BOOK REVIEW

Stephen Marais’ memoir raises questions and choices beyond his life in the Struggle and prison

Stephen Johannes Marais’ autobiography, ‘The true confessions of an unrehabilitated terrorist: Anecdotes and Antidotes’, raises not just questions arising from the Struggle, but a whole range of other issues that may touch on the lives of readers. This is done with searing honesty as he examines his life choices and the costs that ensue.

The genre of prison literature is now rather crowded with several books, having appeared since the 1960s. Most of these have been written by men. Exiled academic Elaine Unterhalter once wrote of these forming part of the literature of “heroic masculinity”.

It applies to a broader body of literature referring to men going off on a “journey” which is dangerous, leaving their lovers or wives behind, who have meals and other resources ready for their return.

The heroic masculine project tends to relate what the men do in an impersonal, repressed way. They tend not to express the fears or anguish they may have experienced.

Heroic masculinity tends to replicate the public/private dichotomy, with women at home to care for the house and children and the “real work” is done by men. Likewise, involvement in the Struggle is seen as “work”, and although feminism came to have a number of significant female and male standard bearers (like Chris Hani), the Struggle nevertheless tended to designate the places of men and women in a patriarchal manner.

In this respect, Stephen Marais’s book is very different and very self-reflective. It is very much about South Africa, the Struggle and the experience of political commitment. But it is also very much about Stephen and the different phases of his life. Anyone who reads the book will find not just questions arising from the Struggle, but a whole range of other issues that may touch on their own lives. This is done with searing honesty as he examines his life choices and the costs that ensue.

From harsh beginnings

The book is wide-ranging in the areas that were formative in Stephen’s life. He has lots of anecdotes that are funny, and others that are part of the harsh upbringing of many young boys in South Africa, white and black, with sadistic teachers and other experiences that are brought to the surface. In raising these, Stephen gives a voice to others who have not admitted to or are unable to express the harm done to them as children.

The book is funny, as when he reminisces about his Ouma who, when he tells her that Verwoerd had been killed, just says “Verwoerd en sy apartheid is ‘n klomp kak.” When he asks why his grandfather is always reading his bible, Ouma says he’s “cramming for his finals”.

In the course of his wanderings prior to joining MK, he evades the army, and lives in villages in Lesotho and the former Transkei. His life there is no different from that of the ordinary village people and he tries to learn whatever the language is that may be spoken in these areas. One quality that shines through his various visits to villages is his humility.

In some ways, Stephen is very eccentric. I’ve also written prison memoirs but did not write or have the capacity to write about some things that Stephen has covered, as with his conversations with birds who call him a hypocrite, and other phrases that he has to look up in his dictionary. That is not a criticism so much as us inhabiting different “head spaces”. Our preoccupations converge but also diverge radically. (When I made this point at a book launch, one former prisoner “exposed” me as also having had a bird in prison and “talking” to it).

One of the features of the book that may be unique is that it derives from a series of exchanges between himself and his Facebook friends who urged him to make what he was writing in postings into a book. Many of these exchanges are in the book with Stephen relating one or other story from his life or expressing his view on a topic and that resonates with his Facebook friends and evokes a debate.

Many of us would not have the patience to engage with so many people, but he does do so respectfully. Stephen has an endless capacity to engage with a variety of people. He takes them seriously. They take what he says seriously. And in some ways, these exchanges may have contributed to the well-being of these people.

They keep on asking: “Where’s the book? Where’s the book?”

Prison whispers

I first met Stephen in John Vorster Square in 1986. We were not really supposed to meet or talk. But somehow or other, as with most prisoners, we were able to have snatches of conversation in what used to be a very unpleasant environment, as he relates in the book.

I was there as a State of Emergency detainee. He was en route to being a sentenced political prisoner. I saw him again after I was moved to Johannesburg (Diepkloof) Prison still as a State of Emergency detainee. He was then an awaiting trial prisoner. We talked a bit illicitly, and he was able to smuggle a newspaper to me. Awaiting trial prisoners were allowed newspapers and State of Emergency detainees were generally not allowed at that point, though we got them later.

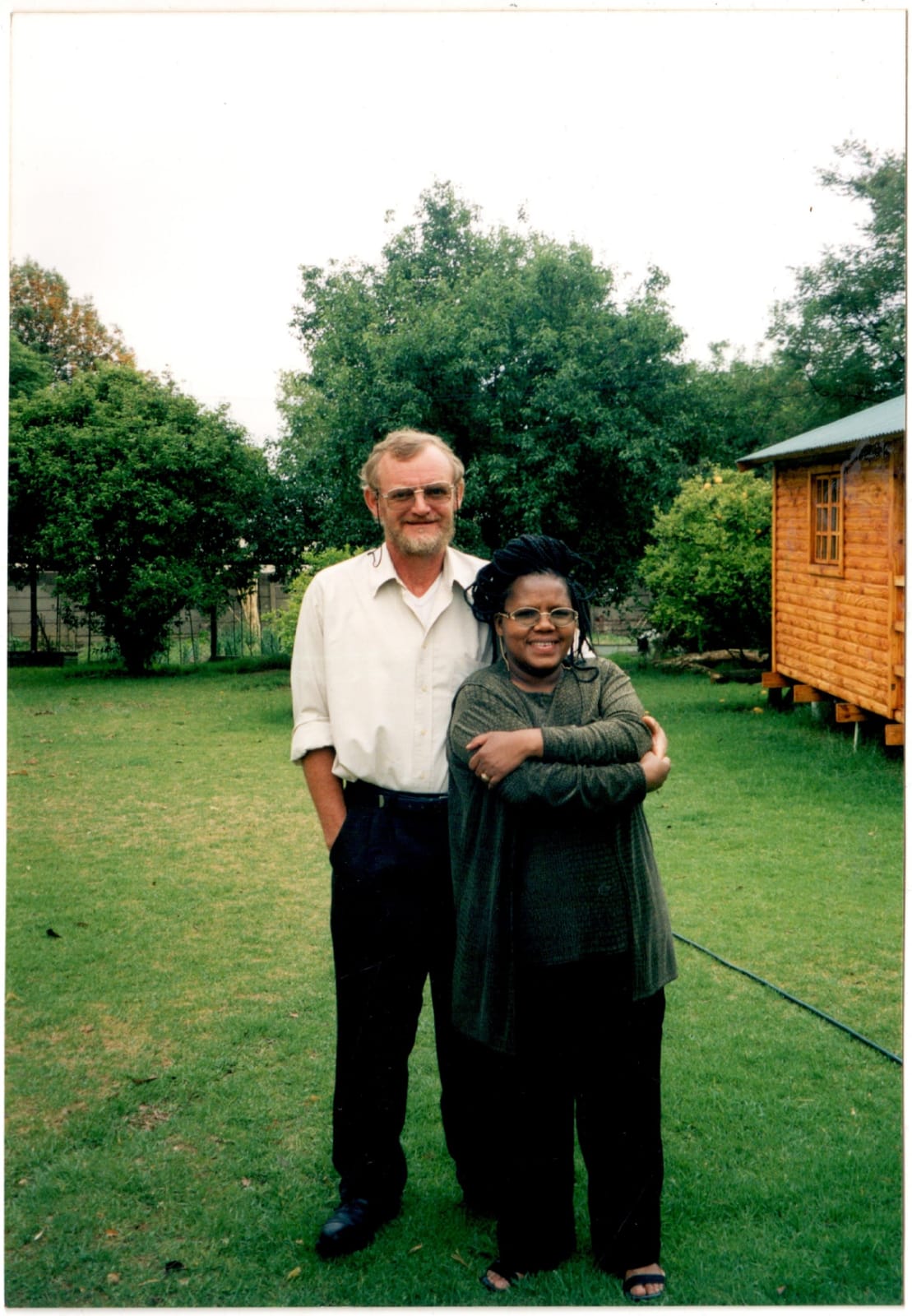

I remained in detention for another two years or so. When I came out of prison, Stephen was still inside. He records in the book that I went to see him when he came out, after he spent four-and-a-half years inside. I didn’t know then that there was a romance between him and Khethiwe, known to me as Kate Mboweni. I knew Kate from the UDF days when she was active in the Northern Transvaal region. She is now his wife and mother to their sons.

Stephen Marais and his wife Kate. (Photo: Supplied)

Health battles

Although we got on fine, I didn’t see much of him after that. About a year or so back I heard that he had had one lung removed because of cancer and also a brain tumour. It has been quite intense since then. I found out where he stayed in Lombardy East, which turned out to be very close to where I now stay. I started to visit regularly and I met Khethiwe again, and their two sons Mlungisi and Nkululeko, who together with Khethiwe take on the caregiving with a good spirit, no complaining and generally smiling, though Stephen sometimes irritates them, especially when he does not eat.

I didn’t really know Stephen before visiting him in Lombardy East. After a while he was readmitted to hospital. And he seemed at one stage to be coming very close to losing the battle. I remember seeing him then and afterwards saying, “so you saw the other side. But you decided to come back.” I was making a rather weak joke.

However, in the book, paradoxically, he records how during his younger days he experimented with drugs and went to “heaven” and to “hell” and relates to the readers what that was like.

Refusing to break

One gets the impression that Stephen understood (like many of us) that he would one day be a political prisoner and could face the ordeal of being interrogated. And before that happens, he travels all over southern Africa to avoid being drafted into the military.

When Stephen was in detention, he says that he “broke”. Everyone who is detained fears that they will betray the Struggle by “breaking”.

We need to understand that almost every one of us who goes into detention, whether or not we are tortured, end up doing some things because of the conditions under which we are held, doing or saying some things that we would rather not do or say. But we sometimes speak about those matters in order to safeguard other more important things.

It is interesting that before he goes in for the interrogation where he says he “broke”, an African security policeman says to him, “they really want to break you now. So just decide on the one or two things that you really don’t want to tell them and just make sure you don’t.” It’s very interesting that in the belly of the beast, you do have some people who are cooperating — in unexpected ways — with the resistance to the apartheid regime. This is, of course, limited by the conditions.

What one learns from Stephen’s detention is not that he “broke”, but that he retained his subjective powers as a human being and did not lose all power to the interrogators, that he did decide to withhold certain things and gave them other information which he may not have given in other situations, but withheld the most important information.

It’s very important to understand that in all difficult situations, one can decide whether one allows one’s captors or those more powerful in a variety of ways to reify one, meaning to treat a person like a thing. Then one can be battered and lose all agency or subjective capacity. And Stephen did not lose that. DM

This article first appeared on Creamer Media’s polity.org.za

The book is obtainable from the author for R200. SMS or WhatsApp 072 244 3599. It can be sent to the nearest Postnet for an extra R109 or Pep Stores for R100. Six can be delivered for the same delivery price or if one lives in the Johannesburg area can be collected from the author’s home. Deposits to be made into account of Stephen J Marais. Bank: Standard. Account number: 678381615. Please use name and surname as reference. The book is also on sale at Love Books in Melville.

Raymond Suttner is a former political prisoner, whose prison experiences are recorded in Inside Apartheid’s Prison (Jacana, 2 ed, 2017).

Can’t wait to read the book.