REFLECTIONS

Lessons from women writers – my poetic journey with books from the Little Karoo to Amsterdam

‘Remember that the book which bores you when you are 20 or 30 will open doors for you when you are 40 or 50, and vice versa. Don’t read a book out of its right time for you’ (Doris Lessing).

As a first-year undergraduate I had a panic attack when the canon of world literature fired a warning shot across my bow. The academic path stretching out ahead of me seemed strewn with insurmountable obstacles. How would I ever manage to read all those hefty literary tomes – The Divine Comedy, The Canterbury Tales, Paradise Lost, Don Quixote, David Copperfield, Middlemarch, War and Peace, Moby Dick, Buddenbrooks and Ulysses – and find time to smoke dope, get laid, listen to music and have a life?

When I encountered Doris Lessing and came across the quotation I’ve used as an epigraph, I felt less apologetic about the lacunae in my reading. And if Lessing said it was okay to buy a book on an impulse and leave it unread on your bookshelf for up to 20 years, who was I to disagree?

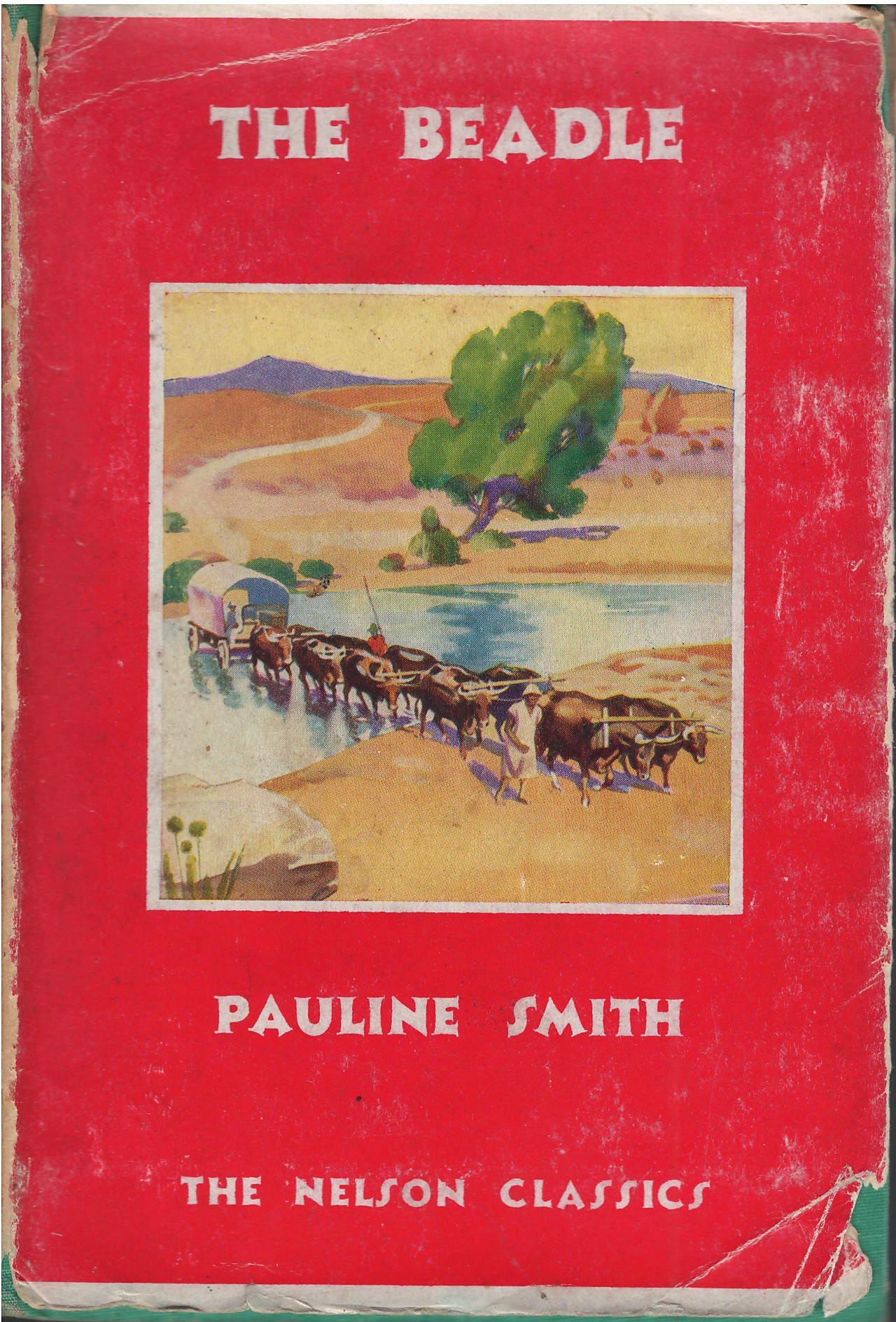

But when I read Pauline Smith’s The Little Karoo for the first time, I did wonder why I’d waited so long.

She really was good and I wanted to read more. So I took the five-minute stroll from my apartment in the red-light district to Antiquariaat Schuhmacher, a second-hand bookdealer on the Geldersekade, and asked if they had any South African books. They did and I made two purchases.

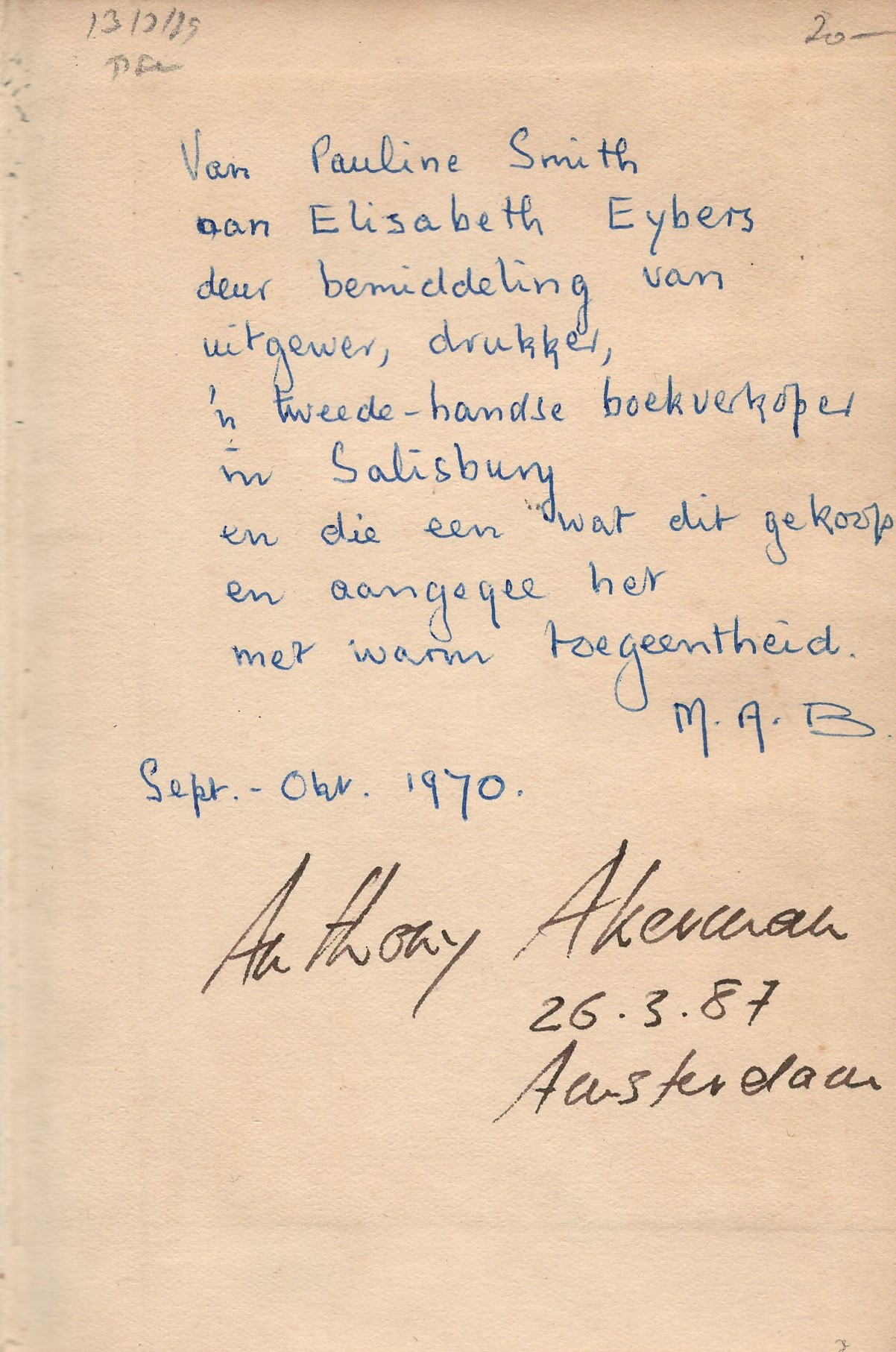

From Pauline Smith to Elisabeth Eybers through the good offices of a publisher, printer, a second-hand book dealer in Salisbury and the one who bought it and passed it on with warm affection.

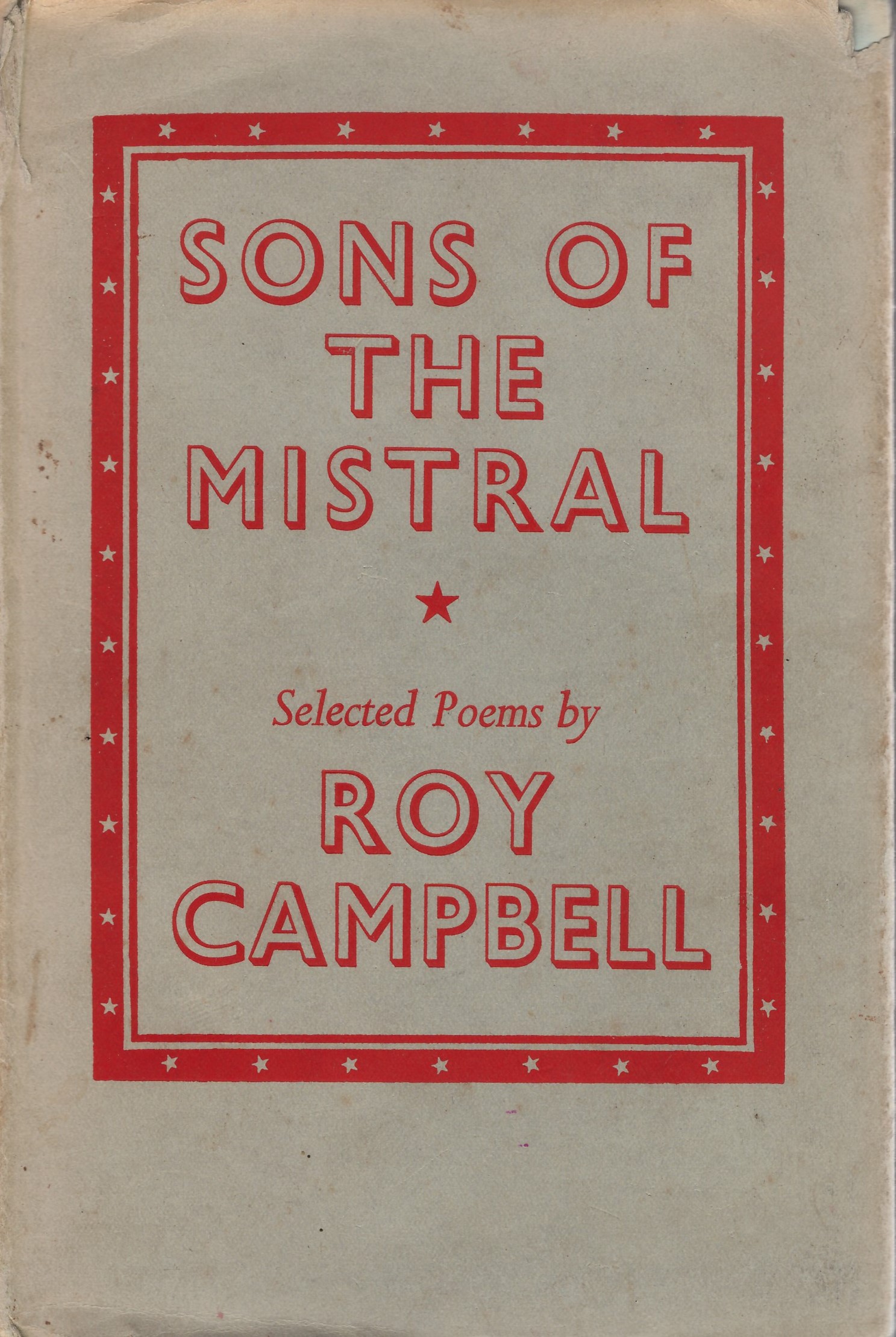

One was Pauline Smith’s novel The Beadle and the other was a second impression of Roy Campbell’s Sons of the Mistral (1941), which I picked up for next to nothing. There clearly wasn’t much demand for Campbell in Amsterdam.

Campbell rated Pauline Smith. Although I didn’t know this when I was standing there handing over ƒ 21,50 to the book dealer, in December 1926 a youthful Campbell had the following to say about her in a letter to CJ Sibbett, an advertising man from Cape Town, who was to become both a friend and benefactor.

“She is the only woman-novelist that is any good out here. The Little Karroo has some very fine work in it. The Beadle, though not so good, shows that she is capable of developing. Most of the women-writers I know would have gone on repeating themselves once they had discovered so excellent a mannerism as that employed in The Pain. To repeat oneself is the secret of popular success – it’s called ‘fulfilling one’s promise’ – and should be shunned like Hellfire by an artist. Most women-artists are unable to resist ‘fulfilling their promise’. But here is one who isn’t. Good luck to her.”

If a slightly misogynist tone seeps through in the way he speaks about “women-writers” that can be attributed to him crossing swords with the popular novelist Sarah Gertrude Millin, who was soon to become the butt of his most famous and stinging epigram “On Some South African Novelists”.

I went back to my flat and found a suitable place for The Beadle alongside Ralph Iron’s The Story of an African Farm (1892 edition) in my meagre – but growing – collection of South African classics. I had every intention of reading it but was soon distracted after having taken the decision to visit South Africa for the first time in 14 years. I thought it’d lend me an air of nonchalant confidence if I booked my flight and only then applied for a visa – almost as an afterthought.

My dealings with the South African embassy had been stilted since 1978 when they started renewing my passport for a year at a time. As soon as I could, I renounced my citizenship and became Dutch – something they seemed to have taken rather personally. They also knew my play Somewhere on the Border had recently been performed in South Africa, where it had stirred up controversy and, in the words of the Directorate of Publications, had placed the South African Armed Forces “in an extremely bad light”. I was subjected to an uncomfortable interview that mercifully stopped short of an anal probe, after which I was drawn into a cat-and-mouse game with embassy staffers which continued until the day before I was scheduled to fly home. That’s when they told me my visa had been declined.

With all that going on, I must have forgotten about The Beadle. Five years later it was packed into a box, transported to Johannesburg and took up a new place on yet another bookcase between The Big Sleep and Portnoy’s Complaint.

If Doris Lessing thought reading a book 20 years after you’d bought it was perfectly acceptable, when I took it down and opened it the other day, I realised it had been waiting forlornly on my various bookshelves for 35 years. Then I saw the inscription above my name and the date of purchase. I obviously hadn’t paid close attention at the time. What did it mean? Pauline Smith died in 1959, so she couldn’t literally have given instructions in 1970 to M.A.B. – whoever that was – to give the book to Elisabeth Eybers.

But who was the mysterious M.A.B. who, on a visit to what was then Rhodesia, had paid 4/6 to a second-hand book dealer in Salisbury – either The Treasure Trove or The Book Exchange, according to my informants – and “passed it on with warm affection”? If anyone knew the answer to that question, it would be Ena Jansen.

Ena is, among many things, an eminent Eybers scholar, who became her friend and, in 1996, wrote the outstanding Afstand en verbintenis (Distance and Connection) about Eybers’s life and work in Amsterdam. She told me M.A.B. was Marié Antoinette Botha, whose married name was Bax. Although she was three years older than Eybers, they’d both studied at Wits in the 1930s, remained close friends and, after Eybers settled in Amsterdam in 1961, Marié often stayed with her in the Van Breestraat.

So how did the novel end up in Schuhmacher 17 years later? Ena said Eybers was forever giving books away. Perhaps she downsized when she moved from the Van Breestraat to the Stadionkade in 1979 and ever since then it had been waiting patiently for me to walk through the door.

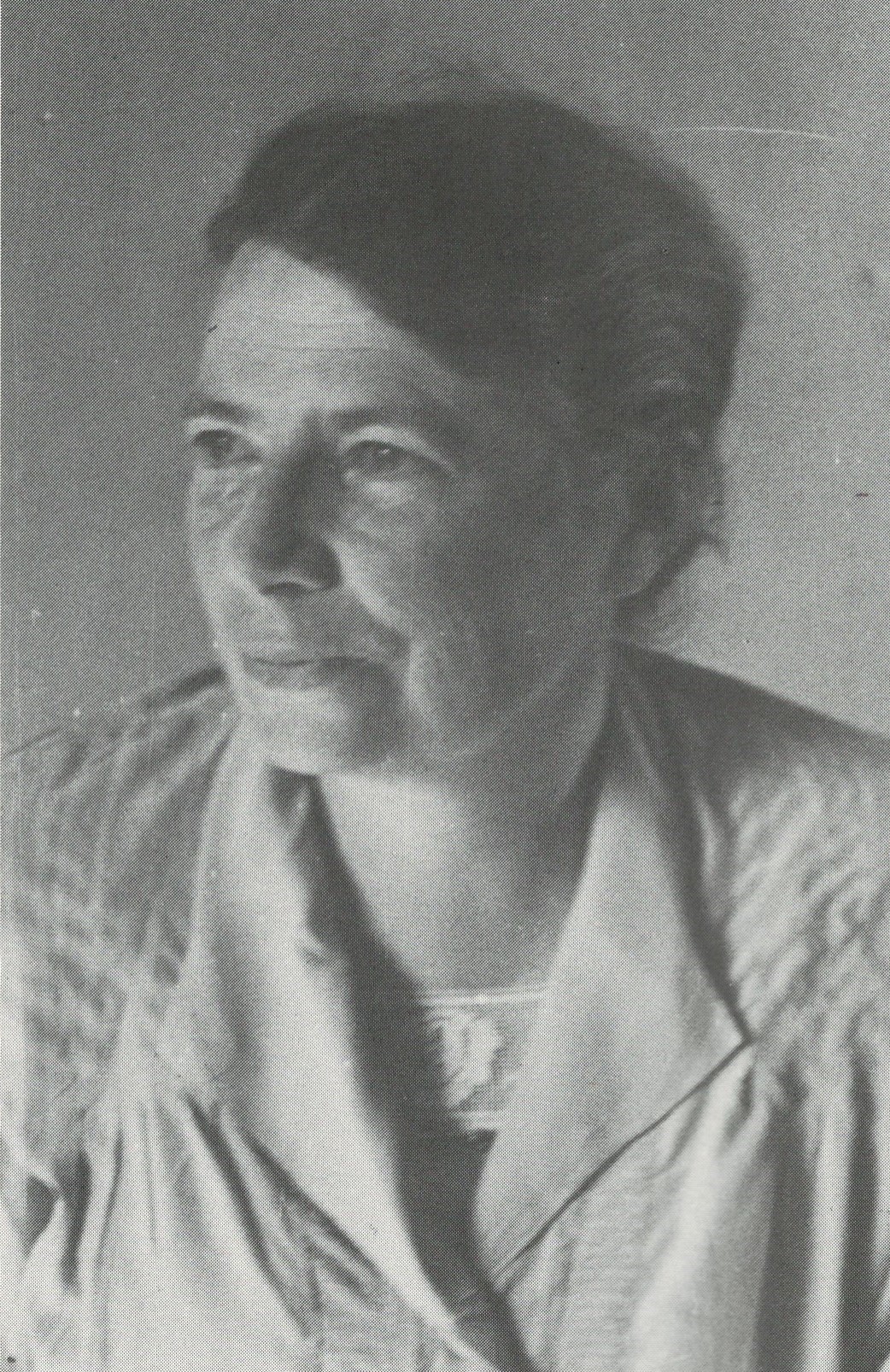

Pauline Smith.

Although we’d lived in the same city, I’d never met Elisabeth Eybers. She’d already turned 60 by the time I arrived in Amsterdam in 1975 and was never part of the South African exile diaspora. She was reclusive, didn’t give radio and television interviews and seldom expressed herself publicly on political issues. She was respected in Dutch literary circles and, as Ena has pointed out, her poetry was probably the only Afrikaans poetry readily accessible to Dutch readers in the original.

In 1989, she agreed to be interviewed for the Dutch literary magazine Tirade. The interview – conducted by Tomas Lieske and Willem Jan Otten – was scheduled for early 1990 to coincide with her 75th birthday. Willem Jan was a friend and I remember having supper with him shortly after he’d interviewed her. He was still trying to get his head around the fact that he’d actually interviewed “the very first poetess in the entire language”. It was an excellent interview and in September 1994 my English translation was published in New Contrast. I was passing through Amsterdam in December that year and hoped I’d be able to drop it off and finally meet her.

I don’t recall whether Ena gave me Eybers’s phone number or whether she was listed in the telephone directory, but I made a cold call, introduced myself – probably speaking Dutch – and asked whether I could deliver copies of New Contrast in person. She told me she was recuperating from knee-replacement surgery, still needed a walking frame to get around and apologised for not feeling up to being hospitable. We spoke for about 20 minutes, switching between Dutch, English and Afrikaans. She gave me her address and I promised to post her the magazines.

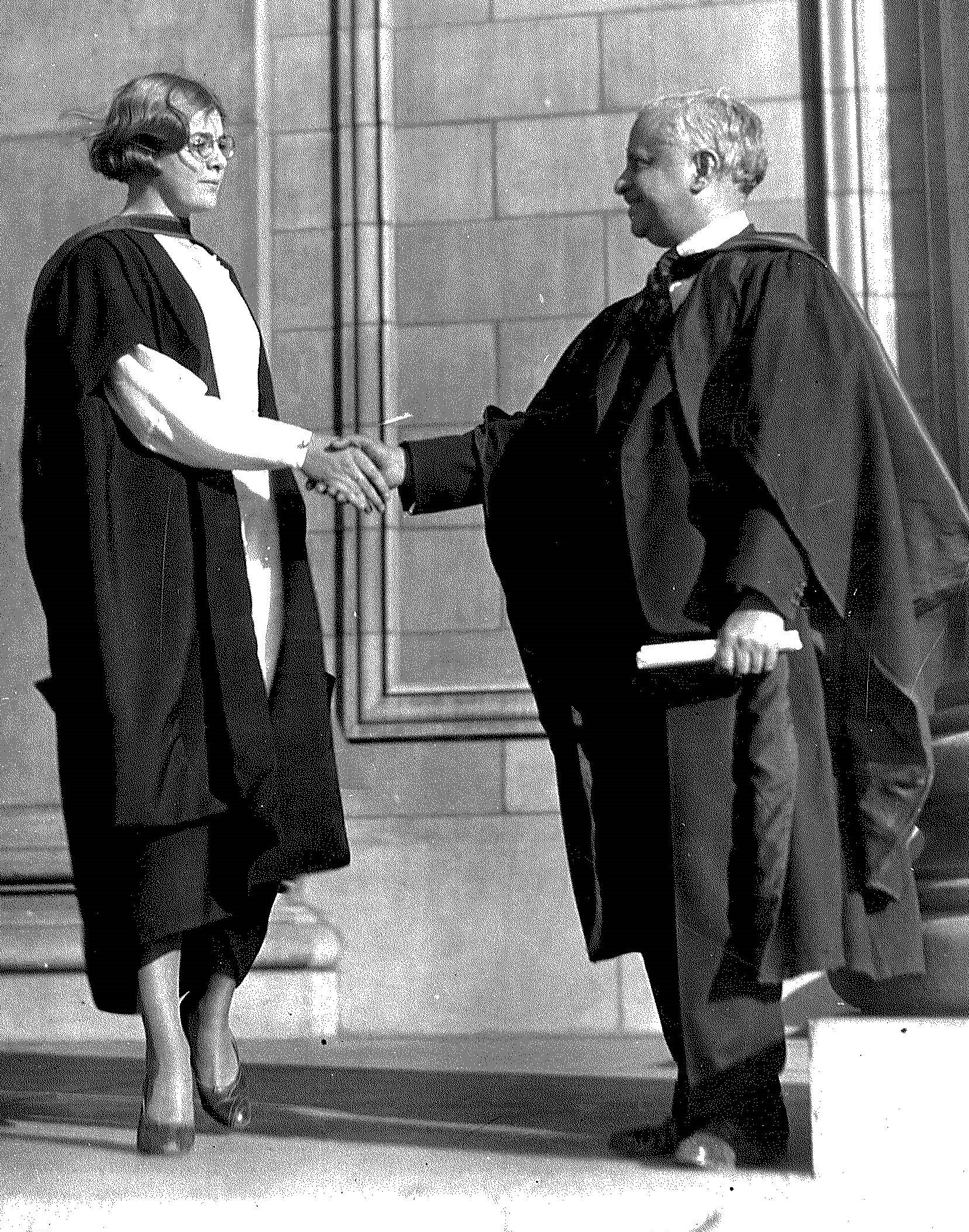

Marie Antoinette Botha being congratulated at her graduation by Professor LF Maingard. (Photo: © University of the Witwatersrand photo archive)

I told her about my play Dark Outsider and she said she was “deeply interested” in Roy Campbell. It had already been broadcast on what was then Radio South Africa and I offered to send her an audiocassette. Before we ended our call, she mentioned she was turning 80 in February. She added that she now felt too old to travel and would in all likelihood never visit South Africa again. That made me profoundly sad. By then she’d lived in Amsterdam for 33 years, yet she spoke both English and Dutch with an unmistakable Afrikaans accent.

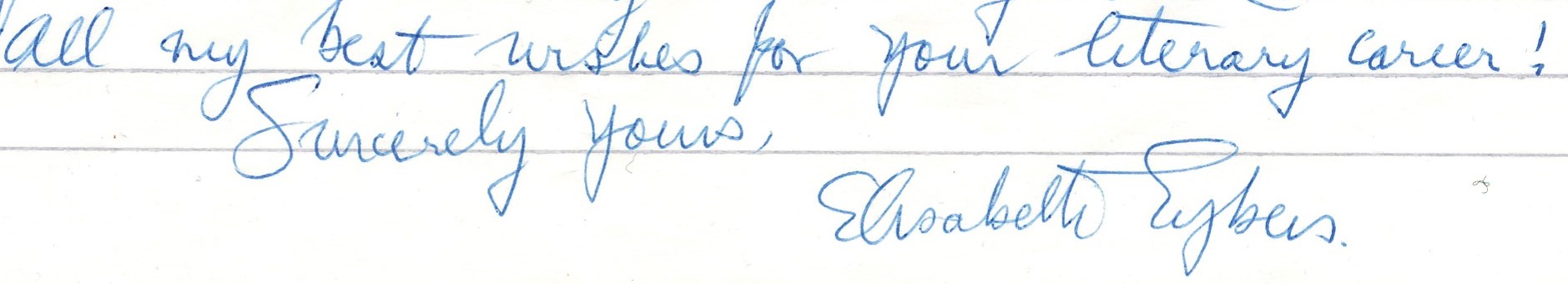

After arriving home on a flight from hell – well, let me not exaggerate, on a Balkan Bulgarian Airlines flight crewed by unsmiling former KGB agents – I received a letter from her thanking me for the copies of New Contrast and the audiocassette. She added apologetically that she was “technically backward”, didn’t have a cassette player but that her daughter Jeanne had promised to lend her one. She ended off with the words, “All my best wishes for your literary career!” I never did hear whether she managed to play the cassette and she never again visited South Africa. In 2007, she was laid to rest in Amsterdam’s Zorgvlied Cemetery.

Elisabeth Eybers. (Photo: © Ena Jansen)

A benediction from Elisabeth Eybers.

I don’t think The Beadle is less good than anything else Pauline Smith wrote. She powerfully conjures up the prelapsarian Little Karoo of her childhood, populates this world with vividly drawn characters and, from early on, introduces an unsettling sense of foreboding. She’s a consummate storyteller and brings her novel to a conclusion that’s satisfying, moving and unsentimental.

While I was turning the pages of this 1938 Nelson Classic, I imagined Elisabeth Eybers sitting in an armchair with this novel in her lap, staring through the window at a wintry Amsterdam sky and being overcome by a sense of longing for Smith’s Aangenaam Valley. Then she picked up the book given to her by her dear friend Marié and resumed turning the pages – the same pages I was turning 52 years later. In that moment I experienced a visceral connection with the very first poetess in the Afrikaans language – and I felt especially privileged to have received from her the blessing with which she ended her letter. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Try some present day Little Karoo books. Start with Sally Little.

Thank you for this Anthony. Well written and well appreciated!

The Beadle is THE Great South African novel. I could make no greater claim. In the right hands it would make a wonderful film. Pauline Smith’s Stories of the Little Karoo are among our most treasured literary heritage. Anthony, try Percival Gibbon’s Margaret Harding for another neglected but very fine writer who set his stories in the Karoo.