MATTERS OF OBSESSION

Serving a greater purpose: Sylvaine Strike and the human collective

With the hard-hit theatre sector steadily reopening, Sylvaine Strike directs Kiss of the Spider Woman, a play about human connection that taps into the prevailing zeitgeist – humanity’s craving for collective experience.

“We are an essential service to the soul,” says award-winning Johannesburg-based theatre director Sylvaine Strike. “Theatre is indispensable to the soul, but we live in a country where – in the grand scheme of things – the arts are not valued, artists are not valued, and where this essential service we offer is hardly ever acknowledged.”

Strike, who was awarded the Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres (Knight in the Order of Arts and Letters) by the French ministry of culture in 2019, says there is something “insanely disjointed” about how the performing arts have been targeted, ignored, dealt a devastating blow during the pandemic. “The imposition on theatres is mental and completely disproportionate… as if there’s some sort of awful punitive measure being taken against us.”

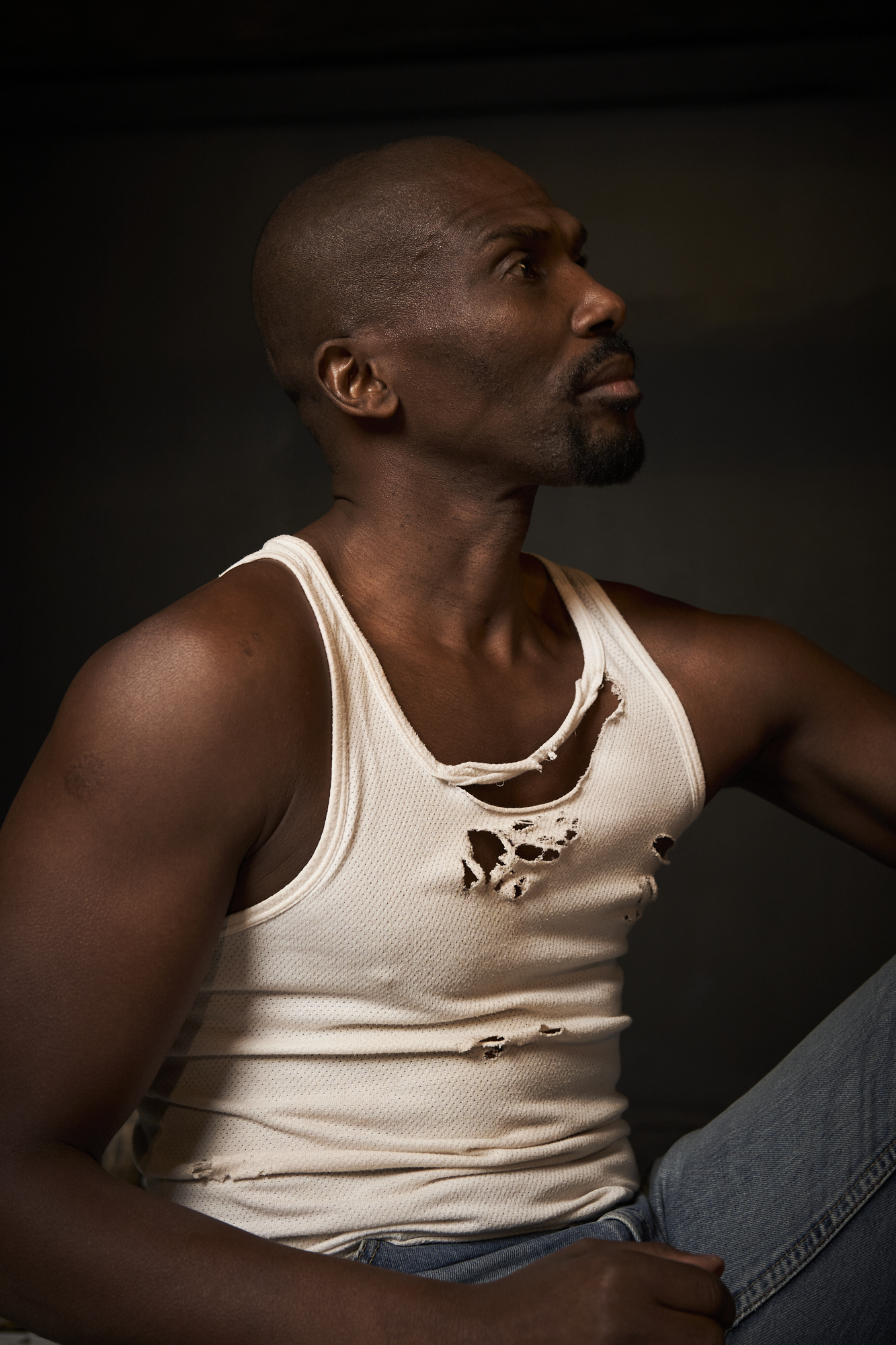

Sylvaine Strike performing in ‘Black and Blue’ in 2014. Photo by Val Adamson

As we talk during her lunch break between rehearsals at UCT’s Baxter Theatre, she cites the madness of flying to Cape Town “in an absolutely packed aeroplane” aware that she was coming to rehearse a show that’s required to play to a half-empty auditorium. It’s the first play she’s directed since lockdown began, and while she’s immensely grateful for the privilege, in her voice what’s evident is tremendous sadness because of the manner in which the ban on gatherings has effectively decimated an already fragile theatre industry.

And while a half-full theatre is considerably better than no theatre at all, it remains “incredibly hard in terms of ticket sales that need to sustain technicians, cleaners, ushers… never mind actors’ salaries, never mind all the other people who make theatre happen.”

She says there’s something inherently wrong with a country that refuses to see the value that theatre brings to people. “It’s indicative of a sick country that artists are made to feel like they don’t matter.”

The show Strike is directing for the Baxter is Kiss of the Spider Woman. She says that as the theatre sector starts to open up, many industry people will be living vicariously through it, keen to see it reignite theatre-going, administering to humanity’s inherent need for collective experience.

Wessel Pretorius and Mbulelo Grootboom in Kiss of the Spider Woman. Photo by Oscar O_Ryan

The Baxter, in fact, is mounting two important productions this month; the other is Lara Foot’s Life & Times of Michael K, a collaboration with Handspring Puppet Theatre adapted from JM Coetzee’s Booker Prize-winning novel. “I hope these two shows will give hope to the industry, be forerunners that start to rebuild confidence in the sector,” says Strike. “We’ve been in a state of deprivation for so long.”

The play, based on Argentine writer Manuel Puig’s 1976 novel, was first adapted for the stage in the 1980s and then as a film starring William Hurt and the late Raul Julia. It is set in a prison where two seemingly very different men are confined. What they – one an effete homosexual, the other a revolutionary – discover, is their shared humanity. It’s a tender, loving glimpse at our human compulsion to connect.

Wessel Pretorius in Kiss of the Spider Woman. Photo by Oscar O’ Ryan

Mbulelo Grootboom in Kiss of the Spider Woman. Photo by Oscar O’Ryan

The choice to do a play set in a prison has nothing to do with humanity’s recent experience of lockdowns and quarantines, Strike says, even if that does seem uncannily apt. Its theme of looking for connection during prolonged confinement certainly strikes a chord with our present moment, however.

“It’s about learning about the other,” Strike says. “And about accepting what you hate the most about yourself, because the other has made it beautiful for you. So you walk away with a sense that without the other we are nothing.”

Strike says it’s been emotional returning to the rehearsal room. “It’s been enormous for me. Enormous, I sense, for the actors as well. I’m acutely aware that we’re all in quite a fragile state. So much hangs in the balance. Whether or not theatres will stay open long enough for us to open this show. With talk of the third wave, we are wondering if we’ll rehearse till the end, and if we do open, if we’ll be closed before the end of our run.”

Strike says she’s also been acutely aware of the impact that the lack of performance opportunities over the last year-and-a-bit has had on her actors. That prolonged period of isolation and disconnection has seeped somewhat into their DNA.

“Something that’s quintessential to a performer’s survival and mental health is being visible,” she says. There’s a need to be seen, to have an audience to connect with.

“For performers, a lack of work equals a lack of visibility, which equals a kind of death. While we all have private lives, of course, professionally we only exist because others can see us – being seen is by definition what we do.”

Strike believes that the pandemic has made it startlingly evident that we live in a country where performers are not seen. “Or where what we do is seen as a luxury.” It means that their essential role in tending to the soul has been overlooked, negated.

Artists, she says, have “been made to feel dispensable”. To some extent it’s a result of the easy availability of quick-fix experiences. When we want a story, we just flick to Netflix, or turn on the radio. Children, instead of being taught to value theatre have been allowed to become dependent on their devices for stimulation. “Their passivity, as a consequence, is devastating.”

The theatre Strike sets out to create is anything but passive. Her goal is total engagement, to grip the audience in a moment of sustained ritual so that they are transformed. A kind of sacred alchemy is achieved “by altering an audience’s mood, their emotive space, their endorphins”.

And, she says, this alchemy is affected by the connection that happens between the audience and the actors who become, effectively, shamanic instruments of healing.

Unlike passively watching Netflix, “which demands little imagination because the story has been cut and edited for you,” a theatre audience must actively “participate in the suspension of disbelief”.

In this way the audience becomes part of something transcendental – it’s then, Strike believes, that collective healing can happen. It’s in that “suspended, non-binary, elevated space” she sets out to create on stage that the performance becomes a ritual that can shift consciousness.

It’s in order to achieve that shift in consciousness that Strike and her actors have rehearsed for four weeks. The process has involved discovering not only the timeless essence of the text, but distilling the energies and emotions of the actors’ real-world experiences so that those, too, will have become concentrated in the two characters – Valentin and Molina – who have been in prison for four years, confined together and effectively forced to connect. In this way, what audiences will experience is a microcosm of life that exists in a liminal space.

Getting to that space has been complicated by the process of rehearsing during a pandemic, though.

“Touch and connection are normally taken totally for granted,” Strike says. “As actors, we sweat on each other, spit on each other… that is the nature of performance. But during this particular process we began with masks on, and then started taking them off. And then there’s, ‘May I touch you? May I do this, may I do that?’ There’s been a very different energy, one that’s not necessarily wanted. But it has crept into our DNA, has crept into our fear of making someone else sick.”

There is a moment of intimacy in the show that’s quite pivotal to the narrative, that requires physical closeness between the actors, Strike explains. “But, of course, for the first half of the process we weren’t able to rehearse that moment because of Covid protocols. Because we hadn’t been in the same room together for 14 days.”

And so, unavoidably, that tentativeness with which human connection happens nowadays has become woven into the fabric of the performance. And Strike says it will necessarily become part of the meaning of the ritual, something that audiences will undoubtedly respond to, feel a familiarity with.

That need to connect with others is also at the heart of Strike’s directing process, and so she’s been aware of needing to modify how she works. “Usually I’m incredibly hands-on with my actors. It’s been really hard for me having to hold back. I was the one catching an aeroplane to come down to Cape Town, and there’s a worry I might expose them.”

She says that part of the great joy of working with actors is experiencing proximity with them, of being part of their process of transformation. It’s a form of alchemy that Strike gets to experience, something which “if there’s a pandemic,” she can’t get. She describes the absence of this proximity to actors as something akin to being denied access to loved ones, being unable to connect with a lover or with one’s children.

Strike says she was surprised by “how dark things could get, how dark things could feel” when she was unable to do what she loves, unable to experience that alchemy with actors and audiences.

On a practical level, for the sake of survival, the pandemic saw her stepping into her performer’s shoes, something she hadn’t done in a long time. “What surprised me about myself is how my survival instincts kicked in. I auditioned for Budget Insurance commercials. I started doing things that I’ve had the privilege of not needing to do because my career in theatre is established enough that I’ve been able to survive off making three plays a year.

“But I really didn’t care if people saw me in an insurance commercial. Because doing that advert meant I could put my kids through school. That surprised me about myself.”

Strike says while she’s been personally humbled by the economic realities wrought by the pandemic, she’s also been deeply aware of its devastating impact on the wider theatre community.

“We tend to think of actors as these people who are eternally able to fend for themselves – as if they don’t have families and children to put through school, feed and clothe. We don’t seem to form part of normal society, and yet we have the same bills and taxes.

“I know many people who are simply not coping. From putting food on the table to paying medical bills and coping with mental health issues. Because their survival relies on getting as many singing gigs as possible. Or getting an acting contract. Or going from one musical to the next. That’s how they pay their rent. From a very basic perspective, their survival is reliant on having audiences.

“I think that this pandemic has activated the arts sector, and revealed the flaws of who is leading us – who the minister overseeing the arts is. What’s evident is that there is absolutely no knowledge of what we do, no knowledge of how freelancers actually survive. The fact that we live from job to job is inconceivable to most people, but it is how we’ve done it for hundreds of years. The nature of the live performer is that we do gigs. But we have a government that doesn’t understand, value or revere our profession.”

And yet Strike says she believes firmly in her heart that theatre will not die. “Theatre will survive. It has survived wars, it’s survived other pandemics. There is no chance of it not surviving.”

She says it is the artists – those performers who, in order to exist, need to be seen – who will ensure it survives. Because they must. Because it is in their blood, part of their DNA.

“And so we will make it work. Whether it’s performing in a flipping parking lot, or we do it in a park or under a tree, or in an outdoor arena like it used to be in ancient Greece… We will make it work, because the human need for storytelling will endure.” DM/ML

Kiss of the Spider Woman stars Mbulelo Grootboom and Wessel Pretorius, with set and costume design by Wolf Britz, lighting design by Mannie Manim, and music by Brendan Jury. It’s showing at The Baxter Golden Arrow Studio from 5 to 19 June.

To become a #BaxterCoffeeAngels and support the theatre in these challenging times, simply click here.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.