BUSINESS REFLECTION

After the Bell: Using a word cloud to work out why SA’s industrial sector is in decline

SA’s industrial policy has been a terrible failure and it’s worth asking why. It’s particularly interesting because successive trade and industry ministers have been enthusiastic proponents of the notion of industrial policy. They really care about it and are keen advocates of government intervention. And yet the failure continues.

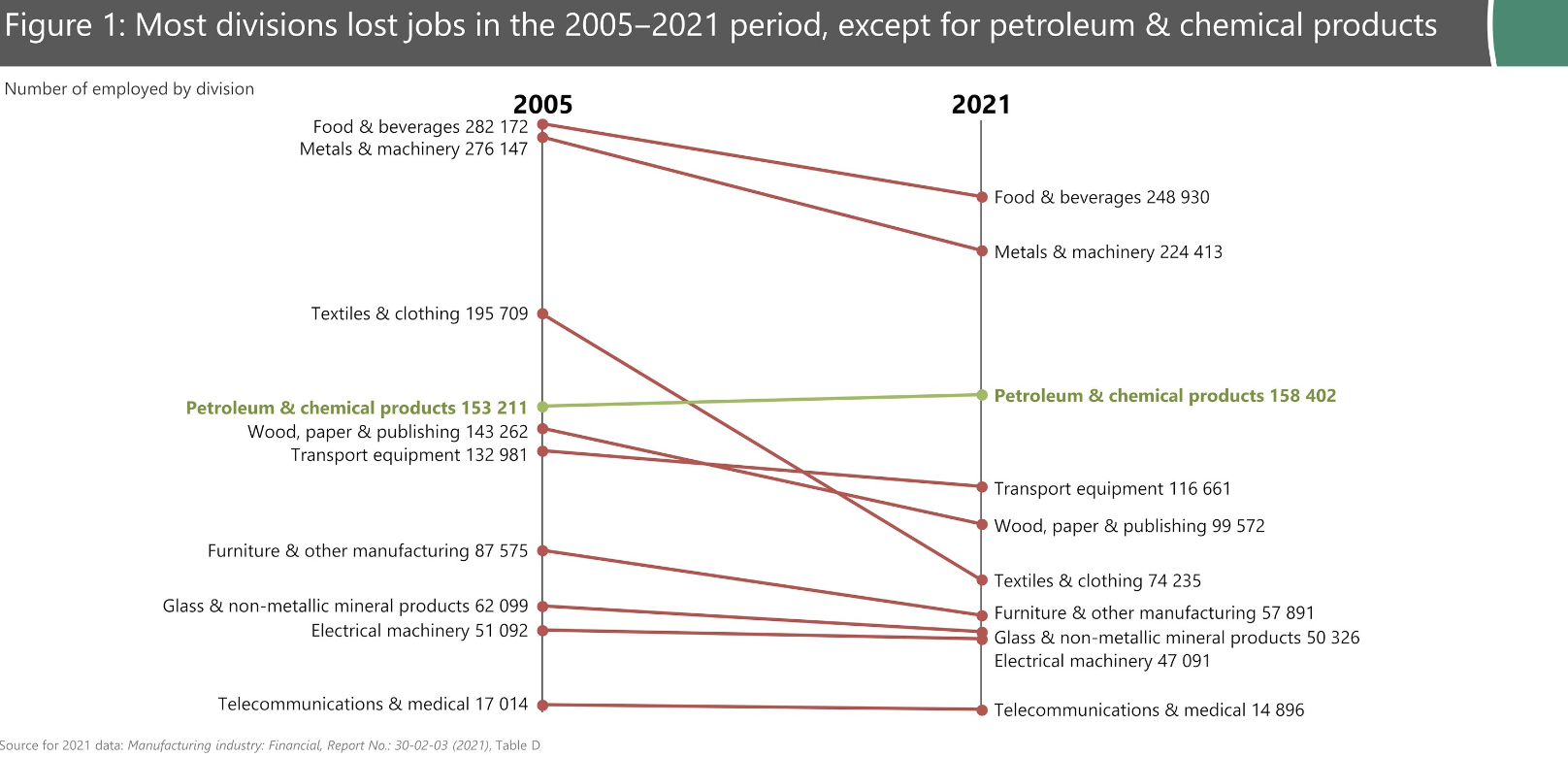

Consistent data from Stats SA shows that in almost every industrial sector, there have been declines in manufacturing employment — even as SA’s population increases at a fair clip. In 2005, industry employed 1.4 million people. In 2017, 1.2 million were employed, declining again to 1.1 million in 2021. The sector has lost almost 309,000 jobs over a 16-year period, roughly a quarter of all industrial sector jobs.

So now of course, it’s easy to blame SA’s government policies for the decrease, but the truth is that manufacturing jobs all over the world have been under pressure as these jobs have been absorbed by China. SA’s large and growing trade deficit with China demonstrates this effect, as does a sectoral breakdown. The biggest portion of the job losses in SA are in the clothing and textile industry — precisely the industry where China has excelled.

In addition, SA’s industrial sector has always been strongly linked to the mining sector, which has been in dramatic decline over the past decade. Third, SA’s industrial output is, of course, heavily affected by increasing load shedding and state-owned enterprise dysfunctionality. And fourth, SA’s debilitating labour policies tend to hit the industrial sector hardest.

But what about the ideological question? Is the government’s statist approach, outlined most clearly by the former trade and industry minister Rob Davies in the foreword to the 10-year review of SA’s Industrial Action Plan, published in 2020, to blame? As a free market-orientated person, that would be my instinct, but in all honesty, it’s not quite that simple.

The first issue is that a recent academic study seems to show that trade policy, in some circumstances at least, does work — although it’s risky. Stellenbosch University economics professor Johan Fourie points out in a recent blog post from his “Our Long Walk” series that no less an international figure than Harvard economist Dani Rodrik has just published a new research paper with Réka Juhász and Nathan Lane. They found that industrial policy had been dismissed too quickly by academic economists.

Much depends on what you want industrial policy to do. The academics find there are at least three good reasons for industrial policy: externalities, coordination failures and activity-specific public inputs. I get so excited when economists start talking about “externalities” (not), but I suppose they are important.

For example, some businesses can contribute to national security, but you won’t see that in their financials. The government could and perhaps should support them. The government can also intervene to get a new industry going, by making sure there are complete logistics and component lines available. And it can help with specific training to maximise the utility of new sectors.

The danger, which Rodrick and his co-authors acknowledge, is that industrial policy can “open the door to self-interested lobbying and political influence activities, diverting the government into activities that enrich private interests without enlarging the social pie”.

Doesn’t that sound quite a lot like SA? Fourie makes what I think is an important distinction in the aim of industrial policy. In the 20th century, many Asian countries built their success on export-oriented policies, whereas many Latin American and African countries attempted import-substituting policies and failed.

So, what has SA been doing? Fourie says Davies’ explanation mentioned above seems to focus on both import substitution and export orientation. That is certainly my experience of how Davies and his successor Ebrahim Patel verbalise the government’s thinking behind its heavyweight interventionism; it’s just not very clear. Both have tended to borrow a bit from everywhere, trying to fashion themselves as a kind of Trade Minister for All Seasons.

Fourie tries a different approach, which I think is very interesting, and that is to use natural language-processing techniques to investigate what politicians say and what the real policy might be. This is like a word cloud and it can be very revealing. He asked Phronesis Analytics, a Pretoria University-based start-up, to undertake a topic analysis of political speeches and parliamentary debates in South Africa. They did so for an entire database of speeches and documents from 2012.

The result was four stand-out topics: “youth”, “special economic zones”, the “green economy” and “black industrialists and BBBEE”. Fourie says this indicates SA is not focused on improving exports but rather on redistribution. Most worryingly, the word “technology” is notably missing from discussions about industrial policy in SA.

This makes absolute sense to me: if there is a function for industrial policy, it is, in essence, to improve business confidence and the business environment to encourage them to expand, invest and hire. But successive trade and industry ministers don’t see that as their primary responsibility. Instead, they view transformation as the absolutely overwhelming priority. But because their transformation methodology has been restrictive, poorly thought out, poorly administered and essentially hostile to existing business, the result has been limited transformation and a distinct decline in manufacturing.

There are many reasons for SA’s manufacturing decline; poor policy is definitely one of them. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Could’ve saved you all the time spent writing this article. Here are 100 reasons for the decline of our industrial sector and all of these are the ANC.

I rebuilt my factory. The quality of staff was increasingly poor, and we were hiring more and more staff just to check the work the first team had done, plus training, plus security. Then the unions cut up all rough as well. It got to the stage that despite the wage advantage of SA staff I could almost import cheaper from the UK than manufacture here.

The new factory is almost entirely automated. 200 jobs went, now staffed by 20 excellent staff, occasionally supplanted by agency.

No more union issues, no more money to spend on training basic skills, no more huge security bills. That’s where the jobs have gone.

The four stand-out topics say it all, the anc and their ilk have built nothing, created nothing (other than poverty and misery) and developed nothing, their only interest is to take what others have built