ESCAPE

War in the Karoo Heartland

Many years ago, in the snowy drifts of a deep Karoo winter up near the Wapadsberg between Graaff-Reinet and Cradock, I found evidence of a murder most foul.

My old mate Ryno Ferreira and I were tooling around the back roads on snow business in his venerable Land Rover Defender, looking for seasonal photographs and finding landscapes in stark black and white. Everywhere we turned, the scenery had been transformed into a never-ending series of gigantic Japanese line drawings.

For a brief, teasing moment, the weak August sun emerged and made the streams sparkle, adding deep texture to the ancient sheds we passed and an elegant silkiness to the mountain slopes all around.

Farm graveyards in the Karoo tell so many stories, but you have to scratch a bit, dig deeper, ask questions, link reports and discount rumours to be able to unearth them. So when we stopped at a little family graveyard in the spectral snowscape, it was more in the hope of cadging a scenic photograph than finding a treasure of a tale.

The grave of Hendrik van Heerden, executed on his own farm in the Karoo Heartland. Image: Chris Marais

Part of the Sneeuberg range in winter, when the dolerite ramparts resemble one of the sets of the Game of Thrones series. Image: Chris Marais

One particular grave drew us nearer. It consisted of a lichen-bedecked, sandstone base with a marble inset, one which read (translated from the original Dutch):

“In Memory of H.J van Heerden, Born November 9, 1866 in Cradock, wounded on March 1, 1901; shot dead without a hearing on March 2, 1901 at Zevenfontein, Middelburg.”

That inscription was followed by a biblical reference and at the bottom it read:

“Placed by friends.”

After taking our photographs and speculating on the story behind this sad little scene, we climbed into the Landy and drove on. I could not, however, get the lonely gravestone out of my head.

The Middelburg historian

And so it was with great joy some months later that I met Hennie Coetzee, the author-historian from Middelburg, who had just published a large book on his home town and surrounding district. I mentioned finding the Van Heerden gravesite and he immediately directed me to Page 233 of his well-researched Middelburg, Hede en Verlede (Middelburg, Present and Past).

The view of the Karoo Heartland from above the Valley of Desolation. Image: Chris Marais

Graaff-Reinet – under occupation by the Coldstream Guards during the latter half of the Anglo-Boer (South African) War. Image: Chris Marais

“What availe (sic) it a man that he gain the whole world but lose his own soul.” – a biblical quote on Oukop overlooking Cradock, said to be the handiwork of a British soldier. Image: Chris Marais

There was the official story of Hendrik Jacobus van Heerden who, even though he was a non-combatant, found himself fatally involved with the Second Anglo-Boer War:

“On March 1, 1901, members of General Kritzinger’s commando arrived at Zewenfontein Farm and asked for some food and fodder for their horses.

“Shortly after their departure, a unit from Colonel Gorringe’s Flying Column who were tracking the Boers arrived, arrested Van Heerden and took him in the direction of Middelburg for questioning.

“They had scarcely progressed 100 metres when Boers on a nearby ridge fired down, lightly wounding two of the British soldiers. Van Heerden, however, was grievously wounded and had to be carried back into the farmhouse by two servants and his wife, who nursed him. The soldiers sent for an ambulance wagon to fetch their own wounded.

A veld execution

“The next day, some British soldiers arrived back on the farm, kicked open Van Heerden’s bedroom door and told him he had been found guilty (in absentia) of high treason and that he had exactly eight minutes before his execution.

“In Colonel Gorringe’s war despatches, he declares that there had been no time to take the matter to higher authorities and that he had wanted to make an example of Van Heerden.”

What followed was pure sorrow: Hendrik van Heerden was dragged from his bed, taken to a nearby stone kraal wall and shot, in full view of his family. The dying man’s last words to his wife were:

“Write on my gravestone: innocent blood, innocent blood!”

As part of his MA dissertation titled The Guerrilla War in the Cape Colony during the South African War of 1899-1902, Rodney Constantine singles out this incident:

“Van Heerden’s summary execution created great bitterness among the Midlands Boers and resulted in political tensions in Cape Town.”

The war of ghost patrols

Spare a kind thought for any researcher wanting to piece together the account of what really happened in the Eastern Cape Karoo during the Second Anglo-Boer (South African) War. The narrative is not as linear as, say, that of the Kimberley Siege, or the battles that took place at Colenso or Magersfontein. This is a story of ghost patrols, mounted guerrilla fighters who would raid Nieu-Bethesda one day, be spotted near Aberdeen the next, ride through the Plains of Camdeboo and then suddenly pop up in the Swaershoek Mountains the following morning. It’s a story of a group of strong-willed Boer commandants who criss-crossed the region, blowing up railway lines, plundering Brit-aligned farmsteads, ambushing mounted patrols and disappearing into the hilly landscape without a trace.

For the conventionally minded British military, it must have been like herding cats that fought back with long claws.

“Our military history has largely consisted in our conflicts with France, but Napoleon and all his veterans have never treated us so roughly as these hard-bitten farmers with their ancient theology and their inconveniently modern rifles.”

These are the words of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes but, more pertinently here, the author of The Great Boer War.

The fighting general

So, although this series of ferocious little fights might look to the untrained eye like never-ending ant-trails on a frantic rush just before the rains, the ultimate aim of the exercise was, it seems, to destabilise British military infrastructure and encourage the Cape colonials to join the Boer cause. There was also an element of reprisal against the Boers who had helped the British over the years of conflict.

This phase of the Anglo-Boer War probably began on December 15, 1900, when the legendary General Pieter Kritzinger pitched up in the area with more than 700 men at his side.

Five days later, martial law was declared in Graaff-Reinet, a town riven apart by rival factions. Loyalists feared that Kritzinger was on his way to seize what is today known as The Gem of the Karoo but breathed easier two weeks later when 600 Coldstream Guards came to town. Their numbers would be swelled to 2 000-strong within days.

The grave of General Pieter Kritzinger in Cradock. Image: Chris Marais

A farm in the Baviaans River district, where General Kritzinger and his men roamed. Image: Chris Marais

Pieter Kritzinger decided to briefly take the tiny Sneeuberg village of Nieu-Bethesda instead. If you’ve ever been to Nieu-Bethesda, you’d realise what perfect geographic sense it makes, for a large, roving band of raiders to strike from these mountains and then return to the hidden heights for rest and recuperation.

Kritzinger, however, was always on the move. By early January, his forces had clashed with a British patrol outside Murraysburg and by mid-month they had invaded Aberdeen to the south. Three days later, the Kritzinger commando captured Imperial Yeomanry troops near Willowmore, darted down to (and occupied) Uniondale and then scooted up to Klipplaat on February 6, taking a British troop of 25 men by surprise.

As the weeks passed the Imperials realised they were being whipped by small bands of very mobile Boers. Colonel G.F Gorringe then established his Flying Column to match them in the field. And the deadly game was on.

Other leading Boer fighters like Commandants Scheepers, Fouche, Naude, Lategan, Van Reenen, Botha, Bornman and Malan were also in the picture. If you were in a British-controlled town and you expressed support for the Boers, there was a good chance you would be shipped off to confinement in Port Alfred as an “undesirable”.

Snippets of the story

Weird things happened. History buff Andrew McNaughton told me about the time a little Boer farm girl visited Graaff-Reinet with her mother and, in passing the imposing statue on the town square (dedicated to locals who had fallen in World War 1), exclaimed:

“Look at the angel!”

At which her mother replied sternly:

“Don’t look. It’s an English angel.”

Officers of the occupying Coldstream Guards took over the Graaff-Reinet Club and, when peace was declared, had such a wild party over there that some grew reckless with their revolvers and shot the bar counter full of holes. Just outside Middelburg on the Richmond road, you’ll pass a stone memorial which bears the etching of a riempies stoel, depicting one of the chairs two men were tied to in October 1901, and executed by firing squad.

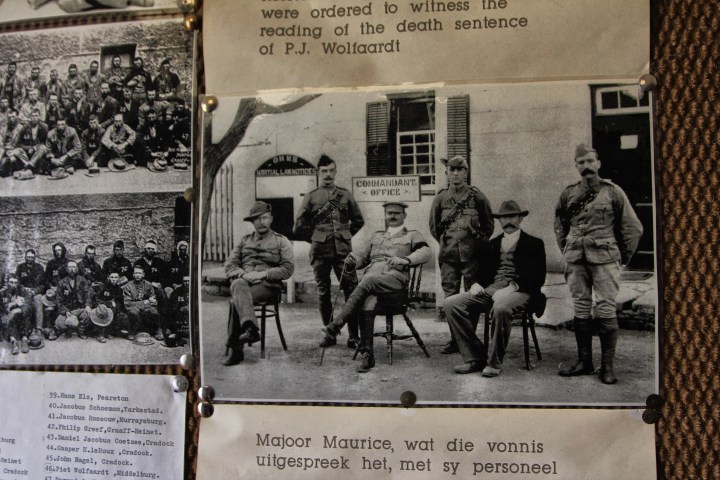

A scant month before, Commandant JC Lotter and Lieutenant PJ Wolfaardt and their unit of 117 men were surrounded by a large British force as they camped on a farmstead near Petersburg in the Camdeboo.

In the firefight that ensued they lost 14 men, killed 18 British troops but were eventually forced to surrender. Shortly after that, they captured another big fish, in the form of Cmdt Gideon Scheepers. Lotter, Wolfaardt and Scheepers were tried, sentenced to death as war criminals and executed.

The ‘English Angel’ on the Graaff-Reinet town square. Image: Chris Marais

Available horses and riding skills were paramount to both sides during this part of the Anglo-Boer War. Image: Chris Marais

Memorial to Messrs Lotter and Wolfaardt, executed by the British during the 2nd Anglo-Boer War. Image: Chris Marais

Treasure in Burgersdorp

Some time back, I had the chance to wander around Burgersdorp, a little town on the edge of the Karoo as you head north into the Stormberg ranges and beyond. Burgersdorp, for Anglo-Boer War travellers, offers rich pickings. The town square still sports an ornate drinking fountain dedicated to Queen Victoria and donated just before hostilities broke out. For some reason, the storks in the drinking fountain crown implore passers-by to “keep the pavement dry”.

The Taalmonument statue of a woman holding a tablet was damaged by the British, removed and replaced in 1907 with a replica. Only in 1939 was the original discovered – missing an arm and a head – found in a King William’s Town yard. They now stand together on the square.

A British blockhouse still standing on Hillston Farm outside Middelburg. Image: Chris Marais

A selection of photographic tintypes in the Burgersdorp Museum. Image: Chris Marais

On the hill overlooking Burgersdorp is a blockhouse called Brandwag (sentinel), but it was in the Burgersdorp Museum that I made my find, in the form of a pile of old hard-back photographs lying forgotten at the bottom of a dusty glass display case. The museum official kindly unlocked the case for me, retrieved the photographs and allowed me to copy them.

The images depicted Boers being shipped off to various penal colonies, nurses tending the wounded in field hospitals, a skirmish in a forgotten koppie somewhere, British soldiers disembarking onto South African soil, various parades, river crossings and gatherings of captured Boer fighters.

The wedding crashers

General Kritzinger moved his area of operations to the district around Cradock, across to Bedford and deep into the Baviaans River area, also known as the Pringle Valley.

Local lore has it that because he was fluent in English, Kritzinger often talked his way to safety when confronted by roadblocks or the occasional British patrol. But there was one wedding party in the Pringle Valley that had cause to admire him a little less than most.

British soldiers at rest in the Cradock town cemetery. Image: Chris Marais

A powder horn left behind at the Cradock Club by the occupying Sherwood Foresters. Image: Chris Marais

The Cradock Mother Church – British soldiers used the steeple as a watchtower. Image: Chris Marais

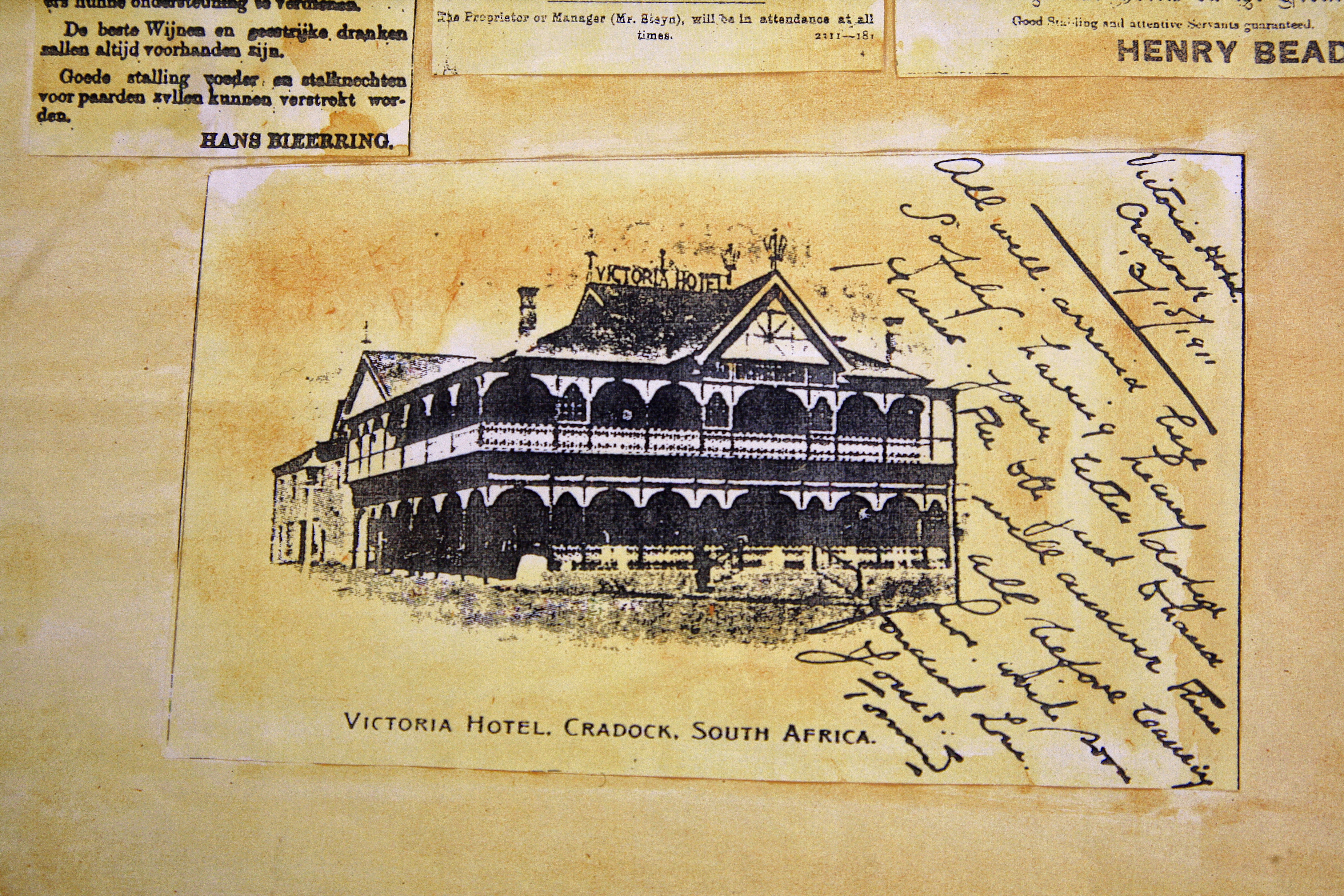

An old postcard from the Victoria Hotel in Cradock. Image: Chris Marais

In his book titled The Baviaans River – Stories, People and Places, Clive Cawood tells of an event that happened on Cheviot Fells Farm.

The Boers under Kritzinger arrived there and demanded food. Farmers were not allowed to keep more than two weeks’ supplies on the farm, so the only available food was a wedding cake belonging to Edward Rennie and Katherine de Beer, who were to tie the knot that weekend.

“This was consumed with enthusiasm by the Boers,” writes Cawood.

During this phase of the war, Cradock’s Victoria Hotel basement was used as a lock-up for Boer prisoners and the Moederkerk became a British lookout post. War correspondent Edgar Wallace reports in New Zealand’s Evening Post in October 1901:

“And so the roof of Cradock’s pretty church was garrisoned, and a man in khaki wagged a flag from its steeple, and sober businessmen shut up their shops and ran a ‘pull-through’ through their rifles, and the man who at 9 o’clock was serving out butter, was at 10 o’clock serving out ammunition…”

The Cradock market square between the Moederkerk and the Victoria Hotel was where the occupying British executed those Boers they deemed to be “Cape Rebels”. The hangings were performed publicly and all Afrikaner adult males were ordered to attend.

Johannes Petrus Coetzee, a local man said by the British to be 21 years old at the time, was convicted of high treason under arms and murder, and hanged here. Recent published works have his age at a mere 16, a fact which was apparently brought to the attention of the British Parliament by activist Emily Hobhouse but kept away from the public at large. Was this a war crime? It would not have been the first, or the last. DM/ML

This is an extract from Karoo Roads II – More Tales from the Heartland, by Chris Marais and Julienne du Toit.

For an insider’s view on life in the Dry Country, get the three-book special of Karoo Roads I, Karoo Roads II and Karoo Roads III (illustrated in black in white) for only R800, including courier costs in South Africa. For more details, contact Julie at [email protected]

interesting read as always. Thank you.

Fascinating article Chris!

Amazing that more of this kind of stuff is not really heard of today!