BOOK EXCERPT

The making of Cyclone Thuli – the story of a Public Protector and a living legend

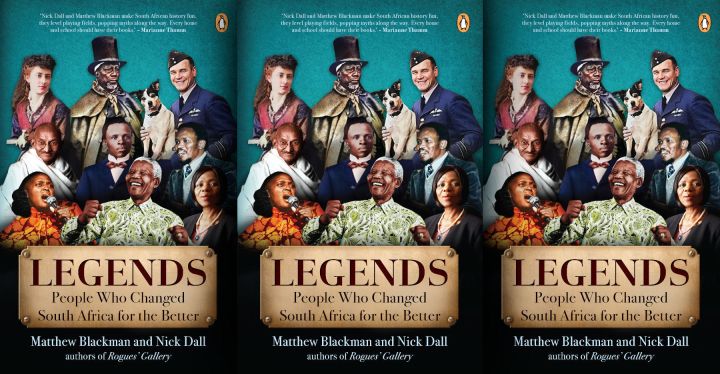

‘Legends: People Who Changed South Africa for the Better’ tells the stories of a dozen remarkable people – some well known, others largely forgotten – who positively affected South Africa.

Engagingly written and meticulously researched, Legends, the latest irreverent history by prolific writing duo Matthew Blackman and Nick Dall, reminds us that we have a lot to be proud of.

There’s King Moshoeshoe, whose humanity and diplomatic strategies put him head and shoulders above his contemporaries; John Fairbairn, who brought non-racial democracy to the Cape in 1854; Olive Schreiner, the bestselling international author who fought racism, corruption and chauvinism; and Miriam Makeba, who began her life in prison and ended it as an international singing sensation.

Thuli Madonsela is the only living legend to be featured in the book. Everyone remembers how Madonsela gracefully felled the most powerful man in the land. But few are aware of how she came to be Public Protector in the first place. This excerpt goes back to the beginning of her story. Read the excerpt below.

***

‘The Embodiment of a Biblical David’

On 18 October 2009, the newly elected president Jacob Zuma made his first big mistake. He appointed Advocate Thulisile Madonsela as Public Protector. The appointment had already been approved unanimously by Parliament – proof that the DA and the ANC have agreed with each other at least once! All that remained was for Zuma to remind her of her duties. He told the nation:

Advocate Madonsela takes on an important responsibility, having to protect South Africans against any abuse of power by state organs or officials. She will need to ensure that this office continues to be accessible to ordinary citizens and undertakes its work without fear or favour.

As Thandeka Gqubule puts it in her biography of Madonsela, with this ‘seemingly innocuous’ appointment, Zuma was ‘unaware that he was inaugurating his nemesis’.

To be fair to poor old JZ, he couldn’t really have seen Cyclone Thuli coming. He was, at the time, entirely justified in believing that no one, no matter how competent, could stand between him and the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow nation. Madonsela’s predecessor, Lawrence Mushwana, had been largely toothless and the Scorpions, the only anti-corruption watchdog with any bite, had been disbanded by the forces behind Zuma’s ascent to power.

Scouring the newspapers of the day, the only person who seems to have had an inkling of what was to come was Stephen Grootes, who wrote:

President Jacob Zuma has appointed Thulisile Madonsela as the new Public Protector. After the last guy, we’re quite excited.

The office of the Public Protector has been so weak and so useless for so long that it’s quite weird to think that, constitutionally speaking, it has considerable power.

Grootes was in no doubt of Madonsela’s chops:

Madonsela has been around for ages, one of those advocates known for having serious brains. She was … a ‘technical expert’ who helped the Constitutional Assembly draft the Constitution. We presume she still remembers most of it. She’s also been at the Law Commission for some time, and is now ready for a more public position. On the law front, her credentials are simply unquestionable.

But even he questioned whether she’d be able to navigate the political tsunamis that would come with her new role. ‘What may be more taxing for her however, is the inherently political nature of the Public Protector’s office … Madonsela’s inbox will be overflowing with complaints, many of them from the DA, that will all involve high-ranking government (and ANC) officials.’

Madonsela, it seemed, might go some way towards restoring the integrity of the office of the Public Protector. But no one expected the mild-mannered women’s rights lawyer from Soweto to become a Goliath slayer.

‘One who has silenced us’

Thulisile (‘one who has silenced us’) Nomkhosi (‘sister of the king’) Madonsela was born in September 1962, the fourth of seven children. Her parents, Nomasonto and Bafana, had left their homes in search of a supposedly better life in the City of Gold. Hendrik Verwoerd and the Nats had other ideas.

The Madonselas’ four-roomed matchbox house had two bedrooms – one of which was rented out. ‘Madonsela and her siblings … slept on the kitchen floor. There was no electricity or piped water. The toilet was outside.’ Looking back, Madonsela says, ‘I still think to some extent it’s why I don’t like small spaces.’ (Somewhat ironically, big houses would become a particular professional interest of hers.)

On 16 June 1976, a few months before Thuli’s fourteenth birthday, blood flowed through the streets of Soweto. After the uprising, Madonsela’s parents decided to send their children to Swaziland to escape Verwoerd’s Bantu Education. Thuli, who’d proved herself to be gifted academically, was enrolled in Evelyn Baring High School, a venerable Swazi boarding school that had been established for the children of British colonialists.

When she completed her Junior Certificate (the equivalent of Grade 10), her dad wanted her to return to Joburg to train as a nurse at Baragwanath Hospital. This was not unusual: teaching and nursing were the pinnacle for talented young black women back then. And he must have felt that Thuli – with her compassionate and caring nature – would make a good nurse.

His daughter had loftier goals. Like Mandela before her, she believed that the law could bring social justice. ‘Gender hit me more than race as a child,’ she told us. ‘But I knew I wanted a different world.’ Her father objected, explaining that he didn’t want her to get ‘educated to speak Afrikaans and English in order to take instructions from [white people]’. (Despite never setting foot in a classroom, Thuli’s dad frequently represented himself in court when charged with trading without a licence.)

The family priest, meanwhile, believed that by studying law ‘Thuli would become a defender of criminals’. While their cynicism was understandable, Thuli remained convinced that she could make a real difference as a lawyer. She point-blank refused to study nursing: ‘I was supposed to start on Monday. When I refused, my father stopped funding me and chased me away from home.’

Instead of getting angry, Thuli got practical. With the help of Mr Ginindza, the principal at Evelyn Baring, she got a bursary to return to Swaziland and complete her education. True to form, she also managed to maintain a decent relationship with her dad. After getting her O Levels in 1979, she worked as an assistant teacher: first at Evelyn Baring and then in Soweto.

Amaqabane: The activists

Madonsela returned, older and wiser, to a changed township. As Gqubule puts it, ‘she had left a Soweto that was simmering down, and returned to a Soweto ablaze with new campaigns – new forms of struggle and expression. Young and public spirited, she threw herself into “those whirling campaigns”, sparing no effort.’ In the early days, Madonsela told us, her activism involved ‘conscientising people, delivering pamphlets and attending rallies’.

Living with her parents in Soweto once again, and teaching at Naledi High School, Madonsela rediscovered her community. She joined the Dlamini Civic Association and explored her passion for social justice. As a teacher at Naledi High, she was exposed to a younger and more militant generation of political activists:

The generation of 1976 and the 1980s blamed their parents for internalising the messages of inferiority and docility – for the silence between moments of heightened political struggle. This younger generation eschewed the politics of survival and individual self-preservation, and embraced action in the collective.

Instead of berating her students, Madonsela, still only in her early twenties, joined them. In 1984, she stopped teaching to study law at the University of Swaziland. In the same year she joined, at the invitation of Zwelakhe Sisulu (Walter and Albertina’s son), the tiny National Union of Printers and Allied Workers (NUPAWO) as a legal and education officer.

Activist. Trade unionist. Law student. At just twenty-four years old, Thuli Madonsela already had a very clear idea of the kind of future she wanted for herself and her country.

The UDF, COSATU and the inzile-exile dilemma

One of the reasons for apartheid’s longevity was the way in which the Nats were able to divide and conquer. This changed in the 1980s when PW Botha’s plan to co-opt Coloureds and Indians into the system at the expense of black people united the opposition like never before. What had previously seemed like irreconcilable differences between Coloureds and blacks, Muslims and Christians, and communists and capitalists suddenly paled into insignificance. All that mattered now was to show PW the middle finger.

Allan Boesak, the outspoken Coloured priest who’d been expelled from the Dutch Reformed Church for declaring apartheid a ‘heresy’, campaigned to get ‘churches, civic associations, trade unions [and] student organisations’ to unite in their opposition to the apartheid government’s planned reforms. The United Democratic Front (UDF) was launched at a ‘chaotic, crowded and euphoric’ meeting in Mitchells Plain on a bitterly cold day in August 1983. Soon the UDF numbered almost 1 000 different organisations from all segments of South African society, including Madonsela’s Dlamini Civic Association.

In 1985, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU, of which Madonsela’s NUPAWO was a founder member) was established. Almost overnight, COSATU (bolstered by Cyril Ramaphosa’s National Union of Mineworkers) boasted half a million members. Never before had the apartheid government encountered anything close to this kind of homegrown, multiracial opposition. As Michigan State University’s ‘Overcoming Apartheid’ project explains, ‘The combined power of the UDF and COSATU was a major factor in forcing the apartheid regime to negotiate.’

This hurricane of discontent hastened the end of apartheid. But it also set up a conflict between the exiled leaders of the ANC who had been fighting for freedom since the 1950s, and the so-called inziles – people like Ramaphosa and Madonsela – who, despite arriving far later at the party, had still played a major role in the liberation of the country.

When the ANC came to power in 1994, most of the senior positions went to exiles. As Mark Gevisser asked, ‘if “exile” becomes the “state”, then are those at home not in fact exiles?’ Fast-forward to the 2010s, and the struggle between Madonsela and Jacob Zuma can be seen on some levels as the factional conflict between inzile and exile. Zuma, after all, had risen through the ANC ranks while exiled in Mozambique and Zambia; Madonsela was a child of the UDF and the trade unions. DM

Legends: People Who Changed South Africa for the Better by Matthew Blackman and Nick Dall is published by Penguin Random House SA (R320). Visit The Reading List for South African book news, daily – including excerpts!

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Here we are celebrating the catalyst that allowed the state capturerers to take control.

Investigative reporting in South Africa is dead.

Methinks you are missing the point of this article entirely. This report fills me with humility and admiration.