HISTORY REVISITED

Remembering history — Klaas de Jonge and the great (non) escape

Sidley, a veteran journalist in South Africa, remembers the escape of Dutch national Klaas de Jonge from prison in 1985 and his holing up for over two years in the Dutch embassy in Pretoria, before he was allowed to leave SA as part of a dramatic prisoner swap. In 2019, De Jonge was given the Presidential Order of the Companions of OR Tambo (silver). He had turned it down earlier when it was to have been presented by President Zuma. Sadly De Jonge, now 85, is suffering from terminal cancer.

In 1985, South Africa’s then-foreign minister, Pik Botha, faced a gigantic headache. It was caused by Klaas de Jonge, a Dutch national and anti-apartheid activist, who had been arrested by the South African security police for smuggling arms into South Africa.

De Jonge would have been a great prize for the apartheid state. He was working in Umkhonto weSizwe, having been recruited by Joe Slovo for special ops and had diligently been ferrying arms into South Africa in a Peugeot 504 with a special space built into it to hide the arms.

But on 9 July that year, whilst under intense and brutal interrogation, De Jonge took the police on an excursion showing them among other things, where he had supposedly hidden arms caches. Or so they believed.

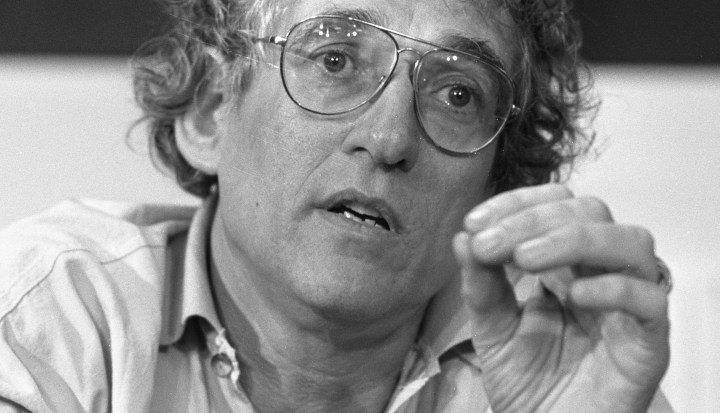

Chris Hani and Klaas de Jonge at a rally in Transkei, November 1990. (Photo: MyANC / Facebook)

The security police were led to the centre of Pretoria near Church Square where the Dutch embassy was situated in the Nedbank Building. Claiming there were arms stored in the building De Jonge — clad in leg irons — ran inside hoping to seek refuge on Dutch ground in the embassy.

But the police, in contravention of international convention, entered the Embassy premises, despite it being notionally on the ground of the Netherlands, grabbed De Jonge and dragged him back out, returning him to his jail cell.

Presumably happy with their handiwork, the police were unlikely to have understood the diplomatic storm their action would unleash.

Botha’s headache began when the Dutch government informed their South African counterparts that they had committed a grave error of judgment and asked for his immediate return to the embassy.

Initially, this was not granted. But eventually, succumbing to significant pressure to respect international law, on July 18 they handed De Jonge back. So began De Jonge’s 26-month stay in the embassy.

26 months holed up in an embassy

De Jonge had been detained on his way to Harare, where he lived, after spending the evening burying an arms cache with his former wife, Hélène Passtoors. She too was picked up by the police a few days later.

The security police had recorded the entire thing. Aside from evidence at a trial, this was useful to prove to foreign governments that the Dutch national they had detained was indeed a “terrorist” — in their terms — who had been smuggling arms into South Africa.

The story quickly became a major story in the Dutch press.

At the time I was the local stringer for the Dutch news agency, ANP. Although missing De Jonge’s arrest, I did the next best thing and filed a story confirming his detention, stating the allegations and saying that he had no access to lawyers, consular officials or anybody else.

In Harare, his son became worried when he failed to keep an arrangement. He sought the help of a friend who contacted Kathy Satchwell, then a young attorney — now a retired judge — who took on the case.

Pik Botha’s headache meanwhile was not subsiding. The Dutch government was insistent that De Jonge be returned to the embassy, while De Jonge was being interrogated with a view to charging him under the then notorious Terrorism Act. The South African government wanted to detain him and charge him, together with Passtoors, for the same crimes.

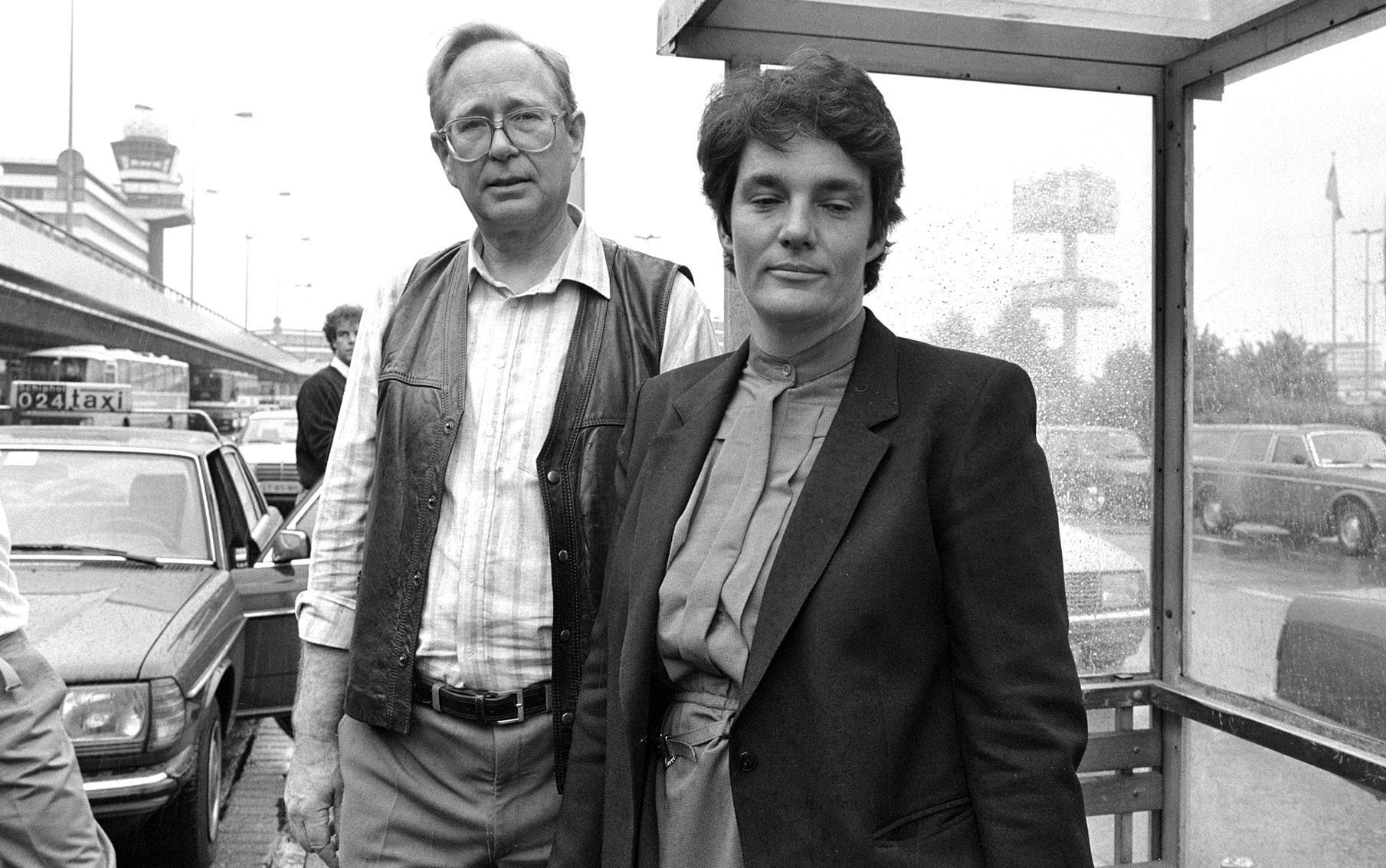

Klaas de Jonge after his stint in South Africa, upon his arrival at Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam on 8 September 1987. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Although there was diplomatic movement in the background that was done behind closed doors. But three weeks later they unexpectedly handed De Jonge back to the Dutch Embassy, which had not been expecting him and which had no facilities for its unintended guest.

In the meanwhile, this had turned into a major story both in South Africa and in the Netherlands.

The South African press was largely unconvinced that De Jonge and his case deserved serious consideration let alone support for his cause. The ANC was still banned and anybody with a modicum of support for it was considered an enemy. De Jonge fell squarely into that category.

My agency in the Netherlands serviced most Dutch newspapers. The South African Government had seen to it that few Dutch journalists were given permits to work here and so the Dutch press working with South African stringers like me, ran stories with a slightly differing tenor.

News surrounding the arrest was hard to come by — without a good leak from somewhere connected. De Jonge provided some of that news himself. He used to hang out of his window on the second floor of the building greeting the crowds that gathered regularly.

He also took to certain theatrics to annoy his captors who stood guard day and night waiting for him to try and escape so that he could be rearrested. For example, he blasted the song “Free Nelson Mandela” out of his window into the street below, delighting sympathetic members of the public but drawing the ire of supporters of the regime.

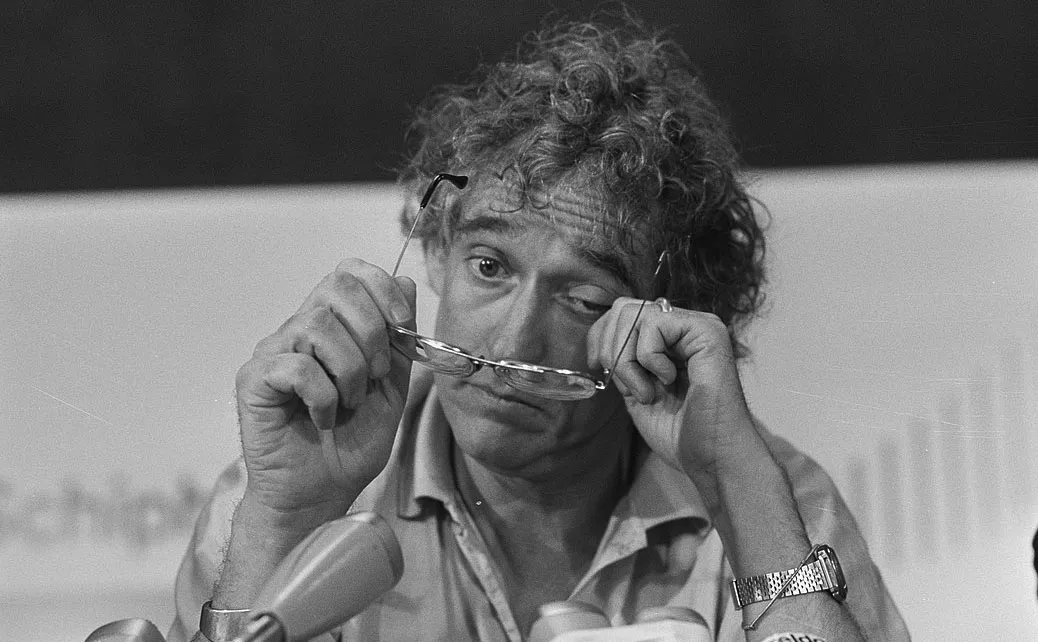

Sadhan Naidoo, son of Phyllis Naidoo with Klaas de Jonge on the left. Sadhan was assassinated with another MK Cadre Moss Mthunzi by Vlakplaas operatives. This image was taken on a farm in Lusaka in 1989. (Photo: Twitter)

Conversations with a fugitive

Then my luck changed. One evening I got a phone call from the embassy. One of the more sympathetic of De Jonge’s hosts or Military policemen from the Netherlands guarding him had rigged up a direct line to me.

This began a long conversation with De Jonge peppered with “scoops”. We dealt with much on that line, which was no doubt being listened to, including whether or not his arms caches had been used to cause civilian deaths.

Several nights a week we spoke. I became a continuing source of stories about De Jonge, some of the background issues and his life in the embassy.

One of the major issues which had arisen was the fact that the Dutch government was moving its embassy to different premises in Pretoria. What would become of De Jonge? Satchwell stepped in to try to negotiate a resolution.

The Dutch, while often irritated by his presence, were still disinclined to hand him back to the South Africans. The South Africans did not want to recognise the old embassy as territory of the Netherlands any longer and, said Satchwell, they would not give safe passage to De Jonge were he to leave the old embassy building.

Kathy Satchwell (right), attorney for Klaas de Jonge, arrives at Schiphol, the Netherlands. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

A third dynamic which crept in was the lease and the landlords — Nedbank. The embassy was due to move on August 23, 1985 and the lease on the Nedbank premises was due to expire on September 30. Nedbank did not want to extend the lease.

The legal issue was whether or not the empty premises could still be regarded as Netherlands territory. The issue was resolved. The empty embassy continued to house De Jonge and was to all intents and purposes regarded as Netherlands territory.

Klaas was left to himself, the Dutch guards, and occasional visitors arranged for him by Satchwell who found four friends of hers willing to visit De Jonge regularly. He was also allowed “conjugal visits” from his Harare girlfriend, Beverly Matheson, apparently granted to pacify De Jonge who at times became restive. Matheson was able to stay overnight — provided, according to Satchwell, there was no sex! This was not an embassy rule but her own, which with hindsight seemed ridiculous and was no doubt broken.

On her way to and from Harare, Matheson stayed with me. Pretending to be a clerk, I was smuggled in to visit and interview him by Satchwell. However, when the guards came to check on the room as the evening shift was to begin, I had to hide under his desk and they thankfully missed me. When he was eventually to be released it was celebrated with a party at which I was also present.

A further surprise came when one day De Jonge asked me to help him escape. The plan was elaborate and would have required a motorbike driven by me being brought to the embassy. I declined. Satchwell was shown his escape equipment. He was not one to be held captive quietly.

Prisoner swap

There had to be a resolution though. Satchwell found herself travelling several times to the Netherlands to negotiate a deal which was eventually to take the form of an elaborate prisoner swap.

Satchwell, on her own initiative, flew to Paris to visit Madame Mitterrand (wife of then French president Francois Mitterrand) who was known for her support for human rights causes. Satchwell told her of a French School teacher jailed in Ciskei — Pierre-Andre Albertini — for his dealings with the ANC and suggested that in a prisoner swap, she might want to include Albertini. This brought France into the elaborately evolving negotiations.

On their side, the South Africans wanted a senior South African Defence Force (SADF) officer, Wynand du Toit, returned — he was being held in Angola. To secure his release they were prepared to give up 133 Angolan soldiers and a few Cuban prisoners in return.

Eventually, a large array of parties to the negotiations included the Netherlands, South Africa (which inserted the unrecognised Ciskei bantustan into the picture) France, Angola and Unita. At the end of several rounds of talks, on 8 September 1987, the swap took place on the tarmac at Maputo airport.

A total of 133 Angolan prisoners and some Cubans were exchanged for Wynand du Toit; Klaas de Jonge and Albertini were returned to their countries. This too was not without drama: De Jonge’s belongings were laced with a herbicide poison which blinded him in one eye, thought to have been placed there by South African security police.

Klaas de Jonge returns to Schiphol, the Netherlands on 8 September 1987, after being detained in the Dutch embassy in Pretoria for almost two years. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Recognition by democratic SA

The ending of this story will be tinged with sadness for many, though no doubt celebrated by a few die-hard supporters of the old apartheid regime.

In 2019 De Jonge was given the Presidential Order of the Companions of OR Tambo (silver) for his excellent contribution to the fight for the liberation of the people of South Africa. He had turned it down earlier when it was to have been presented by President Zuma.

However, De Jonge, now 85, is suffering from terminal cancer. He says he has led a full life and has decided to have help in ending his life soon. Assisted suicide is granted in the Netherlands with strict conditions. He has written to friends and colleagues informing them of this. I will be among those who will miss him and celebrate his life and giggle at the extraordinary story he provided me with. DM/MC

Klaas de Jonge is awarded the Order of the Companions of OR Tambo in Silver by President Cyril Ramaphosa, 25 April 2019. (Photo: Twitter)

Pat Sidley has been a journalist since 1978 when she started on the Rand Daily Mail. When it closed she wrote for the Weekly Mail — now the Mail and Guardian — then on to a variety of local papers. She specialised in consumer affairs and health journalism. She worked for the Dutch news agency ANP and the British Medical Journal as a freelancer and now freelances for the International Bar Association as its southern African correspondent. She was involved in the journalists’ union (the Southern African Society of Journalists) in the earlier years and was its first female president.

Why did it take sooooo long to give this award? He was clearly an effective cadre.

Excellent article, Pat. Thank you for retelling the story in such detail. As you know, I was living in the Netherlands at the time and was a Dutch citizen so I was probably reading your reports in the Dutch press. I met Klaas after his release. Kathie Satchwell is a good friend. We were at Rhodes and we reconnected in Amsterdam when she was there to negotiate the release. I’m not sure if you have sent the story to her but I will send her the link.

Thank you for this. Kathy in fact helped me on the story. I happened so long ago that ageing memories can be flawed and I needed the help.

Does Pat Sidley not know that Klaas passed away this past weekend?