DOCTORS FINDING SOLUTIONS

Stitching up the gaps: The vision of a paediatric surgeon determined to expand care to rural South Africa

As important to Dr Elliot Motloung as the histories of black doctors in South Africa, was the mentorship of Prof Nyaweleni Tshifularo, a trailblazing paediatric surgeon surgeon. He encouraged and supported Motloung through his training and gave him the impetus he needed to start carrying out his mission of expanding paediatric surgery to rural provinces.

In his rooms overlooking the granite hills of Mbombela, paediatric surgeon Dr Elliot Motloung scribbles on a prescription notepad. What he outlines is not just a treatment plan for a single patient, but a blueprint to expand access to quality, equitable paediatric surgery in all of South Africa’s provinces.

Motloung circles Limpopo, Mpumalanga, North West and Northern Cape on his sketch map. Just five years ago, none of these four provinces had a single paediatric surgeon in either private or public healthcare. A 2018 study by researchers at the University of Cape Town showed that this absence left “4.5 million children in these predominantly rural areas without specialist paediatric surgical providers”.

Motloung had one question: “All those kids, what happens to them?”

If children in those provinces experienced emergencies needing surgery, they had to travel to hospitals mostly in Gauteng, home to the bulk of South Africa’s paediatric surgeons. Making arrangements to travel hundreds of kilometres with specialised paramedics can take up to 36 or even 48 hours, says Motloung.

“That’s how the deaths come about.”

Dr Elliot Motloung (middle row, third from right) gathered support from local businesses and communities to upgrade a ward at Rob Ferreira Hospital, Mbombela, into a state-of-the-art paediatric surgery unit. (Photo: Supplied).

Today, after leading the creation of two public paediatric surgery units in Limpopo and Mpumalanga, Motloung crosses these two provinces off the list of those without paediatric surgery care. If no one else starts state paediatric surgery wards in the North West and Northern Cape, Motloung says, “I know where I am going.”

From loss to ambition

Motloung’s passion for expanding access to surgery in rural South Africa is rooted in his childhood. He was raised by his grandmother, a domestic worker, in Trompsburg, a rural Free State town so small it had just one doctor.

When Motloung was in his adolescence in the early ’90s, his grandmother developed breast cancer. Waiting with her for hours outside the doctor’s rooms in the icy cold Free State mornings was how he was introduced to the inequities of healthcare in South Africa. He noticed separate entrances for black and white patients and how the queues for black patients grew longer while white patients who arrived later were helped first.

Accessing the cancer treatment his grandmother needed in far away Bloemfontein was impossible.

“My grandmother died without her surgery. At the time… she was the only parent I had. And I thought, I want to become a surgeon. Why are people dying without an operation? That’s where my love for surgery started.”

After his grandmother’s death, Motloung lived with his uncle, who died a year later of lung cancer without being able to access quality care.

‘There is no way I’m not going to become a surgeon’

Motloung held on to this dream through school in Trompsburg, where he says he was initially fortunate to have good teachers. But in grades 10 and 11, when his science and maths teachers left without being replaced, he took on the role of teaching his peers those subjects.

He soon realised that to get into medicine at university, he needed to finish Grade 12 at a better-resourced school. He had his eye on Navalsig, a boarding school he had seen through taxi windows whenever he visited Bloemfontein.

Living with his mom who was unemployed at the time, he was unable to afford school fees. But at the start of his matric year, Motloung arrived at Navalsig and managed to persuade the headmaster to allow him to study and board without paying fees.

Nurses and community service doctors at the paediatric surgery ward at Rob Ferreira, Mbombela, provide children with life-saving care. (Photo: Supplied).

“I met fantastic teachers but I was very behind. I remember in the first maths class my teacher said we must draw a hyperbola. Hyper-what? I had never heard the word. I realised that all of my high school I was doing algebra and geometry, we had not done trigonometry… so that was a big catch-up,” Motloung says.

Through the friendship of his roommate and ceaseless early-morning study sessions with top-performing classmates, Motloung went from having the lowest marks in his grade to finishing matric ranked close to the top of his class and in the top 100 in the province.

But because his Grade 11 marks weren’t strong enough, he had to use the same persuasiveness that got him into Navalsig to convince the administration of the University of the Free State to enrol him in medical courses.

He remembers deciding, “I am going to go sit outside that office every day.” Eventually, the administrators relented and made an exception for him, vowing never to allow someone else to do the same.

Finding purpose

In his fourth year of studying medicine, Motloung inadvertently walked into the wrong operating theatre. Here, he saw paediatric surgeon Dr Esme le Grange performing a complex operation to save the life of a child.

Motloung recalls that this moment made him realise, “This is it.”

Not just any surgery, but paediatric surgery was to become his passion.

Years later, after finishing community service, Le Grange insisted that Motloung specialise with her.

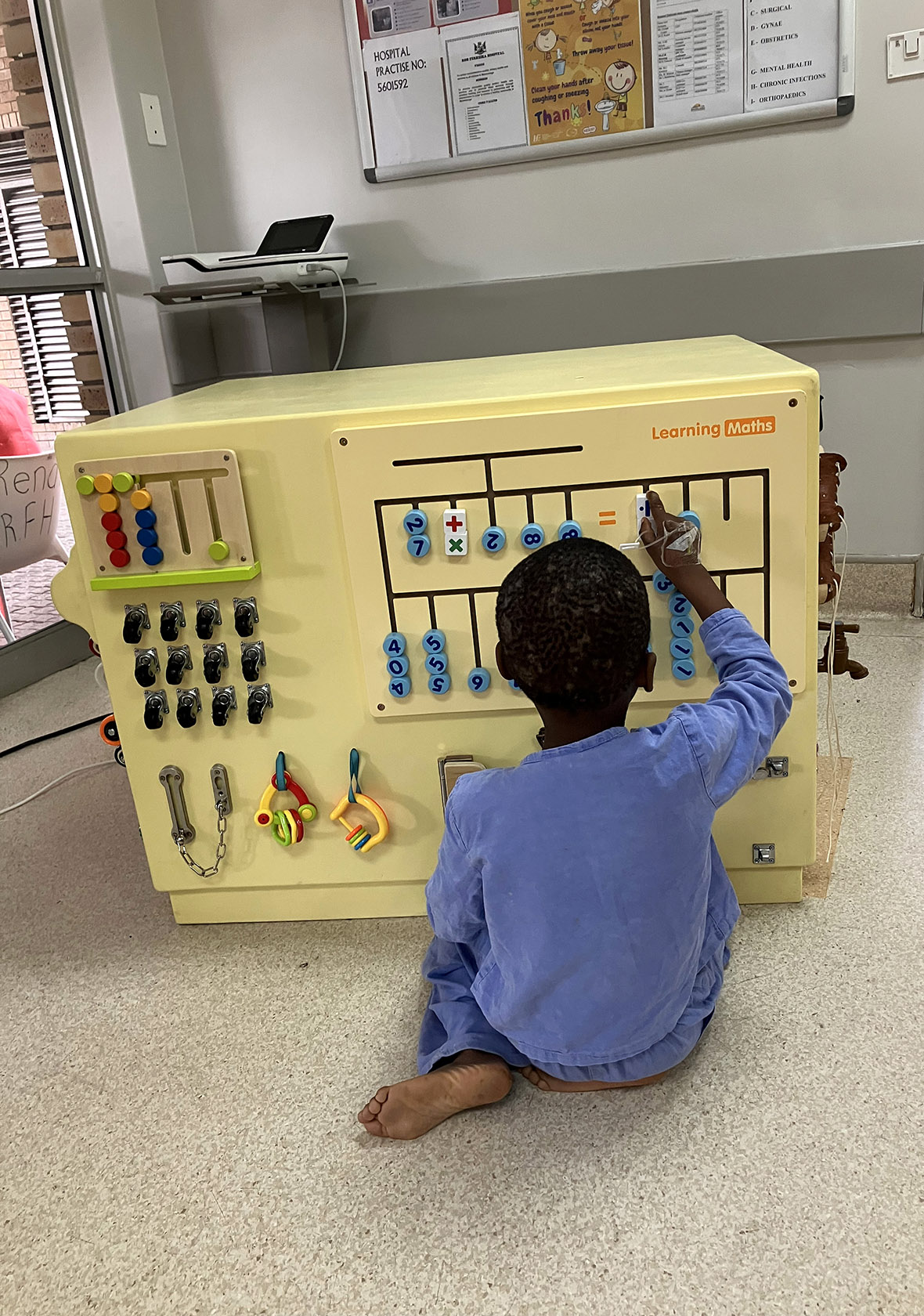

A busy box at Rob Ferreira’s paediatric surgery ward in Mbombela helps children pass the time in hospital. (Photo: Supplied).

Specialisation in paediatric surgery was immensely taxing. Motloung says his life began to unravel as he fell into depression and lost his marriage.

“Those five years were the worst five of my life… I suddenly hated the one thing I had wanted all my life,” he says.

So close to finishing, but having lost motivation, Motloung took a year off. He travelled around South Africa, often living out of the back of his car. To earn an income, he occasionally assisted other surgeons.

During this time, he found direction by researching the history of black medical doctors in South Africa. He discovered how black doctors in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were forced to train outside the country and did not receive recognition once they returned, but still provided quality healthcare to their often rural communities.

Motloung compiled this history into a manuscript that is currently with a publisher.

“Their stories reminded me why I wanted to become a doctor in the first place… [they] said to me, ‘rural health matters’.”

Limpopo’s first paediatric surgery department

As important to Motloung as the histories of black doctors in South Africa, was the mentorship of Prof Nyaweleni Tshifularo, a trailblazing paediatric surgeon. He encouraged and supported Motloung through his training and gave him the impetus he needed to start carrying out his mission of expanding paediatric surgery to rural provinces.

Motloung recalls Tshifularo telling him that he had a job for him: to start a paediatric surgery department at the University of Limpopo, in one of the four provinces without the specialisation.

Mpumalanga’s first paediatric surgery ward was opened at Rob Ferreira Hospital in Mbombela in 2022. (Photo: Dr André Hattingh).

Daunted by the prospect of starting a department from scratch, Motloung says that Tshifularo’s experience and support were instrumental in working through challenges. Added to this, “there was political will from the Department of Health in Limpopo to support paediatric surgery”.

Today, Limpopo has a “fully-fledged paediatric surgery unit where all children that need surgery can access it”. Motloung worked with other doctors to establish a master’s programme in paediatric surgery at the University of Limpopo.

Within a few years, the department had “four paediatric surgeons [and] we had six doctors who were training… more paediatric surgeons than a unit like the University of Pretoria,” Motloung says.

Equitable access to quality care in Mpumalanga

With the department in Limpopo running smoothly, Motloung felt it was time to continue his mission of expanding access.

“This was a problem for me,” he says, pointing to Mpumalanga on his sketch map. “There was no paediatric surgeon in Mpumalanga, private or public.”

Motloung moved to Mbombela and set up a private practice.

“I remember I was sitting here thinking, but the kids who don’t have medical aid are still dying.”

After waiting months for approval from the provincial Department of Health, in August 2022 Motloung opened Mpumalanga’s first paediatric surgery ward at Rob Ferreira, the state hospital in Mbombela. For just over a year, with the help of a team of passionate community service doctors and nurses, the unit has provided life-saving care to hundreds of children.

“It’s not about just providing care, it must be the current cutting-edge surgery,” Dr Motloung says. He specialises in the most innovative camera-aided minimal access surgery to reduce pain, recovery time and complications.

“If I don’t know how to do it, I go and train,” he says. He has received training in surgical leadership at Harvard and is currently working towards an additional master’s at Oxford.

‘Better than the NHI’

Motloung is determined that, at his unit at a public hospital, “patients are going to have the same state-of-the-art ward and theatre structure as any patient with medical aid.”

To meet his vision for equitable, quality healthcare at Rob Ferreira, Motloung drew on the support of local businesses, nonprofits and community members to renovate a dilapidated ward into a brightly decorated, well-equipped, specialised paediatric surgery unit.

He says the renovations have improved the environment for nursing and medical staff, which, in turn, translates to better patient outcomes.

“The state spent nothing,” he says of the upgrades.

Motloung sees this experience in creating the first public paediatric surgery department in Mpumalanga with the support of communities and private hospitals as a model for how shortcomings in the province’s “collapsed” public healthcare system should be addressed.

“Healthcare should not depend on whether you have money or not. That’s why the government, the NGOs and private hospitals, these three parties, should be able to bridge the gap between funding,” he says.

Residents help renovate an old ward at Rob Ferreira Hospital, Mbombela in preparation for Mpumalanga’s first paediatric surgery department. (Photo: Supplied).

Motloung cites examples of how this has worked in his practice. In a complicated case of conjoined twins he operated on last year, a private hospital agreed to provide theatre time and beds for the patients who were without medical aid or means to pay. Appeals for community help have secured customised, 3D-printed prosthetics for a patient with severe burns.

“I think if we get that right, it’s better than the NHI [National Health Insurance]…The NHI doesn’t solve the problem,” he says.

Motloung sees budgets being misspent and staffing shortages as the biggest challenges facing South Africa’s public health system. He believes that with the NHI, healthcare in South Africa will continue to suffer.

“As long as they do not fix the administration, they don’t fix the employment, the human resources and the procurement processes, they can change all the systems, it will not work.”

More work to do

Winter and the fires people make to keep warm bring a sharp uptick in the number of children who arrive at paediatric surgery wards with serious burns. Motloung says, “I get a minimum of 10 children every week with severe burns and I have got nowhere to put them.”

Motloung is gathering contributions to set up a specialised paediatric burns ward at Themba Hospital in Kabokweni. He says Mpumalanga needs a centralised place to focus on providing care to children with burns and to host outreach on burns prevention and treatment.

Anyone prepared to help make the Themba burns ward a reality through donations or other support is encouraged to contact Pediatric Care Africa, an NGO that Motloung works with in Mbombela, and use “Themba” as the reference.

With two paediatric surgery units established and another in the works, Motloung’s mission is far from over.

“I wish one day when I retire, paediatric surgery services will be accessible to every child in South Africa, everywhere.” DM

Stories like these give me hope for the future of South Africa. Bravo Dr Motloung.