her entire life (they were born weeks apart in Johannesburg). Others she met as a boarder in primary school at Convent: Anne Misselhorn and Jeanette Biebuyck.

Rosemary with Trust and Myness at his first communion. (Photo: Supplied)

Reaching out across social divisions

Another was her willingness to reach across social divisions.

She became godmother to Trust, the son of Myness Mkandawire, who worked as a domestic worker for a neighbour, and with whom Rosemary attended Catholic mass for many years. She forged strong bonds with all the people she worked with – in the UCT library (Norma Read and Ann Hodge) and in her home (with Weston and Mustapha Solomons). These traits were evident at her memorial service.

Emanuel Mwabutwa, a Malawian medical registrar and tenant who shared the house with Rosemary, wrote: “Over the past 20 months or so we became good buddies. She was always warm, kind and friendly. Every evening, when coming back from work, I always looked forward to her smiles and waving, when passing through the alley between the garage and the garden, as she sat watching her favorite shows on DStv and YouTube.

“In her I observed a very strong and independent woman who cherished her independence. I was always in awe that she could ably drive a manual car, when I wasn’t 80% confident. I was also impressed with her love for reading. Through her, I saw the example of finding joy in the simplest of things.”

Mustapha Samuels, who took care of house repairs, remembered: “I will really miss her. She was really like a mum to me.”

For the memorial service at St Bernards Catholic Church, Newlands, Norma Read chose to read a poem written by Irish Poet John O’Donohue, after his mother’s death.

May the nourishment of the earth be yours,

may the clarity of light be yours,

may the fluency of the ocean be yours,

may the protection of the ancestors be yours.

And so may a slow

wind work these words

of love around you,

an invisible cloak

to mind your life.

Rosemary lived long enough to become a great grandmother (twice). She bore two children (Gavin and Karen), and in turn, they had four (Lucy, Nina, Georgina and Olivia) and two children (James and Christina) respectively. As one might expect, she was very involved in parenting and grandparenting, lending a hand whenever she could, and making sure that she kept in touch.

Shortly before she died, Rosemary bought the book edited by Mike Deeb: Reluctant Prophet: Tributes to Albert Nolan OP (University of Johannesburg Press, 2023). She had attended services led by Father Nolan and remained interested in history, and in the vision of a church that united people and led with courage towards an emancipatory vision.

Rosemary would have been surprised, no shocked, at anybody writing a piece such as this about her. She believed in her opinions and expressed them strongly, but she didn’t think she had much power or that she meant much in the broader scheme of things. She liked to be included, and in her life did as much as she could to include others.

In the language of today, her belief was in inclusivity and that all people should respect one another and live in peace. A good foundation for any possibility of peace and prosperity, in South Africa and the world. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

What a lovely gentle peace, about a life well led, in these frankly horrible times. Life/Lives count everyone.

Well written and Rosemary well lived

The Guardian (UK) has, in their obituary section, ‘Other lives’. This would have been published there. Thank you for a well written, informative tribute to an, evidently, exceptional person.

Great writing , great tribute, Rob

She must be beaming by now.

I loved this article, reading about how people stretched the limits of their social and cultural environments to do good, decent, simply human deeds and to make vital, sincere connections with fellow human beings in quiet ways. As an Afrikaner I am moved by Koos, who “trapped vas” and did the right thing. Thank you for publishing this.

Thank you for this wonderful article, it was lovely to read it and discover more about Rosemary with whom I briefly worked at UCT library. I also didn’t know that she had such strong connections to Pmb which is where I grew up and still have family, and wish that I had known that at the time. My condolences to her family and friends (Norma!) who will surely miss her.

We need more people with those standards! Condolences to her family. She was a wonderful human being.

Can you imagine not being able to be a teacher because she was married? What a craziness that was!

I loved this, and some weird coincidences with my mum. She was born in 1930, her dad worked on the Railway. She lived in Pietermaritsburg for some time, my grandparents are buried there. She also worked in Jhb Public Library when I was a child (would have been in the 60s). She was politically active with the PFP and later the DA.

Nice tribute, Rob. Keep well.

A life well lived. Thanks for sharing. MHDSRIP.

Such a tender, thoughtful piece – a delightfully gentle read, in these turbulent times. Thank you, Robert.