DESERVED RECOGNITION

Ezrom Legae and Sydney Kumalo: Art legends finally get their rightful due

A spectacular exhibition of sculptures by Sydney Kumalo and Ezrom Legae triggers memories of this writer’s first encounters with South Africa’s artistic achievements — as well as sadness that so much of the country’s art remains inaccessible to most of its people.

South African artists Ezrom Legae and Sydney Kumalo have finally got some real star treatment. Well, it is their sculptures and their posthumous reputations that are getting most of this attention. This is because both men died more than a generation ago (Kumalo in 1988 and Legae in 1999), but only after years of intense and very productive creativity.

For the past month, more than a hundred of their sculptures, as well as related drawings, have comprised a stunning exhibition at Strauss and Co in Johannesburg.

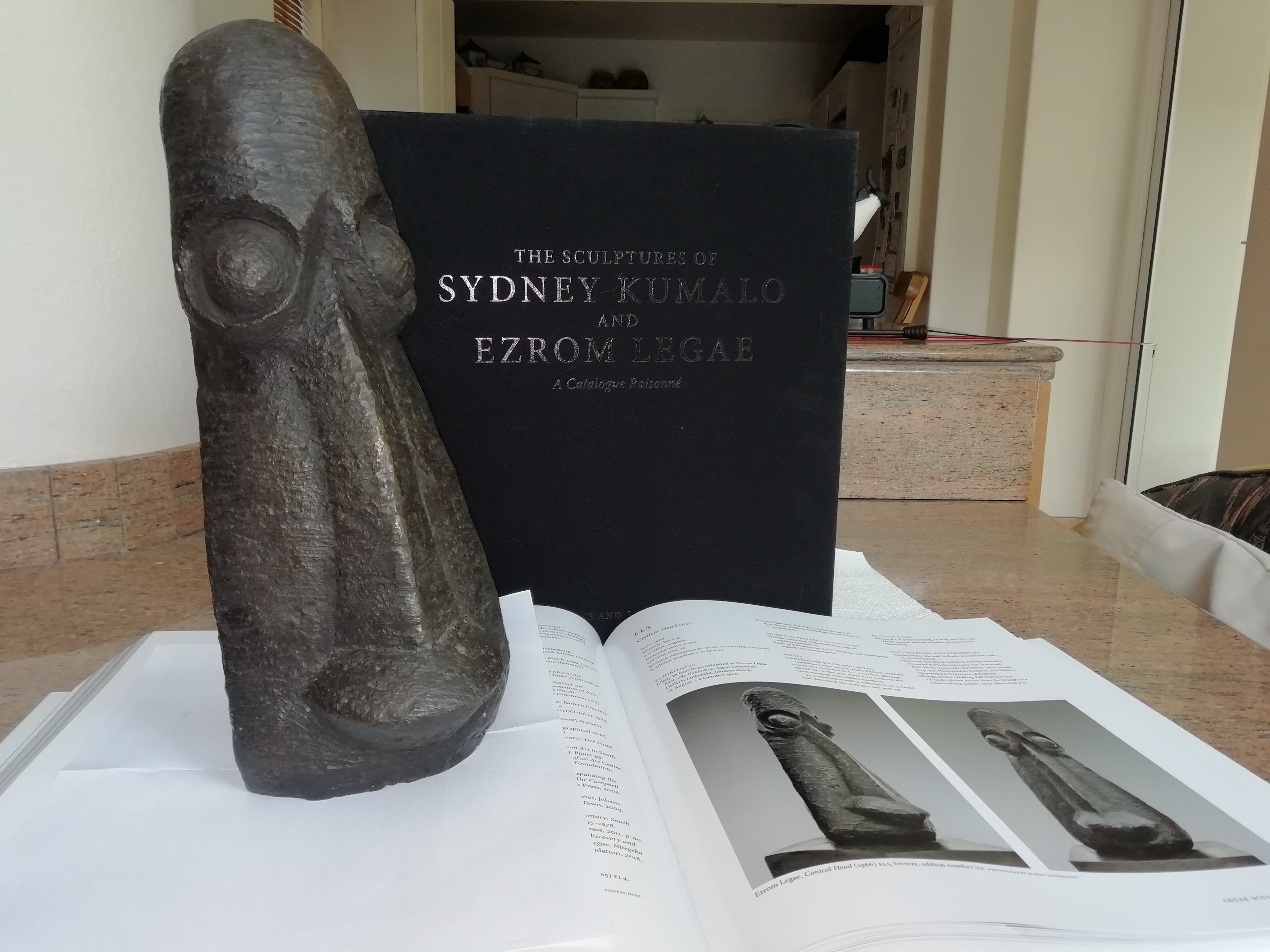

Ezrom Legae’s ‘Conical Head’, together with the new catalogue, in the author’s home. (Photo: Supplied)

This effort is quite different from Strauss’ usual run of shows in which items from private collections are up for “rehoming”. Instead, this joint Legae/Kumalo exhibition did not inspire the usual auction house fanfare designed to whip up the enthusiasm of potential bidders. Rather, it is a recognition of two of the most important South African artists of the 20th century — and thus a joint celebration of their creative energies and talents.

The show has been carefully, even lovingly, curated by Wilhelm van Rensburg and Arish Maharaj, in tandem with the release of a massive, authoritative catalogue by Gavin Watkins and Charles Skinner (collectors rather than art historians).

Authors of the catalogue, Gavin Watkins (right) and Charles Skinner. (Photo: Dave Woollacott)

Between them, as the result of several years of detective work, they tracked down the provenance of every known sculpture created by the artists and illustrated them along with information about the works in essays about the works, the artists and their times.

While the exhibition and book were still in the planning stages, we sat in our garden and talked with co-author Charles Skinner. I had placed one of Legae’s sculptures — a prized item in our own art collection — on the patio table. Our conversation led me to recall events that took place almost 50 years ago when this sculpture came into our possession and which now occupied an honoured place in our collection of South African art. (Over the years, we have lent it — and several other pieces — to South African embassies for exhibitions around the world, as well as to arts NGOs in South Africa for their exhibitions.)

At the beginning of January 1975, I arrived in South Africa as a young and inexperienced American foreign service officer. I was surprised to learn that besides the usual kinds of activities conducted by our offices around the world, such as running an up-to-date library, managing guest lecturer programmes on a range of topics and managing media relations for our embassy, our US Information Service office on Commissioner Street also organised art exhibitions in the auditorium.

On that first day in the office, I saw the latest exhibition as it was being taken down from the walls so the participating artists could retrieve their work (or make private arrangements with purchasers).

As the artists each came into the office, I met them and gained my initial sense of the ways our office connected with South Africa’s arts community, especially during apartheid’s heyday.

Then, a few weeks later, one of those artists, the sculptor Ezrom Legae, came into our office holding a brown paper bag under his arm, with something bulky inside it. Back in those days, there was no security presence at our office. People often just came in to go to the library or the film library, or they went straight to our offices — often without appointments. Black South Africans, especially, saw our offices as a very welcome “apartheid-free zone” in a racially oppressive Johannesburg.

Several smaller works by both sculptors. (Photo: Supplied)

Legae swept into my office and put the bag down on my desk with a bang; there was something heavy inside, but it clearly was not a bottle of spirits. He pulled out what was in the bag and placed it in the light streaming in on my desk, saying, “Do you want to buy this?”

“This” was a wonderfully strong yet deceptively simple bust of a stylised head in bronze, a man with protuberant eyes and lips that, when viewed next to its creator, revealed itself to be — to my eyes — a stylised self-portrait.

“How much?” I whispered. “Three hundred rand,” was the answer. I nodded, and without bothering to bargain, said, “Wait right here, have some coffee or tea. I’ll go right to the bank and draw the cash.”

In 1975, of course, there was no internet, no EFTs, and I suspected it might be a problem for a black man to casually cash my rather large cheque in the South Africa of that era. So I ran down the street to my bank branch, drew the necessary cash, raced back to the office and we exchanged money for sculpture.

Ezrom Legae’s sculpture, along with a work in pastel and charcoal by Winston Saoli, became the beginning of my fascination with contemporary black South African art.

In the succeeding years, Legae’s sculpture has travelled around the world and now resides, once again, in Johannesburg. This work, along with so many others, has been captured in Skinner and Watkins’ massive new volume, a catalogue raisonné, as such an effort is called, documenting the output of Legae and Kumalo.

The life of a black artist in South Africa back in the 1970s was usually a difficult journey and so the urge to create must have been extremely strong. Just obtaining those all-important passbook stamps and endorsements to reside in the Johannesburg area as an artist would be a problem since the accepted work categories for Africans for a coveted “10-1-A” stamp in a domestic passbook did not include “artist” or “sculptor”, and thus there were few spaces where they could freely practice their art.

Some artists found a way to be studio or shop assistants for kindly disposed gallery owners or dealers, or even, in a few cases, university laboratory assistants or assistant instructors in one of the few private art teaching institutions admitting black students, just as Legae and Kumalo did. But setting up their own independent studios would have been virtually impossible under the laws governing their lives in Johannesburg.

Very few artists, like Lucky Sibiya, found peace of mind and working space in a privately operated building. In his case, it was in the basement of the Anglican seminary in Hammanskraal, north of Pretoria. But for most, it remained a struggle.

Similarly, formal art studies at South Africa’s universities were also generally off-limits. What did exist, however, were a few privately organised art centres where established white artists like Cecil Skotnes and Larry Scully mentored younger, aspirant black artists.

Most prominent among these places were the Bantu Men’s Social Centre next to the equally important Dorkay House, and the Polly Street Centre that eventually became the Jubilee Centre. In the late 1970s, their prominence was succeeded by the Federated Union of Black Artists, an institution created by a collective of black writers and artists influenced by Black Consciousness thinking located in Newtown across from the Market Theatre.

Later, there would be the Johannesburg Art Foundation in Saxonwold near the zoo, headed by artist Bill Ainslie. And there was also the Funda Centre in Soweto, a project of the newly established Urban Foundation, a body set up in response to the Soweto Uprising.

In the years that followed, there were even some modest efforts supported by the apartheid government, projects such as the Mofolo and Katlehong Art Centres, as part of a response to the waves of protest beginning to engulf South Africa’s cities and townships.

Meanwhile, via a different impulse, missionaries from Europe had established an arts and craft centre at Rorke’s Drift in KwaZulu-Natal, at the site of a famous battle in the Anglo-Zulu conflict. There, artists from around the country came to study, work, and teach — and artists there created a thoroughly recognisable style for their work, but one that was different in its artistic sensibilities from the black urban aesthetic of many of the artists producing their work in and around Johannesburg.

By the middle of the 1980s, beyond exhibits at some commercial galleries for leading individuals such as Legae and Kumalo, exhibition professionals had curated several important shows of the works of contemporary black South African artists that simultaneously drew connections back to earlier artists and their efforts to produce works well beyond what was sometimes derisively referred to as genre “township art”.

The most important of these were Ricky Burnett’s “Tributaries” show in 1985 for BMW, and Stephen Sack’s “The Neglected Tradition” in 1988, the latter in the Johannesburg Art Gallery, still the city’s premier art venue. (By contrast, when I arrived in South Africa in 1975, that venue had only one work by an African artist hanging in its galleries — Gerard Sekoto’s “Yellow House”.)

More recently, into the 2000s, there have been exhibits that have highlighted the impact of African art on modern art, such as a major Picasso show hosted by Standard Bank and a showing of the Brenthurst collection of traditional African art. Additionally, Gerard Sekoto’s body of work finally received the attention it deserved via a major show in the new Wits Art Museum.

But already, back in the mid-1960s, both Legae and Kumalo had become well known as sculptors, and they were part of a loose collective of black and white artists called the Amadlozi group, or “the spirit of our ancestors”.

Amadlozi’s members initially included Kumalo, Cecily Sash, Cecil Skotnes, Edoardo Villa and Guiseppi Cattaneo, coming together under the encouragement of the noted gallery owner Egon Guenther.

Legae eventually joined Amadlozi as well.

As a commercial gallery operator, Guenther was already representing both Legae and Kumalo, although the two artists eventually moved to the Goodman Gallery later, a gallery that represented them both until their deaths.

Legae was already exhibiting his early works in the mid-1960s, including both drawings and sculptures, and by then his work was being added to private collections in South Africa and abroad. Then, in 1977, the death of Steve Biko hit him hard.

He stopped doing sculptures for a decade, although he continued to produce numerous drawings — many of them symbolically alluding to Biko and his agonies. By the last decade of his life, he had returned to sculpture, although his style had changed, moving away from his heretofore solid, dramatic — even monumental in miniature — forms, to a more articulated, more elongated style, instead.

In contrast, Kumalo’s sculptures demonstrated dynamism and plasticity even in bronze and terra cotta, a mix of attitudes observable in what is probably his most famous work, his African “St Francis”, in which the saint holds a dove in one hand, with his other hand outstretched heavenward.

Typically, his human forms were elongated and, as Strauss and Co described it, Kumalo presented “a diverse range of artistic expression which was daring in conception and a fusion of mythology and African culture”.

What is distressing about this magnificent exhibition — just like the earlier “Tributaries,” “The Neglected Tradition” and the Sekoto show — is that once the scheduled runs concluded, the assembled works were returned to their original owners across the world and never travelled throughout the nation to its other major cities.

The decay at the Johannesburg Art Gallery has also meant it is no longer a suitable venue for such shows and that its collection is under threat from pilfering and water damage.

Moreover, there is no national plan to celebrate the country’s great artists by creating and circulating exhibits of their works, let alone acquiring some of them for posterity for the nation if and when they come on to the market.

Instead, any such efforts have been left to private entrepreneurs to set up their own museums or fund special-purpose facilities at a few universities, but there is still no national effort to protect, preserve and share the wealth of the country’s artists.

Fortunately, this Kumalo/Legae exhibit will at least be featured in a documentary film to be available online, and some institutions may be able to purchase the catalogue for a more general readership. But that is insufficient to make such work available for all to see.

It is a great shame. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.