THEATRE

Striking the right tone — Booker Prize-winning novel ‘The Promise’ reimagined for stage

Veteran theatre-maker Sylvaine Strike has collaborated with Damon Galgut to bring his vision to theatre-goers.

In the slightly unsanctified church hall somewhere in District Six, actors in sweatpants and takkies (and one wearing a pair of Crocs clogs — with socks!) were sprawled on the floor in a vague semi-circle. Some sat upright like ballerinas, some hunched over their scripts, some lay flat on their stomachs, a couple even had chairs under their bums.

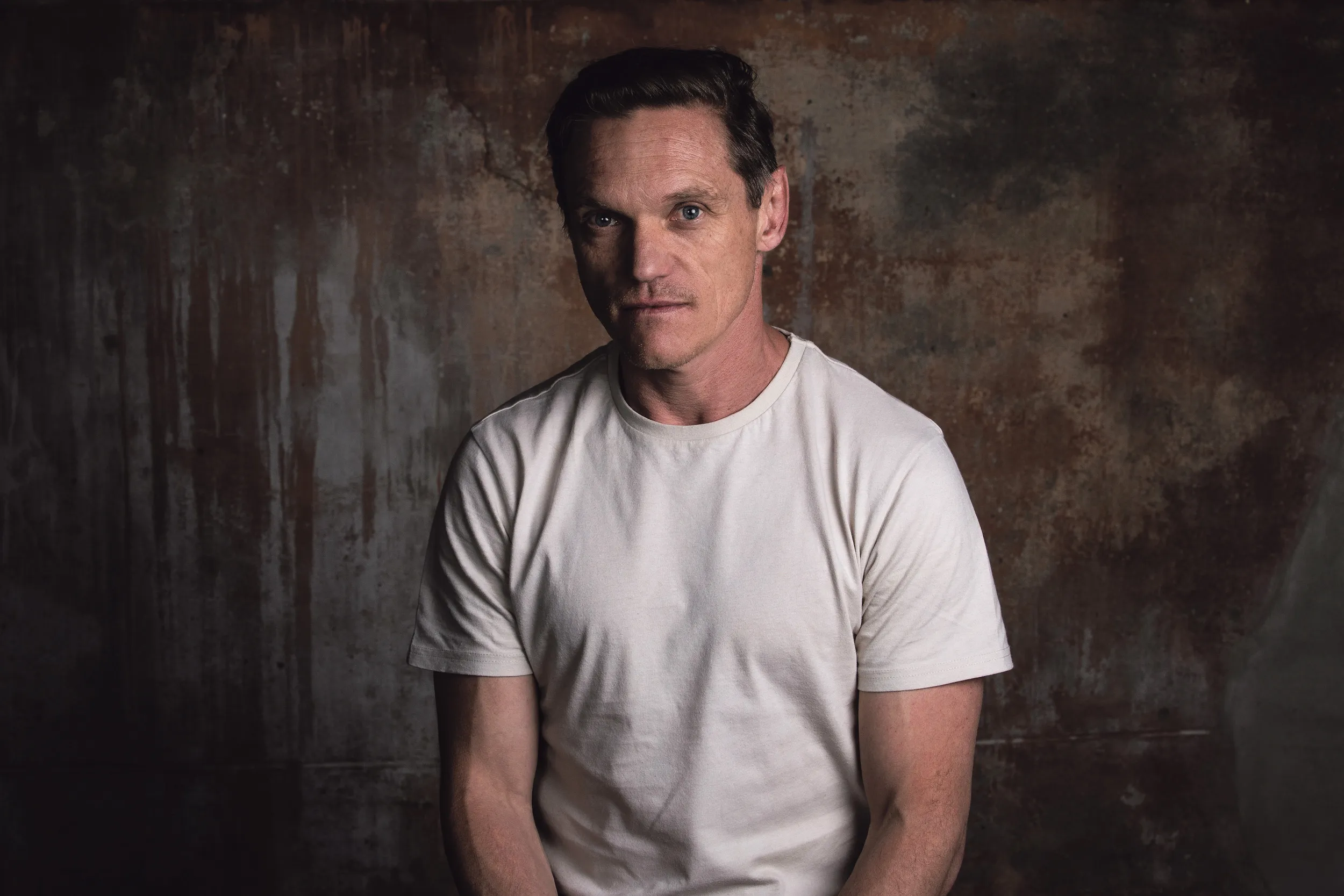

At one point, the mercurial actor-comedian Rob van Vuuren rolled onto his back, perhaps pretending to be a cockroach. It was hard to know if this was in character or if he was stretching, or if he was going with an impulse in search of some new physical action he’d later take into performance.

Despite the unceremonious setting and the pervading atmosphere of casual chaos, sparks of creative energy blazed about the room, igniting the space between the actors as words were brought to life, bits of dialogue acquiring some vital force as they were uttered, repeated at a different rhythm, said with a different intention.

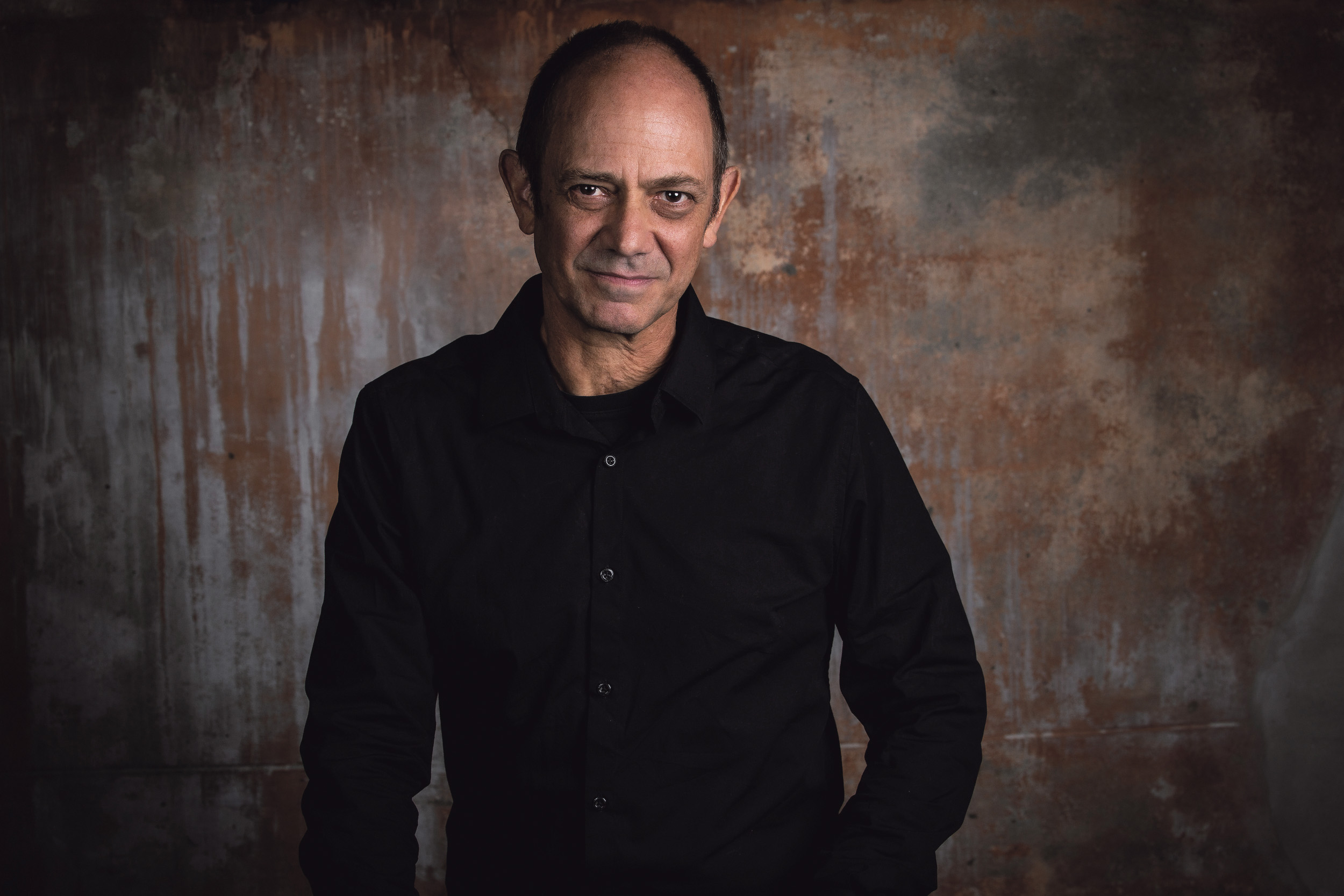

Sylvaine Strike. (Photo: Martin Kluge)

Overseeing this mysterious process, director Sylvaine Strike leaned forward in her chair, gently gave notes and suggestions, wondered out loud about some deeper nuance she wanted her actors to explore.

It was midway into a Friday morning read-through of the fourth and final act of The Promise, most likely the year’s most anticipated South African theatre opening, perhaps the most important in years.

Based on the eponymous 2021 Booker Prize-winning novel, the script has been adapted by the book’s author, Damon Galgut, who has collaborated closely with Strike to tease out new dimensions for his story about the decline of “a typical bunch of white South Africans” who hail from a small farm outside Pretoria.

Read more in Daily Maverick: On white lies and hope for salvation: ‘The Promise’ by Damon Galgut

Read-through complete, the cast transferred themselves from the floor to the set. A vast wooden structure that occupied half the hall, it seemed like a character in its own right. For the next hour or so, a multitude of scenes unfolded before me: Van Vuuren vividly miming getting sloshed at a bar; two comically vile women conspiring; a ridiculously funny charlatan-guru sermonising at a funeral; a slimy property lawyer squelching across the stage; a satire of preposterous lust that culminated with two actors literally humping their way across the set and over the edge, landing on the floor in a postcoital heap; and, finally, in the bosom of a tiny house, an emotional exchange that felt so saturated with the awfulness of South Africa’s social imbalances that I felt tears running down my cheeks.

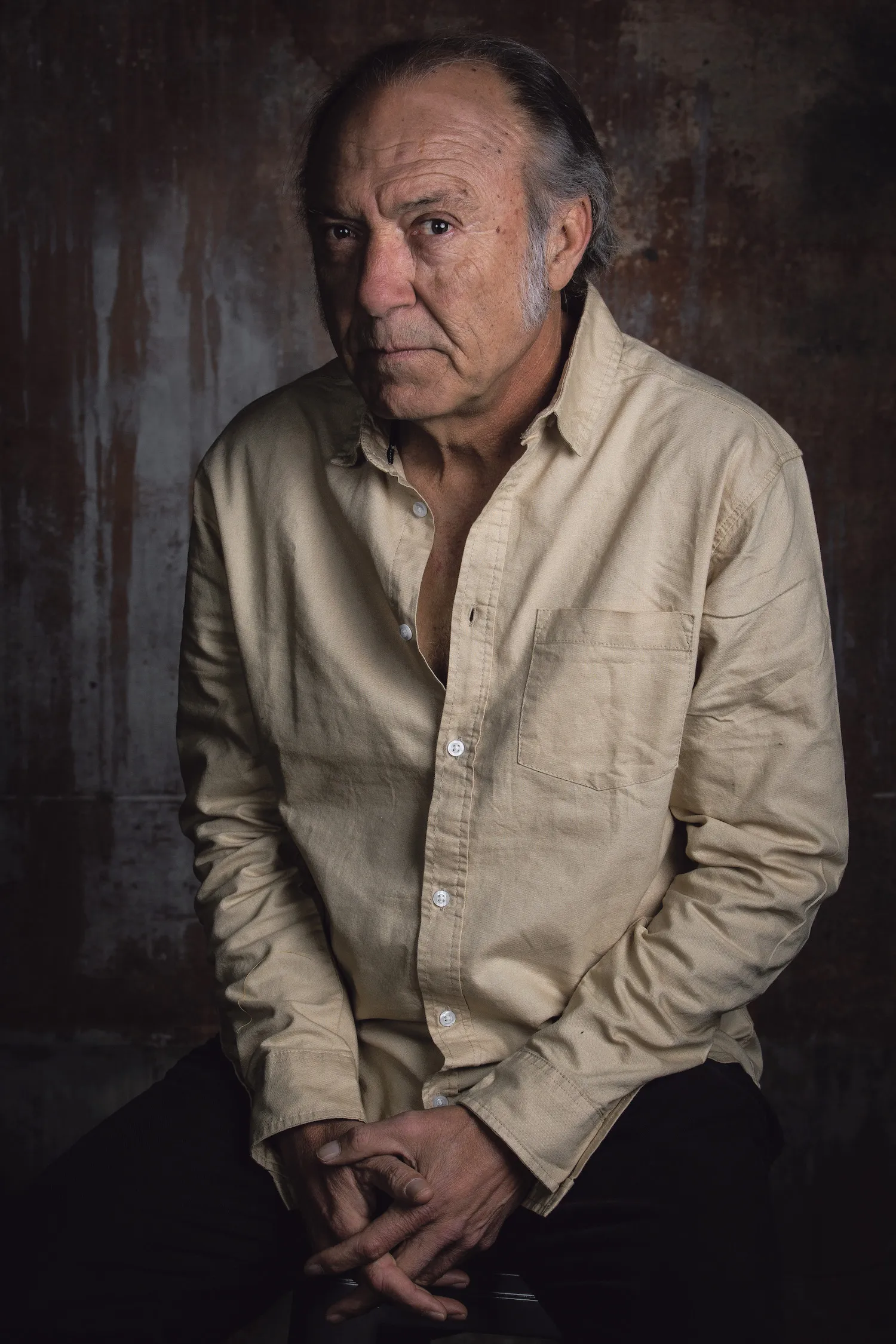

Damon Galgut. (Photo: Martin Kluge)

When the cast finally broke for lunch, Strike and I slipped into a dusty side room to talk about the process that was unfolding. She and her team were into the final two weeks of rehearsal and, in the adjacent room, Galgut was diligently working with the assistant director to shave off more of his words to get the play’s running time down.

“He’s so unprecious about his own work,” Strike said. “He should be sick of the novel by now. He’s toured the world with it, attended press junket after press junket. And yet he’s been so generous with his time, has attended most rehearsals, and has been genuinely moved by what I’m doing with his work. He often cries in the rehearsal. It means something’s working.”

Strike has been working on this project for 16 months — first a series of one-on-one meetings with Galgut, and then the development of a unique language that would inform his script, a document that has evolved over a number of increasingly shorter drafts.

Jane de Wet plays Amor Swart. (Photo: Martin Kluge)

“It’s been the longest preproduction period of my life,” she said, admitting to feeling the pressure of overseeing a process whose outcome will undoubtedly attract considerable scrutiny. Much of the pressure, she said, is the daunting weight of the novel itself, the esteem in which she and the cast hold it, their desire to do it justice.

The book had felt incredibly personal to Strike who, like Galgut, grew up in Pretoria, a place she believes the novel captures perfectly. “The way he tapped into the colours, the sounds and the smells and the way it felt like to be a child during that time.”

Strike says she grew up in an area called Verwoerdburg (now Centurion) where, at the local library, there were bronzes of the apartheid architect’s shoes and hat, and photos of him with his Alsatians. As a little girl, still too young to understand the politics, her French mother would simply tell her that this shrine was to a “very, very bad man”, and that one day she would explain why.

Cintaine Schutte and Albert Pretorius play Tannie Marina and Dominee Simmers. (Photo: Martin Kluge)

“Knowing something was terribly wrong, but not knowing what it was — that’s what the novel captured for me, being there at that particular time, in a suburban space vastly separated from reality. It captured that spirit of Pretoria, something dull and deceitful. And also the damage from being lied to. The consequences of that.”

Strike says she was drawn to the novel because it made her feel seen, understood and included.

Somewhat fortuitously, some 30-odd years ago Galgut had been among Strike’s university lecturers — one semester of text analysis at the University of Cape Town’s drama school. And whereas she has long been an avid reader of his books, he has — over the years and unbeknown to Strike — been “a great fan” of her theatre work.

From her treatment of productions such as Endgame and Curse of the Starving Class, particularly her manner of “drawing on the poetry of the performer’s body as primary storyteller”, he thought she’d be a good match (“the perfect director” for The Promise, he says) and he approached her to collaborate with him.

She agreed on condition that he would adapt alongside her, “because I didn’t feel like I could tinker with his words”.

The problem with adaptations is that they invite comparisons, often unfair ones since there are two very different and distinct mediums being assessed alongside each other. Apart from the challenge of doing justice to the original material, the play will most likely be judged for its ability to transcend the novel, to bring new insights to a story that many readers might prefer to keep as something personal and precious.

Kate Normington plays Rachel Swart (and numerous other characters). (Photo: Martin Kluge)

“I think there’s a part of Damon that’s curious to find out what can be said in a way that the novel couldn’t say,” Strike said. She too has a more than peripheral interest in the relationship between works in different mediums: while working on The Promise, she has been simultaneously reading for an MA, looking at the question of adaptation and specifically at the notion of the alchemy of bringing stories to the stage, making the words and ideas visible in a shared space. Her conception is that theatre is a form of ritual communion, a place where collective healing can happen.

Strike’s vision was for the play to be “heavily built on the language of physicality” as well as on “a language of props not necessarily being important, where some things could be mimed, while other things are more concrete”. She was inspired by the novel’s roaming camera technique, which — in translation from page to stage — made complete sense in her imagination. “In my brain, there were transitions that could work very easily without needing to shift to different locations.”

In her brief to set designer Josh Lindberg this sense of a fluid environment was expressed as a request for him to create a “morphable” world. “I wanted a sense of having one item that unfolds from another — I saw a door transforming into a coffin, into the mortuary table, into a dinner table. A single door symbolising the entrance of a home. I also wanted him to work with the theme of origami and the theme of sinking, tipping, sliding.”

The resulting set is a visual stunner full of slopes and ramps and drop-offs, strewn with sawn-off chairs that seem to be disappearing, doors off their hinges, wooden frames and upside-down benches. It’s an expressionistic, abstract environment, instantly denoting an off-kilter, shaky land.

Frank Opperman plays Manie Swart (and other characters). (Photo: Martin Kluge)

Another thing with which Strike connected strongly in the novel is its use of magical realism. “That idea that the dead mom is around, that the departed dad’s around, that these characters creep into the story, comment on it.”

The book’s magical realism has informed the way the cast will inhabit the space, while “off stage” the actors congregate at the edges of the set — like a ghostly chorus — where they interject with whispers and synchronised breath, sound effects, bird noises and singing, provide additional atmosphere and insert layers of meaning, in the way words on the page add dimension to what is conjured in our imaginations when reading. All these live human sounds will be further enhanced by Charl-Johan Lingenfelder’s rich soundscape of instrumentation, recordings and music.

“I also love the essence of the narrator being fluid,” said Strike. “Of having the ‘camera’ roaming with him. Of him commenting on his own work. Of him changing his mind, saying things like ‘We’re here!’, and then, ‘Well, actually, maybe if you come this way, we’ll go there instead.’”

Giving physical dimension to this narrating voice, actor Chuma Sopotela plays a literalised Narrator who reads breathily from the pages of the book, skips sections, jumps ahead, rewinds, omits undesirable bits, becomes a living commentary on the way the story is told as she figuratively holds our country’s unfolding narrative in her hands.

Apart from her role as the Narrator, Sopotela plays Salome, the Sotho woman who readers will recall is disconcertingly silent in the novel, despite being the character around whom the narrative spins, and for whom the broken promise of a small piece of land signifies something of all the rot and evil that’s stacked against our nation.

Chuma Sopotela and Sanda Shandu play Salome and her son Lukas. Sopotela also takes on the role of the Narrator. (Photo: Martin Kluge)

“Many people, particularly non-South Africans, responded to the character of Salome by saying she’s too silent, that there’s no black woman’s voice in the novel.” Strike is interested to see if, by giving physical presence to this black woman whose silence pervades the novel, the play can have the effect of making “Salome’s invisibility hyper-visible and hyper-palpable”.

This is the kind of alchemy she is interested in — in this case, theatre’s capacity to transform silence into its opposite, to turn a thing that is essentially invisible into something that can be witnessed and felt.

Rob van Vuuren plays Anton Swart. (Photo: Martin Kluge)

For Strike, that’s where the magic and healing happen — in those moments when an audience collectively recognises our shared humanity. “And maybe the live experience of seeing us tell this story will have a galvanising effect of recognising ourselves as South Africans. Not in an Athol Fugard way, but in a way of posing the questions: ‘How do we write this story going forward?’, ‘What do we do to ensure our humanity remains intact?’ and ‘How do we wake up to the fact that, as white people, we have everything, while people like Salome continue to have nothing?’ And perhaps for theatre-goers, there’ll be a shift, irrespective of whether they’ve read the novel or not.” DM

The Promise is in Cape Town’s Homecoming Centre (formerly the Fugard Theatre) until 6 October, then in Joburg’s The Market Theatre from 18 October to 5 November. Tickets from Webtickets.

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper, which is available countrywide for R29.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.