WOMEN IN SCIENCE

SA rocket scientist’s bespoke nuclear fuel powering potential to settle on the moon and beyond

At Bangor University in Wales, Phylis Makurunje is developing tiny nuclear kernels that will get us into space faster, farther and more cheaply. Her work could revolutionise how we explore the universe.

When South African engineer and scientist Phylis Makurunje read the advert for a position with the Nuclear Futures Institute at Bangor University in north Wales, her first reaction was one of disbelief, followed by great excitement. “It might have been written for me!”

Three years later, Makurunje is going places. If not to space itself, then at the very least to the upper reaches of astrophysical research, as her team’s work on nuclear fuel for spacecraft is gaining international attention. The fuel comes in the form of so-called Triso (TRi-structural ISOtropic) particles that pack a punch way beyond their size.

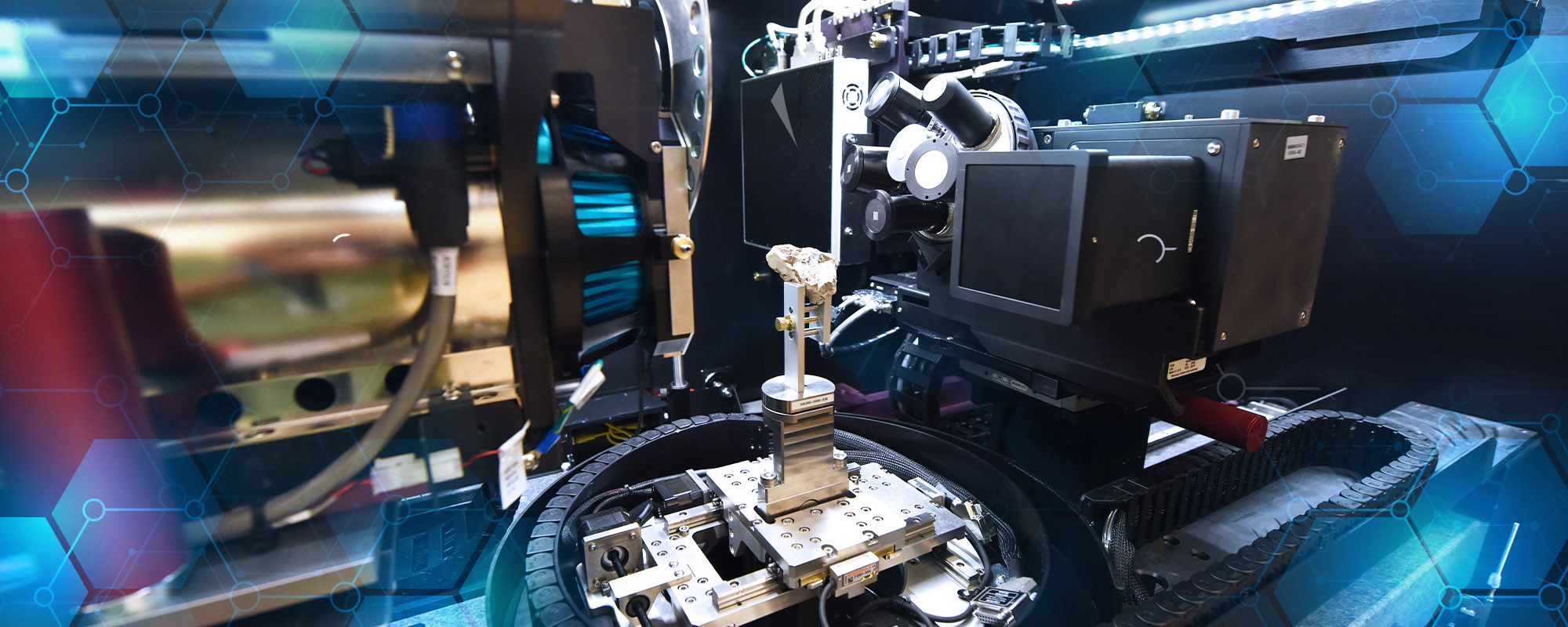

About the size of poppy seeds, the spherical particles comprise a uranium fuel kernel enclosed by layers of carbon- and ceramic-based materials manufactured using modern additive technology.

Makurunje’s work with the institute is part of an international collaboration involving Rolls-Royce, which is developing micro nuclear reactors, Nasa, the UK Space Agency; the US National Nuclear Laboratory and the Los Alamos National Laboratory.

If they get it right, the first nuclear-powered rocket will head for the moon by 2030. After that, perhaps Mars?

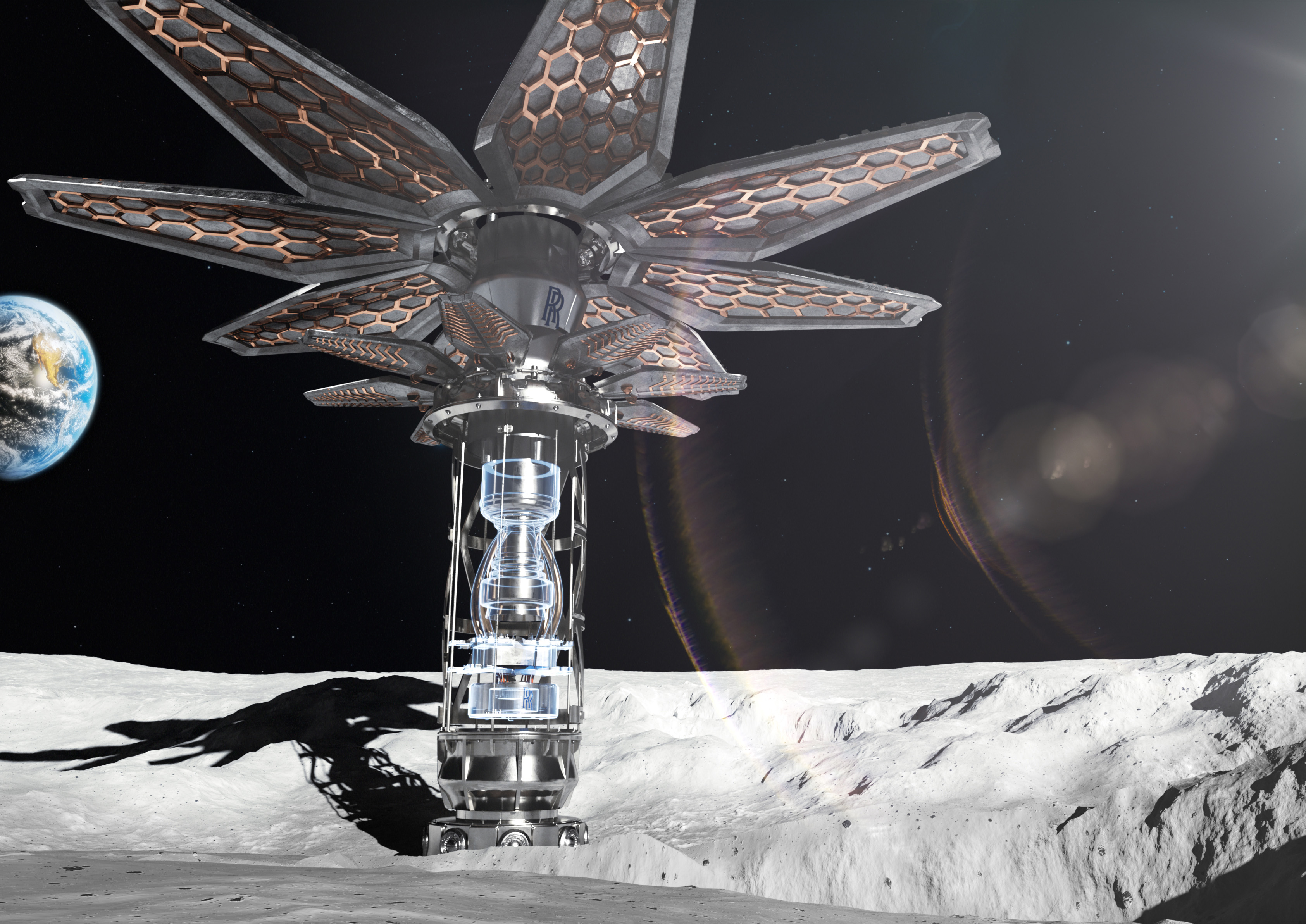

Artist’s impression of a “space flower” micro-reactor that might one day be used to generate power for a lunar colony. (Photo: Rolls Royce)

A dent on the universe

Simon Middleburgh, a professor in nuclear materials and co-director of the Nuclear Futures Institute, is lavish in his praise: “It’s so nice to see someone evolve from PhD student to a position where she’s given really difficult projects with challenging timelines, to watch her succeed.

“Phylis brings with her a formidable knowledge of ceramic materials manufacture for aerospace applications. She’s leading the international push for aerospace materials, so she has lots of buy-in and influence.”

Makurunje and her colleagues are exploring different ways of making the fuel kernels using modern additive technology in the form of 3D printers.

She elaborates: “Our goal is to develop a greener manufacturing method and make larger quantities per unit time. In other words, we’re looking for ways to reduce the cost of space exploration.”

The fuel kernels developed at Bangor University are undergoing tests in Rolls-Royce laboratories with a view to launch-readiness by 2030 at the latest. The company, with a 60-year pedigree in nuclear power, launched the microreactor concept in 2021.

Professor Simon Middleburgh and colleague at work in Bangor University’s Nuclear Futures Institute. (Photo: Bangor University)

Says Middleburgh: “We’ve made two prototypes — one of them an inert prototype that doesn’t contain any uranium to demonstrate the technology, and a uranium-containing version that will stay here at Bangor University for us to conduct testing. We’ve proved the concept and manufacturing techniques; now we need to work out how to achieve scalability and make it a commercial item.

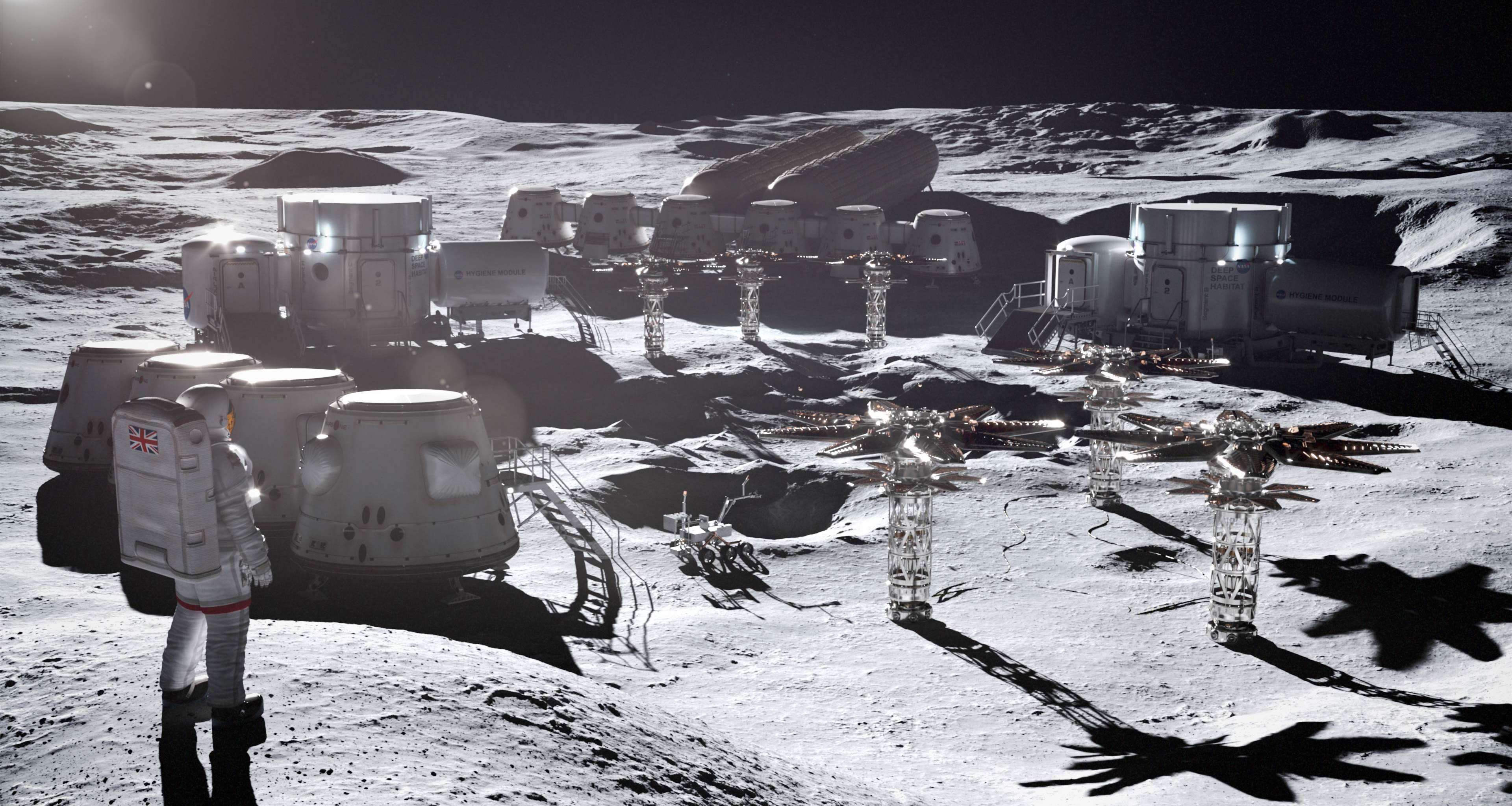

“We have a huge international team working on this. We need it on a launchpad in 2030 to go and look after the astronauts on the moon base, so we have a handful of years to go from lab-processing scale to something that we can really trust. It would be good to have a Rolls-Royce reactor on the moon. It’s something that will change humanity for the next 50 to 100 years if we get it working.”

Read more in Daily Maverick: Nasa’s Artemis mission – to the moon and beyond

Makurunje is clearly excited about her field of research. “You’re talking about planets beyond the Kuiper Belt… Is there life anywhere? Closer to home, and when it comes to exploring the moon, the focus has moved to business and using the moon as a base station or jumping-off spot. The challenges and opportunities are never-ending.

“We’re taking our research to commercial partners who speak business language and scalability. They don’t see a little bottle of nuclear fuel from our lab … they see a ton of it, and their question is ‘how to get there?’”

This vision of a future space colony inspires South African scientist Phylis Makurunje in her work at Bangor University. (Photo: Rolls-Royce)

Middleburgh interrupts, suggesting that Makurunje is downplaying her own contribution to the research: “She basically invented a new process to make these kernels at very low energy at very high throughput, so it’s very scalable. Previously, the national labs were turning out about 1kg of fuel kernels a week, whereas Phylis’s method produces about 1kg an hour. There’s novelty in the manufacturing, in the materials we’re using and in the application.

“We’ll be sticking these things on rockets to go to the moon and Mars and beyond. That’s where their robustness is really important. We need these things to deal with a launch failure; we need them to deal with an unexpected collision with the moon and not spread material all over the place.”

How many of these kernels would one need to propel one of Elon Musk’s rockets to the moon? Says Middleburgh: “Phylis is working on a project with the UK Space Agency to answer this very question. Each kernel measures less than 1mm, and each has to be perfectly shaped, so there would be millions of these little things.”

If all goes according to plan, adds Makurunje, the tiny fuel kernels would reduce the travel time to Mars from more than nine months to a window of four to six months. Aside from all the other hazards facing spacefarers, it means they would be exposed to considerably less radiation during the voyage.

Middleburgh stresses that the development of nuclear fuel kernels is by no means their sole concern. “The propulsion challenges are bloody difficult, but then there’s the power side of it. Once you get to the moon, how do you power your water generation; how do you produce food; how do you stay warm?

New X-ray techniques deliver novel images of Triso nuclear fuel kernels. (Photo: Idaho National Laboratory)

“If you stay in one place, the moon will be dark for two weeks in every month, so you would need tiny nuclear power stations — the size of this table — to generate electricity, and a few hundred kilowatts would power your moon base. We’re looking at the same type of fuels for that … millions of little poppy seeds to generate electricity and heat, and potentially working for about 15 years.”

It’s important to distinguish between power and thrust, says Makurunje.

“To take a rocket into space, you start with liquid hydrogen at cryogenic temperature, heat it to about 2,000 degrees Celsius, then expel it through a nozzle to produce the thrust. But when you’re producing power for operating a lunar station, for instance, you need a different system.”

Welcome to Wales. Okay, now climb that mountain

Makurunje remains mildly surprised at the rapid trajectory of her career. “Simon and his team wrote the best job advertisement I had ever seen. I had no intention of coming to Bangor, but the advert was so compelling that I simply had to apply. That was during the Covid-19 pandemic, and I had just submitted my PhD thesis at Wits.

“Then they offered me the job! That immediately expanded my horizons because I had never worked directly with nuclear technology, and it was a great opportunity to see how ceramics could be merged with nuclear,” she says.

Did her arrival in north Wales deliver a serious culture shock?

“Oh yes. As part of my initiation, I had to climb Snowdon — the highest mountain in Wales — with the team. They were much amused when I trailed behind, but it was a great opportunity for team bonding.”

When did she decide to become a scientist?

“I have always felt like I was born into it. My parents had science-based careers, and we had maths quizzes and games at home. When my sister started high school, she would come home and teach me fascinating physics facts and quiz games. My parents helped me with career guidance and I opted for engineering.

“Growing up, we had to make our own toys. But it takes a village to raise a child. In my journey, I was financially helped by many individuals and institutions. The list is really long, and I am so grateful.”

Does she hope to inspire other young South Africans to follow in her footsteps?

Makurunje replies: “This quote from Kalpana Chawla does it for me: ‘The path from dreams to success does exist. May you have the vision to find it, the courage to get on to it and the perseverance to follow it.’

“I would say, dream unreservedly. Dream the disruptive, the daring and the ‘impossible’ … something that makes the hurdles and challenges look too small to stop you.”

If she were offered an opportunity to travel to space, would she take it?

“Absolutely. What greater experience than the opportunity to see the blue planet from above and defy gravity?”

Finally, how about the Welsh language? Any hurdles?

“I can say Diolch (thank you). That’s a good start,” she says. DM

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper, which is available countrywide for R29.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

What a wonderful article about an incredible person. So uplifting. Needed that with so many terrible things happening in the world right now. Thank you.

Well done to Phylis, a wonderful achievement! I don’t want to take anything away from your goals, but shouldn’t we rather be fixing the problems on earth than spending billions of Pounds/Dollars/Euros on a project that will never happen? Space exploration is a luxury that we really can’t afford.

What an inspiring story, I wish you all the best Phylis and hope your story will inspire many more young people to follow your footsteps.