BOOK EXTRACT

From racial apartheid to climate apartheid – activist Kumi Naidoo in discussion with Mark Gevisser

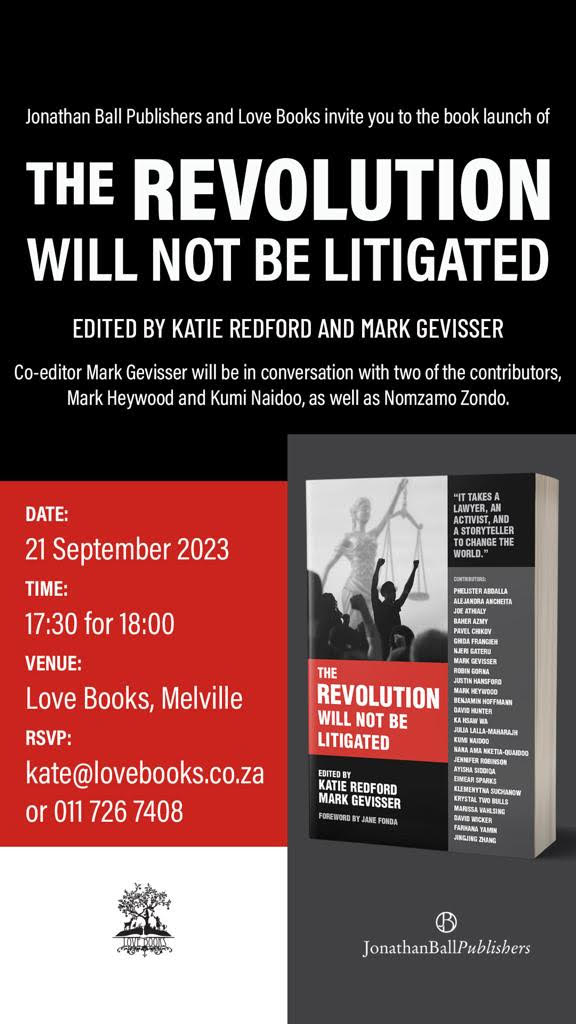

On Thursday 21 September at 6pm a new collection of essays about the uses of law in the quest for social justice, The Revolution Will Not Be Litigated, will be launched at Love Books in Melville, Johannesburg. The book’s editor, respected writer Mark Gevisser, will be in conversation with contributors Mark Heywood and Kumi Naidoo, as well as Nomzamo Zondo of the Socio-Economic Rights Institute. Below we publish an edited extract from an essay in which veteran activist Kumi Naidoo talks about relationship with the law from his days as a teenager growing up under apartheid to his stint as the executive director of Greenpeace.

Read Jane Fonda’s foreword to the book: The Revolution Will Not Be Litigated: ‘It takes a lawyer, an activist and a storyteller to change the world’

Mark Gevisser: Kumi, in your many years of activism what have you learnt about the relationship between “the power of law” and “the power of people”?

Kumi Naidoo: In 1983 there was a drought in Durban, and the council imposed water restrictions and then fines if you exceeded them. Where I lived there were blocks with only one water meter, and the excess amount was divided by the council equally amongst all tenants. If you were a single, elderly person you would be fined as much as a large family. As community activists we fought this using all the normal means of resistance, like marches, but I was in my first year studying law at university and I thought, Surely we can find a legal loophole to prove our case? I’m eighteen at the time and I take this idea to senior comrades, and one of them, Shoots Naidoo, says, “There is a good chance we’ll win in court. But we will lose a really big opportunity.”

“Isn’t the objective to win the case and justice for the people?” I asked.

“The objective is to make sure that the people feel they have won justice for themselves,” he replied. “A law firm will make clever arguments and the community will feel, ‘Oh, some people from the outside came and won the struggle for us’. They’ll lose their motivation. So let’s keep the legal option in our back pocket, and use the opportunity of this injustice about water fines to mobilise people.” Just as people today say recycling is a good place to start your activism but a bad place to end it, we were very consciously using bread-and-butter issues to mobilise people for the bigger struggle: against the apartheid state.

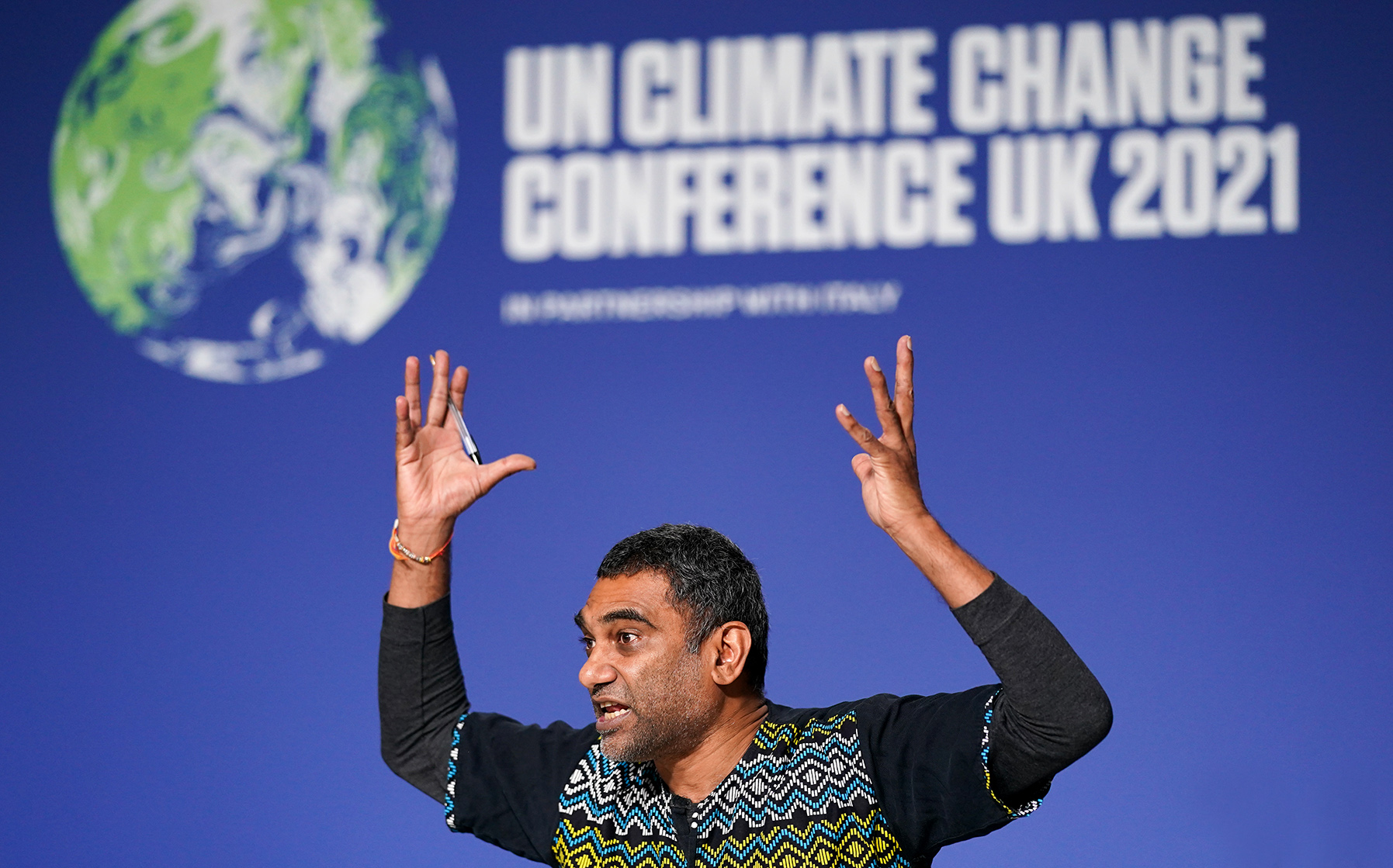

Rights activist Kumi Naidoo speaks during a meeting for the fossil fuel treaty initiative at COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland, on 12 November 2021. (Photo: Ian Forsyth / Getty Images)

I came to appreciate this wisdom. Winning a campaign is important, but winning it in a way that you are able to fight your next struggle with confidence and boldness is even more critical – even better if the next campaign goes to the heart of the unjust political system rather than simply its symptoms. Even if you win in court, it might not help you with building your movement and your bigger strategic objectives.

MG: What happened in the water fines case?

KN: We won in court, and all the fines were written off! But we only went to court after many resistance activities, including taking three busloads of grannies and grandfathers to occupy the city council. For many, it was the first time they stood up for themselves, and challenged authority and the injustice that was part of their daily lives as Black South Africans. The council responded brutally, trickling the water or cutting it off entirely. Only then did we go to court, but only after ensuring that the people we had mobilised felt a sense of ownership of the suit and understood it as part of the bigger struggle. At least forty people who emerged from that water struggle became the most active members of the association—a few actually ended up in Umkhonto we Sizwe!

MG: Do you think the mobilisation outside court affected what happened inside court?

KN: It’s a myth to think courts are completely cocooned from the reality of public opinion. Still, I couldn’t claim a direct causal link between what we did in the streets and at the council, and the fact that the court ruled in our favour. Rather, our legal argument was accepted: council policy was a public health violation. It’s an interesting lesson in using the law, even when it’s the law of the oppressor. Because even under apartheid, the South African state insisted it abided by the rule of law. If you had a good case, and a rational judge not bound by apartheid ideology, you actually could win. And so lawyers had a particular status in the movement.

International director of Greenpeace Kumi Naidoo is greeted by his daughter at Schiphol Amsterdam Airport in the Netherlands on 22 June 2011. He had been in prison for four days in Greenland after being arrested after climbing onto a Scottish oil rig in the Arctic. (Photo: EPA / Marcel Antonisse)

MG: What did these early experiences teach you, and how do you apply these lessons to the climate movement?

KN: There is a question I learned to ask in the South African struggle, that I have always tried to apply: How do you use the law to advance justice? It’s more than legal advocacy. It’s about using the law to defend the rights of people who want to speak freely; act freely; associate freely – ultimately to be able to do all those things and not be at the risk of death, as many activists around the world are today.

In South Africa we used the legal system to try to get activists out of jail. We weren’t always successful, but that wasn’t the only objective. We mainstreamed the debate by using the publicity that comes with a trial. We presented an argument not just to the judge but to the people. To those who were oppressed we said, “This is really bad, we must stand up and act against it”. And to those who were the oppressors we said: “This system is unjust, unfair, and untenable, and so it is not sustainable – the sooner you recognise the need to change, the better.”

A society moves forward when enough people understand what the truth is, and are moved to defend it or to oppose their adversaries. The biggest challenge is not how good we are at organising a march or writing a policy or climbing an oil rig, or going to court. We can be very, very good at all of that, and not make a significant enough impact. The climate emergency shows this. What we have to be really good at is communicating what we stand for to the largest number of people directly impacted.

MG: How did you become involved in the environmental movement?

KN: In apartheid South Africa, Black people thought of environmentalism as something rich white people did – after all, most white people treated their animals better than they did Black people. I’m ashamed to admit that I came very late to the movement, in around 2005, when I was chair of the Global Call to Action Against Poverty. When we realised that people in the Global South were already suffering loss of life and livelihood because of the global warming caused by people in heavily industrialised countries, we started using the term “climate apartheid” to describe this injustice.

MG: The wheels of justice turn slowly, and when it comes to the climate crisis, we’re running out of time. Should we be looking outside of the law?

KN: I’m not a defender of the rule of law under all circumstances. When I was at Greenpeace, our activists occupied a rig in the Greenlandic Arctic. They were given a judgment that was fair to us, actually, but that levelled a €50,000 fine should we ever take an action again. I made the decision with other colleagues to break that order consciously, which is how I found myself, in 2012, very nervous about my fate as I sat in a small inflatable dinghy on rough seas in freezing temperatures.

In fact it was while we were sitting in jail in Nuuk, Greenland, that I said to colleagues, “If they can use the law against us, we can use the law against them”. It was then that I began thinking about litigation as a strategy to be pursued alongside civil disobedience. I started asking questions about using more affirmative, offensive strategies to achieve our goals: “Can’t we do to the fossil fuel industry what the anti-tobacco lobby did to the tobacco industry?”

It wouldn’t matter if we didn’t win immediately; it was simply about opening up new avenues of struggle. Winning the lawsuit wasn’t as important as educating people about rights they were not yet aware of, or publicising the issue, or opening up other legal challenges that might succeed or lead to a change in legislation to address the deficit in the legal system.

MG: Do you think that becoming a lawyer is an important way to gain access to the corridors of power?

KN: One of the biggest mistakes I’ve made in my own life has been to mistake access for influence. Just because we get access to the COP (climate talks) or a national ministry in South Africa that’s doing a consultation on a white paper for some policy, doesn’t mean that we actually have influence. These exchanges are usually ritualistic and formulaic. We tick a box to say we did advocacy with the government; they tick a box to say civil society was consulted. If I reflect on my time at Greenpeace and Amnesty, I would say that 90% of the time I went into meetings, they knew exactly what I would say, I knew exactly what they would say, and both parties knew roughly where we would end up. What was the point of it all, beyond keep- ing the door open and keeping dialogue flowing? Dialogue is essential, but it alone won’t save us, particularly when we don’t listen to each other.

Executive Director of Greenpeace International Kumi Naidoo and his team give a statement at the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea in Hamburg, Germany, on 22 November 2013, when the tribunal ordered Russia to release the impounded Greenpeace protest boat Arctic Sunrise and free its crew on a bond of €3.6-million. (Photo: EPA / Christian Charisius)

MG: Where, then, would you direct people – and specifically young people – who really want to make a difference?

KN: Into activities that are building power, building numbers, building strategic mobilisation capability. I would suggest three primary areas. The first – this one might surprise you – is “artivism,” the link between arts and culture and activism, as a way to communicate to a much larger audience rather than the usual suspects to whom our politics usually speak. Then, of course, there is peaceful civil disobedience, not only for the communication value, but also because we need to allow disciplined outlets for people’s anger to be expressed. Without this, we’re going to end up with anarchic violence, which will be used by our enemies to turn the struggle against itself and be used as a propaganda tool to delegitimise it. Finally, I would suggest propositional alternatives. There are so many amazing things that mainly young people, but also older people, have come up with in terms of sustainable alternatives to the way we live. DM

Kumi Naidoo is an international activist with roots in the South Africa struggle who has led Greenpeace and Amnesty International. His latest book, Letters to My Mother: The Makings of a Troublemaker, is published by Jacana.

The Revolution Will Not Be Litigated: People Power and Legal Power in the 21st Century (OR Books), is edited by Mark Gevisser and Katie Redford, and costs R450. Read more about the book here.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

yes, everything was fine, then phoenix happened

I agree with Kumi when he explains that when people join together in the deep understanding of the slow violence that is happening, both to people and the environment, things can change. Awareness of legal rights through art and protest can bring about agency.

This is a deep theme in our country with many variables, and at this point we still have some choices.

The understanding of the asset that is environmental health which is an economic value that belongs to all people in perpetuity, but generally the value is extracted by a few, and then forever lost, is an important one to share. It is explained as environmentalism of the poor, when in fact, environmentalism should be legally forced onto industry, not the poor.

The slow violence perpetrated on society, mostly the poor, and upon the life – giving environment systems (wetlands, oceans, air ) will continue until we understand our rights and stand for them collectively. As I

understand this, the cost of failing here will be an inevitble extinction of humanity.