SPOTLIGHT

‘That iron suitcase saved my life’: 90-year-old nurse and midwife reflects on a lifetime of service

Friday 5 May is International Day of the Midwife. Ufrieda Ho chatted to the remarkable nurse and midwife, Boitumelo Motsei, about her 37 years working in healthcare and why she still has hope for the nursing profession.

When Boitumelo Motsei became a nurse, she didn’t expect that she would also have to learn to ride a bicycle or drive a donkey cart.

“The bicycle was better – it was faster,” says the 90-year-old with a laugh.

She is seated at the dinner table of her home in Kgomo Kgomo village in Makapanstad in the North West. It’s the house she moved into in 1957 after agreeing to become the wife of Rantebo Motsei and qualifying as a nurse the year before.

The nonagenarian says that in the 1950s, South Africa – in the stranglehold of apartheid – offered few professional career choices for a black woman. In fact, virtually only two – become a teacher or a nurse. Both would be careers that came with the reality of working in remote rural postings, often without the basics of running water, electricity or transport – apart from donkey carts and bicycles.

But once Motsei settled on her decision to serve and help heal the sick, she didn’t look back. By the time she retired in 1989, she had clocked up 37 years of service in public health.

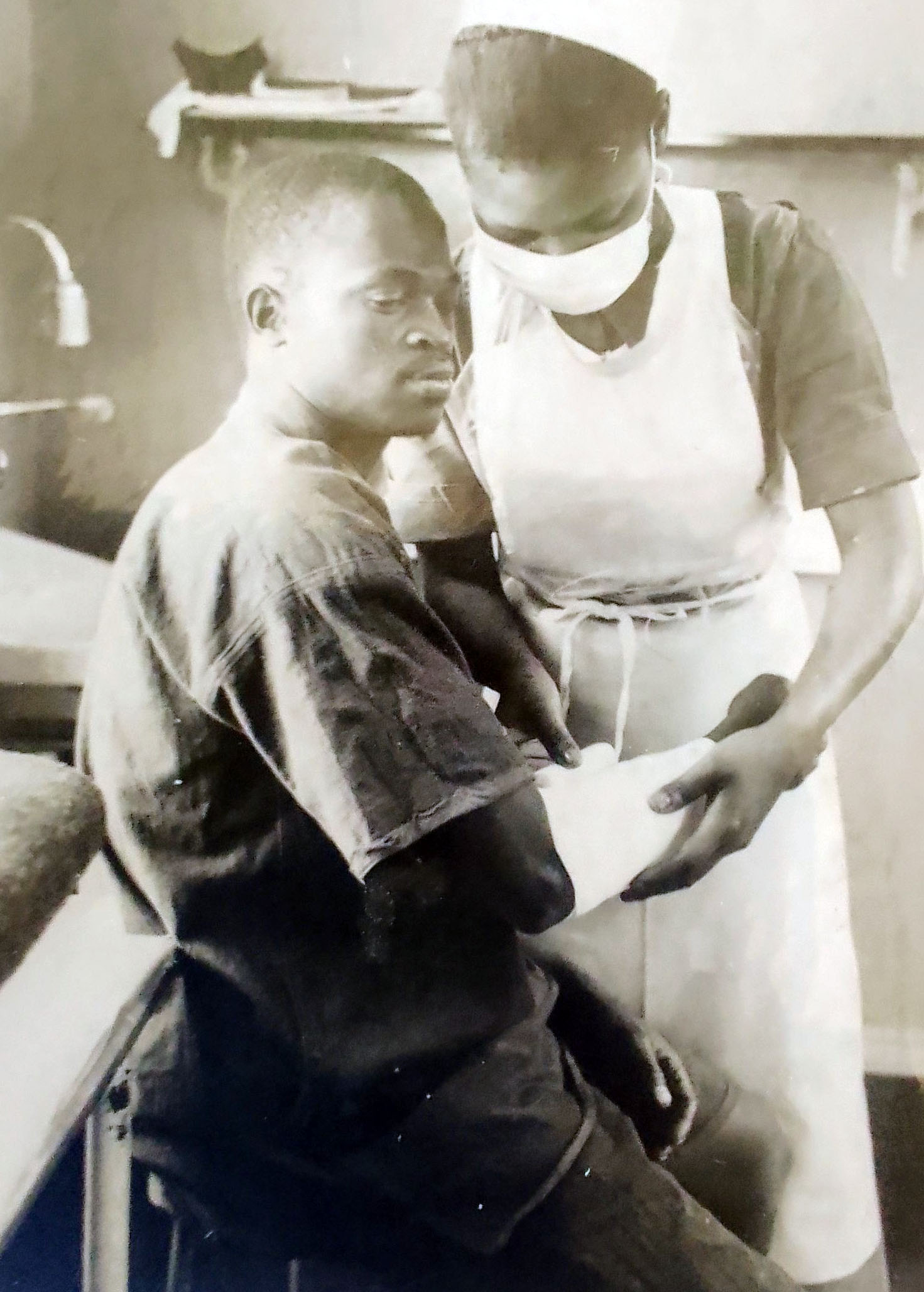

In 1961 Boitumelo Motsei helped start the Mathibestad clinic. Black nurses and midwives like Motsei were often the backbone of rural healthcare in apartheid South Africa. PHOTO: Supplied

Nursing would become a lens through which she witnessed the limits of the physical body, but also its miracles. It would be her front-row seat experiencing human beings in their weakest moments on a sickbed and also in mortal triumph taking one more unpromised breath. Hers would be a career intertwined with the expression of the rawest of human emotions, behaviours and actions.

Her first posting, after completing her nursing college education in Elim, Limpopo, was in the old Louis Trichardt area, which today is Makhado.

“I realised quickly that one of the first things I had to do was to learn to speak Shangaan. Every morning the clinic started the day with a prayer in Shangaan, so I started to pick up the language and within eight months I could speak it,” she says.

Honing her communication skills and practising tolerance would mark how she chose to approach whoever came to be her patient. Her professionalism and attitude raised the profile of nurses and allowed communities to trust and respect “this small, young woman” who arrived as a stranger.

Working with traditional leaders

“When you work in these communities, you have to work with the traditional leader and his council – these older men sometimes did not have any formal education and you would be coming there from the outside. So you had to give them respect and earn their trust,” she says.

Her first specialisation was in midwifery. Being responsible for helping to bring new life into the world demanded trust of the most intimate kind. Motsei retells how runners from far-flung villages would knock on her door at all hours with the message of a woman in labour and she had to head out.

“If it was at night I would take a torch and tie it around the front of the bicycle so I could see where I was going. I also had to take my suitcase that I used to carry the things I needed to check the baby’s and the mother’s health.

“When people in the village saw the torchlight, they would shout ‘the nurse is coming, the nurse is coming’. Even the young men who were playing dice would stop and the elders would send one of them with me to find the home where the woman was giving birth, and the young man would be told to wait till the baby was born and then to show me the way back home,” she says.

Midwifery, she says, meant she also had to let into the room the older women in the community, as well as the village inyanga who would first throw the bones before Motsei was allowed to attend to her patient. Allowing space for customs and hierarchies, though, was how she ensured peaceful cooperation that enabled her to do her work.

“When the baby cried for the first time, it would be jubilation outside and that was wonderful.

“After the birth, the old women and the inyanga would inspect the placenta with me, and then the placenta would be taken away to be buried – except for the Shangaans… They would bury it in the spot where the baby was born. It was the custom so that the woman would never run barren,” she says.

Boitumelo Motsei clocked up 37 years of service in public health as a nurse and midwife. PHOTO: Supplied

Midwifery in villages meant sometimes Motsei was literally on her knees, on the ground assisting a woman in labour. She says she often helped to build a bed of dried cow dung covered with old sacks as the birthing bed.

‘That iron suitcase’

As for her suitcase, she eventually had someone reinforce it with zinc sheets.

“That iron suitcase saved my life – I had to walk long distances as a village nurse and that suitcase meant I could take a rest under a tree and sit on it as a chair,” Motsei remembers.

She says since it was a government-issued suitcase, she had to leave it behind when she moved on to her next posting.

Midwifery would dominate her career for nearly 15 years and she would deliver dozens of babies, people who are now in their 50s and 60s. She would also, in 1961, start the Mathibestad clinic. They built their own shelves for a makeshift dispensary and held health and cultural days, she says, paging through old photo albums filled with memories and milestones.

“It was very peaceful then. I never had a single complication, and they were all healthy babies,” she says.

Later in her career, she changed gears to do another specialisation in public health. Her work included driving a mobile clinic to remote communities. She laughs that it was an upgrade from the bicycle and the donkey carts. Home visits were focused on hygiene for people who had no running water or proper sanitation. But it was also about seeing her patients in their day-to-day realities and challenges and recognising that health and wellbeing are always directly linked to people’s personal circumstances.

Motsei would also become a school nurse serving several schools in her district.

“The children were easy to work with but some parents could be tight and stiff and some of them would come to me and ask why their children opened up more to me – about menstruation [and] even teenage pregnancy. I would say they should speak softly to their children and let them come with their own views on things,” she says.

Boitumelo Motsei’s first posting as nurse and midwife was in the rural area of Makhado (formerly Louis Trichardt) in Limpopo. PHOTO: Supplied

Collecting stories

Motsei had six children of her own. She continued to work throughout, juggling her career and motherhood and occasionally indulging in her hobby of collecting stories from the community while journaling her own experiences.

Her eldest daughter, Mmatshilo Motsei, is an author, academic and activist. She followed in her mother’s footsteps, qualifying as a nurse and a midwife in the 1980s, but did not practice, noting that career choices for black women had changed very little, even one generation on.

For Mmatshilo, there are honours due to the black nurses and midwives like her mother who became the backbone of rural healthcare, but who she says are still sidelined or simply erased from the story of nursing in the country.

Mmatshilo says the legacy of apartheid was implicit in putting limitations and barriers on women like her mother.

“Black nurses were expected to work in hospitals and clinics that were overcrowded and under-resourced. If you were a white nurse working there, you would have been the matron.”

Mmatshilo has honoured her mom – the woman she calls “an archivist of note” – by publishing her biography last year. It’s called, “Bothshe Jwa Puo” in Setswana, translated as “Sweetness of the language”.

Motsei says she has at least seven files of material she’s collected since the 1980s and her retirement years could well be about finding a way to share the wisdom and reflections she gathered and documented.

The files contain stories through which she says black people can hear from elders and reclaim their dignity, identity and self-worth. They are also reflections for people to learn to respect each other across racial and cultural divides, and, ultimately, for her beloved profession of nursing to find its heart again.

90-year-old former nurse and midwife, Boitumelo Motsei spent almost four decades providing healthcare in rural North West and Limpopo. May 5th is International Day of the Midwife.Photo:Denver de Wee/Spotlight

‘Things are different now’

“Things are different now in nursing,” she says. “I know why there came a time when people started to say ‘nursing has gone to the dogs, and the dogs have come to nursing’ and I hear and see this.”

Motsei says, “Nursing must go back to the time of Florence Nightingale [the British nurse dubbed the Lady of the Lamp and credited for reforming and modernising nursing in the mid-1800s and going beyond the call of duty to put patients’ needs first]; when nurses used to care for their patients, even by lantern light.

“But I’m not talking about paraffin for the lanterns,” she says, “I’m talking about nurses filling those lanterns with some pity and also some love for their patients and their work – this is how we will make nursing strong again.” MC/DM

This article was published by Spotlight – health journalism in the public interest.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

I love those photos, such dignity and pose. Thank you for sharing a story of a seemingly unimportant person, but on closer inspection brought a work ethos, a community ethos and caring ethos that shouts out about being a person of value and integrity. These women are my role models, they made it happen irrespective of the circumstances. Could I walk in those shoes with such grace and power? I am humbled and grateful that these stores are being told. Real people making a real difference. Thank you for sharing.