HOT RECEPTION

Zululand community members blockade roads, telling India’s Jindal Steel & Power to ‘voetsek’

India’s Jindal Steel and Power group has met a very hot reception committee in the hills of Zululand following its renewed push to dig massive iron mining pits on community land.

A look verging somewhere between anger and despair forms on the face of 69-year-old Simon Zulu as he jabs his walking stick into the ground repeatedly.

“We have told Jindal many, many times that we don’t want them mining our land. No mining! No mining! But they just won’t listen…” he fumes.

Somehow, his spectacles remain perched on the bridge of his nose as he shakes his head vehemently or pounds his stick down to emphasise his frustration.

Zulu, an elder and prince of the local Entembeni royal house, is among the several hundred rural folk – possibly thousands – who stand to be pushed from their homes and farms, or to dwell next to a massive iron mining operation for the next century.

Prince Simon Zulu is determined to remain on the land where his family keeps cattle and goats and also grows vegetables and fruit. (Photo: Tony Carnie)

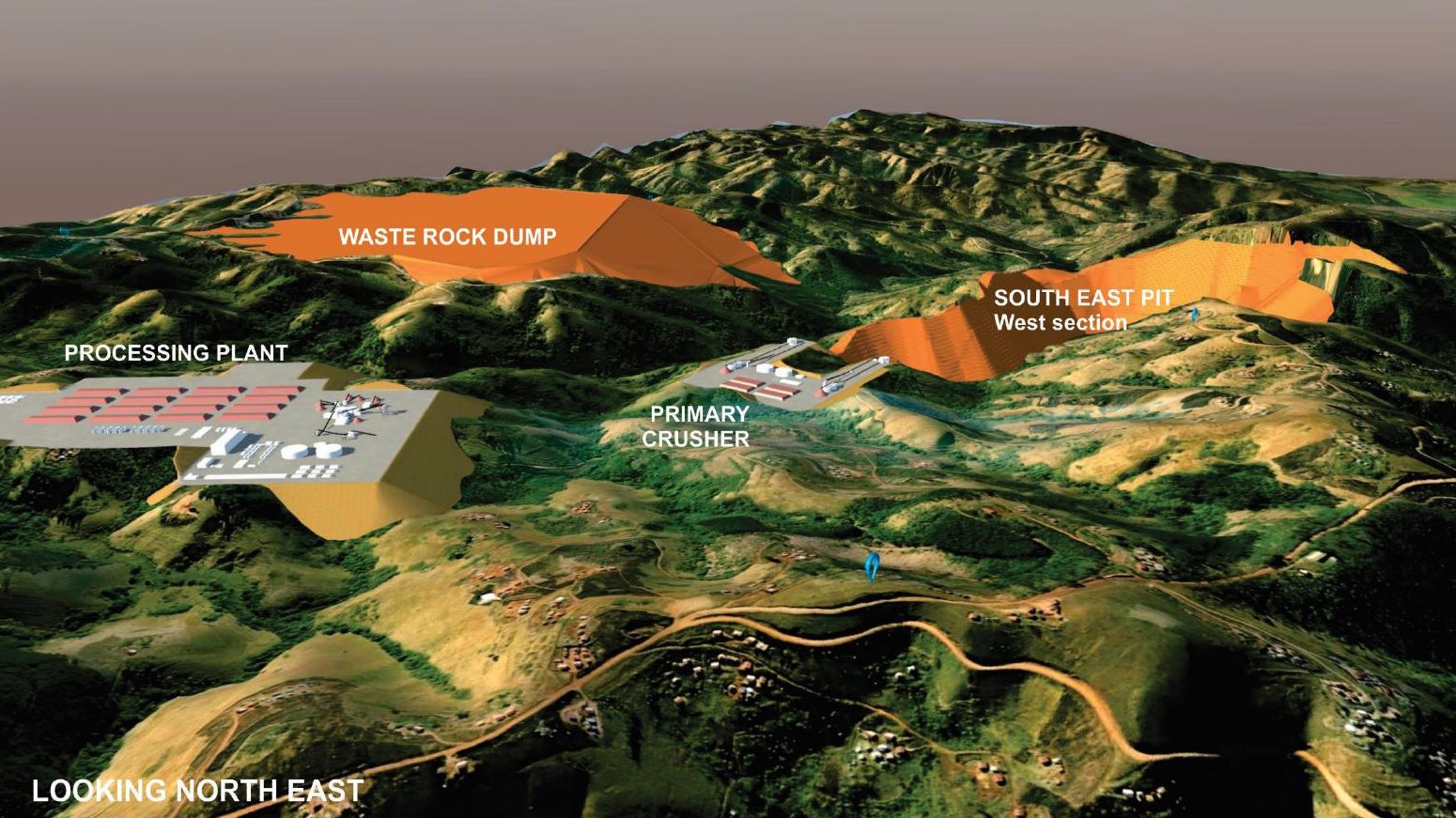

The first pit would be 4km long, 1km wide and five times deeper than the length of a 100m rugby field. From such vast pits, Jindal hopes to scoop and then export iron-rich magnetite crystals for steel production in India and China.

If the project goes ahead, it would take 25 years to exhaust the first pit. As Jindal is seeking government mining rights on a land area covering more than 20,000ha, it is conceivable that several other pits will be established incrementally if the commodity prices remain attractive. Jindal geologists calculate the main ore body could last 100 years.

Residents whose homes fall outside the mine’s 500m exclusion zone will not have to move, but nevertheless seem destined to live the rest of their lives in close proximity to the daily, grinding machinations of an open-cast mining operation roughly halfway between the towns of Eshowe and Melmoth in the historic heartland of the Zulu nation.

Jindal has yet to publish a list of the exact number or location of homes, schools, community halls on the demolition or relocation list, but has indicated that “more than 350 households would need to be relocated” to make way for the first pit and associated crushing and processing plants.

Based on preliminary maps in the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) documents, however, at least two schools are located above the mining pit or within the 500m exclusion zone. (That exclusion zone is based on the hazards of flying rocks, noise and dust clouds from blasting operations).

Jindal only wants the good stuff, so there will be a lot of waste left behind. Just one quarter of the 32 million tonnes of rock material blasted from the pits each year will be exported. The other three-quarters (24 million tonnes per year) will be carted to a nearby waste rock dump or to a separate slurry dump (tailings storage facility) in the Nkwaleni Valley.

An architect’s impression of the proposed Jindal mine. More than 350 households face eviction from their land in the hilly terrain near Melmoth if the mine is authorised. (Photo: Graham Young Landscape Architect)

The slurry dump alone would cover an area of 8km² and stand nearly 83m high – almost as high as the neighbouring Phobane (Goedertrouw) Dam wall – a vital reservoir which provides water to local residents, irrigation farmers and major industries as far away as Richards Bay.

So – despite all the hoopla around a multibillion-rand foreign investment scheme and promises of up to 800 new direct jobs and 57 939 indirect spin-off jobs from the New Delhi-based steel and power company – perhaps it should have come as no surprise that scores of directly affected local community members rose in the early hours last week to stick a spanner in the works of Jindal’s mandatory public consultation process.

(These consultation meetings are required by law in terms of the EIA regulations and mining rights approval processes by the Department of Mineral Resources.)

The “welcome reception” began shortly after midnight on 26 June, when the first of several piles of logs and branches were placed on local dirt roads, as well as the busy provincial tar road between Eshowe and Melmoth. Several large trucks were stopped around 2am and the drivers instructed to park their vehicles to blockade the town.

Then the keys to the trucks vanished.

Local residents display a protest banner during a road blockade near Melmoth on June 26. (Photo: Supplied)

The result was that no north-bound vehicles were able to enter Melmoth – the venue for the first of a series of “information-sharing meetings” facilitated by Jindal consultants SLR and Zutari.

While vehicle access to Melmoth was still open from the north, this was only possible using the much longer back-road routes via Ulundi or Nkandla.

Daily Maverick, unaware at the time that the road blockade outside Melmoth was linked directly to the mining controversy, opted for the windy route via Ulundi to cover a mid-morning Jindal consultation meeting. But when this reporter eventually reached Melmoth around lunchtime, officials from SLR, Zutari and Jindal were busy locking up the meeting venue after receiving advice from the SA Police Services and local municipal leaders to cancel all meetings.

A second consultation meeting, scheduled with local commercial farmers at the Nkwaleni Farmers Hall on 27 June, was also called off by Jindal in the wake of the Melmoth protests.

Women sort oranges at a citrus packaging plant in the Nkwaleni Valley. Local farmers fear that the region’s scarce water resources will come under further threat if a new iron ore mine is authorised. (Photo: Tony Carnie)

Nearly 13 hours after the protests started, the blockade was still in place. The protesters made it clear that they were not going anywhere until Jindal collected their two-page memorandum of complaints.

Contacted for Jindal comment, a senior official who asked not to be named, has condemned what he described as the “violent unlawful protest”.

“Jindal’s stakeholder engagement manager was aggressively harangued by the protesters and instructed to pack his belongings and leave Melmoth. It was necessary for him to receive an armed police escort as he left. The protesters also insisted that Jindal stop their meetings and close their Melmoth office.”

“We do not believe that the illegal protest activity [that] took place on 26 June is a true reflection of the sentiments of affected community members. The company does not believe the community of Entembeni is against the proposed development.”

But community sources were adamant that no one was harmed physically, nor were any of the trucks looted or damaged by protesters during the blockade.

The latest events were precipitated by the publication of a voluminous EIA report by Jindal consultants on 14 July, giving affected stakeholders just 30 days to comment on a project with massive ramifications for the region’s people, economy, scarce water resources and environment.

A summary report by the SLR consultancy report asserts that: “When resettlement is done properly, all affected households are negotiated with, no households are forced to move” and that “the relocation of people would be undertaken in accordance with best practice guidelines.”

Hundreds of homesteads are clustered in the hills above the Phobane Dam. During the 2016 drought, the dam level dropped to below 17% of full capacity, leading to significant water restrictions. (Photo: Tony Carnie)

But that is not how many directly affected local residents see things.

Speaking from her home in the hilly terrain above Phobane Dam, local mother Zibuyisile Zulu said: “We want the mine officials to come to us – it’s not for us to go to their meetings to discuss our futures.”

According to Zulu, local residents have made it clear to Jindal that they are not welcome to mine here.

But is her community not desperate for the jobs and other economic opportunities offered by Jindal?

“We have heard too many empty promises over the years and I don’t think any good will come from the mining,” she responds.

Quite apart from the social and emotional trauma of being evicted from their homes and land, she fears that those left behind run the risk of respiratory disease from dust; water pollution; water scarcity; cracked houses from blasting operations; the loss of grazing land or the trauma of exhuming ancestors and loved ones from family burial grounds.

“This area is very peaceful. There is no crime. There are many things that are good in this place. There is good grazing land for cattle and goats and we also rear chickens and grow our own vegetables.”

Dlozeyane Primary School is almost directly above the proposed Jindal iron ore mining pit. (Photo: Tony Carnie)

Recalling the murders of anti-mining activists Bazooka Radebe and Fikile Ntshangase, she fears that powerful figures who stand to benefit financially from the Jindal mine could seek retribution after the recent Melmoth blockade.

“There is a possibility they will now come to ambush us one by one.”

This sense of fear was shared by another community leader who lives close to the first proposed pit.

Speaking on condition that he not be identified as he fears for his safety, the elder said: “It concerns me that our peace will be disturbed when the mine comes. I am worried about having to move and losing my land. Even if we don’t have to move, how can we exist living next to such a big mine? We will lose many things as this mine expands.

“Even our graves will be affected. Our brothers and parents and grandparents are resting there and should not be disturbed in their peaceful sleep.

“How can we allow mining? Those who come after us will ask: ‘How did our parents allow these things to happen? Why did they accept a disaster?’ No, a mine in this area will not be accepted by us. We have stated our position many times but they won’t listen.”

The EIA summary report by Jindal consultants pledges that: “No graves will be exhumed and moved to another location without the full consent of a household” – a tall promise to keep considering the experience of several communities when the mining bulldozers arrive.

Local land activist Mbhekiseni Mavuso fears that his life is already in danger because of his role in mobilising community resistance to the Jindal project.

Mbhekeseni Mavuso, a prominent land rights activist, is a vocal critic of the plan to mine magnetite iron ore near Melmoth. (Photo: Tony Carnie)

“When Jindal first came here to propose mining in 2011, I started mobilising residents and had to go into hiding for several weeks in 2013 when some people started saying that ‘Mavuso must be killed’. Even now it is tense and I will have to move somewhere for safety after the latest protest.”

Mavuso, the KwaZulu-Natal coordinator of the Alliance for Rural Democracy, has been campaigning on behalf of black rural residents since the late 1980s. This included mobilising the eMacambini community against proposals by the Dubai-based Ruwaad group to develop Amazulu World, a new game reserve, entertainment centre and upmarket housing estates near Mandeni north of Durban.

“I hate mining,” he declares, “It damages peoples’ land and their rights to land because they are not consulted. Too often, developers are very happy to talk to governments, business people, chiefs and municipalities – but not to the people who are directly affected. They don’t respect rural people. They only respect rich people. They take away people’s homes and land. They disturb graves. They don’t respect culture or our connection to our ancestors and they ignore the fact that the land is the source of all our food – and that without land, you are like an orphan.”

But the government approval clock is ticking away fast, despite suggestions by Jindal metallurgy consultant Patrick Donlon, that the project is “still some way away” because first production from the mine was only scheduled for early 2031.

Yet, a closer reading of SLR’s project summary documents suggests that Jindal could send in bulldozers as early as 2025 to commence the bulk earthworks ahead of the construction of the main crushing and processing plant.

And now, following the cancellation of the meetings last week, it remains unclear when commercial irrigation farmers will get to raise their concerns around one of the most controversial aspects of the Jindal proposal – where will the water come from to feed such a massive mine?

The deadline for public comments on the EIA report expires on 14 August 2023. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

If this mining is approved it should be on the condition that the ore should not be exported but it should be smelted in South Africa for subsequent export.

Right. Why give a foreign country all that iron? We made steel in Newcasle for years, we do it again.

then how will gweezy get to “eat”?

Indian companies are extreme labor abusers. Look into their call centre operations in India and Africa. They will create low paying jobs and bring in India management. Who stands to benefit ? No downstream development. Who are their BBBEE partners, that investigation should shed some light !

Surely, this will follow the same old pattern with a handful of connected individuals standing to benefit richly from this mining operation, talking up jobs and houses and “development”… but those who farm and nurture the land will have to make way for the destruction of their environment, appropriation of their water supply and polluting the air… open pit mining is a scourge.

All comments seem to feel that it is a done deal, just like the situation in Eastern Cape?

Surely the feelings of the community should be considered?