BOOK EXTRACT

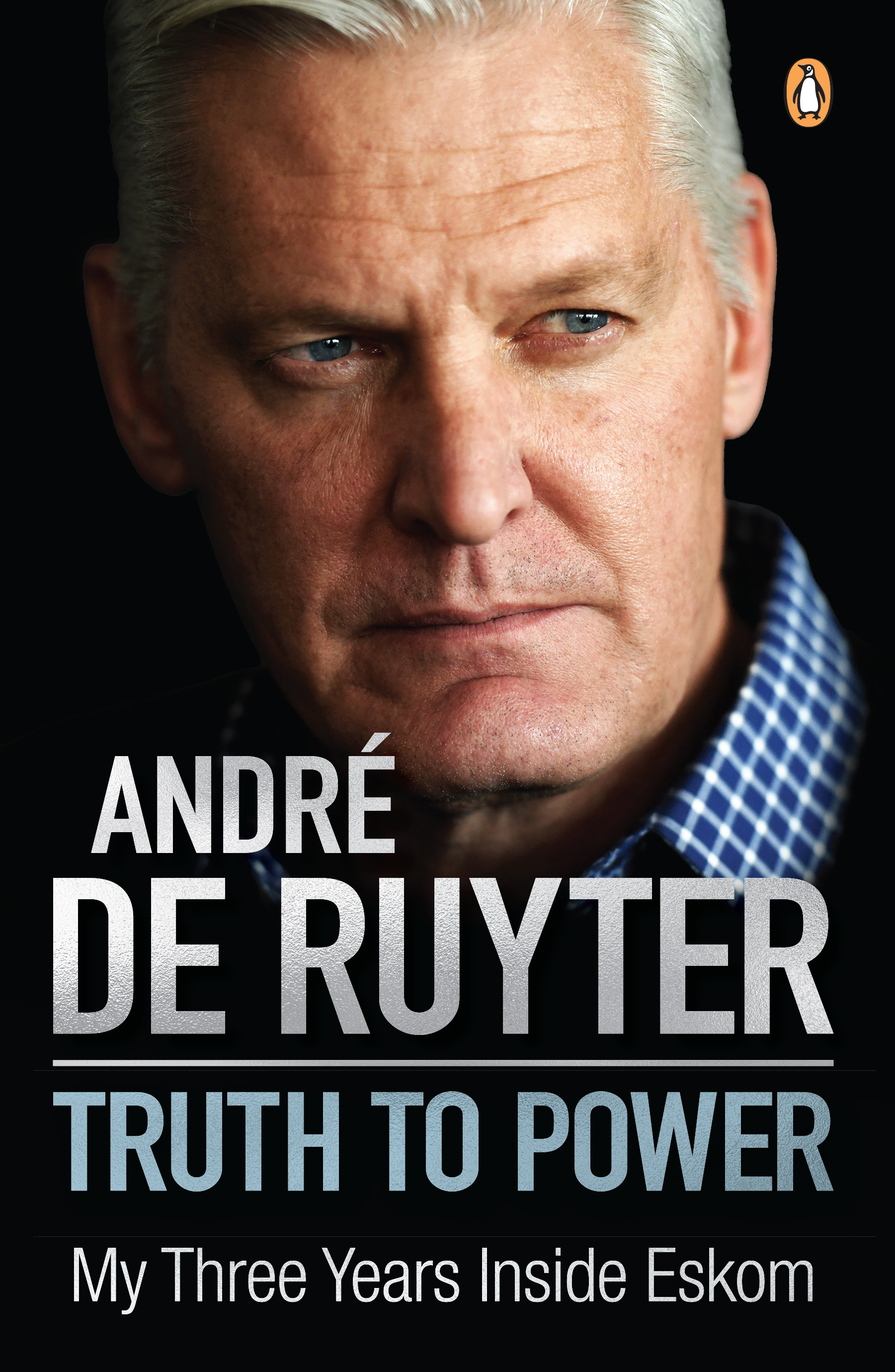

André de Ruyter’s Truth to Power: The bombshell information uncovered by private intelligence

This section of former Eskom boss André de Ruyter’s memoir of his time at Eskom sets out the circumstances in which an intelligence-gathering exercise was funded and implemented to probe sabotage at Eskom. De Ruyter details in his book how the investigation started and how it was catalysed. He details police inaction on reports made to them, which led to the commissioning of private intelligence. He speaks highly of the National Prosecuting Authority director Shamila Batohi’s efforts to investigate and prosecute the sabotage that is a factor in what he says are one or two stages of load shedding. This is an edited version of that chapter.

Although I am not privy to the exact financial details, I’ve surmised that the total cost of the investigation ran to approximately R3-million per month. The informants were also compensated from these funds.

It didn’t take long for the investigators to uncover bombshell information.

(Image: Supplied)

They identified no fewer than four criminal cartels exploiting Eskom. These cartels had their own identities: the Presidential Cartel was led by a supercar-loving gent, with a host of companies to his name, and focused on Matla power station outside Kriel. The Mesh-Kings Cartel operated out of Witbank, with Duvha under its control, and also had its own favoured corporate entities to funnel money out of Eskom. The Legendaries Cartel, which had Tutuka in its grip, was based in Standerton, where they operated businesses with contracts with Eskom, suppliers and local structures. Their members were embedded firmly in political structures in the town, and higher up in Mpumalanga. The Chief Cartel operated out of Newcastle, and thus had domain over Majuba, with a focus on coal supply by road. Again, there were close ties to politically connected individuals. Other cartels are said to be operating elsewhere, and are in the process of being uncovered.

Like any good organised crime structure, the cartels have delineated their areas of operation, and generally get along without overt conflict. They have ‘soldiers’, a term familiar to anyone with a predilection for mafia movies.

And tribute gets paid to higher structures, so that the capo dei capi can secure his share of the revenue stream. The modus operandi is pretty standard, almost as though there is a communal exchange of ideas in pursuit of excellence in crime.

The cartel leader or his subordinates typically approach a specific end-user, who could be an Eskom engineer or manager, to begin the illicit process. The end-user, who is authorised by the Eskom delegation of authority to place orders on the procurement system, creates a fictitious demand for goods or services, with the purpose of defrauding Eskom. He receives a substantial amount in cash, including extra funds to pay an upfront bribe to a key store official at the power station.

The store official then verifies how much of a specific type of equipment is available on inventory to be covered in a purchase order. Should the equipment to the value of the intended purchase order be available in stock, the existing equipment in stock will be hidden or displaced somewhere in the power station to justify the purchase request.

Next, the end-user approaches the procurement contact, or an employee referred to as an mphati who works in collusion with the cartel and is an influential contact at the power station. The procurement official receives an upfront inducement that serves as an acceleration fee to facilitate a purchase request. The illicit procurement process is set in motion. The procurement official arranges for the financial department to approve the expenditure that must, according to Eskom’s supply chain directives, have the signatures of both the end-user and the store manager.

The purchase request is then taken to a senior buyer who will receive their share of the bribe. After that, three compulsory quotes are obtained – ostensibly to ensure competition. But it is all a sham. The process is rigged so that all three quotations originate from the same cartel.

The vendors manipulate the quotations so that a specific pre-chosen company is inevitably appointed as the supplier, and a purchase order is issued accordingly. In addition, the buyers often create a false sense of urgency by sending official emails to the vendor to expedite delivery, which will then be used to justify a higher price.

Once the order is ready, the cartel, through the appointed vendor, arranges for delivery during a specific security shift at a particular time. A vehicle with a ghost delivery arrives at the power station gate. The security guard, an accomplice who is paid for his services, signs the delivery note and verifies that the equipment was inspected at the main gate.

The end-user and store official purport to receive the ghost delivery and sign the receipt for the non-existent equipment. The hidden equipment is retrieved from where it was concealed and placed back into storage as if the new equipment had been delivered. There is no link to the actual requirements of the power station – making it clear how billions of rands of inventory could be accumulated at each power station, with no hope of the spares ever being used.

All the procurement documentation from the purchase request to the delivery note will procedurally correspond with the equipment on inventory, making it difficult for forensic audits to identify fraudulent practices except by doing a physical stock count, a discipline that had also been left to wither as the floodgates of corruption opened.

The acceleration fee to the mphati or procurement official ensures that payment to the cartel is made within one week instead of the usual thirty days. This procurement process is repeated at various power stations and amounts to millions of rands of fraudulent transactions per month per power station. Easy money, and very difficult to detect.

Upon receiving payment from Eskom, the vendor or soldier who owns the ghost company that successfully tendered for the business retains his allowed portion of the money and delivers the bulk of the funds to the leader of the cartel. The leader retains his allowed portion, and the balance is handed to a trusted intermediary who also receives a portion for services rendered. The intermediary then delivers the rest of the money to the obscure initiators.

No wonder that measures to implement controls – better use of SAP, barcoding, inventory controls, outsourcing of procurement – are actively resisted and undermined, even at Megawatt Park. Time and time again, goods and services are procured outside of group contracts that are supposed to leverage Eskom’s buying power. Instead, the usual three unknown local companies are approached for bids outside of the contract.

The geese that lay these golden eggs must be protected, after all.

To create a supplementary business to supply essential components or to renew or continue maintenance contract works, the cartels also collude with insiders to ensure the destruction of equipment such as conveyor belts and gearboxes. The breakdown is then used to justify repairs or the supply of components via the cartel vendors.

In addition, the cartels are involved in the sabotage of railway lines feeding power stations to ensure the survival of their trucking companies that transport coal to Eskom. The damage they cause to the country is of little concern to these criminals.

It’s clear that the coal value chain is uniquely lucrative for the cartels – which must at least be part of the intransigent resistance to renewable energy. Sun and wind are much more difficult to steal.

One of the cartels had a ‘hit squad’ consisting of sixty members, while another had a so-called ‘seductress’ in their employ. Her love nest had an urn standing in the corner where ‘offerings to the ancestors’ could apparently be made. A certain car dealership in the coal belt specialised in housing fancy vehicles on behalf of their owners so that they didn’t show up in lifestyle audits. The vehicles, always held in the name of the dealership, would be available on demand, should the actual owner wish to take his Lamborghini for a spin on the potholed roads of Mpumalanga. The banal decadence was shocking. As Jan often remarked, ‘Greed is an incurable disease.’

The investigators mapped out the links within the cartels on a huge diagram that we termed the ‘building plan’. It consisted of the full names of the cartel members, as well as personal information such as cellphone numbers and, if possible, a picture.

The cartel members revelled in displays of obscene wealth, sometimes washing their hands in fifteen-year-old whisky to show that money was no object.

The informants included employees of Eskom and members of the criminal networks. One power station employee, who is also a union leader, claimed that orders to trip units came directly from Megawatt Park. At the time of writing, this allegation was still being probed but it squared with the information that had sparked the investigation in the first place, namely that plant breakdowns were often orchestrated in order to precipitate load shedding.

By far the most explosive aspect of the investigation was the intelligence that started to emerge that the Eskom crime syndicates potentially stretched right into the upper echelons of the political establishment, with two senior politicians said to be ultimately benefiting from the corruption through a web of interlinked interests. I have decided against naming them publicly at this stage, or giving too much detail away, as the investigation was still under way at the time of writing.

Many of the investigators’ findings offered an explanation for some of our operational struggles. Poor-quality coal, for example, was a huge issue at most of our power stations. Following a tip-off I had received, the investigators uncovered a ‘coal mafia’ that was operating in our northern provinces. It was in cahoots with transport companies. After the good-quality coal was dispatched from the mine, the truck driver would go to a so-called ‘dark site’ where he would swap his load for low-quality discard coal. The discard may have had a lump of coal here and there but was not much better than rock, wreaking havoc with our boilers and coal mills when we tried to burn it.

The good stuff remaining at the dark site could then be resold or exported, creating stratospheric profits.

One modus operandi of this criminal network was to sabotage the conveyor belts taking coal directly from a mine to a power station. This would ensure that the coal had to be transported by road, translating to higher profits for trucking companies – and, of course, more opportunities for corruption by dumping the coal at the dark sites.

The person who gave me the original tip-off was terrified for his safety. ‘If they find out I’m talking to you, they will kill me,’ he said.

At times, it felt like we were engaged in low-grade civil war against criminals threatening to overrun the state. This was no normal turnaround job.

When we eventually shared some of our findings with the SSA, they were blown away by the information, which was an indictment of the state’s own intelligence-gathering. I wanted to say: You are the State Security Agency. How can you be so oblivious as to what is going on in the energy heartland of South Africa? DM

André de Ruyter: Truth to Power – My Three Years Inside Eskom; published by Penguin, Random House, 2023.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

But of course the corruption goes all the way to the ‘top’. My only doubt is whether it is limited to two persons at that level.

*Gobsmacked*. I didn’t think it was possible, but this sounds even worse than I imagined. Oh, if only those in power ran the country as successfully as they run their criminal enterprises! SA would be sorted. I hope de Ruyter is staying safe and that the names of the capo dei capi are ultimately revealed for prosecution.

But in my head, I thought much the congratulated dep prez Mabuza and Gwede-the-planet-destroyer had already been identified as the top crooks that Cyril couldn’t censor until proven (by SAPS, what an unfunny joke!). And I thought I got that from DM reports! But surely NPA is chasing lifestyle audits, at least on them, if not Cyril too. None of what I’ve read is a surprise. Civil war is a good way to describe it. Why else is the ANC visiting fascist Putin? The ANC is the enemy of the people of SA. That’s not saying DA or any other party is our friend. Just saying civil war with our backs against a fascist cabal will not be pretty.

This all is very credible. I used to work for a coal company and my ex colleagues who are still active can pinpoint these coal transfer yards. It is impossible to practice good quality control on coal coming in by truck whereas when coal was delivered by conveyor from tied collieries, there were stringent effective controls and sampling. Unfortunately, due to Jacques Paauw’s exposure, this report is now largely discredited due to an apartheid era hit man’s involvement. I suspect that this storm will blow over and everything will be swept under the carpet and corruption will continue as usual.

“it felt like we were engaged in low-grade civil war against criminals”.

I think us South Africans must now know we are in fact in a civil war.

Surely these ‘spares’ need to be manufactured somewhere , so if my company X is required to supply spares then I would need a factory to manufacture them or to buy off a factory that makes them … at some point something ‘real’ would need to be made – if the ‘spares’ are just being hidden then re-appear wouldn’t it be possible to go back to the manufacturer to see if the spares were actually made and look for invoices for their manufacture – follow that chain …. SARS checks my materials invoices when I make something to find my profit and tax me accordingly … if they were never actually manufactured then logic would say there would be no proof of the materials used in the manufacture or for that matter a factory producing these fake spares …. go to the source and check

With all this information from the investigation, why is the NPA not been given the information and power so that the various people, from top to bottom, can be charged and prosecuted. One can only presume they are being protected by the corrupt politicians at the top. One can also hope the Gordham stops protecting the corrupt persons and names them in his meeting with Scopa today

This is not “rent seeking”. It is treason.

Yes, but does anyone at Luthuli House actually care?

How can a government this corrupt, this deferent of conscience still get (along with their bastard child the eff) still convince more than 50% of the population that they are the right choice to vote for?

How can a people be so willing to NOT believe that voting for the exact opposite of what they are getting will bring them the exact opposite of what they are getting.

Because they do not know. It is convenient for the ANC to keep education at a level where the average citizen does not have the ability to think critically and ask awkward questions.

The ANC has spent as much time distancing themselves from being the government in charge while trumpeting that they are the only ‘revolutionary party fighting colonialism’ and that they are the only ones standing in the way of ‘the government’ taking the little welfare they have away.

As Zuma said “Clever blacks are a scourge upon the continent”. As @TracyMcGahey points out our education system is ensuring that “clever” for the vast majority of the population will never happen!

It’s mind boggling what these parasites who call themselves ministers have done to this countries economy. I have been in RSA for the last 50 years and I have never heard of any other country that had a corrupt Government as bad as the ANC. Yes Zimbabwe was corrupt under Mugabe but nowhere close to what the ANC are doing. I really hope the DA get into power then round up all the looters and charge them in a court of law.

It’s mind boggling what these parasites who call themselves ministers have done to this countries economy. I have been in RSA for the last 50 years and I have never heard of any other country that had a corrupt Government as bad as the ANC. Yes Zimbabwe was corrupt under Mugabe but nowhere close to what the ANC are doing. I really hope the DA get into power then round up all the looters and charge them in a court of law.