WASTE OPPORTUNITY

A look at how surplus food can be used to address the crisis of hunger and malnutrition in South Africa

South African food producers ‘lose’ or waste about 10 million tonnes of good-quality food a year, while more than 20 million people go hungry every day. Why are the two issues not being connected, and could this surplus food help to solve South Africa’s chronic hunger problem? FoodForward SA is a ‘food banking’ organisation already making an impact. Its managing director, Andy du Plessis, told Maverick Citizen how it works ‒ and why it is not yet a big part of the country’s solution to hunger.

‘When a farmer starts harvesting he’s got no control over when stuff ripens,” Du Plessis explains a few days after World Food Day (October 16). “Often when apples, say, ripen at the same time, he has to take it off the tree irrespective of whether it will be sold or not.”

Du Plessis explains how “on-farm surplus” happens for farmers growing fruit and vegetables for certain retailers.

“They want a very specific type of apple or tomato – a specific size, unblemished, with certain colour specifications.” The result is that quite a large portion of on-farm surpluses has to be dumped after the harvest. It goes into a local landfill: “We’re talking about massive amounts on a daily basis ‒ agri-bins with loose fruits, tonnes and tonnes. We want to intercept that while they harvest, so that they donate those surpluses to us.”

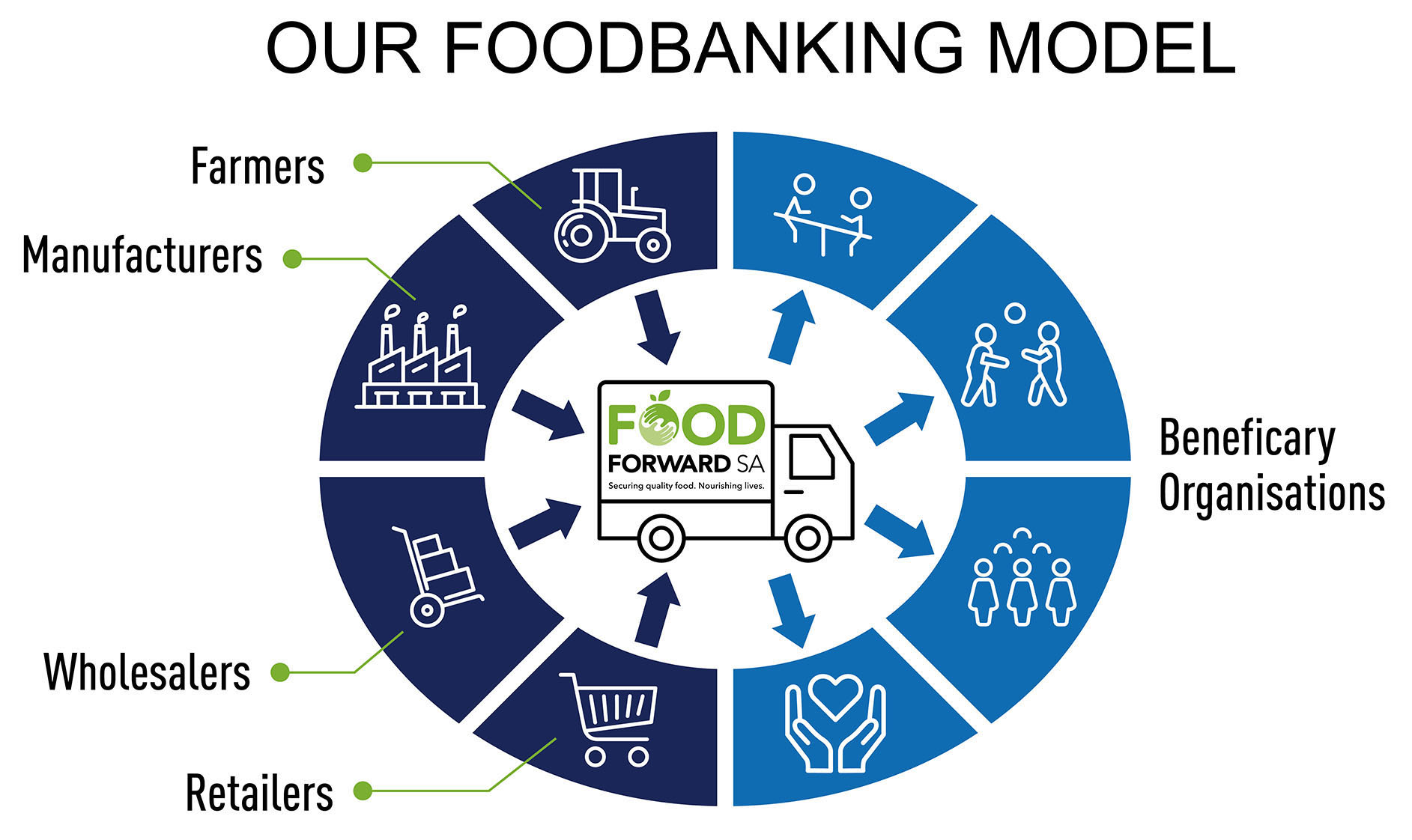

Using on-farm surplus is a cornerstone of the FoodForward SA (FFSA) methodology. It is one of South Africa’s food banking organisations that redistribute perfectly good-quality, safe, fresh food that would otherwise go to waste because of retailer specifications or overordering, or ‒ in the case of manufactured food products ‒ because of overproduction or incorrect labelling. The “rescued” food goes to people and entities (such as early childhood development centres) that cannot access or afford the nutritious food they need.

Workers and volunteers in a FoodForward SA warehouse pack pallets of food for transport to beneficiaries. FoodForward SA mandates that at least 85% of all food redistributed must be nutritious, which means that donations of foods high in unhealthy nutrients are limited by the organisation’s systems. (Photo: FoodForward SA)

Who goes hungry in South Africa?

One-third of all food produced in South Africa – 10 million tonnes – is “lost” or wasted in our food system every year, while more than a quarter (27.5%) of South Africa’s children are stunted due to malnutrition.

Along with the food a “huge opportunity” is lost, Du Plessis says. The food, redistributed, could contribute to solving the enormous challenges of widespread hunger, malnutrition and food insecurity, as well as the increased environmental impact of uneaten food due to greenhouse gases emitted during growing, harvesting and processing, and by food rotting in landfills.

“There are literally hundreds of thousands of connections to food surplus across the food system,” Du Plessis says, “from farmers and packhouses to producers, manufacturers, retailers, ‘quick-serve’ restaurants and the hospitality industry.” One of the main reasons for food loss and waste is that “a lot of those actors are not donating those surpluses”.

Given the yawning “food poverty gap” (the gap between what people earn and what they can afford to spend on food every month) that has continued to grow over the past 10 to 15 years, the need for food redistribution is growing larger and more urgent. This is partly because of growing economic inequality (South Africa is the most unequal country in the world, the World Bank reports), and partly because of unemployment since the Covid-19 pandemic.

Before Covid-19, an Oxfam report said, 14 million people in South Africa were food insecure. A further 14 million were “at risk” of food insecurity if exposed to “shocks” such as pandemics, climate catastrophes and load shedding. “That’s exactly what happened with Covid-19,” Du Plessis says. In the latest census, Stats SA puts the number of those experiencing food insecurity at 23 million.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Eight million hungry children: New report about the shocking impact of poverty on young South Africans

“Our view is that that number has grown quite dramatically to where it is today,” he says, putting it at 30 million – half the population.

FoodForward SA’s roots

The organisation’s seeds were sown in 2001, when Bianca du Plessis (no relation), a Stellenbosch University film student, started working at a local film studio and noticed large amounts of food going to waste on film sets. Initially on her own, and soon with help from one or two others, she systematically started doing the rounds of local film sets, collecting surplus food from the caterers, and taking it to nonprofit organisations (NPOs) she knew had a need for it.

Soon after, her NPO began to scale up with the help of finance expert Alan Gilbertson, a former director and chair of the Global FoodBanking Network. He bought two bakkies with his own money, and committed to three years of funding for the fledgling NPO.

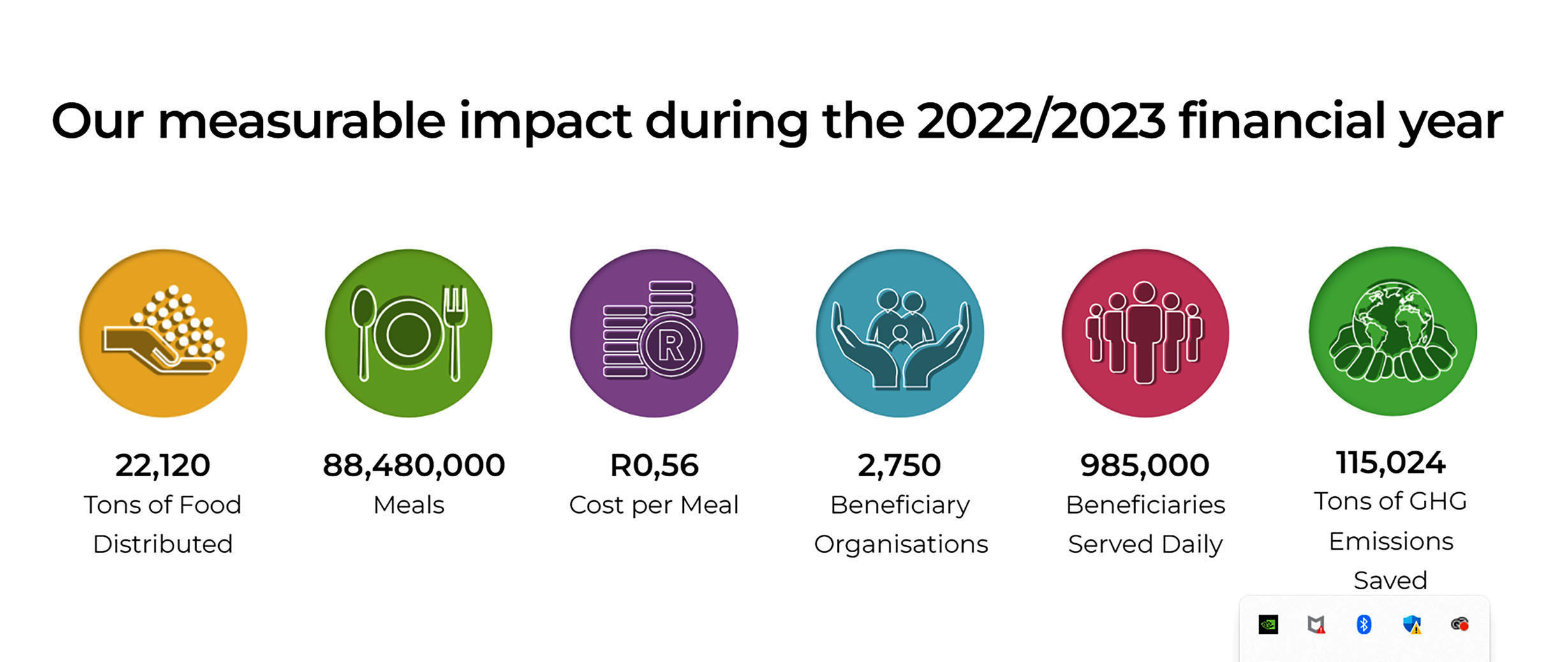

FoodForward SA routinely measures its impact and its cost effectiveness. One of these measurements is of greenhouse-gas emissions saved as a result of food rescue, partly from avoiding methane emitted from landfills where surplus food is often dumped if it is not rescued. (Image: FoodForward SA)

Feedback Food Redistribution, as it was called then; the Lions Food Project; the Robin Good Initiative and the Johannesburg Foodbank amalgamated to form FoodBank South Africa in 2009. It was later renamed FoodForward SA. Today it has a base in each of the country’s nine provinces, distributing food to 2,750 beneficiary organisations and serving 985,000 people every day.

In 2022, its “measurable impacts” included almost 90 million meals (88,480,000) and saving 115,024 tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions.

Professionalised and solvent

When Du Plessis came on board in 2013, his mission was to turn the organisation around from a loss maker into a fully professionalised, solvent entity – and FFSA’s cost-effectiveness is testament to his success. The cost of a meal has dropped from R1,73 in 2013 to 56c 10 years later (an even greater improvement if considered in real financial terms).

Du Plessis has also introduced standard operating procedures, more rigorous verification of beneficiary organisations, expansion of FFSA’s food supply partners and a broadening of its financial donor base.

South Africa has no regulations either proposing or mandating how to manage food loss and waste.

It relies mostly (75%) on donations from corporates, trusts and foundations, and on interest income and fees for services such as distribution (FFSA stores and delivers food to schools selected by the Kellogg’s breakfast programme in partnership with the Department of Basic Education). In addition, Du Plessis says, each beneficiary organisation pays a monthly membership fee (15%).

The potential for this model of food rescue is enormous, he says, and FFSA is certainly not the only organisation doing this type of work (SA Harvest is another) while countless nongovernmental organisations feed children and families within their local areas or communities.

Two obstacles

So, what is stopping South Africa from starting to solve its massive hunger and malnutrition problems by repurposing the 10 million tonnes of fresh food wasted every year? It is more than enough to provide three nutritious meals a day to the more than 20 million people who go hungry every day.

Two things, Du Plessis says.

First, the agricultural and food production sectors of our food system need to improve their coordination and communication in order to identify and target food losses at the right point in the food value chain, in a timely manner.

“The largest amount of surplus food loss and waste is happening on the manufacturing side – so the largest opportunity lies there. We need to connect the dots better – there are huge amounts of surpluses and we need to do better at extracting them.”

The South African Bureau of Standards has agreed to put together a South African National Standard (SANS) for food donations “that’s going to be a game changer”, Du Plessis says. “It will give clarity to food system actors about what to do and how to do it. Our view is that it [a SANS] is going to lay the foundation for regulatory changes to the Foodstuffs Act.”

When will the government join the party?

South Africa has no regulations either proposing or mandating how to manage food loss and waste. Even some countries without huge hunger problems have them. In February 2016, in a unanimous decision, France adopted the so-called Garot Law, which forbids supermarkets from destroying unsold food products that could be donated to NPOs.

Italy did the same six months later, in an attempt to drastically reduce food waste as part of complying with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), whose SDG 12.3 on sustainable consumption and production targets halving food loss and waste by 2030.

Though South Africa has a shocking hunger and malnutrition problem, and is a signatory to the SDGs, the government has made no changes to food-related regulations aimed at achieving the sustainable consumption and production goal – nor fundamental changes to solve hunger at the same time.

‘Food banking’ is a way of rescuing perfectly edible, nutritious food that would otherwise be wasted, and redistributing it to vetted beneficiaries, connecting ‘a world of excess to a world of need’, as FoodForward SA puts it. (Image: FoodForward SA)

High hopes for the Health Department

This could change, though, because the Department of Health may be about to get on board.

“The Health Department was here and they saw for the first time how much food was able to be recovered,” Du Plessis says. After that visit, FFSA made a submission to the department as part of the public consultation on a new draft regulation, R 3337, which is a food-labelling amendment to the 1972 Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act.

FFSA’s submission suggests that the final regulation states clearly that food donations must be encouraged across the food system, and that the regulations must stipulate that food past its “best before” date is still edible and usable (up to a defined point). “Let’s hope that the department will look at that,” Du Plessis adds.

However, food rescue is not a silver bullet that can solve all South Africa’s hunger and food insecurity problems. Children in particular still remain vulnerable due to their unique and comprehensive needs.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Subsidising these 10 essential products could help stave off malnutrition in SA, say civil society groups

Chantell Witten, a Wits University lecturer in community paediatrics, is of the opinion that, although food rescue and redistribution initiatives “play an important role to alleviate short-term hunger”, they cannot fundamentally address child malnutrition because of their short-term nature. They should complement longer-term solutions such as food vouchers, food parcels and on-site meals (such as school meals for children), she says. DM

Adèle Sulcas is a global health policy writer, and an editor for Daily Maverick’s Food Justice Project and Wits University’s Centre for Health Economics and Decision Science.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

What a fantastic initiative and a game changer for those that need. There is still hope in SA whilst organisations like this exist.

Addressing food-security and hunger, is one of the most pressing needs in South Africa. Bravo to FFSA!

Inspiring stuff

THe answer to huge problems are so often staring us in the face