BOOK EXCERPT

Black pride and defiance of political oppression, all for the love of nonracial rugby — ‘Rugby, Resistance and Politics’

Central to the transformation of sports towards nonracialism, Dan Qeqe paved the way for the mainstreaming and liberation of black rugby and cricket players in South Africa.

Daniel Dumile Qeqe (1929-2005), aka “Baas Dan” or “DDQ” – a local Port Elizabeth legend whose achievements had national repercussions that continue to this day.

Qeqe’s struggles and triumphs ran the gamut of political, civic, entrepreneurial, sports and recreational liberation activism in the Eastern Cape.

Rugby, Resistance and Politics tells the story of Qeqe’s life and times, and at the same time becomes a people’s history of Port Elizabeth. In the book, Buntu Siwisa describes how Qeqe co-engineered the birth of the KwaZakhele Rugby Union (Kwaru), a pioneering nonracial rugby union that was also a political and social movement.

Kwaru became a vehicle for political dialogue and banned meetings, providing resources for political campaigns and orchestrations for moving activists into exile. But Rugby, Resistance and Politics is also an attempt to understand a man of contradictions. Qeqe was known to be generous and kind to a fault. And yet he was also the “indlovu”, an imposing and authoritarian elephant, decisively brutal and aggressive. Then there was the side of Qeqe as a man whose actions were not in keeping with the Struggle, and the book narrates his role in “collaborationist” civic institutions and in courting reactionary homeland structures.

Yet, through all that, Qeqe was a signal actor in the emancipation of rugby in South Africa.

Read the excerpt below.

***

Introduction

Early on the evening of 8 September 1975, Dan Qeqe stared up at the headlights of all his cars flooding back at him. He had fetched them from his home in the upmarket suburb of Thembalethu in New Brighton, and driven them to the makeshift stadium in Veeplaas. Much the same had been done by all the other car-owning officials, players and supporters of the four-year-old KwaZakhele Rugby Union (Kwaru). Their vehicles had joined Qeqe’s to line the perimeter of the temporary stadium and light up the field with their headlights. The alpine-bright deluge provided adequate light for this night of a historic game of rugby.

The short and stocky 46-year-old Qeqe, commissioned by Kwaru’s executive committee, had flattened the ground, planted the grass, built the grandstand, and fenced the ground using corrugated-iron sheets. Some of the panels were new, but many had been bought from scrapyards in the Port Elizabeth and Uitenhage areas. The stadium had turned out a seating capacity of 6000.

But all the makeshift plans belied a soulful extravagance. The night’s game had been preceded by a series of political and legal tussles that threatened to overshadow what the black people of Port Elizabeth held dear. This was set to be a feast of rugby, the significance of which reached far beyond the clear-cut simplicity of a single game. The effects were already finding expression in the brewing local and national politics and sociologies never before generated in modern sport.

Reeling from a ban on using the Zwide Stadium, a municipal sports ground, Kwaru had had to quickly find a new stadium for their game, its tussles with the Port Elizabeth municipality ending in a bruising court loss for Kwaru. The ban had been instigated by Kwaru and the non-racial stance of the South African Rugby Union (SARU) in refusing to lend its players to the Leopards, the state-owned black rugby team of the South African African Rugby Board (SAARB), to play in the British Lions tour of 1974.

The event of this night – a South Africa (SA) Cup Final match between Kwaru and the Tygerberg Rugby Union (TYRU) of Cape Town, simply known as Tygerberg – had special meaning, lending to a new sense of people’s ownership, of community representation, black pride, the defiance of an oppressive political authority, all for the love of non-racial rugby. The SA Cup was sponsored by SARU. Having changed its name from the Rhodes Cup in 1971, SARU’s premier SA Cup was sponsored by Atkinson Motors in Cape Town.

Shebeens, taverns, dancehalls and various other entertainment centres in Veeplaas, New Brighton and other townships had closed for the night. Many had clamoured to the makeshift stadium. Others had turned on their radios in the comfort of their homes to listen to the Radio Xhosa broadcast of the game. Rather than risk having to settle for uncomfortable seating or standing spots at the ground, many spectators had hurried to take their seats immediately after returning from work. Some had arrived promptly after completing their chores and other daily responsibilities.

Mrs Jumartha Milase Majola, Qeqe’s long-time friend and neighbour, and director of the Ivan Peter Youth Club in New Brighton, had, along with Mrs Rose Qeqe and friends, prepared hot meals for the administrators and dignitaries. Abdul Abbas, president of the nonracial SARU, was in town, accompanied by senior SARU officials. Other sports and political struggle dignitaries had come from even further afield.

Methods of gate keeping and entrance-fee collection were as improvised as the temporary grounds. Qeqe and Kwaru officials, with hats in hand, made their way around the fence collecting money and, despite no visible gate, spectators dutifully paid their gate fees. Some of the money collected came in as donations from non-racial rugby lovers who had come from towns and cities of the Eastern Cape to watch the game – all in support of continuing with the building of the new stadium. For other non-racial sports liberation activists, Qeqe’s erection of a stadium made a clear and profound statement: ‘that actually you don’t need to have everything before you do things. Look at me, I’m doing it. I’m building a stadium’.

The Kwaru executive committee, to be seated on the grandstand with Qeqe, who was not in the executive committee, moved around, finalising preparations for the game. Arthur Sipho ‘Mono’ Badela – president of Kwaru, charismatic, politically active, and a ‘true blue African National Congress (ANC) man’ – turned up in a suit, as he almost always did. As a journalist on Port Elizabeth’s Evening Post, Mono Badela had defiantly defined Kwaru’s non-racial stand against the local and national state onslaught over the past four years.

Seated on the grandstand was the rest of the Kwaru executive: vice-president Wilkinson M Maku, treasurer Newman Grawana, secretary-general Samuel Nghona, assistant secretary Bruce Mahonga, recording secretary Daliwonga Siwisa, match secretary Koks Mtwa, chairman Lawrence Jack, trustees Thomas Sullo and Morris Peta, senior selectors Sipho Nozewu (also coach) and Hamilton Madikane, and junior selectors James Mtanga and Zweli Wabana.

Despite the festive mood, Qeqe, Badela and the Kwaru executive committee looked on pensively. This was going to be a record-setting game in various ways: not only to clinch Kwaru’s playing prowess by winning the SA Cup for the first time, but also to redeem itself from a self-inflicted shame of the previous year’s SA Cup Final match against Western Province. Perhaps as an act of desperation in a tough, neck-and- neck SA Cup Final in 1974 and in apparent protest at an award to Western Province of an easy penalty point right in front of the posts, Kwaru’s Themba ‘Sgabadula’ Ludwaba, a scrumhalf and flanker, had sat on the ball mid play time, refusing to let Western Province kick the penalty ball to the goal post. The 1974 final match produced no winner, and the trophy was shelved. In all likelihood, Western Province, which had had straight SA Cup wins since 1971, would have won.

Ludwaba, regarded as an ‘outstanding achiever,’ was an amazingly tall player, fiercely muscled, agile and a terror to any rival team. Nonetheless, his mischievous antic on the field had cost Kwaru, ending with disciplinary action at the table of SARU administrators. Qeqe and the Kwaru executive committee, sitting on the grandstand on match day in September 1975, were eager to redeem Kwaru’s standing.

The ground’s seating capacity of 6000 had swiftly swelled to about 20 000. Milling around the grandstand and all around the corrugated-iron fence, spectators erupted in awe and excitement at the ‘Rolling Maul.’ This was the pinnacle of the Kwaru team’s showmanship – a grand entrance akin to a long, fast-moving worm, with the ball moving fast from one player to the next. It was also executed as a winning movement towards scoring at the try line.

Peter Mkata, part of the Rolling Maul, was Kwaru’s premium favourite alongside Ludwaba. Mkata began playing for Kwaru in the early 1970s as a centre and fullback, but proved to be a brilliant flyback. An elusive but direct runner, his excellence lay in tackling, well supported by his nimbleness and a brilliant sense of participation. Also part of Kwaru’s force was A Lefume, a scrumhalf (known as Zanemvula and nicknamed Kenya) from Ginsberg, King William’s Town, and ‘his performance at scrumhalf was noteworthy’. Another crowd favourite was Wilfred Khovu, Kwaru’s front-ranker.

Qeqe himself – from New Brighton – had honed his rugby-playing skills and fitness from 1961 when he joined the Spring Rose Rugby Football Club. Welile Jeremiah ‘Bhomza’ Nkohla, another Port Elizabethan in the team and another of Kwaru’s favourites, played club rugby in the Kwaru-affiliated Orientals Rugby Football Club. His well-rooted role in the team was as eighth man. Ntonga ‘Stix’ Singata, Kwaru’s flyhalf, was another popular player from the Kwaru-affiliated Walmer Wales Rugby Football Club.

Tygerberg, of course, boasted its own star line-up. JP Jeposa was a well-honed and experienced hooker, with Peter Jooste, one of the most experienced Tygerberg players, coming in as a lock. Millen Petersen was a strong scrumhalf who was considered ‘strong and sure’, particularly in his long, accurate passes. Another prominent Tygerberg lock who graced the field against Kwaru was Daniel ‘Spook’ September.

As the game went on, at a neck-and-neck pace, Qeqe’s tough training and coaching regimen, placing a premium on physical fitness, stamina and endurance, gave the Kwaru team an edge over Tygerberg. However, in the second half of the game, it was Kwaru’s Ntonga ‘Stix’ Singata who secured Kwaru’s win with a final score of 15–9. Not long after Singata’s winning try, the game was over. For the first time, SARU’s youngest and first black affiliate had won the SA Cup. And, with Singata’s score, Kwaru had redeemed itself.

The triumph of that night, however, huddled alongside the fear of what might have happened. Qeqe or Badela or any of Kwaru’s executive committee members and administrators could have been arrested and thrown into jail for their defiance in playing non-racial rugby. Even worse, their actions could have been seen as a dastardly and daring appropriation of land in order to defy the laws of the state. Louis Koch, chief director of the Cape Midlands Bantu Affairs Administration Board, had already tried to sabotage the building of the stadium, but had failed against the fury and determination of Qeqe.

Fortunately, the Security Branch did not, however, swoop in on them. Instead, the wild, uproarious cheers heralded an incredible feat, an achievement that had never been seen before in South Africa. This was a new phenomenon, the start of the journey of one community stepping beyond the crosscurrents of the social, cultural, political and sporting worlds. A new era of Kwaru rugby had been launched, one that sought to consolidate the organisation’s iconic status as one of black pride, a culture of political defiance, and an expression of community cohesion. These attributes all coalesced around the amazingly selfless acts of Dan Qeqe.

That night, Qeqe, Kwaru’s executive and all the players and administrators moved on to David Mbane’s business premises, Melisizwe Butchery, for celebrations. Mbane, Qeqe’s contemporary on the rugby field, had played for Eastern Province in the 1950s and 1960s, as well as in the major African Cup competitions of that time. In his playing days, he was considered ‘the mobile and tough Eastern Province forward’. But on that evening of Kwaru’s victory, he was one of Spring Rose’s administrators, a prominent businessman, and served with Qeqe on the Port Elizabeth Joint Bantu Advisory Board.

Monumental gate takings of R11 578 had been further cause for celebration. In the room above Melisizwe Butchery, Abbas named the makeshift stadium ground the Dan Qeqe Stadium. Standing to address the crowd, he said, ‘I want you to adopt that name and leave it to the authorities to remove it even if by forcing us to play in the streets.’ And so, inadvertently, Qeqe had lived up to the meaning of his middle name, ‘Dumile’, meaning, ‘famous’. At the height of apartheid, this black man had come to have an entire stadium, built on land literally appropriated by the people, named after him. This was the beginning of a journey of challenges, joys, fears, loss, pain and history-making for Dan Qeqe and the people of Port Elizabeth. DM

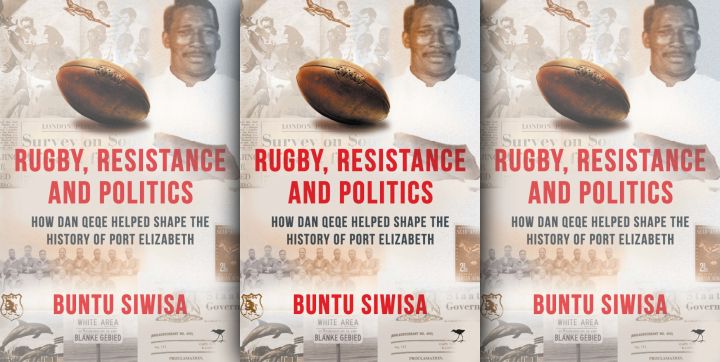

Rugby, Resistance and Politics: How Dan Qeqe helped shape the history of Port Elizabeth by Buntu Siwisa is published by Jacana Media (R196). Visit The Reading List for South African book news, daily – including excerpts!

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

To the Author: Is this an exact extract from the book?

“.. Another prominent Tygerberg lock who graced the field against Kwaru was Daniel ‘Spook’ September”.

The Daniel ‘Spooky’ September that I saw play was a brilliant fullback and goal-kicker. Can any other reader confirm if there was another ‘Spooky’ September that played lock?

So much we don’t know that was hidden from our schooling by the bloody Nats!!!!

What might have been!! …. I never forget the day I turned out playing for a uni Law team (late 70s), a pretty good touring team … & we were smoked by a rangy, Coloured player. I can’t even remember what position he played. He could score going over us … around us … & through us, all done with athletic joy. To be honest, it was a late, startling revelation as to the potential that the country was squandering. (The BS of the day being that Blacks & Coloureds played soccer!!) The myths that one clings to … sigh …

We had very talented and some amazing players. A real pity you never got to see more of them. I saw Rob Louw at a few SA Cup games.

Enlightning