SPOTLIGHT RISING STAR

Growing the Beta variant — young scientist remembers the day they danced in the lab

During South Africa’s Covid-19 hard lockdown, rising-star scientist Dr Sandile Cele spent his Christmas holidays working tirelessly. It led to the 35-year-old being the first to successfully grow the Beta variant of SARS-CoV-2 in the lab. Tracking his process, the accolades that followed, and his leap onto the global scientific stage.

In a Durban laboratory in 2020, there were scientists dancing and jumping for joy when Dr Sandile Cele realised they had finally successfully “grown” the SARS-CoV-2 Beta variant. Despite being the holiday season, Cele and a few colleagues had sacrificed their Christmas to continue research at an otherwise deserted laboratory.

The Beta variant (501Y.V2) was first detected in the Eastern Cape in October 2020, and was announced to the public on 18 December that year.

“It was December 2020 and Tulio [Professor Tulio de Oliveira] had just flagged the Beta variant and we had been struggling trying to grow it, really struggling for about two weeks,” says Cele. “But then as a scientist, you have to think outside the box, and eventually it [the virus] did catch on. I was with Professor Alex Sigal that day in the laboratory. We were so excited. There was a lot of dancing in the lab, jumping up and down…”

The 35-year-old scientist’s work on the Beta and Omicron variants helped propel South Africa to the forefront of Covid-19 research. Cele is credited with growing both Beta and Omicron in record time, as the world reeled under lockdown pressure. Last year, he was awarded a special ministerial Batho Pele excellence award for his contribution to Covid-19 research in South Africa.

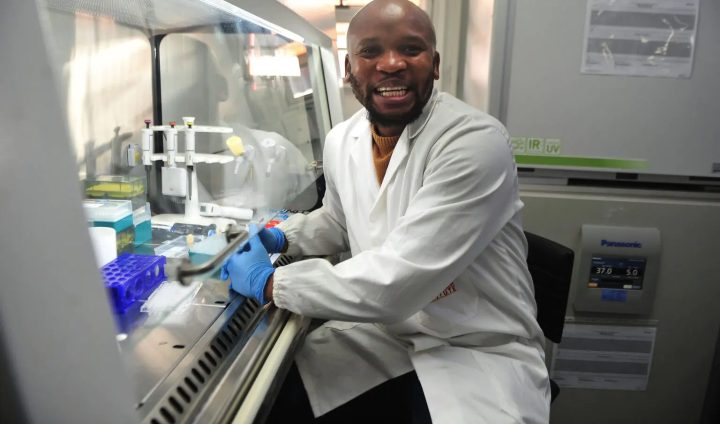

Cele was working inside a state-of-the-art biosafety level 3 (BSL-3) laboratory at the Africa Health Research Institute, when he grew the Beta variant. (Photo: Rosetta Msimango/Spotlight)

Moment of greatest fulfilment

Cele says growing the Beta variant was his moment of greatest career fulfilment so far.

“It was just a crazy, crazy moment. Like, you know when you are with your superior, usually you meet on a basis of respect. I mean, you talk seriously. They ask a question, you answer, and so on. But [at] that moment, all that got thrown out the window. We were celebrating. So yes, it was really special.”

They were leaping for joy under a layer of PPE (personal protective equipment), including specialised masks, double gloves, plastic sleeves, and boots. Cele points out that with all the safety measures in place, infection risk was smaller in their lab than at an average mall.

Read more in Daily Maverick: South Africa’s scientists say the 501Y.V2 variant moves more easily and faster, but it’s not more deadly

He was working inside a state-of-the-art biosafety level 3 (BSL-3) laboratory at the Africa Health Research Institute (AHRI). The lab is on the third floor of the University of KwaZulu-Natal’s (UKZN) medicine building. On the first floor of the same eight-storey glass and face brick building, De Oliveira had been studying virus samples for genetic clues at KRISP, the KwaZulu-Natal Research and Innovation Sequencing Platform, from where the discovery of Beta and Omicron was first announced.

How the Beta variant was grown

Cele explains that viruses are isolated or “outgrown” by infecting cells in the laboratory, using swab samples from infected individuals.

“Growing a virus simply means isolating it from an infected host (humans) and making more of it in the lab for research purposes,” says Cele. “You cannot study a virus within an infected person, especially a new virus. You need to have it in the lab for identification and clarification. Usually, you get small quantities from an infected person, thus you have to expand or grow – or make more of it – for research.”

However, the Beta variant had not responded like previous SARS-CoV-2 variants. At the time, Cele found a creative solution using both human and monkey cell lines. First, he infected human cell lines with the Beta variant, incubating the assay for four days. Then he used the infected human cell lines to infect monkey cell lines, which successfully led to production of the virus.

Their moment of triumph arrived when they noticed the monkey cell lines starting to die, meaning that the virus was growing. The isolated virus could then be used in the laboratory to run experiments, like testing vaccine efficacy.

“Looking at the cells under the microscope, you can see them starting to die,” he says. “That they’re not happy. That they have been infected, which then obviously needed to be confirmed.”

While Cele’s Durban mentors – De Oliveira and Sigal – kept the public abreast of research developments, the young scientist kept his head down, pouring over his microscopes. “The world was going crazy, everything was crazy, but I had work to do,” he says.

The scientist’s work on the Beta and Omicron variants helped propel South Africa to the forefront of Covid-19 research at work. (Photo: Rosetta Msimango/Spotlight)

A rising star

Cele readily shared anecdotes and laughed often during the interview.

From Ndwedwe, a rural area 40km north of Durban, Cele joined Sigal’s laboratory team at the AHRI in 2014, where he studied HIV drug resistance and later Covid-19. His PhD from UKZN in 2021, focused specifically on understanding the Beta variant and its escape from antibodies.

“Actually, Professor Alex Sigal really took a chance on me,” he says. “On that post for a laboratory technologist, they stipulated that they wanted someone with three years experience. And I had only been doing my internship [at Technology Innovation Agency] for eight months.”

Sigal’s faith paid off, and he subsequently praised Cele in national press interviews on Covid-19. “Sandile is a rising star who spent all his holidays in a laboratory,” Sigal told media in January 2021.

Last year, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation invited Cele to present his findings at the Grand Challenges Annual Meeting in Brussels. This was his first time abroad. “It was my first time travelling outside South Africa, and my first time talking in front of so many people. I presented my go-to talk – based on a paper I did on Covid-infection and HIV – and it went well,” he says.

Trailblazer

Earlier this year, Cele was named one of Mail & Guardian’s 200 trailblazing young South Africans in the technology and innovation category. He could not attend the gala event, as he was at the University of Nairobi in Kenya for training relating to a project involving HIV research for the Aurum Institute. Cele started a new job at the Aurum Institute in Johannesburg in March.

Cele spoke from his new home in Johannesburg, via Zoom. He was wearing a fluffy blue robe over his clothes, laughing as he spoke about how cold Johannesburg was for somebody originally from Durban.

In Ndwedwe, Cele was one of 10 boys born to his father, who was away from home often for work. Describing his mother as “a busy lady”, Cele says she was the one who shaped his young daily life. Growing up in a mud hut without electricity and running water, he recalled how his mother got up early every morning to prepare vetkoek, which she sold at a local school, and to boil water so her children could have a bath before leaving for school.

In the afternoons, he looked after his father’s goats and played soccer. He says that as a child he preferred herding goats to cows, as goats grazed for only about five hours, whereas cows took all day to eat their fill. From Grade 9 onwards he attended Overport Secondary School in Durban.

Cele hails from Ndwedwe, a rural area 40km north of Durban. (Photo: Rosetta Msimango/Spotlight)

No shortcuts in life

A childhood memory that inspired him? “Before my mother died, she sat us down and said: one day I will be gone and I want you to know there are no shortcuts in life. Work hard and look after one another, and you will be okay.”

His mother’s death was sudden, following complications from minor surgery.

“Like, I came back from school on a Friday, only to find my father wasn’t around and had left a note… On the Saturday morning, I found out my mother had passed. And I think she went for, I don’t know, an operation or something. But as a kid, I guess they didn’t tell us because they thought it was something minor; that she would get operated [on], then go back home. I’m not really sure what happened. So, yes, it was a sudden death.”

The year after his mother died, Cele’s matric marks suffered. He says his final Grade 12 results were 48% for maths, 53% for physics, and 66% for biology.

“I wasn’t really studying, I couldn’t really concentrate,” he says. “There was a lot going on when I was doing my matric. My mother passing away… and also the move from a rural school to the city where we were taught in English, everything in English.”

Cele came to study biology quite randomly. He applied to study at UKZN, only during October of his matric year – with admissions to most of the university’s courses having closed the previous month. He picked one of the last remaining options, biology.

Soon, the young student started excelling. Cele obtained his BSc Biomedical Sciences degree with a Dean’s commendation, and his Honours in Medical Microbiology, summa cum laude. He completed his Masters in Biochemistry with an upper class pass.

He said he would offer this advice to his younger self: “Do not be afraid, you are a force to be reckoned with.”

Cele’s driving passion is to advance public healthcare, which he will continue to do at the Aurum Institute – an organisation that, among other things, researches Africa’s tuberculosis and HIV response. Cele has a ten-year-old son who lives in Durban.

Note: The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is mentioned in this article. Spotlight receives funding from the foundation, but is editorially independent – an independence that its editors guard jealously. Spotlight is a member of the South African Press Council.

This article was published by Spotlight – health journalism in the public interest.

The merits of Dr Cele’s work aside, this one is for Spotlight and its declared editorial independence. By taking funding from the BMGF Spotlight is about as editorially independent as a 6-year-old at dinner whose parents tell them to jolly well eat what’s in front of them or go to bed hungry. Just like a sister health journalism platform of yours which routinely publishes in the DM, the majority of whose funding comes from the same source. And just like so many senior ‘health experts’ from the health faculty of a prominent South African university who have taken hundreds of millions in funding from the same source. Not to mention our national health products regulator. For any of these parties, yourselves included, to pretend an editorial independence you guard jealously would be laughable, were it not so perverse.

Hmm. To take it further, just like the BMGF billions in funding healthcare in the poorest regions of the world to treat millions suffering the harshest consequences of infectious diseases like AIDS and TB, providing access to reproductive health services for millions of women and improving life expectancy, or even funding to those grasping scientists deserving of your sneers who were funded by BMGF to run the trials of COVID vaccines that protected many millions in SA and around the world from severe morbidity and death.

Oh, just to say, we wouldn’t know about either the sterling work of Dr Cele (“The merits of Dr Cele’s work aside”, you say. Politically correct, much?) or the interventions elsewhere if not for focused healthcare journalism like Spotlight.

Without it, we may, like you, be languishing in the reactionary resentment arising from the efforts of these do-gooders like BMGF, right?

And, just to underline the importance of what you say, those women and those on lifesaving treatment may not quite understand your misgivings.

Perhaps you could try explaining it to them?