PUBLIC FINANCES OP-ED

Eight things you need to know about South Africa’s fiscal position

South Africa is not in an unprecedented crisis. The National Treasury has mischaracterised the state of public finances to create a sense of panic, and while we face fiscal challenges, indiscriminate cuts will make our situation much worse.

In recent weeks, the National Treasury — with support from the business press — has been touting the urgent need for deep budget cuts. To justify this, it has presented South Africa’s fiscal position as extraordinary and in “crisis”; some have claimed that the state has run out of money.

But cuts to social spending have direct negative impacts on people’s wellbeing and rights. They would further hamstring already compromised public services. In light of this, we investigated whether there is a fiscal crisis, as the National Treasury claims, and if so, whether its proposed cuts are the answer. We found that we are not in an unprecedented crisis, that the National Treasury has mischaracterised the state of public finances to create a sense of panic, and that while we face fiscal challenges, indiscriminate cuts would make our situation much worse.

There are clear alternatives to wholesale cuts, which would uphold rights, enhance wellbeing, and set South Africa on a path towards social and economic development.

This summary draws on a detailed analysis published by the Institute for Economic Justice.

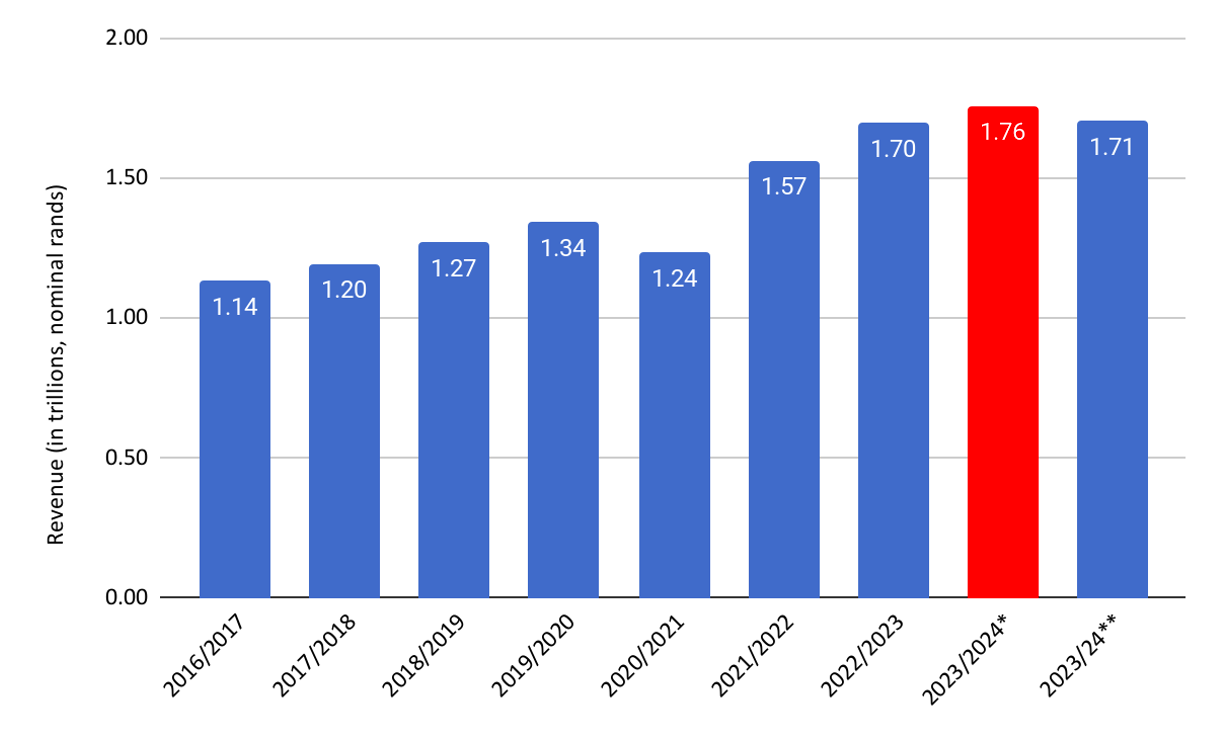

1 While below the Treasury’s target, revenue has not collapsed

Revenue will grow by only around 0.55% in 2023/24, compared to the approximately 4% growth that Treasury anticipated (see Figure 1). This means that revenue will miss the Treasury’s target by R54.2-billion. This does not represent a collapse in revenue. To put the shortfall into perspective, R54.2-billion is around half of what the government collected in revenue in November 2022 alone.

The revenue shortfall is mainly a result of the weak performance of the mining industry, the continued impact of load shedding, and unjustified changes to company tax. The mining sector’s stellar performance in the last two years weakened as the commodity boom slowed down in 2023. This led to lower-than-expected corporate income tax revenues and mining royalties. Value-added tax (VAT), which makes up the second-biggest share of tax revenue, also underperformed. This was because of the rapid rise in VAT refunds. The primary causes of this VAT refund increase are unclear. Some commentators attributed the rise in VAT refunds in 2022/23 to capital investment imports by business to deal with load shedding.

Lastly, it is important to note that a portion of the dip in revenue growth came from the Treasury’s decision to cut the corporate income tax rate last year. As predicted by those who opposed the tax reform, the rate cut led to decreased revenues without any gains in investment.

Figure 1: Government revenue since 2016/17. Note: 2023/24* are Budget projections; 2023/24** are IEJ estimates. (Source: National Treasury, various Budget Reviews, Annexure Table 2, own calculations)

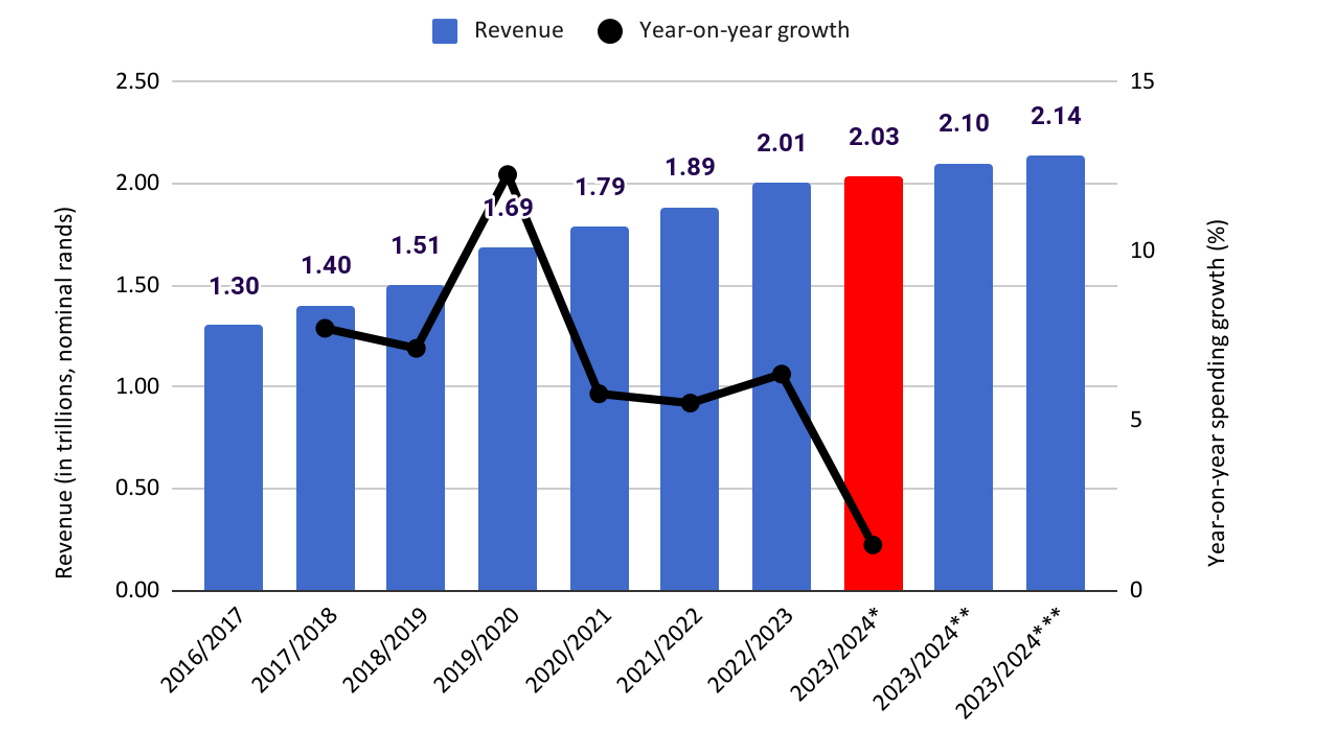

2 The government has spent more than it planned … because it failed to plan for necessary spending

The government will spend between R67.8-billion and R105.8-billion more than it budgeted for in 2023/24 (depending on which data period is used). To put this into perspective, the estimated minimum full-year overspend of R67.8-billion is half of what the government spent in May 2023 alone.

The government planned to increase spending by only 1.35% (not accounting for inflation) in 2023/24 (see Figure 2). This means that the real value of government spending would have decreased as inflation has averaged above 5% in 2023. Furthermore, if the population has grown by 1.8%, as it has for 2011-2022, it would mean the government planned to spend R32 221 per person in 2023/24, which would be a reduction compared to the roughly R32,364 it spent per person in 2022/23.

If, however, planned spending increased by 6.5% — the average rate it had been growing at since 2016/17 (excluding 2020/21) — then there would be no expenditure overrun, although the real value of government spending for every person would have still been below 2022/23 levels.

Thus, the real issue at hand is not the overrun — rather, planned spending was inadequate in the first place. Instead, there should be greater concern that the government prioritises the reduction of the deficit over giving adequate support to the population.

Figure 2: Government spending since 2016/17. Note: 2023/24* are Budget projections; 2023/24** are IEJ lower-bound estimates; 2023/24** are IEJ upper-bound estimates. (Source: National Treasury, various Budget Reviews, Annexure Table 2, own calculations)

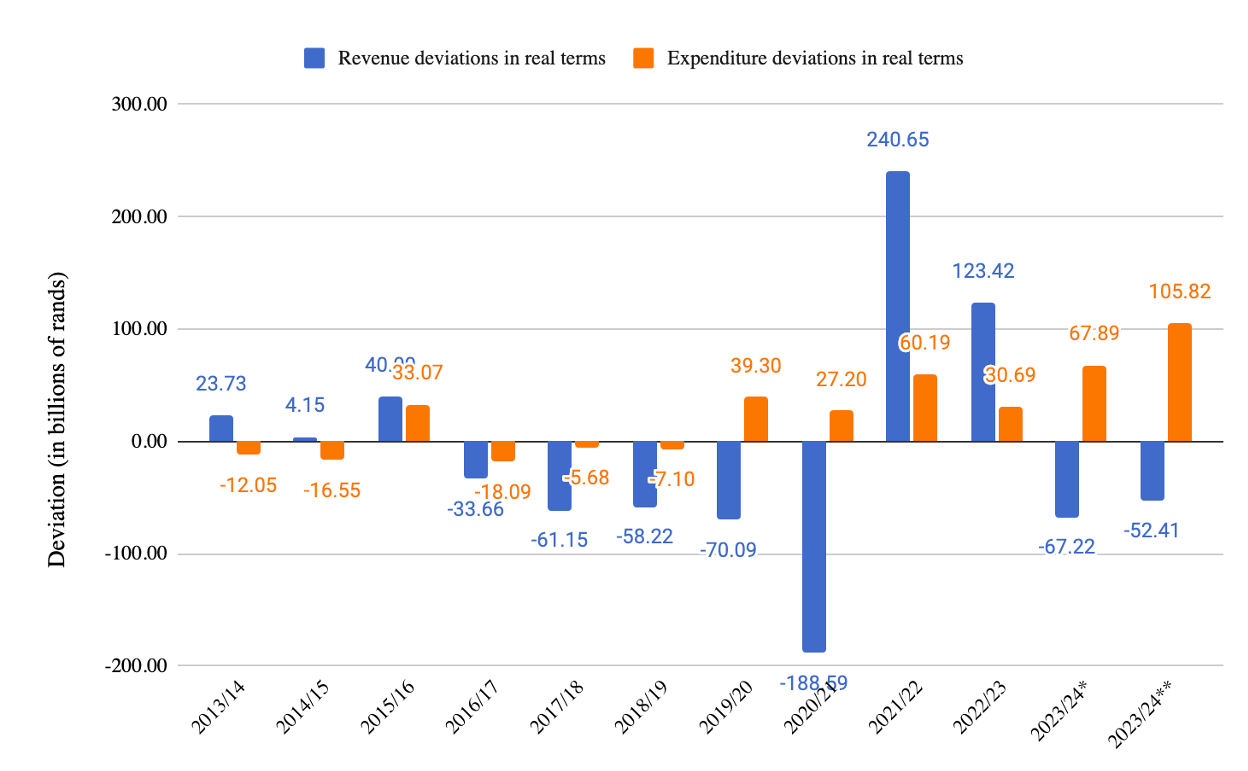

3 Our crisis is long-term and structural … but we are not in an unprecedented emergency

This moment has been branded as a “fiscal cliff” or “fiscal crisis”. This gives the impression that we are in an unprecedented emergency and need to take drastic immediate action to address it. But the fiscal picture is not unprecedented. The revenue shortfalls, of the scale that we project, have been the norm for South Africa. Figure 3 shows that in the years leading up to the Covid-19 pandemic, 2016/17 – 2019/20, revenue deviations (accounting for inflation) ranged from R33-billion to R70-billion.

The overspend, meanwhile, ranged from R27-billion to R60-billion in the 2019/20 – 2022/23 period. This is not to argue that missing budget targets is something we should welcome, but rather to dispel the notion that our situation now is unprecedented and requires an ill-considered knee-jerk response.

Further, the National Treasury’s plan to cut spending in response to anticipated shortfalls in 2016/17 was associated with even sharper shortfalls (in real terms) in the succeeding years. It is therefore concerning that National Treasury thinks further spending cuts will get us out of the purported “fiscal crisis”.

Figure 3: Deviations in revenue and expenditure. Note: 2023/24* are IEJ original estimates based on April-July data; 2023/24** are IEJ updated estimates based on April-August data. (Source: National Treasury, various Budget Reviews, Annexure Table 2, own calculations)

4 The budget mismatch was in part a political choice

The overspend is also a result of the National Treasury’s poor planning. The single largest part of the overspend is attributable to the supposedly higher-than-expected public sector wage settlement. The National Treasury had planned for only a 1.2% wage increase, despite inflation nearing 7% in 2022, whereas the final settlement came in at 7.5%. This added around R37.5-billion to government spending.

There have also been R26-billion of foreseeable but unaccommodated “unfunded budget submissions” relating to provincial health and education. It is unclear why essential social services, that the poor and marginalised rely on, were initially not adequately funded. It seems, then, that a substantial share of the expenditure overrun is a result of deliberate under-budgeting by the National Treasury.

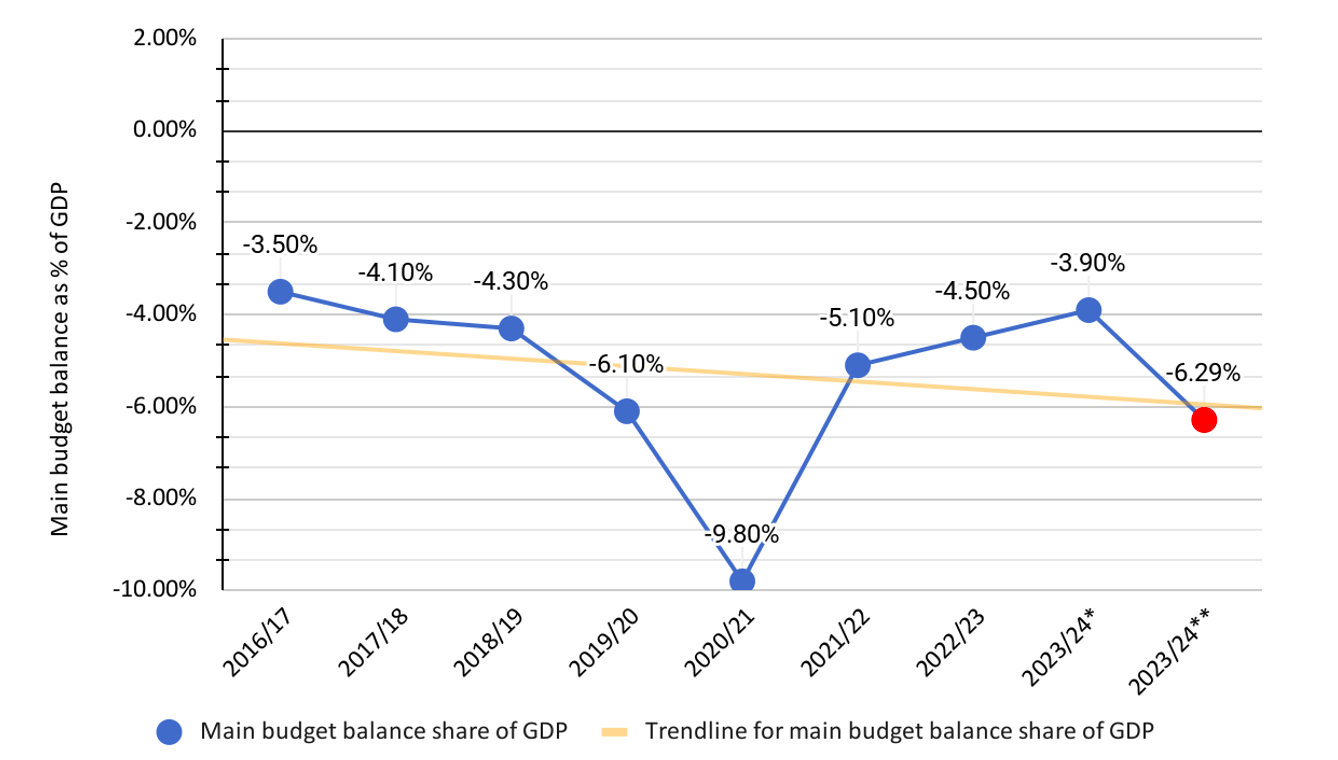

5 Our debt and deficit levels are not abnormally high

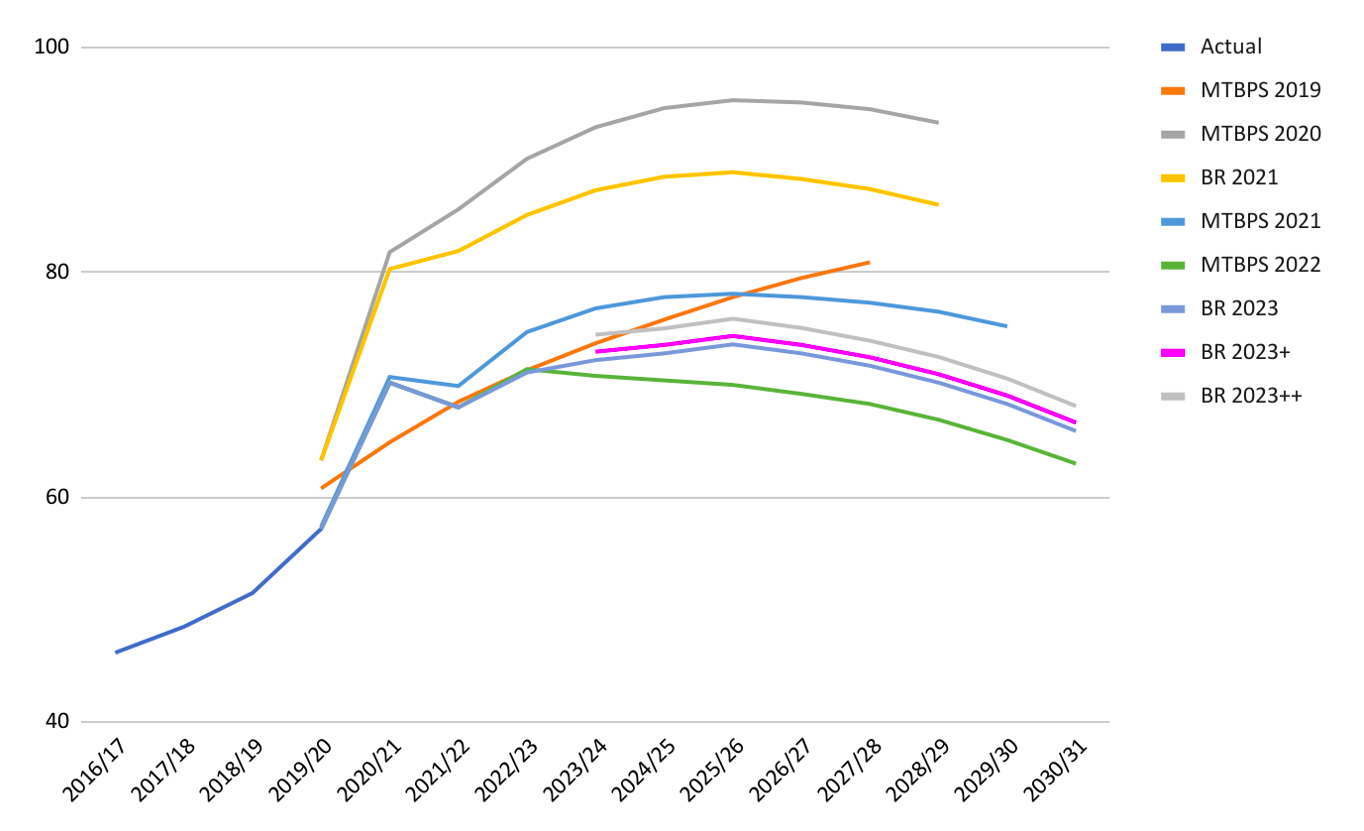

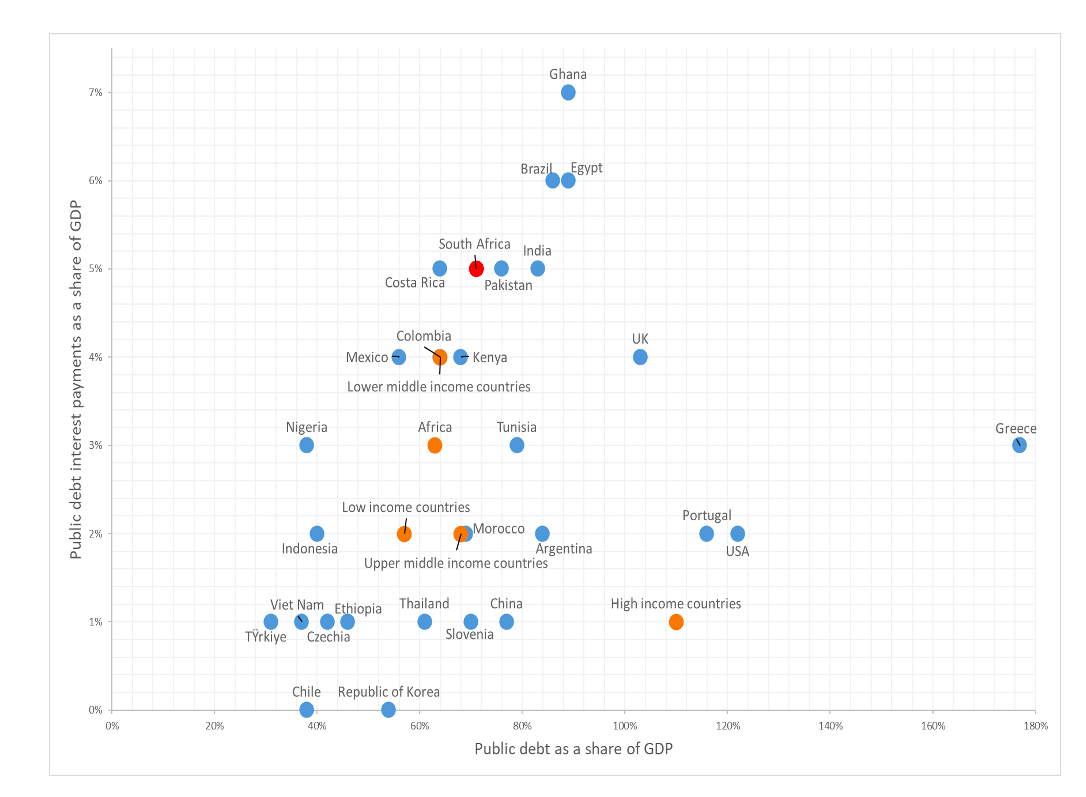

South Africa’s current debt levels are not at “crisis” proportions. South Africa’s debt-to-GDP ratio (at 71.4% in 2022/23) is in line with the emerging market and middle-income country average (of 69% in 2022/23). See Figure 7. However, if the government doesn’t support the economy to grow (by improving spending on social protection, services and employment-creating initiatives), our debt will become a big problem.

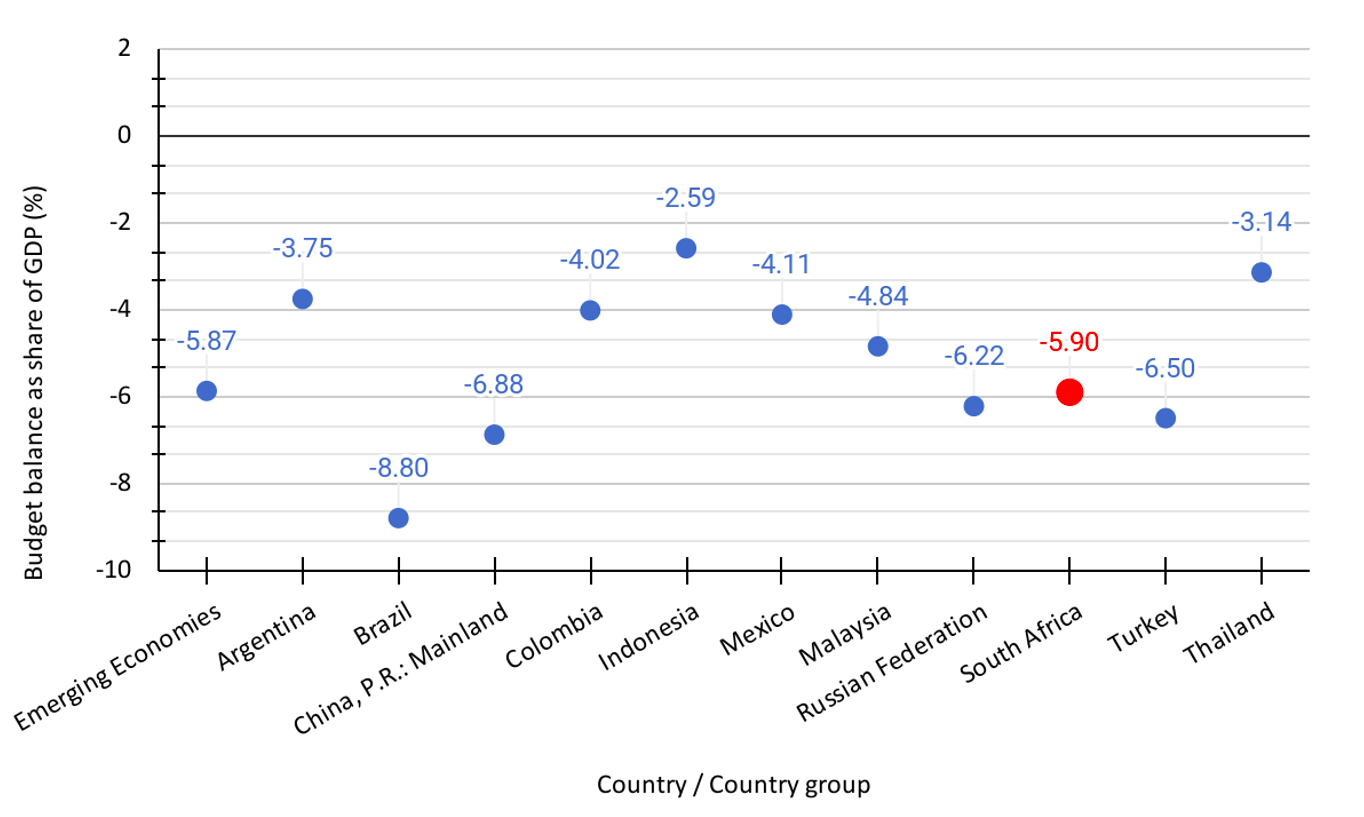

While we estimate the deficit may reach its highest level since 2020/21, at -6.29%, it is not extreme by any measure. Figure 4 shows that it is comparable to the deficit in 2019/20. South Africa’s deficit is also around the average of peer countries — as shown in Figure 5. The IMF estimates that South Africa’s 2023/24 deficit (as a share of GDP) will be -5.9%, which is only 0.03 percentage points greater than the average for all emerging economies.

Figure 4: Government budget deficits, 2016/17 – 2023/24. Note: 2023/24* National Budget expected deficit, 2023/24** IEJ estimated deficit. (Source: National Treasury, Budget Review 2023, Annexure Table 1)

Figure 5: Government deficit in major emerging economies, 2023. (Source: IMF Fiscal Monitor, 2023, own calculations)

Even if we made up for the entire revenue shortfall with borrowing, this would only increase the gross debt-to-GDP ratio by approximately one percentage point (BR 2023+ in Figure 6). If the full revenue shortfall and full projected expenditure overrun were covered by additional borrowing this would increase the gross debt-to-GDP ratio by approximately two percentage points (BR2023++ in Figure 6). In either case, the debt trajectory would still be considerably lower than that forecast in 2019, 2020, and 2021. The 2021 National Budget considered the stabilisation of debt at 88.9% in 2025/26 as “a sound platform for sustainable growth”.

Figure 6: Debt-to-GDP growth projections in different MTBPSs and National Budgets. (Source: National Treasury, various Budget Reviews and MTBPSs, own calculations)

6 The cost of debt is high and rising

While South Africa’s debt levels are not particularly high, the yearly cost of paying for this debt is relatively high when compared to peer countries. One can see in Figure 7, that South Africa’s position on the left-to-right x-axis shows that our debt-to-GDP ratio is similar to that of peer countries. However, on the top-to-bottom y-axis, the amount South Africa pays in interest payments (as a share of GDP) is unusually high.

Figure 7: Public debt and interest payments as a share of GDP for select countries, 2022. (Source: UNCTAD, 2023)

These high debt service costs are an outcome of the relatively high interest rates that the government pays on its debt. There are three driving factors for this.

First, investors are demanding higher returns for lending to the South African government as they feel that economic growth will continue to be low (in part due to inappropriate fiscal policy), which will weaken the government’s ability to pay back its debts.

The second is that since 2022, there has been a decline in the demand for financial assets (for example bonds and stocks) from emerging economies such as South Africa.

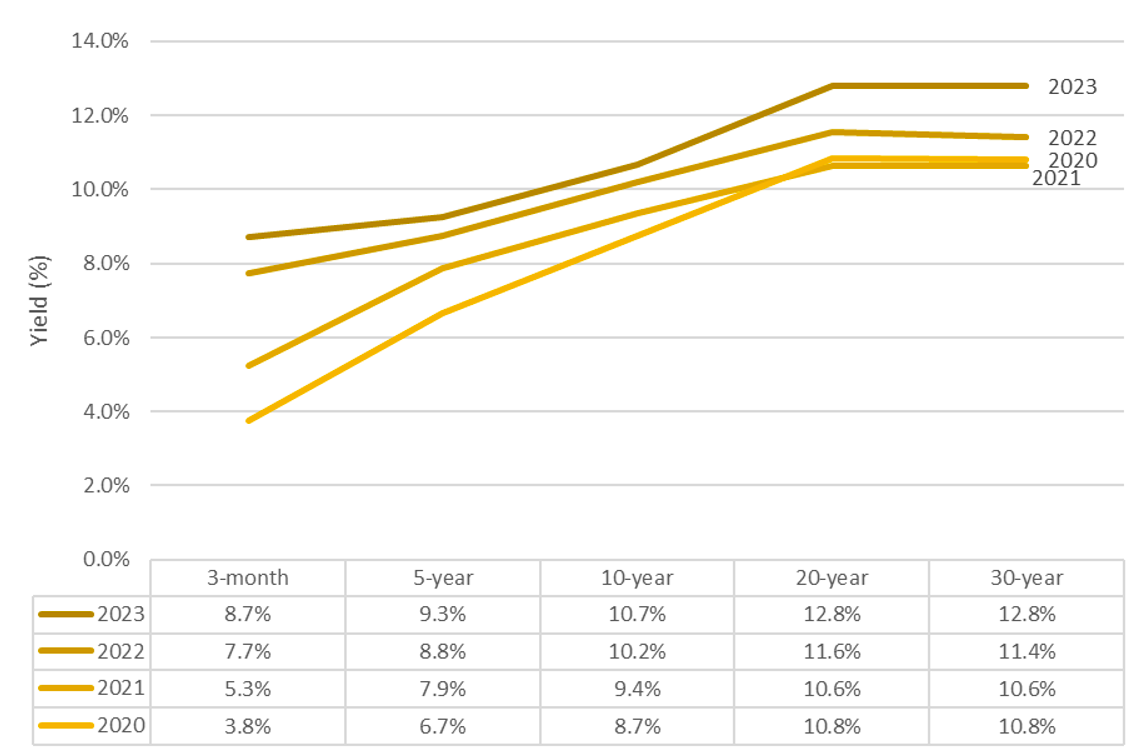

The third is that South Africa has an unusually large share of relatively more expensive, very long-term debt. The way in which debt has increased in recent years and the difference in cost between short- and long-term borrowing is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8: South African Yield Curve — interest rates associated with different bonds. (Source: World Government Bonds)

7 There is no short-term risk of a debt crisis … but cuts that hamper growth will increase the danger

Nearly 90% of outstanding government debt will have to be paid back over many years and can be paid back in rands. South Africa retains strong access to local and international bond markets and has substantial pools of domestic finance that can be drawn on.

However, other factors, such as poor economic performance, may make South African bonds unattractive to investors. Therefore, economic growth remains important for the government’s ability to pay back its debt. The low share of foreign currency-denominated debt means that the country is less exposed to exchange rate fluctuations, although these still do have an impact on the foreign currency portion of debt. Our debt profile therefore lowers our vulnerability to a debt crisis, especially in the short term.

However, as long as we do not have a state-supported growth strategy (and continued budget cuts), it will get harder and harder to service our debt. While we are not in immediate danger of a debt crisis, if we continue on an austerity path, we could “cut” our way into one.

8 The Treasury’s proposed cuts will make our long-term challenges worse … but the government has the tools to address them

Instead of rushed and indiscriminate budget cuts, we recommend that the government approaches the impending mismatch in a careful and considered way, that takes into account the long-term. Fiscal policy objectives should be defined in developmental terms:

- Spurring employment;

- Maintaining demand;

- Improving the productive capacity of the economy by expanding human and physical capital;

- Reducing inequality and poverty;

- Staving off destitution; and

- Building social cohesion.

Even when viewed more narrowly, the government has a choice of stabilising debt in a way that may benefit workers and the poor — through faster economic growth — or in a way that will have a negative impact on marginalised groups and the economy as a whole, through reducing spending.

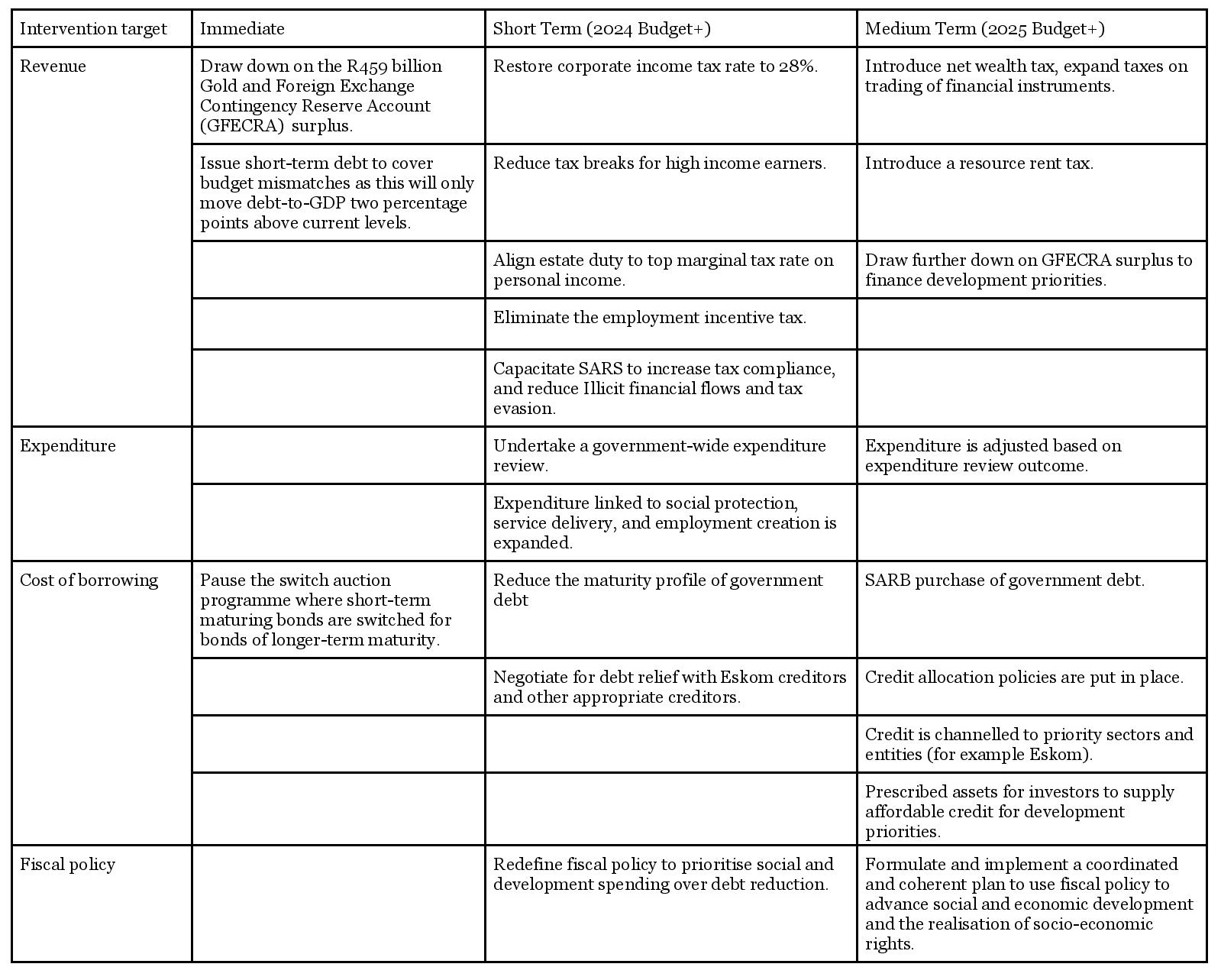

Below we have listed some of the measures that National Treasury and other organs of the government can take to address the issues we are facing. These recommendations are divided by the time frame and target.

DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

South Africa has been trying to spend it’s way out of trouble for years and it’s not working anymore because there are structural issues at play which the treasury has no control of such as crime, corruption, poor service delivery, contruction mafia, etc.

Trying to portray that South Africa is not in a financial and economic crisis and that it is in a similar position to it’s peers is like saying things are fine because we’re all on sinking ships.

CIT may have dropped a bit but isn’t that also largely due to corporates needing to spend billions on diesel due to load shedding and less to do with the fact that the tax rate was dropped a bit to try encourage investment and job growth? Where is that missing bit of analysis?

Then to top it off a bunch of wealth taxes are proposed to raise more money. We don’t have a money problem – we have a spending (theft/corruption) problem. Taxing the high net worth individuals more will just chase more of them away and we have relatively few who are helping prop up this failed state. There are roughly only 163 000 individuals earning over R1.5 million/annum and contibuting nearly 30% of all PIT (which is one of the biggest sources of tax income). Many of them are already leaving but increasing taxes will just accelerate the process.

We need to fix the faulty and leaking bucket first before any more money is poured into it.