HEALING MEMORIES OP-ED

Father Michael Lapsley: ‘To the person who sent the letter bomb, I am grateful for what you’ve given me’

Father Michael Lapsley, who lost both his hands 33 years ago when a letter bomb sent to him by the apartheid regime exploded, celebrated 50 years in the priesthood on 1 July this year. He explains what the achievement means to him.

I arrange to speak with Father Michael Lapsley – we used to be colleagues on the staff of St George’s Cathedral in Cape Town – by Zoom on a recent Saturday afternoon. He is slightly late. “Please forgive me,” he says, “I’ve been napping after the longest funeral ever” – an over-three-hour marathon for another colleague. As he wakens himself, he waves his prosthetic limbs enthusiastically towards me.

To those who encounter Fr Michael for the first time, his prosthetics can be somewhat disconcerting. It’s not the look of them. It’s what to do in response to meeting.

“I can’t shake hands,” I remember him saying to me the first time we met in 1996, as the first biography of him by Michael Worsnip, Priest and Partisan, was being launched six years after a letter bomb – almost certainly sent by the then South African apartheid government – tore into his body and literally blew off his hands as he opened the parcel. “I can’t shake hands,” he had reiterated, “but I do love hugs!”

I’m sitting in Oxford as we meet – where I was long ago a student – and the memories of the place and the people I met in those formative years – mid-1980s, the height of the anti-apartheid struggle when I played a small part as a student activist to bring down the South African government – remind me that I used to discuss this and much else when I went to read to another Michael, Michael Ramsey, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, then resident at a nursing home in Cowley.

I remember him recounting excitedly one day that he’d been to buy a newspaper that morning and that the Muslim shopkeeper had asked him for how long he’d been a priest. He had replied that he’d been ordained for more than 50 years. And the shopkeeper had immediately responded, “That’s a very long friendship.”

So I use this memory to initiate our conversation and to prompt Fr Michael to reflect on what he will most be feeling and thinking as he celebrates his golden jubilee in St George’s Cathedral. He responds that, as he’s been preparing for the mass of celebration, he’s realised the cathedral has been his base for 32 and that it’s been an anchor for him.

He hasn’t always been physically present, of course, as the ministry of healing and reconciliation that followed the horror of the Harare letter bomb – he was working for the ANC in exile in Zimbabwe at the time – has, for example, seen him lead thousands of weekend retreats for those, like him, needing to work through, even transfigure, their own experiences of pain and trauma.

But if he hasn’t always himself been there at Sunday Mass, his spiritual presence has nonetheless been considerable and utterly transfiguring for this, as for so many communities.

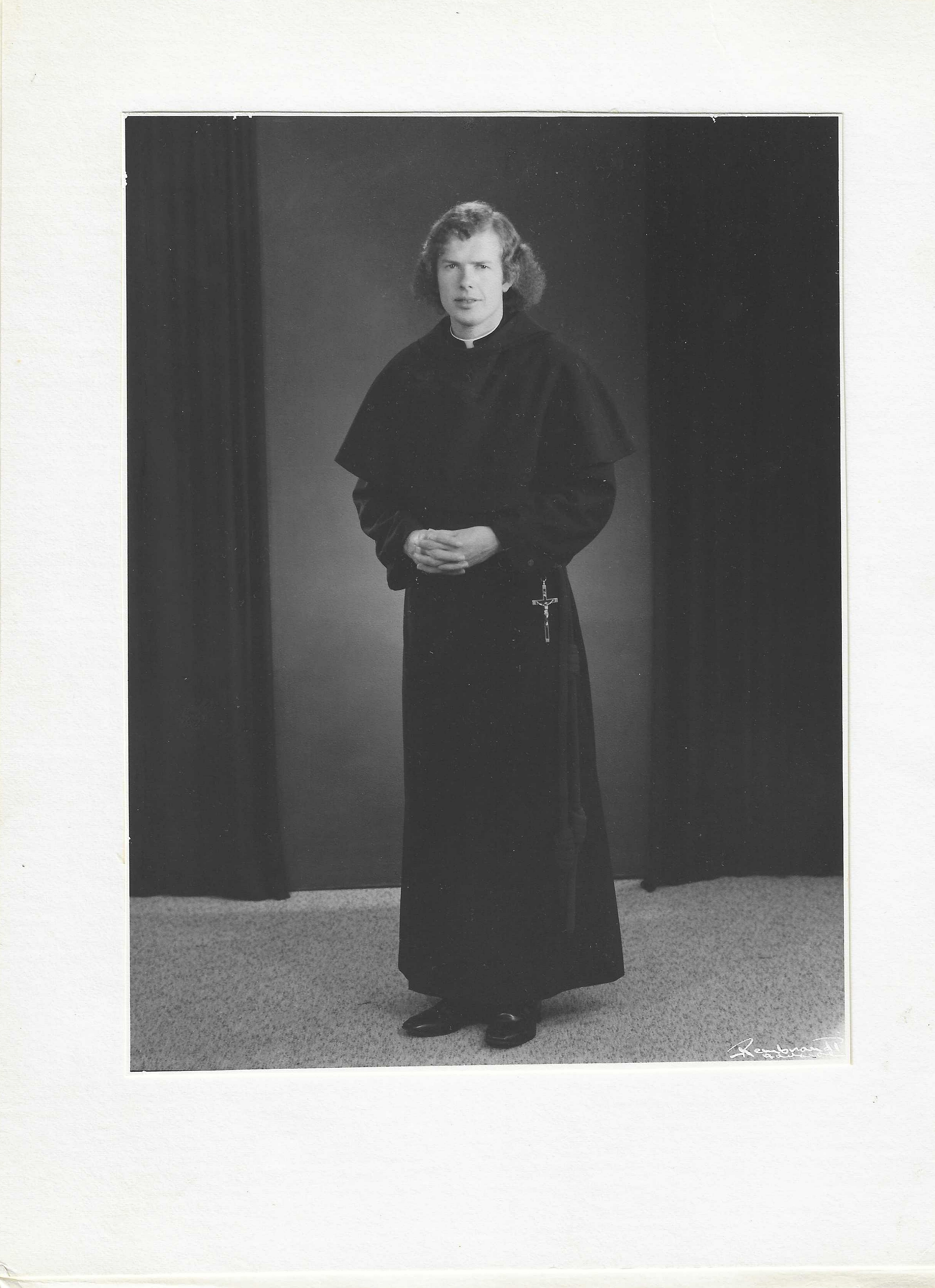

Father Michael Lapsley today, 33 years after he was seriously wounded when a letter bomb sent to him by the apartheid regime exploded. (Picture: Supplied)

‘Another baptism’

“My main feeling will be one of immense gratitude,” he reflects. “But I’ve also been thinking about where does being bombed fit into this. Part of me wonders: was that another baptism, an ordination?”

He explains that he has been thinking about the South African martyr Manche Masemola, who is among the statues of the 10 20th-century martyrs on the front of Westminster Abbey and who was killed by her own parents for converting to Christianity – her mother, and murderer, herself later being converted and baptised by the then bishop of Natal, Michael Nuttall, a mutual friend who preached so memorably at Desmond Tutu’s funeral.

Manche Masemola had known the risks of conversion. She famously talked about her baptism “being in her own blood”. In quoting this to the new young brothers of the Society of the Sacred Mission (SSM) in Lesotho, a few days before we spoke, Michael has evidently been prompted to wonder whether, beyond his own rather conventional baptism in water as a baby, “the bombing wasn’t a baptism in my own blood”.

It’s a most extraordinary image and assertion. Almost impossible to explore further in a conversation of this kind. It’s the sort of image with which one simply has to live for some time, somehow inhabiting it in order to begin to grasp something of its deeper significance.

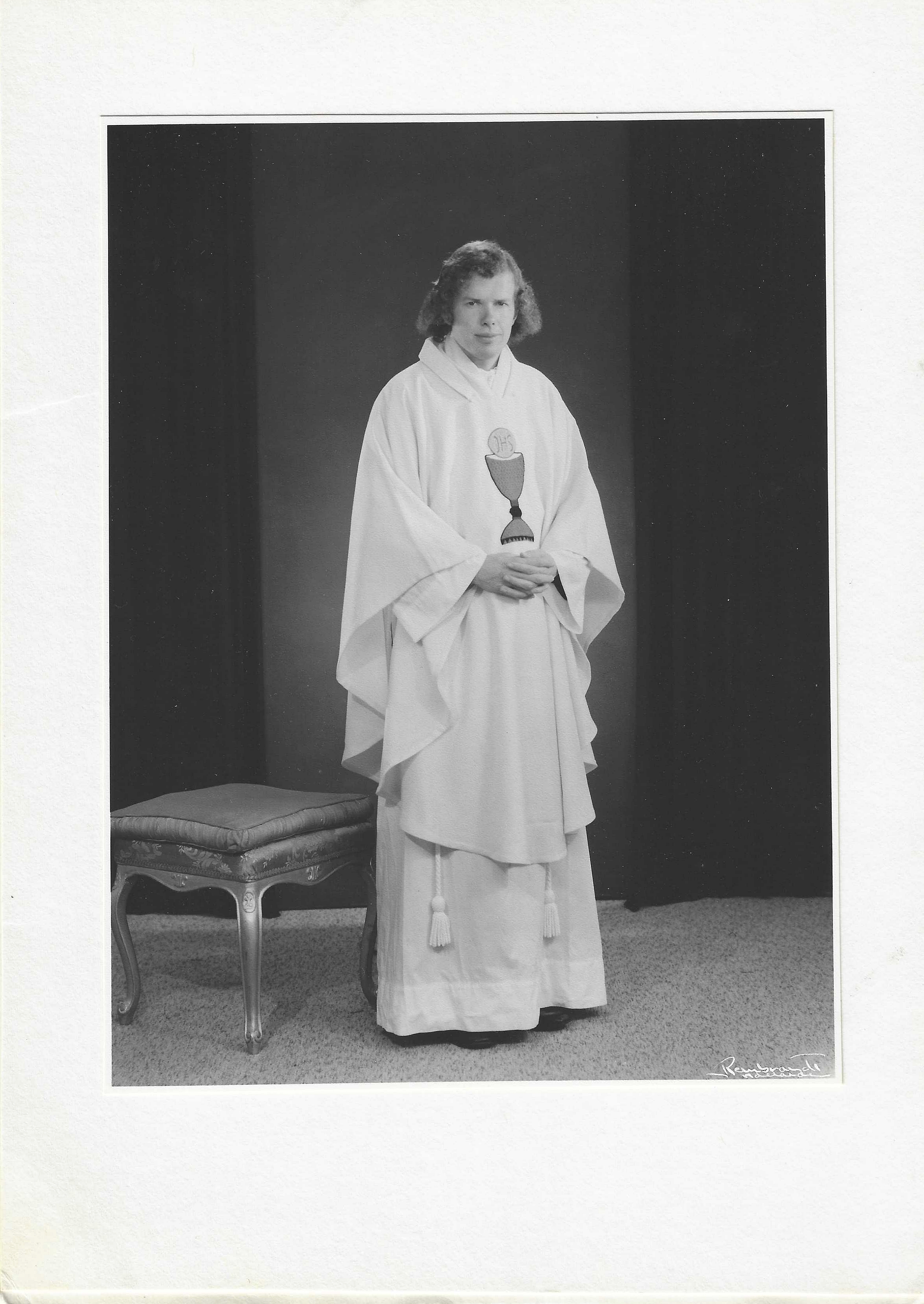

But alongside it, I set for Michael the image that has always struck me most about him. It’s for me indeed become both emblematic and iconic. It’s the image of his prosthetic limbs elevating the host during the Mass. It’s as close in this life as I think I will ever come to sensing the risen Christ who bears the wounds of his suffering in his own transfigured body.

I realise I am not the only person to have sensed this reality in Michael as Eucharistic celebrant. Doubtless it’s certainly an intimation too elevated for any priest to claim for themselves. And Michael would be the last to do so. But whatever he thinks of my attempt to articulate what I’ve felt seeing him so often at the altar, he earths the image in his own story.

“Two days after I received the letter bomb in April 1990 I was to have been instituted as a parish priest in Bulawayo. The person who was to have been my bishop prayed for me before I was transferred from the hospital in Harare to one in Australia.”

Seven months and several complex operations later, Fr Michael returned. He met the bishop and said, “Here I am!” The bishop looked shocked and confused, Michael explains. By this time he had given the parish to someone else. “He clearly didn’t quite know what to say,” Michael continues, dispassionately recounting what happened next. “He looked at me and said, ‘But you are disabled now. What can you do?’”

As Michael recalls what must have been a shocking and immensely challenging moment for him, I am watching him intently. I do not detect a hint of anger, even a flicker of frustration. I can only see such compassion in his eyes and hear such love in his voice that in this very moment my own increasing irritation in relation to this thoughtless prelate is completely transformed.

“I said to him,” Michael recounts with what must be hard-won calmness and grace, “I think I can be more of a priest with no hands than I ever was with two hands,” adding with great gentleness, “the bishop wasn’t a bad man. It was just all beyond his imagination.”

I pause internally to soak in this pearl of wisdom – there is always after all so much that is beyond our imagining until we give ourselves space to rethink and to change – before Michael sets this bishop alongside our mutual friend, the late Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who, by contrast, immediately asserted, “I have a priest who’s deaf, one who’s blind, now one with no hands, come and work in my diocese. Wow!”

As Michael repeats the words one can almost hear the sparkle of the Tutu voice, his own hands – like Michael’s prosthetic limbs – always upraised in open and animated welcome.

The idea that “being a priest means to be able-bodied” is, Michael suggests, entrenched in a traditional theology that “to be a priest is also to be a real man”. Michael confounds this and it is clear that a strong part of the gratitude he feels at this moment of jubilee comes from the “recognition that I can travel anywhere in the world and no one says to me, but you don’t know suffering, you don’t know pain”.

‘Instant connection’

He has just returned from South Sudan which has, Michael explains, had 40 years of war “with levels and levels of loss and grief and pain”. But because of what has happened in Michael’s life there is, he opines, “an instant connection. I haven’t,” he suggests, “had their particular experience but in grief and loss I’ve discovered that pain is transcendent, it becomes a passport to connect.”

This has of course become the heart of Michael’s amazing ministry. This has emerged from his founding of the Institute for the Healing of Memories in South Africa, to sit alongside the state-instituted attempt in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission post-apartheid – chaired so memorably of course by Tutu – to bring healing and hope to a South Africa reborn as a democracy, and seeking to entrench a culture of human rights and human dignity.

Fr Michael is at pains to emphasise his rootedness in this southern African experience and his gratitude for it. But equally he recognises that he has always been rooted in his religious community. “They chose me. They sent me here. My job was to obey them,” he states emphatically. And indeed, born in New Zealand, trained in Australia, it was his community who sent him to southern Africa, a call which has led him to have to transcend personal pain at a level few could imagine.

I suggest that this ministry has made him a global priest with the widest parish and he readily agrees. I pick up an earlier strand and suggest he has embodied for each of us a Christlikeness that has enabled people to identify with him, and that on this much of this global ministry depends. But he is at pains again to point away from himself and to root this in the tradition, in God.

“Remember those words of St Paul,” he says, “Three times I asked for the thorn in the flesh to be removed from me. But God says my grace is sufficient for you.” He chuckles as he continues, “Unfortunately one’s messed-upness as a human being doesn’t get taken away. As anyone you stay with will tell you. You think you are this and this and this. We can tell a few stories about you. The fullness of one’s humanity and brokenness is part of you, but that’s where one can be a help to people. A plaster saint is of no use but a messed-up human being who is able to experience grace is able to become a real role model with whom people can identify.”

No sooner has Michael suggested this about himself than he immediately subverts it again. “When I was four years old, I couldn’t decide whether I wanted to become a clown or a priest. When I was ordained a priest, my brother sent me a telegram and said, ‘Now you’ve succeeded at both’.”

The clown figure is the figure of humour and the court jester who can say rude things. I suggest to Michael he has played both these roles in speaking truth to power, as much within the church as within society.

He agrees this has been a “lonely road”, recounting a story that, after he received the letter bomb, “Seven of the primates of the Anglican Communion wrote to me, for which I will always be grateful. But they weren’t of course about to write to me for being a freedom fighter.”

The institution was comfortable with the language of martyrdom – they were content to express and indeed project a reality they thought they could understand, but in truth could never do so onto an individual sufferer – but seemed less responsive to the God who overturns the tables in the temple and directly challenges politically unjust structures.

“We are more comfortable,” Michael suggests, “with the one who has become a victim than the one who wants to live out a commitment to justice.”

My very first encounter with Michael was through reading his book that emerged from the Zimbabwean struggle for freedom, Neutrality or Co-option (1986), an at times swingeing critique of the inadequacies of the role that the churches played in relation to the liberation movement and certainly as strong a statement of freedom fighter intent as one might recall from a Christian writer in the 1980s.

This inspired me in my own journey – which also took me through the anti-apartheid movement to ministry in South Africa – and enables our conversation to take a turn towards the contemporary challenge for any priest-advocate for justice. What, I wonder, does he think is the biggest of these right now?

Michael, like so many of us, continues to draw inspiration from Tutu. He suggests that Tutu could simply have become “a black nationalist fighting for freedom”, but went on to “fight for women, for LGBTQI+ rights, to champion the pain of Mother Earth, to criticise the democratic government in South Africa, and to recall the liberation movement to its core values when it lost its way”.

He is clearly alluding to the way in which his own ministry has mirrored that of his mentor and friend. But, in so doing, he is also pointing to the way in which the liberation movement in the 1980s expected Michael to be more than a freedom fighter.

“I often wanted to downplay that I was a priest. I’d say I’m just a member of the ANC. But they wanted me to be a pastor, to walk alongside, to accompany them. They’d say sorry, you can’t be just another member. We expect you to be a priest for us.”

This again returns us to John Wesley’s “the world is my parish”. “I’m a Kiwi boy,” Michael summarises, “Australian-trained, who became a South African, and then an internationalist. In Christ there is neither Jew nor Greek. Male nor female. Slave nor free. Just one new creation glorious in its human diversity.”

He began the healing of memories methodology in South Africa 25 years ago and is now the president of a movement that is truly global. He is a religious leader known the world over.

When I ask him what roots him still, he enthusiastically shouts back straight away, “Richard Rohr.” He is an assiduous follower of the latter’s daily online meditations. “I’m fed profoundly by his spirituality, but perhaps even more so by the story or prayer for our community with which each meditation ends.”

Michael suggests he’s also often most moved by reactions he reads from people who have found in these stories or prayers something which resonates deeply with their own communities. It’s also prayer and the rawness of human narrative and experience that he loves when people come forward at the end of Mass in the cathedral in Cape Town or that in Alberta, Canada – in respect of both of which he is the canon for healing and reconciliation – to express particular healing needs or to ask for prayer.

Alongside these personal desires for healing, Michael sets the challenge of “Mother Earth who weeps, who is wounded by us. The amount of money spent on arms. I’m sure God weeps for that. Or the moral blindness of the whole world focussed on Russia and Ukraine … but what of the pain of the Palestinian people or the people of Myanmar whom I know so well?”

He very much feels the “pain of the forgotten people of the world”. He longs for a new peace movement and for healing of what he describes as “the longest wound of the human family … how women have been treated”. He suggests deepening consciousness about ending patriarchy “will not only liberate women but liberate men”. Fundamentally “seeing people as people” is the truth we most need to embrace.

In such a global and expansive view – which seeks to celebrate diversity and always to extend further its embrace – I venture to wonder whether there is room for thoughts more personal at his Golden Jubilee Mass? As if he is holding William Blake’s golden string in his hand winding it into the ball that leads to heaven’s door, he returns to the theme of gratitude. But with a twist I had not expected – though should have done.

‘Profoundly grateful’

“I was meant to have been killed. That was the intention. Now 33 years later I’m able to celebrate the 50th anniversary of my priesthood, wanting to say to the person who sent the bomb, I am so grateful for what you’ve given me. I pray for you but I’m profoundly grateful for what you have given me.”

It’s a moment that takes my breath away. Again, subverting, pointing away from his own story, he turns to some words of Thomas Merton. “Merton,” he recalls, “says something to the effect that he’d taken his monastic vows but that he was not yet a monk. Similarly, I’ve been ordained a priest but I’ve not yet become a priest.”

He reminds me that, in the South African liturgy, as they elevate the host, priests often now speak the invitation to Communion, “Behold who we are: may we become what we receive.” This seems to encapsulate the journey of becoming to which Michael has directed attention throughout our conversation.

We are back with the image of Michael, his prosthetic hands elevating the host, the risen Christ bearing the transfigured scars of his suffering. I can think of few priests who could have made such a deep and defining contribution to the human journey of becoming, at such cost, with such humility or with such humour.

Like many others, I certainly expressed my own gratitude to God for Michael on 1 July as I returned with awe and wonder to the Christlike generosity he consistently shows and that has seen him able even to make the person who sent the letter bomb that so maimed him part of his – indeed, part of our – becoming. DM

Chris Chivers teaches religion and philosophy at UCL Academy, London. He was formerly canon precentor of St George’s Cathedral, Cape Town.

Like so many others, I AM Grateful for the many teachings we receive during our Journey on Earth.

This beautifully written article brings back such memories of the bomb sent to Father Michael in Zimbabwe … 33 years ago:

The number of years Jesus spent on earth teaching love, peace and the power of Forgiveness. Like Father Michael.

Reading about Manche Masemola is very inspiring. And heart breaking too, as a loving parent. Her initials MM, like Mother Mary.

Thank you Chris for your words of Wisdom. I AM grateful.